History of Worthing

Worthing is a large seaside town in Sussex, England in the United Kingdom. The history of the area begins in Prehistoric times and the present importance of the town dates from the 19th century.

Prehistory

Stone Age

Within 7 miles (11 km) of Worthing's town centre lie four of Britain's 14 confirmed Neolithic flint mines.[1] The oldest of these mines, at Church Hill in Findon, may be one of the earliest known mines in Britain.[2] Thought to date from the 5th millennium BC and 4th millennium BC, these mines represent some of the oldest mines in Europe, if not the world and predate the great neolithic sites of Stonehenge and Avebury. In the Neolithic period, the South Downs above Worthing was one of Britain's largest and most important flint-mining centres.[3] These extensive flint mines which include the considerable mines at Cissbury are in many ways comparable to the vast flint mines of Spiennes in Belgium which have been given World Heritage Site status.

The secondary southern escarpment of the South Downs close to Worthing, south of the main ridge of the Downs (formed by hills such as Steep Down, Cissbury, Church Hill and Harrow Hill) is most visible west of the River Adur and it is this flint which is especially hard and durable and hence valuable in Neolithic times.[4] Flint from these early mines played a significant role in enabling the "Neolithic Revolution" to take place across southern Britain, gradually replacing the nomadic hunter-gatherer way of life of the mesolithic period with the settled agricultural way of life of the neolithic period as the extensive wildwood forest that covered much of Britain began to be felled.[5] There is evidence that flint from the mines around Worthing was traded across southern Britain, particularly to the populous areas on the Wessex downland.[4]

The flint mines were at Harrow Hill in Patching (mined from 4250 BC to 3500 BC), Blackpatch Hill in Clapham (4350 BC to 3500 BC), Church Hill in Findon (4500 BC to 3750 BC)—[6] all outside the present borough of Worthing—and Cissbury, which is within the borough and which had between 100 and 200 mineshafts, making it Britain's second largest after Grimes Graves in Norfolk.[3][7] Tolmere, near Findon, has been identified as a probable site.[1] Sites at High Salvington and Mount Carvey, within the borough, and at nearby Myrtlegrove and Roger's Farm in Patching and Findon, have all been identified as possible, but cannot be confirmed because of plough disturbance.[1] The flints would have been used to make tools such as axes, scrapers and arrow heads. At Harrow Hill, dozens of ox skulls have been found, suggesting ritual slaughter—possibly each autumn, as many animals would not have survived the winter. In the mineshafts, drawings of an Earth Spirit and phalluses may have been used to protect the fertility of the mines.[4] At Blackpatch, remains of what appear to be miners' huts have been found. At Cissbury, there were more than 270 pits, and the flint was used locally and exported—possibly as far as the eastern Mediterranean. Some shafts extended up to 75 feet (23 m) below the surface.[8] Four engravings, of a bull and deer, have been found in a shaft of one of the Cissbury flint mines. This is significant as few pieces of representational art survive from the British Neolithic period.[6]

For much of the neolithic period of the Stone Age, it is likely that the Worthing area was at the borders of territory of two tribes, one based at the causewayed enclosure at Whitehawk Camp (in modern Brighton) and one centred on the causwayed enclosure at the Trundle (near modern Chichester). However the apparent absence of settlement in the area at this time and other evidence from the mines themselves adds to speculation that the mines were special places, with sacred areas surrounding the mines. Such an area may have existed between the rivers Adur and Arun where the mines were situated on a block of downland that does not appear to contain any other contemporary monument.[9] The high status of this area, compared to the rest of Sussex, may have continued on into the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Henges seem to have existed on the Downs near Worthing at Blackpatch, Church Hill, Cissbury and also at Cock Hill, midway between the neolithic mining areas of Harrow Hill and Blackpatch.[6] At Cock Hill lies a henge dating from the late neolithic period, 48 metres in diameter, roughly circular, with a single entrance to the south-east. Various round barrows have been found on the Downs near Worthing close to Blackpatch and Church Hill.[6]

Neolithic axes from the mines have been found away from the Downs in various locations across the modern town of Worthing including at Homefield Park, Heene Road, Broadwater, Pond Lane and Seldens Way. A site near the summit of West Hill in High Salvington, between Honeysuckle Lane and the covered reservoir, has been identified as the possible location of neolithic huts, possibly used by flint miners.[10]

Bronze Age

Several Bronze Age barrows have been found within the modern borough of Worthing, close to Cissbury on the Downs. The enclosures at Highdown Hill are believed to have been built at this time. Judging from the pottery and metalwork finds, Highdown Hill was a high status settlement at the time.[11] Various artefacts, including tools, metal and pottery have been found in the Worthing area. In 1877 a large collection of Bronze Age cakes, palstaves and axes was found in a Bronze Age pot near Ham Road in East Worthing.

