History of al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda has five distinct phases in its development: its beginnings in the late 1980s, a "wilderness" period in 1990–1996, its "heyday" in 1996–2001, a network period from 2001 to 2005, and a period of fragmentation from 2005 to 2009.[1]

Jihad in Afghanistan

The origins of al-Qaeda can be traced to the Soviet War in Afghanistan (December 1979 – February 1989).[2] The United States viewed the conflict in Afghanistan in terms of the Cold War, with Marxists on one side and the native Afghan mujahideen on the other. This view led to a CIA program called Operation Cyclone, which channeled funds through Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency to the Afghan Mujahideen.[3] The US government provided substantial financial support to the Afghan Islamic militants. Aid to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, an Afghan mujahideen leader and founder of the Hezb-e Islami, amounted to more than $600 million. In addition to American aid, Hekmatyar was the recipient of Saudi aid.[4] In the early 1990s, after the US had withdrawn support, Hekmatyar "worked closely" with bin Laden.[5]

At the same time, a growing number of Arab mujahideen joined the jihad against the Afghan Marxist regime, which was facilitated by international Muslim organizations, particularly the Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), also known as the "Services Bureau". Muslim Brotherhood networks affiliated with the Egyptian Islamist Kamal al-Sananiri (d. 1981) played the major role in raising finances and Arab recruits for the Afghan Mujahidin. These networks included Mujahidin groups affiliated with Afghan commander Abd al-Rasul Sayyaf and Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, Palestinian Islamist scholar and major figure in the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood. Following the detention and death of Sananiri in an Egyptian security prison in 1981, Abdullah Azzam became the chief arbitrator between the Afghan Arabs and Afghan mujahideen.[6]

As part of providing weaponry and supplies for the cause of Afghan Jihad, Usama bin Laden was sent to Pakistan as a Muslim Brotherhood representative to the Islamist organisation Jamaat-e-Islami. While in Peshawar, bin Laden met Abdullah Azzam and the two of them jointly established the Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK) in 1984; with objective of raising funds and recruits for Afghan Jihad across the world. MAK organized guest houses in Peshawar, near the Afghan border, and gathered supplies for the construction of paramilitary training camps to prepare foreign recruits for the Afghan war front. MAK was funded by the Saudi government as well as by individual Muslims including Saudi businessmen.[7][8][page needed] Bin Laden also became a major financier of the mujahideen, spending his own money and using his connections to influence public opinion about the war.[9] Many disgruntled members of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood like Abu Mussab al-Suri also began joining these MAK networks; following the crushing of Islamic revolt in Syria in 1982.[10]

From 1986, MAK began to set up a network of recruiting offices in the US, the hub of which was the Al Kifah Refugee Center at the Farouq Mosque on Brooklyn's Atlantic Avenue. Among notable figures at the Brooklyn center were "double agent" Ali Mohamed, whom FBI special agent Jack Cloonan called "bin Laden's first trainer",[11] and "Blind Sheikh" Omar Abdel-Rahman, a leading recruiter of mujahideen for Afghanistan. Azzam and bin Laden began to establish camps in Afghanistan in 1987.[12]

MAK and foreign mujahideen volunteers, or "Afghan Arabs", did not play a major role in the war. While over 250,000 Afghan mujahideen fought the Soviets and the communist Afghan government, it is estimated that there were never more than two thousand foreign mujahideen on the field at any one time.[13] Nonetheless, foreign mujahideen volunteers came from 43 countries, and the total number who participated in the Afghan movement between 1982 and 1992 is reported to have been 35,000.[14] Bin Laden played a central role in organizing training camps for the foreign Muslim volunteers.[15][16]

The Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989. Mohammad Najibullah's Communist Afghan government lasted for three more years, before it was overrun by elements of the mujahideen.

Alleged CIA contacts with al-Qaeda

Experts debate the notion that the al-Qaeda attacks were an indirect consequence of the American CIA's Operation Cyclone program to help the Afghan mujahideen. Robin Cook, British Foreign Secretary from 1997 to 2001, wrote in 2005 that al-Qaeda and bin Laden were "a product of a monumental miscalculation by western security agencies", and claimed that "Al-Qaida, literally 'the database', was originally the computer file of the thousands of mujahideen who were recruited and trained with help from the CIA to defeat the Russians."[17]

Munir Akram, Permanent Representative of Pakistan to the United Nations from 2002 to 2008, wrote in a letter published in The New York Times on January 19, 2008:

The strategy to support the Afghans against Soviet military intervention was evolved by several intelligence agencies, including the C.I.A. and Inter-Services Intelligence, or ISI. After the Soviet withdrawal, the Western powers walked away from the region, leaving behind 40,000 militants imported from several countries to wage the anti-Soviet jihad. Pakistan was left to face the blowback of extremism, drugs and guns.[18]

CNN journalist Peter Bergen, Pakistani ISI Brigadier Mohammad Yousaf, and CIA operatives involved in the Afghan program, such as Vincent Cannistraro,[19] deny that the CIA or other American officials had contact with the foreign mujahideen or bin Laden, or that they armed, trained, coached or indoctrinated them. In his 2004 book Ghost Wars, Steve Coll writes that the CIA had contemplated providing direct support to the foreign mujahideen, but that the idea never moved beyond discussions.[20]

Bergen and others[who else?] argue that there was no need to recruit foreigners unfamiliar with the local language, customs or lay of the land since there were a quarter of a million local Afghans willing to fight.[20][failed verification] Bergen further argues that foreign mujahideen had no need for American funds since they received several million dollars per year from internal sources. Lastly, he argues that Americans could not have trained the foreign mujahideen because Pakistani officials would not allow more than a handful of them to operate in Pakistan and none in Afghanistan, and the Afghan Arabs were almost invariably militant Islamists reflexively hostile to Westerners whether or not the Westerners were helping the Muslim Afghans.

