Homo rhodesiensis

| Homo rhodesiensis Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

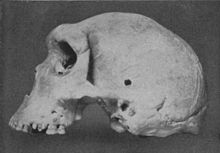

| Kabwe skull (1922 photograph) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Subtribe: | Hominina |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. rhodesiensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo rhodesiensis Woodward, 1921 | |

Homo rhodesiensis is the species name proposed by Arthur Smith Woodward (1921) to classify Kabwe 1 (the "Kabwe skull" or "Broken Hill skull", also "Rhodesian Man"), a Middle Stone Age fossil recovered from Broken Hill mine in Kabwe, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia).[1] In 2020, the skull was dated to 324,000 to 274,000 years ago. Other similar older specimens also exist.[2]

H. rhodesiensis is now widely considered a synonym of H. heidelbergensis.[3] Other designations such as Homo sapiens arcaicus[4] and Homo sapiens rhodesiensis[5] have also been proposed.

Fossils

A number of morphologically comparable fossil remains came to light in East Africa (Bodo, Ndutu, Eyasi, Ileret) and North Africa (Salé, Rabat, Dar-es-Soltane, Djbel Irhoud, Sidi Aberrahaman, Tighenif) during the 20th century.[6]

- Kabwe 1, also called the Broken Hill skull, or "Rhodesian Man", was assigned by Arthur Smith Woodward in 1921 as the type specimen for Homo rhodesiensis; most contemporary scientists forego the taxon "rhodesiensis" altogether and assign it to Homo heidelbergensis.[7] The cranium was discovered in Broken Hill lead mine in Mutwe Wa Nsofu Area of Northern Rhodesia (now Kabwe, Zambia) on June 17, 1921[8] by two miners. In addition to the cranium, an upper jaw from another individual, a sacrum, a tibia, and two femur fragments were also found.

- Bodo cranium: The 600,000 year old[9] fossil was found in 1976 by members of an expedition led by Jon Kalb at Bodo D'ar in the Awash River valley of Ethiopia.[10] Although the skull is most similar to those of Kabwe, Woodward's nomenclature was discontinued and its discoverers attributed it to H. heidelbergensis.[11] It has features that represent a transition between Homo ergaster/erectus and Homo sapiens.[12]

- Ndutu cranium,[13] "the hominid from Lake Ndutu" in northern Tanzania, around 600–500,000 years old[14] or 400,000 years old. In 1976 R. J. Clarke classified it as Homo erectus and it has generally been viewed that way, although points of similarity to H. sapiens have also been recognized. After comparative studies with similar finds in Africa allocation to an African subspecies of H. sapiens was considered most appropriate by Phillip Rightmire.[15] An indirect cranial capacity estimate suggests 1100 ml. Its supratoral sulcus morphology and the presence of protuberance as suggested by Rightmire "give the Nudutu occiput an appearance which is also unlike that of Homo erectus". And in a 1989 publication Clarke concluded: "It is assigned to archaic Homo sapiens on the basis of its expanded parietal and occipital regions of the brain".[16] But Stinger (1986) pointed out that a thickened iliac pillar is typical for Homo erectus.[17] In 2016, Chris Stringer classified the cranium as belonging to Homo heidelbergensis/Homo rhodesiensis (a species considered to be intermediate between Homo erectus and Homo sapiens) rather than as early H. sapiens, but considers it to display a "more sapiens-like zygomaxillary morphology" than certain other examples of Homo rhodesiensis.[18]

- The Saldanha cranium found in 1953 in South Africa, and estimated at around 500,000 years old, was subject to at least three taxonomic revisions from 1955 to 1996.[19]

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bodo cranium

The Bodo cranium[20] is a fossil of an extinct type of hominin species. It was found by members of an expedition led by Jon Kalb in 1976.[21] The Rift Valley Research Mission conducted a number of surveys that led to the findings of Acheulean tools and animal fossils, as well as the Bodo Cranium.[22] The initial discovery was by Alemayhew Asfaw and Charles Smart, who found a lower face. Two weeks later, Paul Whitehead and Craig Wood found the upper portion of the face. Pieces of the cranium were discovered along the surface of one of the dry branches of the Awash River in Ethiopia.[20] The cranium, artifacts, and other animal fossils were found over a relatively large area of medium sand, and only a few of the tools were found near the cranium.[23][24] The skull is 600,000 years old.[25]