Iron Age

The hill fort at Cissbury Ring dates from the middle Iron Age. Covering an extensive 60 acres (24 ha),[12] this is one of the largest Iron Age hill forts in Britain and indeed Europe.

During the Iron Age and earlier, the area between the rivers Adur and Arun was a special area, with high status and ritual significance.[11] From the Bronze Age, Highdown Hill had special status and the enclosures at Chanctonbury and Harrow Hill may have been important sites of ritual performance.[11] In the middle Iron Age, Cissbury was built and in the late Iron Age, this sector of the downs housed the Lancing Down 'shrine'.[11]

In 1842 a boat made from a hollowed-out oak tree was found at low tide in the sand near to Heene Road. It was believed that the boat dated from the Iron Age.

Roman times

Roman coins, tiles and pottery have been discovered in several parts of the town. Several roads in the Worthing area date from the Roman era or earlier, including the Roman road from Noviomagus Reginorum (modern Chichester) to Novus Portus, (possibly modern Portslade near Brighton)[13] which ran through Durrington and Broadwater.

It is likely that several of Worthing's roads were laid out during this period in a grid form marking out a field system known as 'centuriation'.[14] Worthing's High Street lies at the south of a long straight trackway that stretches from high on the South Downs to the sea and northwards into the Weald. The track would have been used as a droveway (for transhumance) and can still be walked today along much of its length. Coming off the Downs it is now known as Charmandean Lane, which turns into a footpath known as the Quashetts, which becomes High Street and finally the Steyne before reaching the sea. The track would have touched the western shoreline of the 'broad water' that is the sea inlet from which Broadwater gets its name.[14] The inlet would have existed for centuries but disappeared in the 18th century. It is likely that Worthing's grid system would have been based on this ancient track.[14] The grid system would have been used to demarcate plots of land for fields and development.

The modern South Farm Road was once a track running north–south, parallel to the Quashetts path.[14] It lies exactly 20 actus (about 710 metres) from the Quashetts path. 100 actus (about 3,550 metres) to the west of the Quashetts track lies the remains of a track that is probably Celtic in origin, also running north–south, by Stanhope Lodge, now on Poplar Road in Durrington.[14] The track once marked the border between the parishes of Goring and Durrington. Today the line of this track marks the boundary between Clapham and Worthing. Another modern road that appears to be on the Roman grid system is Tarring Road (east–west),[14] the ancient boundary between Heene and Tarring. South of Tarring Road (and the Teville stream is would have run alongside), the boundaries in the grid seem to be 24 actus apart from each other.[14] The ancient boundary between Heene (later West Worthing) and Broadwater (later Worthing) lies 24 actus west of the Quashetts track. George V Avenue (north–south), the ancient boundary between Tarring (later West Worthing) and Goring lies 72 actus from the Quashetts track.

There is evidence of several buildings from the Roman era in Worthing. The town's Museum and Art Gallery is built on the site of a Roman farmhouse. A Roman settlement existed along the modern Brighton Road between Merton Road and Navarino Road. Remains of a Roman villa and bath house have been found on the site of Northbrook College's main Goring campus. A Roman milepost was found in modern Grand Avenue in West Worthing, possibly indicating another Roman road. A Roman cemetery existed between Chesswood Road and the railway line and burials dating from the early 4th century have also been found near Park Crescent. Roman pottery and coins have been found at Stonehurst Road, at land south of Ringmer Road in Tarring and on the Upper Brighton Road. Some Romano-British houses have been excavated in the Titnore Woods area of Durrington. Several small houses at the hill fort of Cissbury Ring on the Downs north of the town would have been in use during the Roman period.