According to Bergen, who conducted the first television interview with bin Laden in 1997: the idea that "the CIA funded bin Laden or trained bin Laden ... [is] a folk myth. There's no evidence of this ... Bin Laden had his own money, he was anti-American and he was operating secretly and independently ... The real story here is the CIA didn't really have a clue about who this guy was until 1996 when they set up a unit to really start tracking him."[21]

Jason Burke also wrote:

Some of the $500 million the CIA poured into Afghanistan reached [Al-Zawahiri's] group. Al-Zawahiri has become a close aide of bin Laden ... Bin Laden was only loosely connected with the [Hezb-i-Islami faction of the mujahideen led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar], serving under another Hezb-i-Islami commander known as Engineer Machmud. However, bin Laden's Office of Services, set up to recruit overseas for the war, received some US cash.[22]

Expanding operations

Toward the end of the Soviet military mission in Afghanistan, some foreign mujahideen wanted to expand their operations to include Islamist struggles in other parts of the world, such as Palestine and Kashmir. A number of overlapping and interrelated organizations were formed, to further those aspirations. One of these was the organization that would eventually be called Al-Qaeda.

Research suggests[clarification needed] that al-Qaeda was formed on August 11, 1988, when a meeting in Afghanistan between leaders of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, Abdullah Azzam, and bin Laden took place.[23] The network was founded in 1988[24] by Osama bin Laden, Abdullah Azzam,[25] and other Arab volunteers during the Soviet–Afghan War.[2] An agreement was reached to link bin Laden's money with the expertise of the Islamic Jihad organization and take up the jihadist cause elsewhere after the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan.[26] After fighting the "holy" war, the group aimed to expand such operations to other parts of the world, setting up bases in parts of Africa, the Arab world and elsewhere,[27] carrying out many attacks on people whom it considers kāfir.[28]

Notes indicate[clarification needed] Al-Qaeda was a formal group by August 20, 1988. A list of requirements for membership itemized the following: listening ability, good manners, obedience, and making a pledge (Bay'at) to follow one's superiors.[29] In his memoir, bin Laden's former bodyguard, Nasser al-Bahri, gives the only publicly available description of the ritual of giving bay'at when he swore his allegiance to the Al-Qaeda chief.[30] According to Wright, the group's real name was not used in public pronouncements because "its existence was still a closely held secret."[31]

After Azzam was assassinated in 1989 and MAK broke up, significant numbers of MAK followers joined bin Laden's new organization.[32]

In November 1989, Ali Mohamed, a former special forces sergeant stationed at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, left military service and moved to California. He traveled to Afghanistan and Pakistan and became "deeply involved with bin Laden's plans."[33] In 1991, Ali Mohammed is said to have helped orchestrate bin Laden's relocation to Sudan.[27]

Gulf War and the start of US enmity

When the American troops entered Saudi Arabia [after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait], the land of the two holy places [ Mecca and Medina ], there was strong protest from the ulema [religious authorities] and from students of the Shariah law all over the country against the interference of American troops..This big mistake by the Saudi regime of inviting the American troops revealed their deception. They had given their support to nations that were fighting against Muslims. They [the Saudis] helped Yemen Communists against the southern Yemeni Muslims and helped Arafat’s regime fight against Hamas. After it had insulted and jailed the ulema…the Saudi regime lost its legitimacy.

Following the Soviet Union's withdrawal from Afghanistan in February 1989, bin Laden returned to Saudi Arabia. Thrilled by his successes in Afghan jihad, bin Laden turned his anti-communist posture towards South Yemen and requested Saudi authorities to lead an armed Jihad against communist South Yemen. However, the Saudi Intelligence chief Turki bin Faisal rebuffed bin Laden's offers, insisting on waiting for the collapse of the unstable communist regime. This led to the first major dispute of bin Laden with the Saudi monarchy.[34][35][36]

Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 had put the Kingdom and its ruling House of Saud at risk. The world's most valuable oil fields were within striking distance of Iraqi forces in Kuwait, and Saddam's call to Pan-Arabism could potentially rally internal dissent. In the face of a seemingly massive Iraqi military presence, Saudi Arabia's own forces were outnumbered. Bin Laden offered the services of his mujahideen to King Fahd to protect Saudi Arabia from the Iraqi army. The Saudi monarch refused bin Laden's offer, opting instead to allow US and allied forces to deploy troops into Saudi territory.[37] The arrival of American troops to the Kingdom in August 1990 was heavily condemned by bin Laden.[38]

The deployment angered bin Laden, as he believed the presence of foreign troops in the "land of the two mosques" (Mecca and Medina) profaned sacred soil. King Fahd's refusal of bin Laden's offer to train the Mujahidin; instead giving permission for American soldiers to enter Saudi territory in order to repel Saddam Hussein's forces would greatly anger bin Laden. The entry of American troops into Saudi Arabia was denounced by bin Laden as a "Crusader attack on Islam" that defiled the sacred lands of Islam. He asserted that the Arabian Peninsula has been "occupied" by foreign invaders and excommunicated the Saudi regime due to its complicity with United States. After relentless criticism of the Saudi government for harboring American troops and rejecting their legitimacy, he was banished in 1991 and forced to live in exile in Sudan. Bin Laden also vehemently denounced the elder Wahhabi scholarship; most notably Grand Mufti Abd al-Azeez Ibn Baz, accusing him of partnering with infidel forces due to his fatwa that permitted the entry of US troops.[39][38]

Sudan

From around 1992 to 1996, Al-Qaeda and bin Laden based themselves in Sudan at the invitation of Islamist theoretician Hassan al-Turabi. The move followed an Islamist coup d'état in Sudan, led by Colonel Omar al-Bashir, who professed a commitment to reordering Muslim political values. During this time, bin Laden assisted the Sudanese government, bought or set up various business enterprises, and established training camps.

A key turning point for bin Laden occurred in 1993 when Saudi Arabia gave support for the Oslo Accords, which set a path for peace between Israel and Palestinians.[40] Due to bin Laden's continuous verbal assault on King Fahd of Saudi Arabia, Fahd sent an emissary to Sudan on March 5, 1994, demanding bin Laden's passport. Bin Laden's Saudi citizenship was also revoked. His family was persuaded to cut off his stipend, $7 million a year, and his Saudi assets were frozen.[41][42] His family publicly disowned him. There is controversy as to what extent bin Laden continued to garner support from members afterwards.[43]

In 1993, a young schoolgirl was killed in an unsuccessful attempt on the life of the Egyptian prime minister, Atef Sedki. Egyptian public opinion turned against Islamist bombings, and the police arrested 280 of al-Jihad's members and executed 6.[44] In a document published in June 1994, bin Laden accused Saudi Arabia of propping up the ex-communist Yemeni Socialist Party, the ruling party of Marxist South Yemen, by using it as a separatist force in Yemen to "forestall Islamic unity and keep the people of the region cowering".[45] In June 1995, an attempt to assassinate Egyptian president Mubarak led to the expulsion of Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ), and in May 1996, of bin Laden from Sudan.[citation needed]

