History of Nigeria

The history of Nigeria can be traced to the earliest inhabitants whose date remains at least 13,000 BC through the early civilizations such as the Nok culture which began around 1500 BC. Numerous ancient African civilizations settled in the region that is known today as Nigeria, such as the Kingdom of Nri,[1] the Benin Kingdom,[2] and the Oyo Empire.[3] Islam reached Nigeria through the Bornu Empire between (1068 AD) and Hausa Kingdom during the 11th century,[4][5][6][7] while Christianity came to Nigeria in the 15th century through Augustinian and Capuchin monks from Portugal to the Kingdom of Warri.[8] The Songhai Empire also occupied part of the region.[9] Through contact with Europeans, early harbour towns such as Calabar, Badagry[10][11] and Bonny emerged along the coast after 1480, which did business in the transatlantic slave trade, among other things. Conflicts in the hinterland, such as the civil war in the Oyo Empire, meant that new enslaved people were constantly being "supplied".

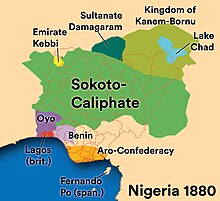

After 1804, Usman dan Fodio unified an immense territory in his jihad against the superior but quarrelling Hausa states of the north, which was stabilised by his successors as the "Caliphate of Sokoto".

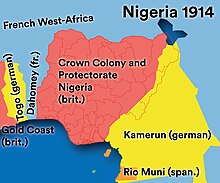

In its initial endeavour to stop the slave trade in West Africa, the United Kingdom gradually expanded its sphere of influence after 1851, starting from the tiny island of Lagos (3 km2) and the port city of Calabar. The British followed expansive trading companies such as the RNC and missionaries such as Mary Slessor, who advanced into the hinterland, preached and founded missionary schools, but also took action against local customs such as the religiously induced killing of twins or servants of deceased village elders and against the Trial by ordeal as a means of establishing the legal truth. At the Berlin Congo Conference in 1885, the European powers demarcated their spheres of interest in Africa without regard to ethnic or linguistic boundaries and without giving those affected a say. Thereafter, the British made increasing advances in the Niger region, which they had negotiated in Berlin, and ultimately defeated the Sokoto Caliphate. From 1903, Great Britain controlled almost the entire present-day territory of Nigeria, which was united under a single administration in 1914 (in 1919, a border strip of the former German colony of Cameroon was added to the territory of Nigeria).

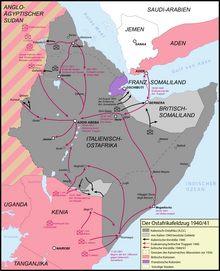

Under the British colonial administration, purchasing cartels (of companies such as Unilever, Nestlé and Cadbury) kept the prices of cocoa, palm oil and peanuts artificially low, thereby damaging Nigerian agriculture, but on the other hand ports and an extensive railway network were also built. Newspapers, political parties, trade unions and higher education institutions were established - rather against the wishes of the colonial rulers in order to control the oversized colony. In the East African campaign of 1941, Nigerian regiments achieved the first major success against the Axis powers with the fastest military advance in history at the time.[12] In 1956, oil fields were discovered in Nigeria. Since then, vandalism, oil theft and illegal, unprofessional refining by local residents have caused the contamination of the Niger Delta with crude and heavy oil, particularly around disused exploratory boreholes.[13][14][15]

Nigeria became independent in 1960. From 1967 to 1970, the "Biafra War" raged in the south-east - one of the worst humanitarian disasters of modern times. After three decades mostly of increasingly restrictive military dictatorships, Nigeria became a democratic federal republic based on the US model in 1999. Quadrennial elections are criticised as "non-transparent".[16] Nevertheless, changes of power in the presidential villa at Aso Rock took place peacefully in 2007, 2010, 2015 and 2023, making Nigeria one of the few stable democracies in the region - despite its shortcomings. The Boko Haram revolt of 2014, which received much attention in the West, fell apart due to infighting and the united approach of Nigeria and its neighbours. The spread of the Ebola epidemic to the slums of Lagos in the same year was prevented by professional crisis management.[17] Recent years have seen the rise of the Nigerian music and film industry and success in software programming with five out of seven African tech unicorns.[18] With large new refineries, the country attempts since January 2024 to process the extracted domestic crude oil on its own and in a professional manner in the future (meaning without heavy oil as a waste product).[19][20]

