Hudson Valley

Hudson Valley | |

|---|---|

Region | |

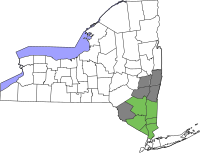

![Counties usually (green) and sometimes (gray) considered to be a part of the Hudson Valley region[a]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Map_of_New_York_highlighting_Hudson_Valley_2.svg/250px-Map_of_New_York_highlighting_Hudson_Valley_2.svg.png) Counties usually (green) and sometimes (gray) considered to be a part of the Hudson Valley region[a] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| Counties | Putnam, Rockland, Westchester, Dutchess, Orange, Sullivan, Ulster, Albany, Columbia, Greene, Rensselaer |

| Area | |

• Total | 7,228 sq mi (18,720 km2) |

| Population (2013) | |

• Total | 2,323,346 |

| • Density | 320/sq mi (120/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern Daylight Time) |

| Part of a series on |

| Regions of New York |

|---|

|

The Hudson Valley (also known as the Hudson River Valley) comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York. The region stretches from the Capital District including Albany and Troy south to Yonkers in Westchester County, bordering New York City.[1]

History

Pre-Columbian era

The Hudson Valley was inhabited by indigenous peoples long before European settlers arrived. The Lenape, Wappinger, and Mahican branches of the Algonquins lived along the river,[2] mostly in peace with the other groups.[2][3] The lower Hudson River was inhabited by the Lenape.[3] The Lenape people waited for the explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano onshore, traded with Henry Hudson, and sold the island of Manhattan.[3] Further north, the Wappingers lived from Manhattan Island up to Poughkeepsie. They lived a similar lifestyle to the Lenape, residing in various villages along the river. They traded with both the Lenape to the south and the Mahicans to the north.[2] The Mahicans lived in the northern valley from present-day Kingston to Lake Champlain,[3] with their capital located near present-day Albany.[2] The Algonquins in the region lived mainly in small clans and villages throughout the area. One major fortress was called Navish, which was located at Croton Point, overlooking the Hudson River. Other fortresses were located in various locations throughout the Hudson Highlands.[3]

Hudson River exploration

In 1497, John Cabot traveled along the coast and claimed the entire country for England; he is credited with the Old World's discovery of continental North America.[4] Between then and about 1609, exploration took place around New York Bay, but not into the Hudson Valley. In 1609, the Dutch East India Company financed English navigator Henry Hudson in his attempt to search for the Northwest Passage. During this attempt, Henry Hudson decided to sail his ship up the river that would later be named after him. As he continued up the river, its width expanded, into Haverstraw Bay, leading him to believe he had successfully reached the Northwest Passage. He also proceeded upstream as far as present-day Troy before concluding that no such strait existed there.[5]

Colonization

After Henry Hudson realized that the Hudson River was not the Northwest Passage, the Dutch began to examine the region for potential trading opportunities.[6] Dutch explorer and merchant Adriaen Block led voyages there between 1611 and 1614, which led the Dutch to determine that fur trade would be profitable in the region. As such, the Dutch established the colony of New Netherland.[7] The Dutch settled three major fur-trading outposts in the colony, along the river, south to north: New Amsterdam, Wiltwyck, and Fort Orange.[6] New Amsterdam later became known as New York City, Wiltwyck became Kingston, and Fort Orange became Albany.[6] In 1664, the British invaded New Netherland via the port of New Amsterdam.[6] New Amsterdam and New Netherland as a whole were surrendered to the British and renamed New York.[8]

Under British colonial rule, the Hudson Valley became an agricultural hub, with manors being developed on the east side of the river. At these manors, landlords rented out land to their tenants, letting them take a share of the crops grown while keeping and selling the rest of the crops.[9] Tenants were often kept at a subsistence level so that the landlord could minimize his costs. Landlords held immense political power in the colony due to driving such a large proportion of the agricultural output. Meanwhile, land west of Hudson River contained smaller landholdings with many small farmers living off the land. A large crop grown in the region was grain, which was largely shipped downriver to New York City, the colony's main seaport, for export back to Great Britain. In order to export the grain, colonial merchants were given monopolies to grind the grain into flour and export it.[9] Grain production was also at high levels in the Mohawk River Valley.[9]