Observation

This specimen has an unusually large cranial capacity for its age that is estimated at around 1250 cc (in the range between ~1,200–1,325 cc) within the (lower) range of modern Homo sapiens.[26] The cranium includes the face, much of the frontal bone, parts of the midvault and the base anterior to the foramen magnum. The cranial length, width and height are 21 cm (8.3 in), 15.87 cm (6.2 in) and 19.05 cm (7.5 in) respectively. Researchers have suggested that Bodo butchered animals because Acheulean hand axes and cleavers, along with animal bones, were found at the site. Cuts on the Bodo cranium show the earliest evidence of removal of flesh immediately after the death of an individual using a stone tool.[23] The findings of symmetrical cut marks with specific patterns and directionality on the cranium serve as strong evidence that de-fleshing was done purposefully for mortuary practices and represents the earliest evidence of non-utilitarian mortuary practices.[23][27] The cut marks were located "laterally among the maxilla" causing speculation among researchers that the specific reason for de-fleshing was to remove the mandible.[28]

Morphology

The front of the Bodo cranium is very broad and supports large supraorbital structures. The supraorbital torus projects and is heavily constructed, especially in the central parts of the cranium. The Glabella is rounded and projects strongly. Like Homo erectus, the braincase is low and archaic in appearance. The vault bones are also thick like Homo erectus specimens. Due to the large cranial capacity, there is a wider midvault which includes signs of parietal bossing as well as a high contour of the temporal squama. The parietal length can’t be accurately determined because that section of the specimen is incomplete. Though the mastoid is missing, insights regarding the specimen can be determined using fragments from the individual collected at the scene in 1981. The cranium’s parietal walls expand relative to the bitemporal width in a way that is characteristic of modern humans. The squamosal suture has a high arch which is present in modern human craniums as well.[29]

Evolutionary significance

The cranium has an unusual appearance, which has led to debates over its taxonomy. It displays both primitive and derived features, such as a cranial capacity more similar to modern humans and a projecting supraorbital torus more like Homo erectus.[20][30][31] Bodo and other Mid-Pleistocene hominin fossils appear to represent a lineage between Homo erectus and anatomically modern humans, although its exact location in the human evolutionary tree is still uncertain.[32][33] Due to the similarities to both Homo erectus and modern humans, it has been postulated that the Bodo cranium, as well as other members of Homo heidelbergensis were part of a group of hominins that evolved distinct from Homo erectus early in the Middle Pleistocene. Despite the similarities, there is still a question of where exactly Homo heidelbergensis evolved. The increased encephalization seen in fossils like the Bodo cranium is thought to have been a driving force in the speciation of anatomically modern humans.[34][35]

Similarities between the Bodo cranium and Kabwe cranium

Both the Bodo cranium and the Kabwe cranium share a number of similarities. Both have cranial capacities similar to, but on the low end of the range of modern humans (1250cc vs 1230cc). Both craniums have a very large supraorbital torus. These two features together suggest that they are a link between Homo erectus and Homo sapiens.[36] The morphology and the taxonomy are most similar to other specimens of type Homo heidelbergensis.[37] Both the Bodo and Kabwe specimens can be described as archaic because they retain certain features in common with Homo erectus. However, both exhibit important differences from Homo erectus in their anatomy, such as the contour of their parietals, the shape of their temporal bones, the cranial base, and the morphology of their nose and palate. While there are many similarities, there are a few differences between the specimens, including the entire brow of the Bodo cranium, particularly the lateral segments, which are less thick than the Kabwe specimen.[29]

"Homo bodoensis"

In 2021, Canadian anthropologist Mirjana Roksandic and colleagues recommended the complete dissolution of H. heidelbergensis and "H. rhodesiensis", as the name rhodesiensis honours English diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes who disenfranchised the black population in southern Africa. They classified all European H. heidelbergensis as H. neanderthalensis, and synonymised H. rhodesiensis with a new species they named "H. bodoensis" which includes all African specimens, and potentially some from the Levant and the Balkans which have no Neanderthal-derived traits (namely Ceprano, Mala Balanica, HaZore'a and Nadaouiyeh Aïn Askar). "H. bodoensis" is supposed to represent the immediate ancestor of modern humans, but does not include the LCA of modern humans and Neanderthals. They suggested the confusing morphology of the Middle Pleistocene was caused by periodic "H. bodoensis" migration events into Europe following population collapses after glacial cycles, interbreeding with surviving indigenous populations.[38] Their taxonomic recommendations were rejected by Stringer and others as they failed to explain how exactly their proposals would resolve anything, in addition to violating nomenclatural rules.[39][40]

See also

References

- ^ "GBIF 787018738 Fossil of Homo rhodesiensis Woodward, 1921". GBIF org. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Grün, Rainer; Pike, Alistair; McDermott, Frank; Eggins, Stephen; Mortimer, Graham; Aubert, Maxime; Kinsley, Lesley; Joannes-Boyau, Renaud; Rumsey, Michael; Denys, Christiane; Brink, James; Clark, Tara; Stringer, Chris (2020-04-01). "Dating the skull from Broken Hill, Zambia, and its position in human evolution" (PDF). Nature. 580 (7803): 372–375. Bibcode:2020Natur.580..372G. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2165-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32296179. S2CID 214736650.