The biggest security problem is the numerous kidnappings, 38% of Nigerians personally know a kidnap victim.[21] Due to the abrupt economic turnaround in 2023, 64% of Nigerians are hungry or cannot finance basic needs.[22] 78% rate the work of President Tinubu as ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’.[22]

Prehistory

Acheulean tool-using archaic humans may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP (Middle Pleistocene).[23]

By at least 61,000 BP, Middle Stone Age West Africans may have begun to migrate south of the West Sudanian savanna, and, by at least 25,000 BP, may have begun to dwell near the coast of West Africa.[24]

An excessively dry Ogolian period occurred, spanning from 20,000 BP to 12,000 BP.[25] By 15,000 BP, the number of settlements made by Middle Stone Age West Africans decreased as there was an increase in humid conditions, expansion of the West African forest, and increase in the number of settlements made by Late Stone Age West African hunter-gatherers.[26] Iwo Eleru people persisted at Iwo Eleru, in Nigeria, as late as 13,000 BP.[27]

Macrolith-using late Middle Stone Age peoples, who dwelled in Central Africa, to western Central Africa, to West Africa, were displaced by microlith-using Late Stone Age Africans as they migrated from Central Africa into West Africa.[28] After having persisted as late as 1000 BP,[29] or some period of time after 1500 AD,[30] remaining West African hunter-gatherers were ultimately acculturated and admixed into the larger groups of West African agriculturalists.[29]

The Dufuna canoe, a dugout canoe found in Yobe State in northeastern Nigeria has been dated to around 6300 BC,[31] making it the oldest known boat in Africa, and the second oldest worldwide.[31][32]

Iron Age

Archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in what is now Igboland: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[33][34] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[34][35] Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture between the 9th century BC and 550 BC.[36][37] More recently, Bandama and Babalola (2023) have indicated that iron metallurgical development occurred 2631 BC – 2458 BC at Lejja, in Nigeria.[38]

Daima, an archaeological tell site located near Lake Chad in Borno State, has a history of human occupation spanning approximately 1800 years, from 550 BC to 1150 AD. The sequence of occupation is divided into three phases: Daima I (800 BC—500 AD) represents an occupation of a people without metalwork; Daima II (500 BC—800 AD) represents the earliest iron-using people of the site; and Daima III (800 BC—1100/1300 AD) a more "advanced" iron-using people.[39]

Nok culture

Nok culture may have emerged in 1500 BC and continued to persist until 1 BC.[40] Nok people developed terracotta sculptures through large-scale economic production,[41] as part of a complex funerary culture.[42] Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture between the 9th century BC and 550 BC.[36][37] As each share cultural and artistic similarity with the Nok culture, the Niger-Congo-speaking Yoruba, Jukun, or Dakakari peoples may be descendants of the Nok peoples.[43] Based on stylistic similarities with the Nok terracottas, the bronze figurines of the Yoruba Ife Empire and the Bini kingdom of Benin may also be continuations of the traditions of the earlier Nok culture.[44]

Igbo-Ukwu

Igbo-Ukwu, an archaeological site in southeastern Nigeria, gained prominence for its remarkable discoveries dating back to the 9th century AD. The excavations revealed a complex of burial sites containing a stunning array of bronze and copper artifacts, showcasing advanced metalworking skills. Among the findings were intricately crafted ceremonial vessels, ornaments, and tools, challenging previous assumptions about the technological and artistic sophistication of ancient sub-Saharan Africa. The artifacts highlight a sophisticated society with a high level of craftsmanship and organizational complexity, providing crucial insights into the rich cultural traditions of the Igbo people.