Just beyond the boundaries of the modern town of Worthing, a Romano-British shrine existed at Muntham Court (now by the site of Worthing Crematorium). A Roman villa and bath-house also existed at Highdown and at nearby Angmering. The nationally important Patching hoard of Roman coins that was found in 1997 is the latest find of Roman coins found in Britain, probably deposited after 475 AD, well after the Roman departure from Britain around 410 AD.[15] The hoard can be found in the town's Museum and Art Gallery.

The Middle Ages

Anglo-Saxon times

Around 450, Highdown was being used as a cemetery by the South Saxons. Almost 100 graves were found, possibly of Saxon warriors who died in the Saxon invasion of the area.[16] Highdown continued to be used for some time for burials and cremations of Saxons. It is significant that Highdown was being used as a cemetery by pagan Saxons at the same time that Romano-British villa at nearby Northbrook, less than a mile away was still in use by local Celtic Christians. This suggests that Celtic Britons and Saxons were able to live side-by-side in relative harmony.[17][18] The Saxons settled nearby Goring and Sompting and by the 13th century the settlement, then known as Wortinge, was populated primarily by farmers and mackerel fishermen. The hamlet of Worthing was originally part of the larger parish of Broadwater. Other nearby villages to later become part of Worthing include Tarring, Salvington, Goring, Heene and Durrington, as well as small parts of the parishes of Findon and Sompting.

Droveways (transhumance trackways) that extend from Tarring, Broadwater and nearby Sompting to grazing areas in the Weald via Cissbury Ring and Buncton near Wiston are believed to date from this period or earlier.[4]

High medieval period

Following the Norman conquest, William de Braose gave the manor of Worthing (then known as Ordinges) to Robert le Sauvage, whose descendants held Worthing for around 200 years. Worthing is first mentioned in the Domesday Book as two separate hamlets, Ordinges and Mordinges, when it had a population of just 22. By 1218 the Ordinges had become known as Wurddingg.[19] The county of Sussex was divided into administrative divisions known as 'rapes'. The manor of Worthing, in common with most of the modern borough of Worthing, was part of the rape of Bramber. In the 13th century, the manor of Worthing was owned by Margaret de Gaddesden, a descendant of Robert le Sauvage. Margaret de Gaddesden later left her husband, John de Camoys, to live with Sir William Paynel, who she later married.[20] It is likely that as a consequence of leaving her first husband for another man she then gave the manor of Worthing to Easebourne Priory near Midhurst, while in 1332 Sir William gave the nearby manor of Cokeham to Hardham Priory near Pulborough. By giving away their property to the church it is likely that Margaret and Sir William were acting in fear of their souls as the medieval church taught damnation was likely.[14]

Worthing had a chapel throughout the high and late Middle Ages, although its location remains unknown.[21] First recorded in 1291, the chapel was in use for mass in 1410[22] and was still in use by the early 16th century. In private ownership by 1575, it had been demolished by 1635.[23]

In 1300 and again in 1493, Worthing is recorded as having a harbour, possibly in the estuary of the Teville stream.[24] Worthing harbour was a member of Shoreham Port in 1324.[24]

The modern period

Early modern

Worthing was owned by the Easebourne Priory until the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539. It then became the property of Anthony Browne, 1st Viscount Montagu, whose family held the manor of Worthing for over 200 years.

On his way across the Atlantic for the first time, William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, landed at Worthing from the Kent port of Deal with his ship, the Welcome, to pick up at least 16 people from Sussex.[25] On his return journey across the Atlantic in 1684, Penn again landed at Worthing as he travelled to his home in Warminghurst, about 10 miles (16 km) to the north of Worthing. Penn actually wrote Worden in some letters and in the beginning of an autobiography, which is how Worthing would have been pronounced by the people of Sussex at this time.[26]

It was in the late 18th century that Worthing began to attract visitors. John Luther, from London, started the trend, building a large lodging house around 1759[27] at the south end of High Street. In 1789, George Greville, 4th Earl of Warwick, bought the house and renamed it Warwick House.[28] With a warm climate and calm seas, it benefited from the Edwardian fashion for sea cures. Over the course of the next century Worthing became a fashionable resort on the circuit along with the towns of Bath, Brighton, Bognor Regis, Cheltenham and Margate.