- ^ Ni, Xijun; Ji, Qiang; Wu, Wensheng; Shao, Qingfeng; Ji, Yannan; Zhang, Chi; Liang, Lei; Ge, Junyi; Guo, Zhen; Li, Jinhua; Li, Qiang; Grün, Rainer; Stringer, Chris (2021-08-28). "Massive cranium from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage". The Innovation. 2 (3): 100130. Bibcode:2021Innov...200130N. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130. ISSN 2666-6758. PMC 8454562. PMID 34557770.

- ^ H. James Birx (10 June 2010). 21st Century Anthropology: A Reference Handbook. SAGE Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4522-6630-5.

- ^ Bernard Wood (31 March 2011). Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 761–762. ISBN 978-1-4443-4247-5.

- ^ "The evolution and development of cranial form in Homo" (PDF). Department of Anthropology, Harvard University. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Hublin, J.-J. (2013), "The Middle Pleistocene Record. On the Origin of Neandertals, Modern Humans and Others" in: R. David Begun (ed.), A Companion to Paleoanthropology, John Wiley, pp. 517–537 (p. 523).

- ^ "Zambia resolute on recovering Broken Hill Man from Britain – Zambia Daily Mail". Daily-mail.co.zm. 2015-01-10. Archived from the original on 2018-03-01. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ^ "Bodo – Paleoanthropology site information". Fossilized org. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ "Bodo Skull and Jaw". Skulls Unlimited. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ "Bodo fossil". Britannica Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ "Meet Bodo and Herto There is some discussion around the species assigned to Bodo". Nutcracker Man. April 7, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Rightmire, G. Philip (2005). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early Homo sapiens in Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (2): 245–254. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925.

- ^ Mturi, A A (August 1976). "New hominid from Lake Ndutu, Tanzania". Nature 262: 484–485.

- ^ Rightmire GP (June 3, 1983). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early Homo sapiens in Africa". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 61 (2): 245–54. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925.

- ^ "The Ndutu cranium and the origin of Homo sapiens – R. J. Clarke" (PDF). American Museum of Natural History. November 27, 1989. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ The Evolution of Homo erectus: Comparative Anatomical Studies of an Extinct Human Species By G. Philip Rightmire Published by Cambridge University Press, 1993 ISBN 0-521-44998-7, ISBN 978-0-521-44998-4 [1]

- ^ Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. PMC 4920294. PMID 27298468.

- ^ Wood, Bernard (31 March 2011). Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444342475. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c Rightmire, Philip G. (1996-07-01). "The human cranium from Bodo, Ethiopia: evidence for speciation in the Middle Pleistocene?". Journal of Human Evolution. 31 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0046. ISSN 0047-2484.

- ^ "Bodo Skull and Jaw". Skulls Unlimited. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Conroy, Glenn C.; Weber, Gerhard W.; Seidler, Horst; Recheis, Wolfgang; Zur Nedden, Dieter; Haile Mariam, Jara (2000). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 113 (1): 111–118. doi:10.1002/1096-8644(200009)113:1<111::aid-ajpa10>3.0.co;2-x. PMID 10954624.

- ^ a b c White, Tim D. (April 1986). "Cut marks on the Bodo cranium: A case of prehistoric defleshing". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 69 (4): 503–509. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330690410. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 3087212.

- ^ Kalb, Jon E.; Wood, Craig B.; Smart, Charles; Oswald, Elizabeth B.; Mabrete, Assefa; Tebedge, Sleshi; Whitehead, Paul (1980-01-01). "Preliminary geology and palaeontology of the Bodo D'ar hominid Site, Afar, Ethiopia". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 30: 107–120. Bibcode:1980PPP....30..107K. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(80)90052-8. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ "Bodo". Humanorigins.si.edu. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Milner, Richard. "Cranial Capacity." The Encyclopedia of Evolution: Humanity's Search For Its Origins. New York: Holt, 1990: 98. "Living humans have a cranial capacity ranging from about 950 cc to 1800 cc, with the average about 1400 cc."

- ^ Tarlow, Sarah; Stutz, Liv Nilsson (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0199569069.

- ^ Pickering, Travis Rayne; White, Tim D.; Toth, Nicholas (2000). "Brief communication: Cutmarks on a Plio-Pleistocene hominid from Sterkfontein, South Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 111 (4): 579–584. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8644(200004)111:4<579::aid-ajpa12>3.0.co;2-y. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 10727975.