The significance of Igbo-Ukwu lies in its contribution to reshaping the understanding of early African cultures. The site's discoveries not only demonstrated the Igbo people's ability to create aesthetically pleasing objects but also challenged misconceptions about the historical achievements of the continent. Igbo-Ukwu stands as a testament to the advanced metallurgical practices and cultural richness of the people who inhabited the region, leaving a lasting legacy in the study of African archaeology.

Roman expeditions to Nigeria (1st century AD)

Between 50 AD and 90 AD, Roman explorers undertook three expeditions to the area of present-day Nigeria. The reports of these expeditions confirm, among other things, the geologically already established extent of Lake Chad at that time and thus its drastic shrinkage in the past 2,000 years.

The expeditions were supported by legionaries and served mainly commercial purposes.[45]

One of the main goals of the explorations was the search for and extraction of gold, which was to be transported back to the Roman provinces on the Mediterranean coast by land with the help of camels.[46]

The Romans had at their disposal the memoirs of the ancient Carthaginian explorer Hanno the Navigator.[46] However, it is not known to what extent they were read, believed or found interesting by the Romans.

The three Roman explorations/expeditions in Nigeria were:

- The Flaccus expedition

- The Matiernus expedition[47]

- Possibly a commander of Legio III Augusta named Festus undertook an expedition in the direction of the Niger River.

Roman coins have been found in Nigeria. However, it is likely that all these coins were introduced at a much later date and there was not direct Roman traffic this far down the west coast. The coins are the only ancient European items found in Central Africa.[48]

Early states before 1500

Advance of Islam in the north, the 14 Hausa states

With the spread of Islam from the 7th century AD, the area became known as Sudan or Bilad Al Sudan (“Land of the Blacks”, Arabic: بلاد السودان). Around the eighth century, Arab documents mention that Muslims crossed the Sahara to West Africa for trade purposes.[49] Several factors contributed to the growth of the Muslim class in non-Muslim kingdoms. Islam facilitated long-distance trade by providing merchants with useful tools such as contract law,[50] credit (e.g. mudaraba) and information networks. Muslim merchants also played an important role as advisors and scribes. They had the ability to use letter-based writing (instead of hieroglyphics), which was helpful in the administration of kingdoms.[49] Arithmetic in a decimal system (Arabic numerals) was also introduced to West Africa through Islam.

A system of Hausa city-states had existed in northern Nigeria since the 11th century. These city-states were mainly subject to tribute to large empires such as Kanem on Lake Chad. In the 14th century, all the ruling elites of Hausaland were Muslims, although the majority of the population did not convert until the eighteenth century.

From 1400 onwards, Nigeria's first written documents with letters were produced in the north of the country. They were part of the Islamic missionary work and were written in Ajami - a script based on Arabic, but supplemented by special letters for local languages (Hausa, Fula, Yoruba).[51] The Hausa also began to write history. In the Kano Chronicle, the history of the Hausa state is traced back to 999 AD.

Northern kingdoms of the Sahel

After the collapse of Mali, a local leader named Sonni Ali (1464-1492) founded the Songhai Empire in the Middle Niger region and took control of the trans-Saharan trade. Sonni Ali conquered Timbuktu in 1468 and Djenné in 1473 and built his regime on trade revenues and cooperation with Muslim merchants. His successor Askia Muhammad Ture (1493-1528) made Islam the official religion, built mosques and brought Muslim scholars to Gao, including al-Maghili (d. 1504).[52]

Throughout the 16th century, much of northern Nigeria paid homage to the Songhai Empire in the west or the rival Borno Empire in the east.[53]

Kanem–Bornu Empire

Kanem became an empire in the Lake Chad Basin in the 13th century. The Mai (king) of Kanem and his court adopted Islam in the 11th century.[54]: 72–73 [55] The first ruler of Kanem was Saif and his dynasty, the Sayfawa, ruled the empire for a millennium (800 AD to 1846 AD).[54]: 74 The first Muslim ruler of Kanem was Mai Umme Jilmi (r. 1085-1097), who died on his way to Mecca in Egypt. Due to the growing influence of Kanem in North Africa and the territorial expansion it achieved in the 12th and 13th centuries, the empire became very well known in the Islamic world of the time.[54]: 75

