Abortion in Romania

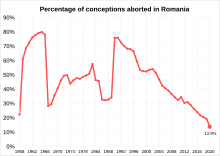

Abortion in Romania is currently legal as an elective procedure during the first 14 weeks of pregnancy, and for medical reasons at later stages of pregnancy.[1] In the year 2004, there were 216,261 live births and 191,000 reported abortions,[2] meaning that 46% of the 407,261 reported pregnancies that year ended in abortion.

In 2021 an article was published by NPR raising concerns that abortion access is becoming restricted in Romania. During the Coronavirus Pandemic in 2020, the government's published list of services public hospitals were required to perform did not include abortions. This policy pushed women to seek abortion care at private hospitals, where costs were much higher. In April of 2020, the government told public hospitals to resume abortion services, but according to abortion activist Andrada Cilibiu when speaking with NPR, many public hospitals continued to turn patients away. In June 2020 only 55 out of the 134 public hospitals in Romania were providing abortions, and in June 2021, that number dropped all the way down to 28.[3]

Abortion was also legal on-demand in Romania from 1957 to 1966.[4] From 1967 to 1990 abortion was severely restricted, in an effort of the Communist leadership to increase the fertility rate of the country; however this resulted in rising mortality rates and a surge in Orphans. After the Romanian Revolution abortion laws were loosened.

History

Before communism

Abortion was illegal in Romania as in other European countries, but Romania's punishment for abortion was less severe compared to many other European countries during that historical period. The Penal Code of 1865, which followed shortly after the union of the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, and was in force between 1865 and 1936, banned abortion. Article 246 punished the person who performed the abortion with "minimul recluziunei" (a shorter form of imprisonment), while the pregnant woman who procured her own abortion could be punished with 6 months' to 2 years' imprisonment. The punishment increased for the persons who performed abortion if they were medical workers, or if the pregnant woman died.[5]

Abortion remained illegal under Romania's 1936 Criminal Code, except if needed to save the pregnant woman's life or if the child risked inheriting a severe genetic disorder. Articles 482–485 of that code dealt with abortion.[6] The punishment for both the person performing an abortion and the pregnant woman who procured the abortion were 3–6 months if she was unmarried; and 6 months–1 year if she was married. The punishments increased if the woman didn't consent to the abortion, if she was severely injured, or if she died. Medical personnel or pharmacists involved in performing abortions were barred for practicing the profession for 1–3 years. The significance of such legal provisions must be understood in an international context: for instance as late as 1943, in France, abortionist Marie-Louise Giraud was executed for performing abortions.

Abortion on demand was first legalized in Romanian in 1957 and stayed legal until 1966, when it was again outlawed by Nicolae Ceaușescu. It was legalized again after the Romanian Revolution.

During the communist regime

While Romania became a communist state at the end of 1947, this section focuses on the time period from 1966 to 1989 during Nicolae Ceaușescu's rule.

Decree 770

In 1957 the procedure was officially legalized in Romania, following which 80% of pregnancies ended in abortion, mainly due to the lack of effective contraception. By 1966, the national birthrate had fallen from 19.1 per 1,000 in 1960 to 14.3 per 1,000, a decline that was attributed to the legalization of abortion nine years previously.[7] In an effort to ensure "normal demographic growth", Decree 770 was authorized by Nicolae Ceaușescu's government. The decree criminalized abortion except in the following cases:

- women over 45 (lowered to 40 in 1974, raised back to 45 in 1985)[7][8]

- women who had already delivered and reared four children (raised to five in 1985)[7][8]

- women whose life would be threatened by carrying to term due to medical complications[7][8]

- women whose fetuses were malformed[9]

- women who were pregnant through rape or incest[7][8]

The effect of this policy was a sudden transition from a birth rate of 14.3 per 1,000 in 1966 to 27.4 per 1,000 in 1967, though it fell back to 14.3 in 1983.[7]

Initially, this natalist policy was completed with mandatory gynecological revisions and penalties for single women over 25 and married couples without children,[8] but starting in 1977, all "childless persons", regardless of sex or marital status, were fined monthly "contributions" from their wages, whose size depended on the sector in which the person worked.[7] The state glorified child-rearing, and in 1977 assigned official decorations and titles to women who went above and beyond the call of duty and had more than the required number of children.[7]