According to Pakistani-American businessman Mansoor Ijaz, the Sudanese government offered the Clinton Administration numerous opportunities to arrest bin Laden. Ijaz's claims appeared in numerous op-ed pieces, including one in the Los Angeles Times[46] and one in The Washington Post co-written with former Ambassador to Sudan Timothy M. Carney.[47] Similar allegations have been made by Vanity Fair contributing editor David Rose,[48] and Richard Miniter, author of Losing bin Laden, in a November 2003 interview with World.[49]

Several sources dispute Ijaz's claim, including the 9/11 Commission, which concluded in part:

Sudan's minister of defense, Fatih Erwa, has claimed that Sudan offered to hand Bin Ladin over to the US. The Commission has found no credible evidence that this was so. Ambassador Carney had instructions only to push the Sudanese to expel Bin Ladin. Ambassador Carney had no legal basis to ask for more from the Sudanese since, at the time, there was no indictment out-standing.[50]

Refuge in Afghanistan

After the fall of the Afghan communist regime in 1992, Afghanistan was effectively ungoverned for four years and plagued by constant infighting between various mujahideen groups.[citation needed] This situation allowed the Taliban to organize. The Taliban also garnered support from graduates of Islamic schools, which are called madrassa. According to Ahmed Rashid, five leaders of the Taliban were graduates of Darul Uloom Haqqania, a madrassa in the small town of Akora Khattak.[51] The town is situated near Peshawar in Pakistan, but the school is largely attended by Afghan refugees.[51] This institution reflected Salafi beliefs in its teachings, and much of its funding came from private donations from wealthy Arabs. Four of the Taliban's leaders attended a similarly funded and influenced madrassa in Kandahar. Bin Laden's contacts were laundering donations to these schools, and Islamic banks were used to transfer money to an "array" of charities which served as front groups for Al-Qaeda.[52]

Many of the mujahideen who later joined the Taliban fought alongside Afghan warlord Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi's Harkat i Inqilabi group at the time of the Russian invasion. This group also enjoyed the loyalty of most Afghan Arab fighters.

The continuing lawlessness enabled the growing and well-disciplined Taliban to expand their control over territory in Afghanistan, and it came to establish an enclave which it called the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. In 1994, it captured the regional center of Kandahar, and after making rapid territorial gains thereafter, the Taliban captured the capital city Kabul in September 1996.

In 1996, Taliban-controlled Afghanistan provided a perfect staging ground for Al-Qaeda.[53] While not officially working together, Al-Qaeda enjoyed the Taliban's protection and supported the regime in such a strong symbiotic relationship that many Western observers dubbed the Taliban's Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan as, "the world's first terrorist-sponsored state."[54] However, at this time, only Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates recognized the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. In 1996, Osama bin Laden officially issued the "Declaration of Struggle against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Mosques" which called upon Muslims all over the world to take up arms against American soldiers. In an interview with the English journalist Robert Fisk; Bin Laden criticised American imperialism and its support for Zionism as the biggest sources of tyranny in the Arab world. He vehemently denounced the US-allied Gulf monarchies; especially the Saudi government for westernising the country, removing Islamic laws and hosting American, British and French troops. Bin Laden asserted that he planned to foment an armed rebellion to overthrow the Saudi regime with the help of his Mujahidin soldiers and establish an Islamic emirate in Arabian Peninsula that properly upholds Sharia (Islamic law).[55][56] Upon questioned whether he sought to launch a war against the Western world; bin Laden replied:

"It is not a declaration of war – it's a real description of the situation. This doesn't mean declaring war against the West and Western people – but against the American regime which is against every Muslim."[55][56]

In response to the 1998 United States embassy bombings, an Al-Qaeda base in Khost Province was attacked by the United States during Operation Infinite Reach.

While in Afghanistan, the Taliban government tasked Al-Qaeda with the training of Brigade 055, an elite element of the Taliban's army. The Brigade mostly consisted of foreign fighters, veterans from the Soviet Invasion, and adherents to the ideology of the mujahideen. In November 2001, as Operation Enduring Freedom had toppled the Taliban government, many Brigade 055 fighters were captured or killed, and those who survived were thought to have escaped into Pakistan along with bin Laden.[57]

By the end of 2008, some sources reported that the Taliban had severed any remaining ties with Al-Qaeda,[58] however, there is reason to doubt this.[59] According to senior US military intelligence officials, there were fewer than 100 members of Al-Qaeda remaining in Afghanistan in 2009.[60]

Al Qaeda chief, Asim Omar was killed in Afghanistan's Musa Qala district after a joint US–Afghanistan commando airstrike on September 23, Afghan's National Directorate of Security (NDS) confirmed in October 2019.[61]

In a report released May 27, 2020, the United Nations' Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team stated that the Taliban-Al Qaeda relations remain strong to this day and additionally, Al Qaeda itself has admitted that it operates inside Afghanistan.[62]

On July 26, 2020, a United Nations report stated that the Al Qaeda group is still active in twelve provinces in Afghanistan and its leader al-Zawahiri is still based in the country.[63] and that the UN Monitoring Team estimated that the total number of Al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan were "between 400 and 600".[63]

Call for global Salafi jihadism

In 1994, the Salafi groups waging Salafi jihadism in Bosnia entered into decline, and groups such as the Egyptian Islamic Jihad began to drift away from the Salafi cause in Europe. Al-Qaeda stepped in and assumed control of around 80% of non-state armed cells in Bosnia in late 1995. At the same time, Al-Qaeda ideologues instructed the network's recruiters to look for Jihadi international Muslims who believed that extremist-jihad must be fought on a global level. Al-Qaeda also sought to open the "offensive phase" of the global Salafi jihad.[64] Bosnian Islamists in 2006 called for "solidarity with Islamic causes around the world", supporting the insurgents in Kashmir and Iraq as well as the groups fighting for a Palestinian state.[65]

Fatwas

In 1996, Al-Qaeda announced its jihad to expel foreign troops and interests from what they considered Islamic lands. Bin Laden issued a fatwa,[66] which amounted to a public declaration of war against the US and its allies, and began to refocus Al-Qaeda's resources on large-scale, propagandist strikes.