The civil war that shattered Kanem in the second half of the 14th century led to the independence of Bornu.[55] The Sayfawa moved to Bornu. Mai Ali Ghaji (r. 1470-1508) established a large capital there called Birnin N'gazargamu. He carried out government reforms and ended the civil unrest. With a reinvigorated army, he extended Bornu's influence to the neighboring regions and demanded tribute from some Hausa states. He also re-established diplomatic and trade relations with North Africa. Ali's successors continued to rule Kanem and kept it as a province of Bornu until the 19th century.[54]: 77–78

The most prosperous period in the history of the empire was the reign of Idris Alauma (1571-1603). His troops carried out far-reaching campaigns: in the north from southern Libya to northern Niger; in the east from eastern Chad to northern Cameroon; in the south he put down the rebellion of a Marghi prince and in the west he subdued Kano. He also carried out administrative reforms. He replaced customary law with Shari'a law and appointed qadis (judges). He built several mosques, which were constructed from baked bricks instead of reeds. He also undertook the pilgrimage to Mecca and financed the construction of a hostel for the Bornu pilgrims there.[54]: 79–82

Borno's economy was dominated by the Trans-Sudanese slave trade and the desert trade in salt and livestock. The court and mosques of Borno retained a reputation as centers of Islamic culture and scholarship.[56]

Development and formation of Ife

Archaeological evidence points to settlements in Ile-Ife dating back as early as the 10th to 6th century BCE. The city gradually transitioned into a more urban center around the 4th to 7th centuries CE. By the 8th century, a powerful city-state had formed, laying the foundation for the eventual rise of the Ife Empire (circa 1200-1420). Under figures like the Now defied figures such as Oduduwa, revered as the first divine king of the Yoruba, the Ife Empire grew. Ile-Ife, its capital, rose to prominence, its influence extending across a vast area of what is now southwestern Nigeria.[57]

The period between 1200 and 1400 is often referred to as the "golden age" of Ile-Ife, marked by exceptional artistic production, economic prosperity, and urban development. The Ife Empire's strategic location facilitated its participation in extensive trade networks that spanned West Africa. Of note is the evidence of a thriving glass bead industry in Ile-Ife. Archaeological excavations have unearthed numerous glass beads, indicating local production and pointing to the existence of specialized knowledge and technology. These beads, particularly the dichroic beads known for their iridescent qualities, were highly sought-after trade items, found as far afield as the Sahel region, demonstrating the far-reaching commercial connections of the Ife Empire.[58]

The wealth generated through trade fueled the remarkable urban development witnessed in Ile-Ife. Archaeological evidence points to a well-planned city with impressive infrastructure, including paved roads and sophisticated drainage systems, a distinctive feature of Ife urban planning was the use of potsherd pavements. These pavements, created using fragments of broken pottery. The Ife Empire declined around the 15th century.[58]

Oyo and Benin

During the 15th century, Oyo and Benin surpassed Ife as political and economic powers, although Ife preserved its status as a religious center. Respect for the priestly functions of the ooni of Ife was a crucial factor in the evolution of Yoruba culture. The Ife model of government was adapted at Oyo, where a member of its ruling dynasty controlled several smaller city-states. A state council (the Oyo Mesi) named the Alaafin (king) and acted as a check on his authority. Their capital city was situated about 100 km north of present-day Oyo. Unlike the forest-bound Yoruba kingdoms, Oyo was in the savanna and drew its military strength from its cavalry forces, which established hegemony over the adjacent Nupe and the Borgu kingdoms and thereby developed trade routes farther to the north.