19th century

Royal visits from Princess Amelia in 1798, Princess Charlotte in 1807 and Princess Augusta in 1829 did much to make the town popular. The Prince of Wales visited his youngest sister Princess Amelia in Worthing from nearby Brighton. In 1814, Queen Caroline visited Worthing on her way back to live in Brunswick in northern Germany.[citation needed] In addition, Queen Adelaide stayed in the town in 1849 and in 1861 Queen Marie Amelie of France stayed in the town when exiled from her country.

Notable visitors to the fashionable town of Worthing in the 19th century included novelist Ann Radcliffe,[29] the Duke of Northumberland in 1802, Henry Dundas in 1804, Jane Austen in 1805, Lord Byron in 1806,[30] the Duke of Cumberland in 1817, George Eliot in 1855,[31] Oscar Wilde in 1893 and 1894, who wrote his masterpiece The Importance of Being Earnest while staying in the town in 1894, and the future Emperor Maximilian of Mexico.

In 1803 Worthing's population was approximately 2,500 and the hamlet was given town status. Cross Lane was renamed Montague Street and went on to become one of the new town's key thoroughfares. A turnpike road was built around this time linking Worthing directly to Horsham and London for the first time.[24]

In the early 19th century, a wall was built separating the fashionable town of Worthing from Heene just to the west. The wall was built from the sea to the banks of the Teville Stream, which could only easily be crossed at one point – the bridge at the top of the High Street, close to the Anchor public house (today's Jack Horner). Since the Teville Stream flows east and south to the sea, this effectively gave the town just one point of entry and exit, allowing 'undesirables' to be kept out.

Worthing's first Anglican church, St Paul's, was built in 1812; previously, worshippers had to travel to the ancient parish church of Broadwater. Residential growth in the 19th century led to several other Anglican churches opening in the town centre: Christ Church was started in 1840[32] and survived a closure threat in 2006;[33] Arthur Blomfield's St Andrew's Church brought the controversial "High Church" form of worship to the town in the 1880s—its "Worthing Madonna" icon was particularly contentious;[34][35] and Holy Trinity church opened at the same time but with less dispute.[35][36]

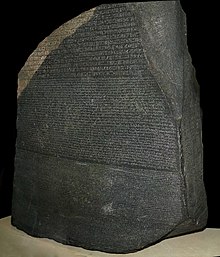

In 1814, polymath Thomas Young, who had a practice in Worthing, took a copy of the Rosetta Stone inscription to his summer home in Worthing to study.[37][38] Here he "made a number of original and insightful innovations"[39] in the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

In 1815, two infants' schools opened, mainly through the efforts of the Revd. W. Davison,[40] from the new St Paul's Church

In the early hours of February 22, 1832, a major smuggling foray took place when 300 kegs of contraband spirits[41] were unloaded at the beach opposite the Steyne. Excise officers chased a group of some two to three hundred men, one of Sussex's last smuggling gangs,[42] up the town's High Street and alleyways (known in the Sussex dialect as twittens) towards Broadwater. As the group slowed down to climb the gate guarding the bridge over the Teville Stream that would take them out of Worthing into open fields, horse-mounted excise officers opened fire at point-blank range on the crowd, who were armed only with wooden staves. They shot dead William Cowerson of Steyning and injured several others.[42] Civil unrest was feared and the military were brought into the town for two years to ensure peace was kept. As with many towns and villages in Sussex and Kent, close proximity to the Continent made the trade of smuggling a lucrative and popular business.

In 1845 the railway was extended from Shoreham to Worthing, linking the town by rail with London and the railway network.

On 25 November 1850, eleven local fishermen were drowned as they set out from the town's beach to save the crew of the barque the Lalla Rookh, a trading vessel of around 700 tons. The boat was in distress in a storm 3 miles (4.8 km) off the coast, and eleven fishermen set out on board a small ferry, the Britannia. The Britannia capsized, and a second boat was launched, returning with the news that the Britannia was lost with all lives. Soon afterwards the town's inhabitants subscribed for the town's first lifeboat.[43][44][45] The incident was widely reported at the time.[46][47]

In the 1880s, Worthing was the scene of several riots and violent incidents as the Salvation Army's work in the town aroused much anger among the local population. Objecting to the militant anti-drinking stance taken by the Salvation Army,[48] many formed a group known as the Skeleton Army that rioted in the town.