Revolutionary War

The Hudson River was a key river during the Revolutionary War. The Hudson's connection to the Mohawk River allowed travelers to get to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River eventually. In addition, the river's close proximity to Lake George and Lake Champlain would allow the British navy to control the water route from Montreal to New York City.[10] In doing so, the British, under General John Burgoyne's strategy, would be able to cut off the patriot hub of New England (which is on the eastern side of the Hudson River) and focus on rallying the support of loyalists in the South and Mid-Atlantic regions. The British knew that total occupation of the colonies would be unfeasible, which is why this strategy was chosen.[11] As a result of the strategy, numerous battles were fought along the river, including several in the Hudson Valley.[12]

Industrial Revolution

In the early 19th century, popularized by the stories of Washington Irving, the Hudson Valley gained a reputation as a somewhat gothic region characterized by remnants of the early days of the Dutch colonization of New York (see "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow"). The area is also associated with the Hudson River School, a group of American Romantic painters who worked from about 1830 to 1870.[13]

Following the building of the Erie Canal, the area became an important industrial center. The canal opened the Hudson Valley and New York City to commerce with the Midwest and Great Lakes regions.[14] However, in the mid 20th century, many of the industrial towns went into decline.[15]

The first railroad in New York, the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, opened in 1831 between Albany and Schenectady on the Mohawk River, enabling passengers to bypass the slowest part of the Erie Canal.[16] The Hudson Valley proved attractive for railroads once technology progressed to the point where it was feasible to construct the required bridges over tributaries. The Troy and Greenbush Railroad was chartered in 1845 and opened that same year, running a short distance on the east side between Troy and Greenbush, now known as East Greenbush (east of Albany). The Hudson River Railroad was chartered the next year as a continuation of the Troy and Greenbush south to New York City, and was completed in 1851. In 1866, the Hudson River Bridge opened over the river between Greenbush and Albany, enabling through traffic between the Hudson River Railroad and the New York Central Railroad west to Buffalo. When the Poughkeepsie Bridge opened in 1889, it became the longest single-span bridge in the world.

The New York, West Shore and Buffalo Railway began at Weehawken Terminal and ran up the west shore of the Hudson as a competitor to the merged New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. Construction was slow and was finally completed in 1884; the New York Central purchased the line the next year.

During the Industrial Revolution, the Hudson River Valley became a major location for production. The river allowed for fast and easy transport of goods from the interior of the Northeast to the coast. Hundreds of factories were built around the Hudson, in towns including Poughkeepsie, Newburgh, Kingston, and Hudson. The North Tarrytown Assembly (later owned by General Motors), on the river in Sleepy Hollow, was a large and notable example. The river links to the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes, which allowed manufacturers in the Midwest, including automobile factories in Detroit, to use the river for transport.[17]: 71–2 With industrialization came new technologies, such as streamboats, for faster transport. In 1807, the North River Steamboat (later known as Clermont), became the first commercially successful steamboat.[18] It carried passengers between New York City and Albany along the Hudson River. At the end of the 19th century, the Hudson River region of New York State would become the world's largest brick manufacturing region, with 130 brickyards lining the shores of the Hudson River from Mechanicsville to Haverstraw and employing 8,000 people. At its peak, about 1 billion bricks a year were produced, with many being sent to New York City for use in its construction industry.[19]

Tourism became a major industry as early as 1810. With convenient steamboat connections in New York City and numerous attractive hotels in romantic settings, tourism became an important industry. Early guidebooks provided suggestions for travel itineraries. Middle-class people who read James Fenimore Cooper's novels or saw the paintings of the Hudson River School were especially attracted to the region.[20]