The Benin Empire (1440–1897; called Bini by locals) was a pre-colonial African state in what is now modern Nigeria. It should not be confused with the modern-day country called Benin, formerly called Dahomey.[59]

The Igala are an ethnic group of Nigeria. Their homeland, the former Igala Kingdom, is an approximately triangular area of about 14,000 km2 (5,400 sq mi) in the angle formed by the Benue and Niger rivers. The area was formerly the Igala Division of Kabba province and is now part of Kogi State. The capital is Idah in Kogi state. Igala people are majorly found in Kogi state. They can be found in Idah, Igalamela/Odolu, Ajaka, Ofu, Olamaboro, Dekina, Bassa, Ankpa, omala, Lokoja, Ibaji, Ajaokuta, Lokoja and kotonkarfe Local government all in Kogi state. Other states where Igalas can be found are Anambra, Delta and Benue states.

The royal stool of Olu of Warri was founded by an Igala prince.

Yoruba

Historically, the Yoruba people have been the dominant group on the west bank of the Niger. Their nearest linguistic relatives are the Igala who live on the opposite side of the Niger's divergence from the Benue, and from whom they are believed to have split about 2,000 years ago. The Yoruba were organized in mostly patrilineal groups that occupied village communities and subsisted on agriculture. From approximately the 8th century, adjacent village compounds called ilé coalesced into numerous territorial city-states in which clan loyalties became subordinate to dynastic chieftains.[61] Urbanisation was accompanied by high levels of artistic achievement, particularly in terracotta and ivory sculpture and in the sophisticated metal casting produced at Ife.

The Yoruba are especially known for the Oyo Empire that dominated the region. The Oyo Empire held supremacy over other Yoruba nations like the Egba Kingdom, Awori Kingdom, and the Egbado. In its prime, they also dominated the Kingdom of Dahomey (now located in the modern day Republic of Benin).[62]

The Yoruba pay tribute to a pantheon composed of a Supreme Deity, Olorun and the Orisha.[63] The Olorun is now called God in the Yoruba language. There are 400 deities called Orisha who perform various tasks.[64] According to the Yoruba, Oduduwa is regarded as the ancestor of the Yoruba kings. According to one of the various myths about him, he founded Ife and dispatched his sons and daughters to establish similar kingdoms in other parts of what is today known as Yorubaland. The Yorubaland now consists of different tribes from different states which are located in the Southwestern part of the country, states like Lagos State, Oyo State, Ondo State, Osun State, Ekiti State and Ogun State, among others.[65]

Igbo Kingdoms

Nri Kingdom

The Kingdom of Nri is considered to be the foundation of Igbo culture and the oldest Kingdom in Nigeria.[66] Nri and Aguleri, where the Igbo creation myth originates, are in the territory of the Umueri clan, who trace their lineages back to the patriarchal king-figure, Eri.[67] Eri's origins are unclear, though he has been described as a "sky being" sent by Chukwu (God).[67][68] He has been characterized as having first given societal order to the people of Anambra.[68]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Nri hegemony in Igboland may go back as far as the 9th century,[69] and royal burials have been unearthed dating to at least the 10th century. Eri, the god-like founder of Nri, is believed to have settled in the region around 948 with other related Igbo cultures following in the 13th century.[70] The first Eze Nri (King of Nri), Ìfikuánim, followed directly after him. According to Igbo oral tradition, his reign started in 1043.[71] At least one historian puts Ìfikuánim's reign much later, around 1225.[72]

Each king traces his origin back to the founding ancestor, Eri. Each king is a ritual reproduction of Eri. The initiation rite of a new king shows that the ritual process of becoming Ezenri (Nri priest-king) follows closely the path traced by the hero in establishing the Nri kingdom.

— E. Elochukwu Uzukwu[68]

Nri and Aguleri and part of the Umueri clan, a cluster of Igbo village groups which traces its origins to a sky being called Eri and significantly, includes (from the viewpoint of its Igbo members) the neighbouring kingdom of Igala.