On February 23, 1998, bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, a leader of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, along with three other Islamist leaders, co-signed and issued a fatwa calling on Muslims to kill Americans and their allies.[67] Under the banner of the World Islamic Front for Combat Against the Jews and Crusaders, they declared:

[T]he ruling to kill the Americans and their allies – civilians and military – is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it, to liberate the al-Aqsa Mosque [in Jerusalem] and the holy mosque [in Mecca] from their grip, and for their armies to move out of all the lands of Islam, defeated and unable to threaten any Muslim. This is in accordance with the words of Almighty Allah, 'and fight the pagans all together as they fight you all together [and] fight them until there is no more tumult or oppression, and there prevail justice and faith in Allah.'[68]

Neither bin Laden nor al-Zawahiri possessed the traditional Islamic scholarly qualifications to issue a fatwa. However, they rejected the authority of the contemporary ulema (which they saw as the paid servants of jahiliyya rulers), and took it upon themselves.[69][unreliable source?]

Philippines

Al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorist Ramzi Yousef operated in the Philippines in the mid-1990s and trained Abu Sayyaf soldiers.[70] The 2002 edition of the United States Department's Patterns of Global Terrorism mention links of Abu Sayyaf to Al-Qaeda.[71] Abu Sayyaf is known for a series of kidnappings from tourists in both the Philippines and Malaysia that netted them large sums of money through ransoms. The leader of Abu Sayyaf, Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani, was also a veteran fighting in the Soviet-Afghan War.[72] In 2014, Abu Sayyaf pledged allegiance to the Islamic State group.[73]

Iraq

Al-Qaeda has launched attacks against the Iraqi Shia majority in an attempt to incite sectarian violence.[74] Al-Zarqawi purportedly declared an all-out war on Shiites[75] while claiming responsibility for Shiite mosque bombings.[76] The same month, a statement claiming to be from Al-Qaeda in Iraq was rejected as a "fake".[77] In a December 2007 video, al-Zawahiri defended the Islamic State in Iraq, but distanced himself from the attacks against civilians, which he deemed to be perpetrated by "hypocrites and traitors existing among the ranks".[78]

US and Iraqi officials accused Al-Qaeda in Iraq of trying to slide Iraq into a full-scale civil war between Iraq's Shiite population and Sunni Arabs. This was done through an orchestrated campaign of civilian massacres and a number of provocative attacks against high-profile religious targets.[79] With attacks including the 2003 Imam Ali Mosque bombing, the 2004 Day of Ashura and Karbala and Najaf bombings, the 2006 first al-Askari Mosque bombing in Samarra, the deadly single-day series of bombings in which at least 215 people were killed in Baghdad's Shiite district of Sadr City, and the second al-Askari bombing in 2007, Al-Qaeda in Iraq provoked Shiite militias to unleash a wave of retaliatory attacks, resulting in death squad-style killings and further sectarian violence which escalated in 2006.[80] In 2008, sectarian bombings blamed on Al-Qaeda in Iraq killed at least 42 people at the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala in March, and at least 51 people at a bus stop in Baghdad in June.

In February 2014, after a prolonged dispute with Al-Qaeda in Iraq's successor organisation, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), Al-Qaeda publicly announced it was cutting all ties with the group, reportedly for its brutality and "notorious intractability".[81]

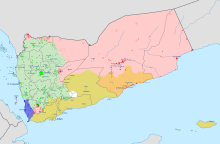

Somalia and Yemen

In Somalia, Al-Qaeda agents had been collaborating closely with its Somali wing, which was created from the al-Shabaab group. In February 2012, al-Shabaab officially joined Al-Qaeda, declaring loyalty in a video.[82] Somali Al-Qaeda recruited children for suicide-bomber training and recruited young people to participate in militant actions against Americans.[83]

The percentage of attacks in the First World originating from the Afghanistan–Pakistan (AfPak) border declined starting in 2007, as Al-Qaeda shifted to Somalia and Yemen.[84] While Al-Qaeda leaders were hiding in the tribal areas along the AfPak border, middle-tier leaders heightened activity in Somalia and Yemen.

In January 2009, Al-Qaeda's division in Saudi Arabia merged with its Yemeni wing to form Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).[85] Centered in Yemen, the group takes advantage of the country's poor economy, demography and domestic security. In August 2009, the group made an assassination attempt against a member of the Saudi royal family. President Obama asked Ali Abdullah Saleh to ensure closer cooperation with the US in the struggle against the growing activity of Al-Qaeda in Yemen, and promised to send additional aid. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan drew US attention from Somalia and Yemen.[86] In December 2011, US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta said the US operations against Al-Qaeda "are now concentrating on key groups in Yemen, Somalia and North Africa."[87] Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula claimed responsibility for the 2009 bombing attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253 by Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab.[88] The AQAP declared the Al-Qaeda Emirate in Yemen on March 31, 2011, after capturing most of the Abyan Governorate.[89]

As the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen escalated in July 2015, fifty civilians had been killed and twenty million needed aid.[90] In February 2016, Al-Qaeda forces and Saudi Arabian-led coalition forces were both seen fighting Houthi rebels in the same battle.[91] In August 2018, Al Jazeera reported that "A military coalition battling Houthi rebels secured secret deals with Al-Qaeda in Yemen and recruited hundreds of the group's fighters. ... Key figures in the deal-making said the United States was aware of the arrangements and held off on drone attacks against the armed group, which was created by Osama bin Laden in 1988."[92]

United States operations

In December 1998, the Director of the CIA Counterterrorism Center reported to President Bill Clinton that Al-Qaeda was preparing to launch attacks in the United States, and the group was training personnel to hijack aircraft.[93] On September 11, 2001, Al-Qaeda attacked the United States, hijacking four airliners within the country and deliberately crashing two into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. The third plane crashed into the western side of the Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia. The fourth plane was crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania.[94] In total, the attackers killed 2,977 victims and injured more than 6,000 others.[95]

US officials noted that Anwar al-Awlaki had considerable reach within the US. A former FBI agent identified Awlaki as a known "senior recruiter for Al-Qaeda", and a spiritual motivator.[96] Awlaki's sermons in the US were attended by three of the 9/11 hijackers, and accused Fort Hood shooter Nidal Hasan. US intelligence intercepted emails from Hasan to Awlaki between December 2008 and early 2009. On his website, Awlaki has praised Hasan's actions in the Fort Hood shooting.[97]