Geology and physiography

The Hudson River valley runs primarily north to south down the eastern edge of New York State, cutting through a series of rock types including Triassic sandstones and redbeds in the south and much more ancient Precambrian gneiss in the north (and east). In the Hudson Highlands, the river enters a fjord cut during previous ice ages. To the west lie the extensive Appalachian Highlands. In the Tappan Zee region, the west side of the river has high cliffs produced by an erosion-resistant diabase; the cliffs range from 400 to 800 feet (120 to 240 m) in height.[21]

The Hudson Valley is one physiographic section of the larger Ridge-and-Valley province, which in turn is part of the larger Appalachian physiographic division.[22] The northern portions of the Hudson Valley fall within the Eastern Great Lakes and Hudson Lowlands Ecoregion.

During the last ice age, the valley was filled by a large glacier that pushed south as far as Long Island. Near the end of the last ice age, the Great Lakes drained south down the Hudson River, from a large glacial lake called Lake Iroquois.[23] Lake Ontario is the remnant of that lake. Large sand deposits remain from where Lake Iroquois drained into the Hudson; these are now part of the Rome Sand Plains.

Due to its resemblance, the Hudson River often has been described as "America's Rhine". In 1939, the magazine Life described the river as such, comparing it to the 40-mile (64 km) stretch of the Rhine in Central and Western Europe.[24]

Major industries

Agriculture

The Hudson Valley has a long agricultural history and agriculture was its main industry when the region was first settled. Around the 1700s, tenant farming was highly practiced.[25] The farms' main products were grains (predominantly wheat), though hops, maple syrup, vegetables, dairy products, honey, wool, livestock, and tobacco were produced there. The region became the breadbasket of colonial America, given that the surrounding New England and Catskills areas were more mountainous and had rockier soils. In the late 1800s, most farms transitioned from tenant farming to being family-owned, with more incentive to improve the land. Grain production moved west to the Genesee Valley, and so Hudson Valley farms specialized, especially in viticulture, berries, and orchard cultivation. Agriculture began to decline in the 19th century, and rapidly declined in the 20th century.[26][27]

By the 1970s, the United States' culinary revolution began, and the Hudson Valley began to lead the farm-to-table movement, the local food movement, and sustainable agricultural practices. The fertile Black Dirt Region of the Wallkill and Schoharie valleys also began to be farmed. Dairy farms are predominant, though fruit, vegetable, poultry, meat, and maple syrup production are also common.[26] Orchard cultivation is common in Orange, Ulster, Dutchess, and Columbia counties.[27]

Winemaking

The Hudson Valley is one of the oldest winemaking and grape-growing regions in the United States, with its first vineyards planted in 1677 in current-day New Paltz.[26] The region has experienced a resurgence in winemaking in the 21st century. Many wineries are located in the Hudson Valley, offering wine-tasting and other tours.[28] Numerous wine festivals are held in the Hudson Valley, with themes often varying by season.[29] Rhinebeck is home to the Hudson Valley Wine & Food Fest, hosted at the Dutchess County Fairgrounds.[30]

The region has sunlight, moisture, chalky soil, and drainage conducive to grape growing, especially grapes used in Champagne.[27]

Tech Valley

Tech Valley is a marketing name for the eastern part of New York State, including the Hudson Valley and the Capital District.[31] Originating in 1998 to promote the greater Albany area as a high-tech competitor to regions such as Silicon Valley and Boston, it has since grown to represent the counties in New York between IBM's Westchester County plants in the south and the Canada–US border to the north. The area's high technology ecosystem is supported by technologically focused academic institutions including Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the State University of New York Polytechnic Institute.[32] Tech Valley encompasses 19 counties straddling both sides of the Adirondack Northway and the New York Thruway,[31] and with heavy state taxpayer subsidy, has experienced significant growth in the computer hardware industry, with great strides in the nanotechnology sector, digital electronics design, and water- and electricity-dependent integrated microchip circuit manufacturing,[33] involving companies including IBM in Armonk and its Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown, GlobalFoundries in Malta, and others.[32][34][35] Westchester County has developed a burgeoning biotechnology sector in the 21st century, with over US$1 billion in planned private investment as of 2016,[36] earning the county the nickname Biochester.[37]

Tourism

The Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area promotes historic, natural, and cultural sites in 11 counties.