— Elizabeth Allo Isichei[73]

The Kingdom of Nri was a religio-polity, a sort of theocratic state, that developed in the central heartland of the Igbo region.[70] The Nri had a taboo symbolic code with six types. These included human (such as the birth of twins),[74] animal (such as killing or eating of pythons),[75] object, temporal, behavioral, speech and place taboos.[76] The rules regarding these taboos were used to educate and govern Nri's subjects. This meant that, while certain Igbo may have lived under different formal administrations, all followers of the Igbo religion had to abide by the rules of the faith and obey its representative on earth, the Eze Nri.[75][76]

With the decline of Nri kingdom in the 15th to 17th centuries, several states once under their influence, became powerful economic oracular oligarchies and large commercial states that dominated Igboland. The neighboring Awka city-state rose in power as a result of their powerful Agbala oracle and metalworking expertise. The Onitsha Kingdom, which was originally inhabited by Igbos from east of the Niger, was founded in the 16th century by migrants from Anioma (Western Igboland). Later groups like the Igala traders from the hinterland settled in Onitsha in the 18th century. Kingdoms west of the River Niger like Aboh (Abo), which was significantly populated by Igbos among other tribes, dominated trade along the lower River Niger area from the 17th century until European explorations into the Niger delta. The Umunoha state in the Owerri area used the Igwe ka Ala oracle at their advantage. However, the Cross River Igbo state like the Aro had the greatest influence in Igboland and adjacent areas after the decline of Nri.[77][78]

The Arochukwu kingdom emerged after the Aro-Ibibio Wars from 1630 to 1720, and went on to form the Aro Confederacy which economically dominated Eastern Nigerian hinterland. The source of the Aro Confederacy's economic dominance was based on the judicial oracle of Ibini Ukpabi ("Long Juju") and their military forces which included powerful allies such as Ohafia, Abam, Ezza, and other related neighboring states. The Abiriba and Aro are Brothers whose migration is traced to the Ekpa Kingdom, East of Cross River, their exact take of location was at Ekpa (Mkpa) east of the Cross River. They crossed the river to Urupkam (Usukpam) west of the Cross River and founded two settlements: Ena Uda and Ena Ofia in present-day Erai. Aro and Abiriba cooperated to become a powerful economic force.[79]

The Igbo-Igala Wars were a series of conflicts between the Igbo people and the Igala people in pre-colonial Nigeria. The wars occurred in the 18th and 19th centuries and were primarily driven by territorial disputes, competition for resources, and political power struggles between the two ethnic groups. The Igbo and Igala engaged in military confrontations, with both sides vying for control over strategic territories. These wars were part of the complex dynamics and inter-ethnic relations that characterized the region during that historical period. The outcomes of specific battles and the overall impact of the Igbo-Igala Wars varied, and the conflicts eventually contributed to shaping the socio-political landscape of the region.

Igbo gods were numerous, but their relationship to one another and human beings was essentially egalitarian, reflecting Igbo society as a whole. A number of oracles and local cults attracted devotees while the central deity, the earth mother and fertility figure Ala, was venerated at shrines throughout Igboland.

The Kingdom of Benin had influence on the western Igbo, who adopted many of the political structures familiar to the Yoruba-Benin region, but Asaba and its immediate neighbours, such as Ibusa, Ogwashi-Ukwu, Okpanam, Issele-Azagba and Issele-Ukwu, were much closer to the Kingdom of Nri. Ofega was the queen for the Onitsha Igbo.

Akwa Akpa

The modern city of Calabar was founded in 1786 by Efik families who had left Creek Town, farther up the Calabar river, settling on the east bank in a position where they were able to dominate traffic with European vessels that anchored in the river, and soon becoming the most powerful in the region extending from now Calabar down to Bakassi in the East and Oron Nation in the West.[80] Akwa Akpa (named Calabar by the Spanish) became a center of the Atlantic slave trade, where African slaves were sold in exchange for European manufactured goods.[81] Igbo people formed the majority of enslaved Africans sold as slaves from Calabar, despite forming a minority among the ethnic groups in the region.[82] From 1725 until 1750, roughly 17,000 enslaved Africans were sold from Calabar to European slave traders; from 1772 to 1775, the number soared to over 62,000.[83]