An unnamed official claimed there was good reason to believe Awlaki "has been involved in very serious terrorist activities since leaving the US [in 2002], including plotting attacks against America and our allies."[98] US President Barack Obama approved the targeted killing of al-Awlaki by April 2010, making al-Awlaki the first US citizen ever placed on the CIA target list. That required the consent of the US National Security Council, and officials argued that the attack was appropriate because the individual posed an imminent danger to national security.[99][100][101] In May 2010, Faisal Shahzad, who pleaded guilty to the 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt, told interrogators he was "inspired by" al-Awlaki, and sources said Shahzad had made contact with al-Awlaki over the Internet.[102][103][104] Representative Jane Harman called him "terrorist number one", and Investor's Business Daily called him "the world's most dangerous man".[105][106] In July 2010, the US Treasury Department added him to its list of Specially Designated Global Terrorists, and the UN added him to its list of individuals associated with Al-Qaeda.[107] In August 2010, al-Awlaki's father initiated a lawsuit against the US government with the American Civil Liberties Union, challenging its order to kill al-Awlaki.[108] In October 2010, US and UK officials linked al-Awlaki to the 2010 cargo plane bomb plot.[109] In September 2011, al-Awlaki was killed in a targeted killing drone attack in Yemen.[110] On March 16, 2012, it was reported that Osama bin Laden plotted to kill US President Barack Obama.[111]

Killing of Osama bin Laden

On May 1, 2011, US President Barack Obama announced that Osama bin Laden had been killed by "a small team of Americans" acting under direct orders, in a covert operation in Abbottabad, Pakistan.[112][113] The action took place 50 km (31 mi) north of Islamabad.[114] According to US officials, a team of 20–25 US Navy SEALs under the command of the Joint Special Operations Command stormed bin Laden's compound with two helicopters. Bin Laden and those with him were killed during a firefight in which US forces experienced no casualties.[115] According to one US official the attack was carried out without the knowledge or consent of the Pakistani authorities.[116] In Pakistan some people were reported to be shocked at the unauthorized incursion by US armed forces.[117] The site is a few miles from the Pakistan Military Academy in Kakul.[118] In his broadcast announcement President Obama said that US forces "took care to avoid civilian casualties".[119]

Details soon emerged that three men and a woman were killed along with bin Laden, the woman being killed when she was "used as a shield by a male combatant".[116] DNA from bin Laden's body, compared with DNA samples on record from his dead sister,[120] confirmed bin Laden's identity.[121] The body was recovered by the US military and was in its custody[113] until, according to one US official, his body was buried at sea according to Islamic traditions.[114][122] One US official said that "finding a country willing to accept the remains of the world's most wanted terrorist would have been difficult."[123] US State Department issued a "Worldwide caution" for Americans following bin Laden's death and US diplomatic facilities everywhere were placed on high alert, a senior US official said.[124] Crowds gathered outside the White House and in New York City's Times Square to celebrate bin Laden's death.[125]

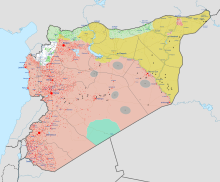

Syria

In 2003, President Bashar al-Assad revealed in an interview with a Kuwaiti newspaper that he doubted Al-Qaeda even existed. He was quoted as saying, "Is there really an entity called Al-Qaeda? Was it in Afghanistan? Does it exist now?" He went on further to remark about bin Laden, commenting "[he] cannot talk on the phone or use the Internet, but he can direct communications to the four corners of the world? This is illogical."[127]

Following the mass protests that took place in 2011, which demanded the resignation of al-Assad, Al-Qaeda-affiliated groups and Sunni sympathizers soon began to constitute an effective fighting force against al-Assad.[128] Before the Syrian Civil War, Al-Qaeda's presence in Syria was negligible, but its growth thereafter was rapid.[129] Groups such as the al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant have recruited many foreign Mujahideen to train and fight in what has gradually become a highly sectarian war.[130][131] Ideologically, the Syrian Civil War has served the interests of Al-Qaeda as it pits a mainly Sunni opposition against a secular government. Al-Qaeda and other fundamentalist Sunni militant groups have invested heavily in the civil conflict, at times actively backing and supporting the mainstream Syrian Opposition.[132][133]

On February 2, 2014, Al-Qaeda distanced itself from ISIS and its actions in Syria;[134] however, during 2014–15, ISIS and the Al-Qaeda-linked al-Nusra Front[135] were still able to occasionally cooperate in their fight against the Syrian government.[136][137][138] Al-Nusra (backed by Saudi Arabia and Turkey as part of the Army of Conquest during 2015–2017[139]) launched many attacks and bombings, mostly against targets affiliated with or supportive of the Syrian government.[140] From October 2015, Russian air strikes targeted positions held by al-Nusra Front, as well as other Islamist and non-Islamist rebels,[141][142][143] while the US also targeted al-Nusra with airstrikes.[143][144][145] In early 2016, a leading ISIL ideologue described Al-Qaeda as the "Jews of jihad".[146]

India

In September 2014, al-Zawahiri announced Al-Qaeda was establishing a front in India to "wage jihad against its enemies, to liberate its land, to restore its sovereignty, and to revive its Caliphate." Al-Zawahiri nominated India as a beachhead for regional jihad taking in neighboring countries such as Myanmar and Bangladesh. The motivation for the video was questioned, as it appeared the militant group was struggling to remain relevant in light of the emerging prominence of ISIS.[147] The new wing was to be known as "Qaedat al-Jihad fi'shibhi al-qarrat al-Hindiya" or al-Qaida in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS). Leaders of several Indian Muslim organizations rejected al-Zawahiri's pronouncement, saying they could see no good coming from it, and viewed it as a threat to Muslim youth in the country.[148]

In 2014, Zee News reported that Bruce Riedel, a former CIA analyst and National Security Council official for South Asia, had accused the Pakistani military intelligence and Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) of organising and assisting Al-Qaeda to organise in India, that Pakistan ought to be warned that it will be placed on the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism, and that "Zawahiri made the tape in his hideout in Pakistan, no doubt, and many Indians suspect the ISI is helping to protect him."[149][150][151]

In September 2021, after the success of 2021 Taliban offensive, Al-Qaeda congratulated Taliban and called for liberation of Kashmir from the "clutches of the enemies of Islam".[152]

References

- ^ Burke, Jason & Allen, Paddy (September 10, 2009). "The five ages of al-Qaida". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ a b United States v. Usama bin Laden et al., S (7) 98 Cr. 1023, Testimony of Jamal Ahmed Mohamed al-Fadl (SDNY February 6, 2001).