- ^ a b Rightmire, Philip G. (July 1996). "The human cranium from Bodo, Ethiopia: evidence for speciation in the Middle Pleistocene?". Journal of Human Evolution. 31 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0046. ISSN 0047-2484.

- ^ Rightmire, G. Philip (2001-01-01). "Patterns of hominid evolution and dispersal in the Middle Pleistocene". Quaternary International. 75 (1): 77–84. Bibcode:2001QuInt..75...77R. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(00)00079-3. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Bräuer, Günter (2008). "The origin of modern anatomy: By speciation or intraspecific evolution?". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 17 (1): 22–37. doi:10.1002/evan.20157. ISSN 1520-6505. S2CID 53328127.

- ^ Rightmire, G. Philip (2013-09-01). "Homo erectus and Middle Pleistocene hominins: Brain size, skull form, and species recognition". Journal of Human Evolution. 65 (3): 223–252. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.04.008. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 23850294.

- ^ Krovitz, Gail; McBratney, Brandeis M.; Lieberman, Daniel E. (2002-02-05). "The evolution and development of cranial form in Homo sapiens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (3): 1134–1139. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.1134L. doi:10.1073/pnas.022440799. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 122156. PMID 11805284.

- ^ Rightmire, G. Philip (January 2012). "The evolution of cranial form in mid-Pleistocene Homo". South African Journal of Science. 108 (3–4): 68–77. doi:10.4102/sajs.v108i3/4.719. ISSN 0038-2353.

- ^ Conroy, Glenn C.; Weber, Gerhard W.; Seidler, Horst; Recheis, Wolfgang; Nedden, Dieter Zur; Mariam, Jara Haile (2000). "Endocranial capacity of the Bodo cranium determined from three-dimensional computed tomography". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 113 (1): 111–118. doi:10.1002/1096-8644(200009)113:1<111::aid-ajpa10>3.0.co;2-x. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 10954624.

- ^ Balzeau, A.; Buck, Laura; Albessard, L.; Becam, G.; Grimmaud-Herve, D.; Rae, T. C.; Stringer, C. B. (2017-12-08). "The internal cranial anatomy of the Middle Pleistocene Broken Hill 1 cranium". doi:10.17863/CAM.16919.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rightmire, Philip G. (1996-07-01). "The human cranium from Bodo, Ethiopia: evidence for speciation in the Middle Pleistocene?". Journal of Human Evolution. 31 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0046. ISSN 0047-2484.

- ^ Roksandic, M.; Radović, P.; Wu, X.-J.; Bae, C.J. (2021). "Resolving the "muddle in the middle": The case for Homo bodoensis sp. nov". Evolutionary Anthropology. 31 (1): 20–29. doi:10.1002/evan.21929. PMC 9297855. PMID 34710249.

- ^ Delson, E.; Stringer, C. (2022). "The naming of Homo bodoensis by Roksandic and colleagues does not resolve issues surrounding Middle Pleistocene human evolution". Evolutionary Anthropology. 17 (1): 233–236. doi:10.1002/evan.21950. PMID 35758557. S2CID 250070886.

- ^ Sarmiento, E.; Pickford, M. (2022). "Muddying the muddle in the middle even more". Evolutionary Anthropology. 31 (5): 237–239. doi:10.1002/evan.21952. PMID 35758530. S2CID 250071605.

Literature

- Woodward, Arthur Smith (1921). "A New Cave Man from Rhodesia, South Africa". Nature. 108 (2716): 371–372. Bibcode:1921Natur.108..371W. doi:10.1038/108371a0.

- Singer Robert R. and J. Wymer (1968). "Archaeological Investigation at the Saldanha Skull Site in South Africa". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 23 (3). The South African Archaeological Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 91: 63–73. doi:10.2307/3888485. JSTOR 3888485.

- Murrill, Rupert I. (1975). "A comparison of the Rhodesian and Petralona upper jaws in relation to other Pleistocene hominids". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie. 66 (2): 176–187. doi:10.1127/zma/66/1975/176. PMID 806185. S2CID 3097781..

- Murrill, Rupert Ivan (1981). Ed. Charles C. Thomas (ed.). Petralona Man. A Descriptive and Comparative Study, with New Information on Rhodesian Man. Springfield, Illinois: Thomas. ISBN 0-398-04550-X.

- Rightmire, G. Philip (2005). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early Homo sapiens in Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (2): 245–254. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925..

- Asfaw, Berhane (2005). "A new hominid parietal from Bodo, middle Awash Valley, Ethiopia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (3): 367–371. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610311. PMID 6412559..

External links

Media related to Homo rhodesiensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Homo rhodesiensis at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Homo rhodesiensis at Wikispecies

Data related to Homo rhodesiensis at Wikispecies- "Kabwe 1". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origin Program. January 1921. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).