With the suppression of the slave trade,[84] palm oil and palm kernels became the main exports. The chiefs of Akwa Akpa placed themselves under British protection in 1884.[85] From 1884 until 1906 Old Calabar was the headquarters of the Niger Coast Protectorate, after which Lagos became the main center.[85] Now called Calabar, the city remained an important port shipping ivory, timber, beeswax, and palm produce until 1916, when the railway terminus was opened at Port Harcourt, 145 km to the west.[86]

First contact with colonial powers, Nigeria as a "slave coast"

Trade in ivory, gold and slaves

The first encounters between the inhabitants of the coast and Europeans, the Portuguese, took place around 1472. The Portuguese began to trade extensively, particularly with the kingdom of Benin. The Portuguese traded European products, especially weapons, for ivory and palm oil and increasingly for slaves. The manillas that the Portuguese used to pay their Nigerian suppliers were melted down again in the Kingdom of Benin to create the bronze artworks that adorned the royal palace as a sign of affluence.[87]

In 1553, the first English expedition arrived in Benin. From then on, European merchant ships regularly anchored on the West African coast, albeit at a safe distance from the mainland due to the mosquitoes in the lagoons and the tropical diseases they spread. Locals came to these ships on barques and conducted their business.[88] The Europeans named the coasts of West Africa after the products that were of interest to them there. The "Ivory Coast" still exists today. The western coast of Nigeria became the slave coast. In contrast to the Gold Coast further west (today's Ghana), the Europeans did not establish any fortified bases here until the middle of the 19th century.

The harbour of Calabar on the historic Bay of Biafra became one of the largest slave trading centres in West Africa. Other important slave harbours in Nigeria were located in Badagry, Lagos in the Bay of Benin and Bonny Island.[88][89] Most of the enslaved people brought to these harbours were captured in raids and wars.[90] The most "prolific" slave-trading kingdoms were the Edo Empire of Benin in the south, the Oyo Empire in the south-west and the Aro Confederacy in the south-east.[88][89]

Caliphate of Sokoto (1804 to 1903)

In the north, the incessant fighting between the Hausa city-states and the decline of the Bornu Empire led to the Fulani gaining a foothold in the region. Originally, the Fulani mainly travelled with cattle through the semi-desert region of Sahel in northern Sudan, avoiding trade and mixing with the Sudanese peoples. At the beginning of the 19th century, Usman dan Fodio led a successful jihad against the Hausa kingdoms and founded the centralised caliphate of Sokoto. The empire, with Arabic as its official language, grew rapidly under his rule and that of his descendants, who sent invading armies in all directions. The vast landlocked empire linked the east with western Sudan and penetrated the south, conquering parts of the Oyo kingdom and advancing into the Yoruba heartland of Ibadan. The territory controlled by the empire included much of what is now northern and central Nigeria. The Sultan sent emirs to establish suzerainty over the conquered territories and to promote Islamic civilisation; the emirs in turn grew richer and more powerful through trade and slavery.

By the 1890s, the largest slave population in the world, about two million, was concentrated in the Sokoto Caliphate. Slaves were used on a large scale, especially in agriculture.[91] When the Sokoto Caliphate disintegrated into various European colonies in 1903, it was one of the largest pre-colonial African states.[92]

Expeditions along the Niger and in northern Nigeria

Around 1829, Hugh Clapperton's expedition to Europe made it known that and where the Niger flows into the Atlantic. (He himself did not survive the journey, but died of malaria and dysentery. His documents were published by his servant Richard Lander). After this, there were numerous privately funded forays into the interior, such as the Niger Expedition of 1841 (in which a large number of the European participants quickly died of tropical diseases and which is reported in the diary of fellow traveller Samuel Ajayi Crowther, mentioned again in the next chapter).[93][94]

Around 1850, the explorer Heinrich Barth travelled through northern Nigeria as part of a British expedition. Through his travels, Barth acquired special merits in the unprejudiced and respectful study of peoples and languages (he himself had the ability to learn African languages very quickly - he spoke and wrote Arabic fluently), as well as in African history. Barth also developed the hypothesis of a primeval wet phase in northern Africa.