"Al-Qaeda's origins and links". BBC News. July 20, 2004. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

Cooley, John K. (Spring 2003). Unholy Wars: Afghanistan, America and International Terrorism. - ^ "1986–1992: CIA and British Recruit and Train Militants Worldwide to Help Fight Afghan War". Cooperative Research History Commons. Archived from the original on August 18, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Bergen, Peter L., Holy war, Inc.: inside the secret world of Osama bin Laden, New York: Free Press, 2001. pp. 68–x69

- ^ Bergen, Peter L., Holy war, Inc.: Inside the Secret World of Osama bin Laden, New York: Free Press, 2001., pp. 70–71

- ^ Filiu, Jean-Pierre (12 November 2009). "The Brotherhood vs. Al-Qaeda: A Moment of Truth?". Current Trends in Islamist Ideology. 9: 19. ProQuest 1438649412 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Filiu, Jean-Pierre (12 November 2009). "The Brotherhood vs. Al-Qaeda: A Moment of Truth?". Current Trends in Islamist Ideology. 9: 19–20. ProQuest 1438649412 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Wright 2006.

- ^ Gunaratna 2002, p. 19. Quotes taken from Riedel 2008, p. 42 and Wright 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Filiu, Jean-Pierre (12 November 2009). "The Brotherhood vs. Al-Qaeda: A Moment of Truth?". Current Trends in Islamist Ideology. 9: 20. ProQuest 1438649412 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Cloonan Frontline interview, PBS, July 13, 2005.

- ^ Sageman 2004, p. 35.

- ^ Wright 2006, p. 137.

- ^ "The War on Terror and the Politics of Violence in Pakistan". The Jamestown Foundation. July 2, 2004. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ "Who Is Osama Bin Laden?". Forbes. September 14, 2001.

- ^ "Frankenstein the CIA created". January 17, 1999. The Guardian.

- ^ Cook, Robin (July 8, 2005). "The struggle against terrorism cannot be won by military means". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on July 10, 2005. Retrieved July 8, 2005.

- ^ Akram, Munir (January 19, 2008). "Pakistan, Terrorism and Drugs". Opinion. The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ Bergen, Peter L. (August 2, 2022). The Rise and Fall of Osama Bin Laden. Simon and Schuster. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-9821-7053-0.

- ^ a b Coll 2005, pp. 145–46, 155–56

- ^ Bergen, Peter. "Bergen: Bin Laden, CIA links hogwash". CNN. Archived from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2006.

- ^ "Frankenstein the CIA created". The Guardian. January 17, 1999.

- ^ Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, Chapter on Terrorist Financing, 9/11 Commission Report Archived January 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine p. 104

- ^ Bergen 2006, p. 75.

- ^ "Bill Moyers Journal. A Brief History of Al Qaeda". PBS.com. July 27, 2007. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ Wright 2008.

- ^ a b "Osama bin Laden: The Past". Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- ^ Jihadi Terrorism and the Radicalisation Challenge: p.219, Rik Coolsaet – 2011

- ^ Wright 2006, pp. 133–34.

- ^ Al-Bahri, Nasser, Guarding bin Laden: My Life in al-Qaeda. p. 123. Thin Man Press. London. ISBN 9780956247360

- ^ Wright 2006, p. 260.

- ^ Gunaratna, Rohan (2007). "The evolution of al Qaeda". In Biersteker, Thomas J.; Eckert, Sue E. (eds.). Countering the Financing of Terrorism. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-134-15537-8.

- ^ Wright 2006, p. 181.

- ^ a b Fisk, Robert (21 September 1998). "Talks With Osama bin Laden". The Nation. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Bin Laden 'deliberately' wanted to tarnish Saudi-US relations: Western intelligence". Arab News. 3 August 2018. Archived from the original on 19 June 2023.

- ^ Riedel, Bruce (15 August 2019). "Saudi Arabia and the civil war within Yemen's civil war". Brookings. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023.

- ^ Jehl, Douglas (December 27, 2001). "A Nation Challenged: Holy war lured Saudis as rulers looked away". The New York Times. pp. A1, B4. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "The spider in the web". The Economist. 20 September 2001. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023.

- ^ Scheuer, Michael (2006). "8: Bin Laden and the Saudis, 1989-1991: From Favourite Son to Black Sheep". Through Our Enemys' Eyes (2nd ed.). Dulles, Virginia 20166, USA: Potomac Books Inc. pp. 119–128. ISBN 1-57488-967-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Riedel 2008, p. 52.

- ^ Wright 2006, p. 195.

- ^ "Osama bin Laden: A Chronology of His Political Life". PBS. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- ^ "Context of 'Shortly After April 1994'". Cooperative Research History Commons. Archived from the original on August 19, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- ^ Wright 2006, p. 186.

- ^ bin Laden, Osama (7 June 1994). "Saudi Arabia supports the Communists in Yemen" (PDF). Institutional Scholarship. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2023.

- ^ Ijaz, Mansoor (December 5, 2001). "Clinton Let Bin Laden Slip Away and Metastasize". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Carney, Timothy; Ijaz, Mansoor (June 30, 2002). "Intelligence Failure? Let's Go Back to Sudan". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ Rose, David (January 2002). "The Osama Files". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ Belz, Mindy (November 1, 2003). "Clinton did not have the will to respond". World. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ "National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States". Govinfo.library.unt.edu. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Rashid 2002.

- ^ Napoleoni 2003, pp. 121–23; Akacem 2005 "Napoleoni does a decent job of covering al-Qaida and presents some numbers and estimates that are of value to terrorism scholars."

- ^ Kronstadt & Katzman 2008.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda Core: A Case Study, p. 11" (PDF). cna.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Miller, Flagg (2015). The Audacious Ascetic: What the Bin Laden Tapes Reveal about al-Qaʿida. Madison Avenue, New York, USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 249–251. ISBN 978-0-19-026436-9.

- ^ a b Fisk, Robert (10 July 1996). "Arab rebel leader warns the British: 'Get out of the Gulf'". Independent. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel (October 28, 2001). "Secrets of Brigade 055". Time. Archived from the original on November 3, 2001.