Upon the death of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej in 1965, Ceaușescu succeeded to the leadership of Romanian Workers' Party as First Secretary. Like the previous leader, Ceaușescu officially promoted gender equality, but also desired to increase the nation's population.[7][10] In his rhetoric, he stressed the "distinguished role and noble mission" found in child-rearing, and promised state-sponsored assistance in the form of childcare centers, accessible medical care, maternity leave, and work protection so that women could combine large families with work outside the home.[7] Ceaușescu's ideas of mandating large families were inspired by the Stalinist USSR (abortion was illegal in USSR between 1936 and 1955), as well as by his own conservative upbringing in rural Olt county.[11] Ceaușescu promoted an ideal of the superwoman, active in the workforce, politically involved, raising many children, taking care of the household chores, and succeeding in doing all these at the same time. There were no attempts to provide for equitable sharing of chores within the family (between the husband and wife) – like most communist regimes, Romanian politics too considered it sufficient to promote gender equality in the public sphere, not the private one; the personal relations and gender roles within the family were ignored.[12] Ceaușescu's government was unable to provide much of its promised assistance to families, leaving many families in difficult situations and unable to cope,[7] with the natalist policy being a contributor to the severe problem of child abandonment, where large numbers of children ended living in Romanian orphanages, infamous for institutionalised neglect and abuse.[11] During the 1990s, the street children seen in Romanian cities were a reminder of this policy.[13] A relatively similar policy of restricted reproductive rights during that period also existed in Communist Albania, under Enver Hoxha.

The 1980s austerity policy in Romania, imposed by Ceaușescu in order to pay out the external debt incurred by the state in the 1970s, aggravated poverty in the country making it even more difficult to raise children. The vast majority of children who lived in the communist orphanages were not actually orphans, but were simply children whose parents could not afford to raise them.[14] There were also other social problems, in particular the overcrowding of both homes and school classrooms; as Ceaușescu's natalist policy also coincided with mass population migration from rural areas to cities.[15] Most of these families were housed in standardized apartment blocks that were built in large numbers across Romanian cities during systematization.

Ceaușescu's desire for large families proved unrealistic within Romanian society, which at the time was plagued by poverty, and where the state, despite its rhetoric, provided only nominal social benefits and programmes. As a result, rates of illegal abortions were very high, especially in big cities. Realizing that the demographic policies had not worked as planned, the government's campaigns became very aggressive after 1984: women of reproductive age were closely monitored, were required to undergo regular gynaecological examinations at their place of employment, and investigations were carried out to determine the cause of all miscarriages. Increased taxes on childlessness and on unmarried persons were enforced.[16] In 1985, a woman who worked at the APACA textile factory died after an illegal abortion, and her case was used by the authorities as an example on the necessity to avoid abortion and obey the law.[17][18] The maternal mortality rate in 1989 was the highest ever recorded in Europe.[19]

In addition to outlawing abortion, Ceaușescu also promoted early marriage (immediately after finishing school), made divorce very difficult to obtain, and criminalized homosexuality in the 1969 Criminal Code even if done in private and without "public scandal" (a difference from the previous 1936 code). The policies towards unmarried people were harsh: they received poor housing (named cămine de nefamiliști[20]) and were considered unfit citizens.

Enforcement of the decree and social control

To enforce the decree, society was strictly controlled. Motherhood was described as "the meaning of women's lives" and praised in sex education courses and women's magazines, and various written materials were distributed detailing information on prenatal and child care, the benefits of children, ways to ensure marital harmony, and the consequences of abortion.[7] Contraceptives disappeared from the shelves and were soon only available to educated urban women with access to the black market, many of them with Hungarian roots.[7] In 1986, any woman working for or attending a state institution was forced to undergo at least annual gynecological exams to ensure a satisfying level of reproductive health as well as detect pregnancies, which were followed until birth.[7] Women with histories of abortion were watched particularly carefully.[7]

Medical practitioners were also expected to follow stringent policies and were held partially responsible for the national birthrate. If they were caught breaking any aspect of the abortion law, they were to be incarcerated, though some prosecutors were paid off in exchange for a lesser sentence.[7] Each administrative region had a Disciplinary Board for Health Personnel, which disciplined all law-breaking health practitioners and on occasion had show trials to make examples of people. Sometimes, however, punishments were lessened for cooperation.[7] The Ob-Gyn chief of individual hospitals were appointment 'watchmen', responsible for meeting reproductive goals.[21] Despite the professional risks involved, many doctors helped women determined to have abortions, recognizing that if they did not, the women would turn to a more dangerous, life-threatening route. This was done by falsely diagnosing them with an illness that qualified them for an abortion, such as diabetes or hepatitis, or prescribing them drugs that were known to counter-induce pregnancy, such as chemotherapy or antimalarial drugs.[7] When a physician did not want to help or could not be bribed to perform an abortion, however, women went to less experienced abortionists or used old remedies.[7]