Regions

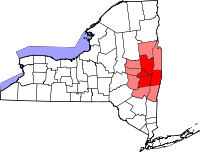

Lower Hudson (blue)[a]

The Hudson Valley is divided into three regions: Upper, Middle, and Lower. The following is a list of the counties within the Hudson Valley sorted by region.[38] The Lower Hudson Valley is typically considered part of the Downstate New York region due to its geographical and cultural proximity to New York City.

Lower Hudson

Upper Hudson/

Capital District

Infrastructure

Major interstates in the Hudson Valley include Interstate 87 (part of the New York State Thruway), a small section of Interstate 95 in Southeastern Westchester County, Interstate 287 serving Westchester and Rockland Counties, Interstate 84 serving Putnam, Dutchess, and Orange Counties, and Interstate 684 serving Westchester and Putnam Counties. Parkways in the region include the Bronx River Parkway, the Cross County Parkway, the Hutchinson River Parkway, the Sprain Brook Parkway, and the Saw Mill River Parkway serving solely Westchester County, the Taconic State Parkway serving Westchester, Putnam, Dutchess, and Columbia Counties, and the Palisades Interstate Parkway serving Rockland and a very small portion of southwestern Orange County. New York State Route 17 operates as a freeway in much of Orange County and will be designated Interstate 86 in the future.

Hudson River crossings in the Hudson Valley region from south to north include the Tappan Zee Bridge between South Nyack in Rockland County and Tarrytown in Westchester County, the Bear Mountain Bridge between Peekskill in Westchester County and Fort Montgomery in Orange County, the Newburgh-Beacon Bridge between Newburgh in Orange County and Beacon in Dutchess County, the Mid-Hudson Bridge between Poughkeepsie in Dutchess County and Highland in Ulster County, the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge between Rhinecliff in Dutchess County and Kingston in Ulster County, and the Rip Van Winkle Bridge between Hudson in Columbia County and Catskill in Greene County. The Walkway Over the Hudson is a pedestrian bridge which parallels the Mid-Hudson Bridge and was formerly a railroad bridge.

NY Waterway operates the Haverstraw-Ossining Ferry between Haverstraw in Rockland County and Ossining in Westchester County, as well as ferry service between Newburgh in Orange County and Beacon in Dutchess County. Intercity and commuter bus transit are provided by Rockland Coaches in Rockland County, Short Line in Orange and Rockland Counties, and Leprechaun Lines in Orange and Dutchess Counties. There are also several local bus providers, including the Bee-Line Bus System in Westchester County and Transport of Rockland in Rockland County.

The Hudson Valley is served by two airports with commercial airline service: Westchester County Airport (HPN) near White Plains and Stewart International Airport (SWF) near Newburgh.

Rail service

Commuter rail service in the region is provided by Metro-North Railroad (operated by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority). Metro-North operates three rail lines east of the Hudson River to Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan, from east to west they are the New Haven Line (serving southeast Westchester County), the Harlem Line (serving Central and Eastern Westchester, Putnam, and Dutchess Counties), and the Hudson Line (serving western Westchester, Putnam, and Dutchess Counties). West of the Hudson, New Jersey Transit operates two lines rail service under contract with Metro-North Railroad to Hoboken Terminal: the Pascack Valley Line (serving central Rockland County) and the Port Jervis Line (serving western Rockland County and Orange County).

Amtrak serves Yonkers, Croton-Harmon, Poughkeepsie, Rhinecliff-Kingston, and Hudson along the eastern shores of the Hudson River, as well as New Rochelle in southeastern Westchester County.