In 1890 the town received its royal charter and became the borough of Worthing. Worthing absorbed the neighbouring area of West Worthing and parish of Heene. The first meeting of the new Borough Council (replacing the Worthing Local Board and the West Worthing Commissioners) took place on 10 November 1890, when Worthing elected its first mayor, Alfred Cortis.

In 1893 an outbreak of typhoid fever caused 200 fatalities in the town, after 1,416 people caught the disease. The relatively young council took swift action, and by 1895 the town had a new drainage system.

20th century

The 20th century saw a continual expansion of the town, as it expanded to include local villages. In 1902 the borough of Worthing expanded to include parts of Broadwater and West Tarring. In 1929 the borough of Worthing expanded to include Goring and Durrington. And in 1933 the borough of Worthing expanded again to include the west of Sompting and the south of Findon.

Between 1908 and 1910, King Edward VII visited Worthing several times to stay at Beach House with the Loder family.

On 31 March 1930, Charles Bentinck Budd was elected to the Offington ward of the West Sussex County Council. Later that year, Budd, who lived at Greenville, Grove Road, was elected to the town council as the independent representative of Ham Ward in Broadwater.[49] At an election meeting on 16 October 1933, Budd revealed he was now a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). He was duly re-elected and the national press reported that Worthing was the first town in the country to elect a fascist councillor.[50] Street confrontations took place culminating on 9 October 1934 when anti-fascist protesters met outside a Blackshirt rally at the Pavilion Theatre in what became known as the Battle of South Street.[51]

Following Italy's invasion of Abyssinia in 1936, Emperor Haile Selassie and his family were forced out of Ethiopia to the United Kingdom. They spent their first six weeks in the UK at the Warnes Hotel, one of the town's top hotels at the time.

During World War II, a hole was blown through Worthing Pier to prevent it being used as a landing stage in the event of an invasion. Barbed wire was spread across the beach, which was also mined. Canadian soldiers stayed in several parts of the town, including the former site of the town's rugby club in Tarring[52] and at Park Crescent in the town centre. Courtlands, an impressive country house in the Goring area of the town was used as headquarters of the First Canadian Army.[53] In February 1944, the British Army's 4th Armoured Brigade set up headquarters in the Eardley Hotel by Splash Point. 200 tanks arrived and troops were billeted in and around Steyne Gardens. Historic Beach House was used by the Air Training Corps. During World War II, food supplies were scarce and rationed. The United States Army Air Forces began construction of a training centre on a 145-acre (0.59 km2) site north of the railway near Durrington station, however construction ended when the War finished.[54] The people of Timaru in New Zealand donated food parcels to the people of Worthing. After the war, the people of Worthing donated a stained glass window to the people of Timaru in thanks for their efforts.

Immediately post-war, Worthing expanded with the Maybridge estate, planned by Charles Cowles-Voysey. The redbrick housing estate used Prisoner of War labour, and was built between 1948 and 1956.

In the late 20th century many of the town's historic buildings were demolished by planners eager to 'modernise' the town. Notable losses included the town's Theatre Royal, the Old Town Hall, dating from 1834, medieval Offington Hall, the mansion at Charmandean, a medieval fig garden in Tarring and dozens of Victorian villas throughout the town.

In the late 20th century, Worthing had a significant motor industry. In 1979, Octav Botnar founded Datsun UK, later Nissan UK, in the West Durrington area of the town. In the 1970s and 1980s, Dutton Cars produced kit cars from their Worthing headquarters, and for a time was the largest manufacturer of kit cars in the world. The company went on to produce two models of amphibious car, that could be 'driven' across land and sea.[55] International Automotive Design (IAD) was one of the UK's major design houses for cars, producing prototypes for manufacturers such as Mazda, including the first Mazda MX-5. In 1994, the company was bought by Daewoo who continued to develop cars at their Worthing Technical Centre, including the Daewoo Nubira and the Daewoo Matiz plus trucks and vans, one of which became the LDV Maxus. In 2001, the Worthing centre was bought by TWR Racing which went out of business in 2003.[56]

21st century

The town's council approved Worthing Evolution, a Masterplan for the town's regeneration, in 2006 after extensive public consultation.