From 1979 to 1988, the number of abortions increased, save for a decline in 1984–1985.[7] Despite this, many unplanned children were born; as their parents could scarcely afford to care for the children they already had, they were subsequently abandoned in hospitals or orphanages. Some of these children were purposely given AIDS-infected transfusions in orphanages; others were trafficked internationally through adoption.[7] Those born in this period, especially between 1966 and 1972, are nicknamed the decreței (singular decrețel), a word with a negative nuance due to the perceived mental and physical damage due to the risky pregnancies and failed illegal abortions.[22] Over 9,000 women died between 1965 and 1989 due to complications arising from illegal abortions.[7]

After 1989

This policy was reversed in 1990, after the Romanian Revolution, and, since that time, abortion has been legal on request in Romania. By 1990, abortions outnumbered live births 3:1.[23]

There have been attempts to restrict the practice of abortion, such as in 2012, when Sulfina Barbu, an MP of the Democratic Liberal Party, proposed a legislative initiative requiring women wanting to undergo an abortion to attend psychological counseling sessions, and to "reflect" for five days. Such attempts have been criticized as being motivated by the demographic downfall of Romania.[24]

Mifepristone (medical abortion) was registered in 2008.[25][26]

Legal framework under the 2014 Penal Code

The new Penal Code, which came into force in 2014, regulates the procedure of abortion. Article 201 (1) punishes the performing of an abortion when done under any of these following circumstances: (a) outside medical institutions or medical offices authorized for this purpose; (b) by a person who is not a certified physician in the domain of obstetrics and gynecology and free to practice this profession; or (c) if the pregnancy has exceeded 14 weeks. An exception to the 14 weeks limit is provided by section (6) of Article 201, which stipulates that performing an abortion is not an offense if done for therapeutic purposes by a certified doctor until 24 weeks of pregnancy, and even after the 24 weeks limit, if the abortion is needed for therapeutic purposes "in the interest of the mother or the fetus". If the woman did not consent to the abortion; if she was seriously injured by the procedure; or if she dies as a result of it, the penalties are increased - sections (2) and (3) of Article 201. If the acts are done by a doctor, apart from criminal punishment, the doctor is also prohibited from practicing the profession in the future - section (4) of Article 201. Section (7) of Article 201 stipulates that a pregnant woman who provokes her own abortion will not be punished.[1]

Abortion rates after 1989

Abortion statistics, according to the National Institute of Statistics for data between 1990 and 2010[27] and according to Eurostat for data between 2011 and 2018:[28][29][30]

| Year | Abortions | Per 1,000 women | Per 1,000 live-births |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 899,654 | 177.6 | 3,158.4 |

| 1991 | 866,934 | 153.8 | 3,156.6 |

| 1992 | 691,863 | 124.2 | 2,663.0 |

| 1993 | 585,761 | 104.0 | 2,348.4 |

| 1994 | 530,191 | 93.2 | 2,153.5 |

| 1995 | 502,840 | 87.5 | 2,129.5 |

| 1996 | 455,340 | 78.6 | 1,971.9 |

| 1997 | 346,468 | 59.5 | 1,465.6 |

| 1998 | 270,930 | 46.5 | 1,144.0 |

| 1999 | 259,266 | 44.6 | 1,107.5 |

| 2000 | 257,267 | 44.3 | 1,099.5 |

| 2001 | 253,426 | 43.6 | 1,153.3 |

| 2002 | 246,714 | 44.0 | 1,174.9 |

| 2003 | 223,914 | 39.9 | 1,056.5 |

| 2004 | 189,683 | 33.8 | 879.5 |

| 2005 | 162,087 | 29.0 | 735.1 |

| 2006 | 149,598 | 27.0 | 683.5 |

| 2007 | 136,647 | 24.8 | 638.1 |

| 2008 | 127,410 | 23.5 | 578.3 |

| 2009 | 115,457 | 21.3 | 520.9 |

| 2010 | 101,271 | 18.8 | 478.9 |

| 2011 | 103,383 | ||

| 2012 | 88,135 | ||

| 2013 | 86.432 | 14.9 | 458.3 |

| 2014 | 78,371 | 13.6 | 394.3 |

| 2015 | 70,885 | 12.4 | 350.9 |

| 2016 | 63,518 | 11.3 | 308.7 |

| 2017 | 56,238 | 10.1 | 267 |

| 2018 | 52,318 | 9.4 | 258 |

| 2019 | 47,492 | 8.6 | 237.8 |

| 2020 | 31,681 | 6.1 | 178.1 |

| 2021 | 29,066[31] | 5.6 | 161.5 |

| 2022 | 28,420[32] | 5.6 | 166.8 |

United Nations data puts the abortion rate at 21.3 abortions per 1000 women aged 15–44 years in 2010.[33] Romania has a high prevalence of abortion: in a 2007 survey 50% of women said they had undergone an abortion during their lifetime.[34]

Future effects of the communist abortion policy

Ceaușescu's demographic policies are feared of having serious effects in the future because of the low number of births in the 1990s and 2000s. In Romania, the generations born under Ceaușescu are very large (especially the late 1960s and the 1970s), while those born in the 1990s and 2000s are very small. This is expected to cause a serious demographic shock when the former generations retire, as there will not be sufficient young people to form the workforce and support the elderly.[35][36][37]

See also

- 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, a Romanian film about a pregnant student looking for an illegal abortion during the Ceaușescu regime.