- ^ Robertson, Nic. "Sources: Taliban split with al Qaeda, seek peace". CNN. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Roggio, Bill Taliban have not split from al Qaeda: sources October 7, 2008 The Long War Journal

- ^ Partlow, Joshua. In Afghanistan, Taliban surpasses al-Qaeda" November 11, 2009

- ^ Snow, Shawn (October 8, 2019). "Major al-Qaida leader killed in joint US-Afghan raid". Military Times. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ "Eleventh report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2501 (2019) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace, stability and security of Afghanistan". United Nations Security Council. May 27, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ a b "Al Qaeda active in 12 Afghan provinces: UN". daijiworld.com. July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Sageman 2004, pp. 48, 51.

- ^ Trofimov 2006, p. 282.

- ^ "Bin Laden's Fatwa". Al Quds Al Arabi. August 1996. Archived from the original on January 8, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Summary taken from bin Laden's May 26, 1998, interview with American journalist John Miller. Most recently broadcast in the documentary Age of Terror, part 4, with translations checked by Barry Purkis (archive researcher).

- ^ "Text of Fatwah Urging Jihad Against Americans". Archived from the original on April 22, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2006.

- ^ Benjamin & Simon 2002, p. 117. "By issuing fatwas, bin Laden and his followers are acting out a kind of self-appointment as alim: they are asserting their rights as interpreters of Islamic law."

- ^ Banlaoi, Rommel (2004). War on Terrorism in Southeast Asia. Quezon City: Rex Book Store. pp. 1–235. ISBN 978-971-23-4031-4.

- ^ "Gunfight in philippine bomber hunt". CNN. August 10, 2003.

- ^ "The Abu Sayyaf-Al Qaeda Connection". ABC News.

- ^ "The Philippines: Extremism and Terrorism".

- ^ Al Qaeda's hand in tipping Iraq toward civil war, The Christian Science Monitor/Al-Quds Al-Arabi, March 20, 2006

- ^ "Another wave of bombings hit Iraq". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. September 15, 2005. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009.

- ^ "20 die as insurgents in Iraq target Shiites". International Herald Tribune. September 17, 2005. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda disowns 'fake letter'", CNN, October 13, 2005

- ^ "British 'fleeing' claims al-Qaeda". Adnkronos.com. April 7, 2003. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ "Al Qaeda leader in Iraq 'killed by insurgents'". ABC News. May 1, 2007. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen/Pincus, Walter. "Al-Qaeda in Iraq May Not Be Threat Here", The Washington Post, March 18, 2007

- ^ Sly, Liz (February 3, 2014). "Al-Qaeda disavows any ties with radical Islamist ISIS group in Syria, Iraq". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ "Somalia's al-Shabab join al-Qaeda". BBC. February 10, 2012.

- ^ "Al-Shabaab joining al Qaeda, monitor group says". CNN. February 9, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ Johnston, Philip (September 17, 2010). "Anwar al Awlaki: the new Osama bin Laden?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- ^ "NEWS.BBC.co.uk". BBC. January 3, 2010. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda Slowly Makes Its Way to Somalia and Yemen". Pravda.ru. September 15, 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ "Hunt for terrorists shifts to 'dangerous' North Africa, Panetta says". NBC News. Archived from the original on May 8, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ^ "Al Qaeda: We Planned Flight 253 Bombing Terrorist Group Says It Was In Retaliation for U.S. Operation in Yemen; Obama Orders Reviews of Watchlist and Air Safety". CBS News. December 28, 2009. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Wyler, Grace (March 31, 2011). "AQAP: Abyan province an "Islamic Emirate."". Business Insider. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Jihadis likely winners of Saudi Arabia's futile war on Yemen's Houthi rebels". The Guardian. July 7, 2015.

- ^ "Yemen conflict: Al-Qaeda joins coalition battle for Taiz". BBC. February 22, 2016.

- ^ "Report: Saudi-UAE coalition 'cut deals' with al-Qaeda in Yemen". Al-Jazeera. August 6, 2018.

- ^ "Bin Laden Preparing to Hijack US Aircraft and Other Attacks". Director of Central Intelligence. December 4, 1998. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2010.

- ^ National Commission on Terrorist Attacks (July 22, 2004). The 9/11 Commission Report (first ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32671-3.

- ^ "Lost lives remembered during 9/11 ceremony". The Online Rocket. September 12, 2008. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Chucmach, Megan, and Ross, Brian, "Al Qaeda Recruiter New Focus in Fort Hood Killings Investigation Army Major Nidal Hasan Was In Contact With Imam Anwar Awlaki, Officials Say," ABC News, November 10, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009

- ^ Esposito, Richard, Cole, Matthew, and Ross, Brian, "Officials: US Army Told of Hasan's Contacts with al Qaeda; Army Major in Fort Hood Massacre Used 'Electronic Means' to Connect with Terrorists," ABC News, November 9, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009

- ^ "Imam From Va. Mosque Now Thought to Have Aided Al-Qaeda" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Miller, Greg (April 6, 2010). "Muslim cleric Aulaqi is 1st U.S. citizen on list of those CIA is allowed to kill". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Shane, Scott (April 6, 2010). "U.S. Approves Targeted Killing of American Cleric". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ Leonard, Tom (April 7, 2010). "Barack Obama orders killing of US cleric Anwar al-Awlaki". Telegraph (UK). London. Archived from the original on April 11, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ Dreazen, Yochi J.; Perez, Evan (May 6, 2010). "Suspect Cites Radical Imam's Writings". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Herridge, Catherine (May 6, 2010). "Times Square Bomb Suspect a 'Fan' of Prominent Radical Cleric, Sources Say". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on May 7, 2010. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Esposito, Richard; Vlasto, Chris; Cuomo, Chris (May 6, 2010). "Faisal Shahzad Had Contact With Anwar Awlaki, Taliban, and Mumbai Massacre Mastermind, Officials Say". The Blotter from Brian Ross. ABC News. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Fisher, Max (September 30, 2011). "Anwar Who?". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ May 10, 2010, editorial in the Investor's Business Daily

- ^ "Awlaki lands on al-Qaida suspect list". United Press International. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Mark (August 5, 2010). "CIA on the verge of lawsuit" (PDF). Seer Press News. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Rayment, Sean; Hennessy, Patrick; Barrett, David (October 30, 2010). "Yemen cargo bomb plot may have been targeted at Britain". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ Zenko, Micah. (September 30, 2011) Targeted Killings: The Death of Anwar al-Awlaki Archived April 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ^ "Osama Bin Laden 'plotted to kill Obama' before death". BBC News. March 17, 2012.