Since May 2006, environmentalist protesters have been tree sitting at Titnore Wood, in the Durrington area of the town. The action is in protest at plans to build houses and a road-widening scheme through ancient woodland on the edge of the town.

From February 2008, Worthing will host the reopened public inquiry into the proposed national park for the South Downs.[57]

In July 2009 Transition Town Worthing (TTW) was established to engage the Worthing community in responding to the twin challenges of climate change and the end of cheap oil, and encourage participation in projects to enable Worthing to become more self-reliant and sustainable.[58]

In the first decade of the 21st century, Worthing was one of the only towns in the UK to have had various illegal cannabis "cafés", all of which were subsequently closed. Chris Baldwin (a Legalise Cannabis Alliance activist) first opened one in a back room of his shop, "Bongchuffa", on Rowlands Road. It was named "The Quantum Leaf" and there was so much demand that he opened another called "Buddies", and simultaneously set up "The Herb Connection". Both cafés were subject to continual police raids. The first was shut when the landlord withdrew the lease for the property shortly followed by the second which closed due to police intercepting users on their way out of the property.

Another such establishment, operating in a less obvious, but still public manner was also opened and operated freely in Worthing for over two years, by a group not associated with the LCA and was continually raided. The site of this cafe was reduced to rubble within months of the last raid, and is now the site of modern flats.

See also

References

- ^ a b c "The Neolithic Flint Mines of Sussex: Britain's Earliest Monuments". Bournemouth University Centre for Archaeology, Anthropology & Heritage website. University of Bournemouth. 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Castleden.Neolithic Britain: new stone age sites of England, Scotland, and Wales. p.189.

- ^ a b Kerridge & Standing 2000, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Brandon 1998

- ^ "The Wildwood | Woodlands.co.uk". www.woodlands.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Russell 2002

- ^ Kerridge & Standing 2000, p. 8.

- ^ "Cissbury Ring". National Trust. 2009. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ Smart & Brandon 2007, p. 34, section by David McOmish and Peter Topping

- ^ Elleray 1998, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Hamilton & Gregory 2000

- ^ MacCurdy, George Grant (1 January 1905). "Review of Neolithic Dew-Ponds and Cattle-Ways". American Anthropologist. 7 (3): 529–531. doi:10.1525/aa.1905.7.3.02a00080. JSTOR 659048.

- ^ "Roman Britain – Organisation". Roman Britain. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kerridge & Standing 2005

- ^ "cnet Internet Coin Project – Hoards, The Patching Hoard". www.treasurerealm.com. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "VTT Explorers – Downs Time Line". Archived from the original on 20 September 2008.

- ^ White 1998, pp. 88–93

- ^ Martin Welch. Early Anglo-Saxon Sussex in Brandon. The South Saxons. pp. 23-25.

- ^ Stenton. The Place-names of Sussex. p.194. - Ordinges, Mordinges 1086, Wurddingg 1218, Wording(e) 1240, Worthing(e) 1244.

- ^ "Broadwater | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Holden, Paul (25 January 2010). "Historians search for Worthing's medieval chapel". The Argus. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Worthing: Churches". British History Online. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Harris, Roland B. (December 2009). "Worthing Historic Character Assessment Report" (PDF) (PDF). Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "Worthing – British History Online".

- ^ Hayes, Martin (11 September 2019). "William Penn in West Sussex". West Sussex Record Office. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Sheppard, Walter Lee Jr. (1970). Passengers and Ships Prior to 1684. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. p. 25.

- ^ History Archived 2008-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Elleray 1998, p. 139.

- ^ "The Life of Ann Radcliffe".

- ^ "Discover the delights of Worthing – Visit Worthing". Archived from the original on 7 May 2006.

- ^ "George Eliot – London Borough of Richmond upon Thames". Archived from the original on 1 December 2012.

- ^ Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 386.

- ^ "Historic church is facing closure". The Argus. Newsquest Media Group. 18 May 2006. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ^ Elleray 1977, §151.