- Romanian orphans

References

- ^ a b "Noul Cod Penal (2014)". Avocatura.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Abortion statistics of Romania up to 2004 Archived 2007-10-07 at the Wayback Machine. Johnstonsarchive.net, Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ Benavides, L. (2021, September 1). Activists Say Romania Has Been Quietly Phasing Out Abortion. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/09/01/1021714899/abortion-rights-romania-europe-women-health

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Systems, Indaco. "Codul Penal din 1864". Lege5.ro. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Systems, Indaco. "Codul Penal din 1936". Lege5.ro. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Kligman, Gail. "Political Demography: The Banning of Abortion in Ceausescu's Romania". In Ginsburg, Faye D.; Rapp, Rayna, eds. Conceiving the New World Order: The Global Politics of Reproduction. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995 :234-255. Unique Identifier : AIDSLINE KIE/49442.

- ^ a b c d e Scarlat, Scarlat (2005-05-17). ""Decrețeii": produsele unei epoci care a îmbolnăvit România ("Scions of the Decree": Products of an Era that Sickened Romania") - Arhiva noiembrie 2007 - HotNews.ro". www.hotnews.ro (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ Horga, Mihai; Gerdts, Caitlin; Potts, Malcolm (1 January 2013). "The remarkable story of Romanian women9s struggle to manage their fertility". J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 39 (1): 2–4. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100498. PMID 23296845. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Kligman, Gail. The Politics of Duplicity: Controlling Reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998.

- ^ a b Steavenson, Wendell (10 December 2014). "Ceausescu's children". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Imaginea şi rolul femeii în perioada comunistă". Historia.ro. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Romania's Street Children". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Europe - What happened to Romania's orphans?". news.bbc.co.uk. 8 July 2005. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Adriana Mihaela Soaita. "Overcrowding and 'under-occupancy' in Romania : a case study of housing inequality". Research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "ABORTION POLICY" (DOC). Un.org. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Povestea de groază din spatele "afacerii decreţeilor" comunişti. Numărul terifiant al româncelor moarte din cauza avorturilor ratate în perioada 1966-1989". Adevarul.ro. 27 May 2016. Archived from the original on 26 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Decreţeii – generaţia copiilor născuţi de frica morţii". Descopera.ro. 26 November 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Kligman, Gail (2008). The politics of duplicity: controlling reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania (Nachdr. ed.). Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21075-2.

- ^ "Viata intr-o cutie de chibrituri". Evz.ro. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Kligman, Gail (2008). The politics of duplicity: controlling reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania (Nachdr. ed.). Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21075-2.

- ^ decrețel Archived 2009-05-19 at the Wayback Machine in the 123Urban dictionary

- ^ Kligman, Gail (2008). The politics of duplicity: controlling reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania (Nachdr. ed.). Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21075-2.

- ^ "Proiectul legii anti-avort - un atentat împotriva femeilor şi al familiilor - Romania Libera". RomaniaLibera.ro. 9 April 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Gynuity Health Projects » List of Mifepristone Approval". Gynuity.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-26. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Worrell, Marc. "Romania". Women on Waves. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ [1] [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Legally induced abortions by mother's age". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Abortion indicators". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "2021 Romanian Statistical Yearbook" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- ^ https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/anuarul_statistic_al_romaniei_carte-ed.2022.pdf

- ^ https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/anuarul_statistic_al_romaniei_carte_ed_2023-en.pdf

- ^ "World Abortion Policies 2013". United Nations. 2013. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ "AVORTUL ÎNTRE DREPT CÂŞTIGAT, RESPINGERE MORALĂ ŞI PRACTICĂ LARG RĂSPÂNDITĂ" (PDF). Fundatia.ro. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Ce se va intampla cand vor iesi la pensie "decreteii", cei 1,7 milioane de romani care sustin economia? - Ziarul Financiar". Zf.ro. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Pensiile "decreţeilor" sunt o bombă cu ceas. Statul le poate plăti 15% din salariu la bătrâneţe - Ziarul Financiar". Zf.ro. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "APOCALIPSA pensiilor vine după 2030. Cum poate fi DEZAMORSATĂ BOMBA SOCIALA produsă de Ceaușescu printr-un DECRET ORIBIL". Evz.ro. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.