- ^ Adams, Richard; Walsh, Declan; MacAskill, Ewen (May 1, 2011). "Osama bin Laden is dead, Obama announces". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b "Osama Bin Laden Killed by US Strike". ABC News. May 1, 2011.

- ^ a b the CNN Wire (May 2, 2011). "How U.S. forces killed Osama bin Laden". Cable News Network. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Osama Bin Laden Killed By Navy Seals in Firefight". ABC News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Balz, Dan (May 2, 2011). "Osama bin Laden is killed by U.S. forces in Pakistan". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Chitralis bewildered at OBL episode". Chitralnews.com. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ "Osama bin Laden, the face of terror, killed in Pakistan". CNN. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on May 6, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ "Osama Bin Laden Dead: Obama Speech Video And Transcript" The Huffington Post, May 2, 2011

- ^ "Report: DNA At Mass. General Confirms bin Laden's Death". Thebostonchannel.com. February 5, 2011. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ "Osama bin Laden Killed; ID Confirmed by DNA Testing". ABC News. May 1, 2011.

- ^ "US forces kill Osama bin Laden in Pakistan". MSN. May 2, 2011.

- ^ "Official: Bin Laden buried at sea". Yahoo! News. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. forces kill elusive terror figure Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan". CNN. May 2, 2011.

- ^ "Crowds celebrate Bin Laden's death". Euronews. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ "With wary eye, Syrian rebels welcome Islamists into their ranks". The Times of Israel. October 25, 2012.

- ^ "Assad doubts existence of al-Qaeda". USA Today. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Berezow, Alex (September 30, 2013). "Al-Qaeda Goes Global". RealClearWorld. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Neumann, Peter (2014). "Suspects into Collaborators". London Review of Books. 36 (7): 19–21. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ "Opinion: Syria plunging Mideast into sectarian war?". CNN. September 4, 2013.

- ^ Cowell, Alan. "Syria – Uprising and Civil War". The New York Times. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Syria: On the frontline with the Free Syrian Army in Aleppo". FRANCE 24. October 4, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Al Nusra Front, an al Qaeda branch, and the Free Syrian Army jointly seize border crossing". The Washington Times. September 30, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda disavows ISIS militants in Syria". BBC News. February 3, 2014.

- ^ "Gulf allies and 'Army of Conquest' Archived September 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine". Al-Ahram Weekly. May 28, 2015.

- ^ Banco, Erin (April 11, 2015). "Jabhat Al-Nusra And ISIS Alliance Could Spread Beyond Damascus". International Business Times.

- ^ "How would a deal between al-Qaeda and Isil change Syria's civil war?". The Daily Telegraph. November 14, 2014

- ^ "ISIS joins other rebels to thwart Syria regime push near Lebanon". The Sacramento Bee. McClatchy DC. March 4, 2014. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- ^ Sengupta, Kim (May 12, 2015). "Turkey and Saudi Arabia alarm the West by backing Islamist extremists the Americans had bombed in Syria". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 13, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "Syria's al-Qaeda offshoot Nusra stages suicide bombing in Aleppo: monitor Archived October 31, 2015, at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. July 6, 2015.

- ^ "Russia launches media offensive on Syria bombing". BBC News. October 1, 2015.

- ^ Pantucci, Raf (November 15, 2016). "Russia launches major offensive in Syria with airstrikes on Idlib and Homs, as rebel-held east Aleppo bombarded for first time in weeks". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Syria at War: As U.S. Bombs Rebels, Russia Strikes ISIS and Israel Targets Assad Newsweek March 17, 2017

- ^ The United States Is Bombing First, Asking Questions Later, Foreign Policy 3 April 2017

- ^ U.S. Airstrike Kills More Than 100 Qaeda Fighters in Syria New York Times January 20, 2017

- ^ Moore, Jack (January 25, 2016). "ISIS ideologue calls al-Qaeda the 'Jews of jihad' as rivalry continues". Newsweek. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ "India security alert after Al Qaeda calls for jihad in subcontinent". India Gazette. September 4, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ^ "Indian Muslims Reject al-Qaida call for Jihad". India Gazette. September 6, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ^ "Al Qaeda launches India wing: 'Pakistan Army, ISI targeting India to hit Nawaz Sharif'". Zee News. September 6, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "al-Qaeda's wing in India: Pakistan's ISI exposed over threatening video". news.oneindia.in. September 4, 2014. Archived from the original on September 27, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "Danger from ISIS and Al Qaeda: What India should do". news.oneindia.in. September 5, 2014. Archived from the original on September 28, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda congratulates Taliban, calls for Kashmir 'liberation'". Hindustan Times. September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

Bibliography

- Coll, Steve (2005-03-03). Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-193579-9.

- Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-41486-X.

- Gunaratna, Rohan (2002). Inside Al Qaeda (1st ed.). London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 1-85065-671-1.

- Riedel, Bruce (2008). The Search for al Qaeda: Its Leadership, Ideology, and Future. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-7414-3.

- Sageman, Marc (2004). Understanding Terror Networks. Vol. 7. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 5–8. ISBN 0-8122-3808-7. PMID 15869076.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Bergen, Peter (2006). The Osama bin Laden I Know: An Oral History of al Qaeda's Leader (2nd ed.). New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-7892-5.

- Wright, Lawrence (June 2, 2008). "The Rebellion Within". The New Yorker. Vol. 84, no. 16. pp. 36–53. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- Trofimov, Yaroslav (2006). Faith at War: A Journey On the Frontlines of Islam, From Baghdad to Timbuktu. New York: Picador. ISBN 978-0-8050-7754-4.

- Rashid, Ahmed (2002) [2000]. Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 1-86064-830-4.

- Napoleoni, Loretta (2003). Modern Jihad: Tracing the Dollars Behind the Terror Networks. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-2117-8.

- Kronstadt, K. Allen; Katzman, Kenneth (November 2008). "Islamist Militancy in the Pakistan-Afghanistan Border Region and U.S. Policy" (PDF). US Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Akacem, Mohammed (August 2005). "Review: Modern Jihad: Tracing the Dollars behind the Terror Networks". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 37 (3): 444–445. doi:10.1017/S0020743805362143. S2CID 162390565.

- Benjamin, Daniel; Simon, Steven (2002). The Age of Sacred Terror (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50859-7.