- ^ a b Elleray 1998, p. 48.

- ^ Elleray 1977, §150.

- ^ "Archaeology: A clash of symbols". Nature Middle East. 29 February 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ^ Ray, John; J.D.Ray (2007). The Rosetta Stone and the Rebirth of Ancient Egypt. Profile Books Ltd. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-674-02493-9.

- ^ Dictionary Of National Biography

- ^ From: 'Worthing: Education', A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 1: Bramber Rape (Southern Part) (1980), pp. 125-28. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=18233. Date accessed: 21 August 2007.

- ^ "THIS IS FINDON VILLAGE – Smuggling in the 1800s in Findon Village, West Sussex. U.K." Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ a b Brandon, Peter (2006), Sussex ISBN 978-0-7090-6998-0

- ^ 'A Town's Pride, Rob Blann, published by Rob Blann 1990

- ^ Blann, Rob. "Worthing Lifeboat Town: Timeline". Worthing Lifeboat Town. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Maritime mystery comes to light". The Argus (Brighton). 7 July 2000. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Port of Launceston". The Argus (Melbourne). Vol. II, no. 737. Victoria, Australia. 31 March 1851. p. 2. Retrieved 27 January 2021 – via National Library of Australia. Note: Incorrect date of 2 December in this report.

- ^ "Maritime Intelligence". Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury. No. 251. Newcastle-upon-Tyne. 30 November 1850. p. 8.

- ^ "Worthing History 1851–1900 – Worthing.net".

- ^ "The notorious Charles Bentinck Budd and the British Union of Fascists". www.worthingherald.co.uk.

- ^ "Charles Bentinck Budd".

- ^ "Friend of the Nazis who fate left behind". The Argus. 23 January 2003. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "Worthing RFC". Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ "The History of Courtlands". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ Butler, Chris (2008). West Sussex Under Attack, Anti-Invasion Sites 1500–1990. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4171-9

- ^ Dutton Cars

- ^ "TWR hit by Arrows collapse". BBC News. 14 February 2003. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Defra, UK – Wildlife and Countryside – Landscape Protection – National Parks – South Downs". Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ^ "Transition Town Worthing". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

Bibliography

- Body, Geoffrey (1984). Railways of the Southern Region. PSL Field Guides. Cambridge: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85059-664-9.

- Brandon, Peter (1998). The South Downs. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 978-1-86077-069-2.

- Brandon, Peter, ed. (1978). The South Saxons. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 978-0-85033-240-7.

- Castleden, Rodney (1992). Neolithic Britain: new stone age sites of England, Scotland, and Wales. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05845-2.

- Elleray, D. Robert (1977). Worthing: a Pictorial History. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 978-0-85033-263-6.

- Elleray, D. Robert (1998). A Millennium Encyclopaedia of Worthing History. Worthing: Optimus Books. ISBN 978-0-9533132-0-4.

- Elleray, D. Robert (1999). St Paul's Church, Worthing: a History and Description. Worthing: Optimus Books. ISBN 978-0-9533132-1-1.

- Hamilton, Sue; Gregory, Kate (2000). "Updating the Sussex Iron Age". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 138: 57–74. doi:10.5284/1085799.

- Kerridge, Ronald; Standing, Michael (2000). Worthing: From Saxon Settlement to Seaside Town. Worthing: Optimus Books. ISBN 978-0-9533132-4-2.

- Kerridge, Ronald; Standing, Michael (2005). Worthing. Teffont: The Francis Frith Collection. ISBN 978-1-85937-995-0.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1983). South Coast Railways – Brighton to Worthing. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-03-1.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). The Buildings of England: Sussex. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-071028-1.

- Russell, Miles (2002). Prehistoric Sussex. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-1964-0.

- Smart, Gerald; Brandon, Peter (2007). The Future of the South Downs. Chichester: Packard Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85341-137-3.

- Stenton, Frank; A.Mawer (1930). The place-names of Sussex, Volume 6. Cambridge University Press.

- White, Sally (1998). "The Patching hoard" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 42: 88–93. doi:10.1080/00766097.1998.11735619.

- White, Sally (2000). Worthing Past. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 978-1-86077-146-0.