Sports

The Hudson Valley Renegades is a minor league baseball team affiliated with the New York Yankees.[39] The team is a member of the Mid-Atlantic League and plays at Dutchess Stadium in Fishkill. The New York Boulders of the independent Can-Am League play at Clover Stadium, in Pomona, NY.[40]

Kingston Stockade FC is a soccer team representing the Hudson Valley in the National Premier Soccer League (NPSL), a national semi-professional league at the fourth tier of the American Soccer Pyramid. They compete in the North Atlantic conference of the NPSL's Northeast region, and began their first season in May 2016.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Albany, Rensselaer, Greene, and Columbia counties are sometimes considered to be a part of the Capital District region, while Sullivan County is sometimes considered to be a part of the Catskill region.

References

Citations

- ^ "Mountains, Valleys and the Hudson River". Hudson Valley Tourism. 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Alfieri, J.; Berardis, A.; Smith, E.; Mackin, J.; Muller, W.; Lake, R.; Lehmkulh, P. (June 3, 1999). "The Lenapes: A study of Hudson Valley Indians" (PDF). Poughkeepsie, New York: Marist College. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Levine, David (June 24, 2016). "Hudson Valley's Tribal History". Hudson Valley Magazine. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ History of the County of Hudson, Charles H. Winfield, 1874, p. 1-2

- ^ Cleveland, Henry R. "Henry Hudson Explores the Hudson River". history-world.org. International World History Project. Archived from the original on January 12, 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d "Dutch Colonies". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ Varekamp, Johan Cornelis; Varekamp, Daphne Sasha (Spring–Summer 2006). "Adriaen Block, the discovery of Long Island Sound and the New Netherlands colony: what drove the course of history?" (PDF). Wrack Lines. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 23, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (August 25, 2014). "350 Years Ago, New Amsterdam Became New York. Don't Expect a Party". The New York Times. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c Leitner, Jonathan (2016). "Transitions in the Colonial Hudson Valley: Capitalist, Bulk Goods, and Braudelian". Journal of World-Systems Research. 22 (1): 214–246. doi:10.5195/jwsr.2016.615. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ Mansinne, Major Andrew Jr. "The West Point Chain and Hudson River Obstructions in the Revolutionary War" (PDF). desmondfishlibrary.org. Desmond Fish Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ Carroll, John Martin; Baxter, Colin F. (August 2006). The American Military Tradition: From Colonial Times to the Present (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 14–18. ISBN 9780742544284. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ Ayers, Edward L.; Gould, Lewis L.; Oshinky, David M.; Soderlund, Jean R. (2009). American Passage: A History of the United States (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. ISBN 9780547166292.

- ^ Dunwell, Francis F. (2008). The Hudson: America's river. Columbia University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-231-13641-9.

- ^ Stanne, Stephen P., et al. (1996). The Hudson: An Illustrated Guide to the Living River, p. 120. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2271-4.

- ^ Hirschl, Thomas A.; Heaton, Tim B. (1999). New York State in the 21st Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 126–128. ISBN 0-275-96339-X.

- ^ "The Hudson River Guide". www.offshoreblue.com. Blue Seas. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Harmon, Daniel E. (2004). "The Hudson River". Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 9781438125183. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ Hunter, Louis C. (1985). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730–1930, Vol. 2: Steam Power. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia.

- ^ Falkenstein, Michelle (June 28, 2022). "Brick collectors of the Hudson Valley". www.timesunion.com. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Richard H. Gassan, The Birth of American Tourism: New York, the Hudson Valley, and American Culture, 1790–1835 (2008)

- ^ Van Diver, B. B. (1985). Roadside Geology of New York. Mountain Press, Missoula. Pp. 59-63.

- ^ "Physiographic divisions of the conterminous U. S." U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved December 6, 2007.

- ^ Eyles, N. Ontario Rocks: Three Billion Years of Environmental Change. Markham, Ontario: Fitzhenry & Whiteside.

- ^ "The Hudson River: Autumn Peace Broods over America's Rhine". Life. October 2, 1939. p. 57. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- ^ Ellis, David M. (1944). "Land Tenure and Tenancy in the Hudson Valley, 1790-1860". Agricultural History. 18 (2): 75–82. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 3739598.

- ^ a b c "The Hudson Valley's Farm-to-Table Movement is Growing Faster Than Ever". June 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c Adams, Arthur G. (1996). The Hudson Through the Years. Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823216772.

- ^ "The Roots of American Wine since 1677". HUDSON VALLEY WINE COUNTRY.ORG. Archived from the original on October 11, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "The Roots of American Wine since 1677 - Calendar of Festivals and Events". HUDSON VALLEY WINE COUNTRY.ORG. Archived from the original on October 12, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ "Home". hudsonvalleywinefest.com.

- ^ a b "About Tech Valley". Tech Valley Chamber Coalition. Archived from the original on November 3, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Larry Rulison (July 10, 2015). "Made in Albany: IBM reveals breakthrough chip made at SUNY Poly". Albany Times-Union. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Keshia Clukey (June 27, 2014). "Better than advertised: Chip plant beats expectations". Albany Business Review. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ "Fab 8 Overview". GLOBALFOUNDRIES Inc. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Freeman Klopott; Xu Wang; Niamh Ring (September 27, 2011). "IBM, Intel Start $4.4 Billion in Chip Venture in New York". 2011 Bloomberg. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ John Jordan (January 2016). "$1.2 Billion Project Could Make Westchester a Biotech Destination". Hudson Gateway Association of Realtors. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ Steve Ditlea (May 7, 2015). "Westchester's Unexpected Powerhouse Position In the Biotech Industry - Four years after our initial look at Westchester's biotech industry, the sector has gone from fledgling to behemoth". Today Media. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

All around, there are signs of a Biochester bloom:

- ^ Silverman, B et al; Frommer's New York State Frommer's 2009, p196

- ^ "New York Yankees announce new Minor League affiliation structure". MLB.com. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ "Boulders' Home Park Renamed Clover Stadium". OurSports Central. January 25, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

Further reading

- Donaldson Eberlein, Harold; Van Dyke Hubbard, Cortlandt (1942). Historic houses of the Hudson valley. New York: Architectural Book Pub. Co. OCLC 3444265.

- Historic Hudson Valley (1991). Visions of Washington Irving: Selected Works From the Collections of Historic Hudson Valley. Tarrytown, New York: Historic Hudson Valley. ISBN 978-0-912882-99-4.

- Howat, John K. (1972). The Hudson River and Its Painters. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-38558-4.

- Jacobs, Jaap and L.H. Roper (eds.) (2014). The Worlds of the Seventeenth-Century Hudson Valley. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

- Levine, David (2020). The Hudson Valley: The First 250 Million Years. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot.

- Marks, Alfred H. (1973). Literature of the Mid Hudson Valley: A Preliminary Study. New Paltz, New York: Center for Continuing Education, State University College. OCLC 1171631.

- McMurry, James; Jones, Jeff (1974). The Catskill Witch and Other Tales of the Hudson Valley. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0105-0.

- Mylod, John (1969). Biography of a River: The People and Legends of the Hudson Valley. New York: Hawthorn Books. OCLC 33563.

- Scheltema, Gajus and Westerhuijs, Heleen (eds.),Exploring Historic Dutch New York. New York: Museum of the City of New York/Dover Publications, 2011.

- Talbott, Hudson (2009). River of Dreams: The Story of the Hudson River. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-399-24521-3.

- Vernon, Benjamin. The History of the Hudson River Valley (New York: Overlook, 2016. xiv, 625 pp.

- Wallkill Valley Publishing Association (1904). The Historic Wallkill and Hudson River Valleys. Walden, New York: Wallkill Valley Publishing Association. OCLC 13418978.

- Wharton, Edith (1929). Hudson River Bracketed. New York: D. Appleton & Company. OCLC 297188.

- Wilkinson Reynolds, Helen (1965). Dutch houses in the Hudson Valley before 1776. New York: Dover Publications. OCLC 513732.

External links

- Hudson Valley Directory at hudsonvalleydirectory.com

- Hudson River Valley Greenway at hudsongreenway.ny.gov

- Hudson River Valley Heritage: digital collection of historical materials, at hrvh.org

- Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area at hudsonrivervalley.com