British ban on the slave trade (from 1807)

Around 1750, British merchant ships shipped European goods to Africa, from there slaves to American plantations and products from there, such as tobacco, to Europe. However, from 1787 and increasingly from 1791, following reports of a slave revolt in Saint Domingue, the British Parliament debated the abolition of the slave trade.[95]

With the prohibition of the slave trade (not slavery) by Britain in 1807, British interest in Nigeria shifted to palm oil for use in soaps and as a lubricant for machinery. However, abolition in Britain was one-sided, and many other countries took its place.[96] European companies and smugglers continued to operate the Atlantic slave trade. The British West Africa Squadron attempted to intercept the smugglers at sea. The rescued slaves were taken to Freetown, a colony in West Africa originally founded by Lieutenant John Clarkson for the resettlement of slaves freed by Britain after the American Revolutionary War in North America.

British colonial rule

Crown Colony of Lagos (since 1861)

Britain's West Africa squadron was tenacious in concluding anti-slavery treaties with coastal chiefdoms along the West African coast from Sierra Leone through the Niger Delta to the south of the Congo.[97] However, the Nigerian coast proved difficult to control with its countless bays, meandering channels and rampant tropical diseases.[96] Badagry, Lagos, Bonny and Calabar therefore remained lively centres of the slave trade. The fight against the slave trade by the British plunged the kingdom of Oyo into a crisis that ultimately led to civil war within the Yoruba region. It became a constant source of prisoners of war for the slave markets.

The consulate era

In 1841, Oba Akitoye ascended the throne of Lagos and tried to put an end to the slave trade. Some Lagos merchants resisted the ban, deposed the king and replaced him with his brother Kosoko.[96] Britain intervened in this power struggle within the Lagos royalty by bombarding Lagos with the Royal Navy in 1851. The British thus replaced Kosoko with Akitoye again. In 1852, Akitoye and the British consul John Beecroft signed a treaty to free the slaves and grant the British permanent trade access to Lagos. However, Akitoye had difficulties implementing these resolutions. The situation therefore remained unsatisfactory for Britain.

The Royal Navy originally used the harbour of the island of Fernando Po (now Bioko, Equatorial Guinea) off Nigeria as a base of operations. In 1855, Spain claimed this harbour for itself. The Royal Navy therefore had to look for another naval base and chose the island of Lagos, which at 9 km2 was roughly the same size as the Orkney island of Papa Westray resp. five times the size of Coney Island or one seventh of Lower Manhattan and flooded several times per year, for this purpose.[96] King Akitoye had died in the meantime. His brother Kosoko then threatened to take back control of Lagos with the help of French colonial troops. The American Civil War, which centred on the issue of slavery, made the power struggle for Lagos particularly urgent. As a result, Lord Palmerston (British Prime Minister) made the decision that it was expedient "losing no time in assuming the formal protectorate of Lagos".[97] William McCoskry, the acting consul in Lagos, together with Commander Bedingfield, convened a meeting with King Dosunmu, Akitoye's successor, on board HMS Prometheus on 30 July 1861, at which the British intentions were explained. Dosunmu resisted the terms of the treaty, but under the threat of having Commander Bedingfield bombard Lagos, he relented and signed the Lagos Cession Treaty.[98]

Lagos, naval base and growing commercial centre

Lagos proved to be strategically useful and became a major trading centre as traders could count on the protection of the Royal Navy to protect them from pirates, for example.[96] British missionaries penetrated further inland. Brazilian freedmen settled in Lagos.

The British government introduced English laws in Lagos in 1862. There was the Court of Civil and Criminal Justice and the West African Court of Appeal. A Supreme Court was established in 1876. English common law, equity law and British law applied.[99]

Push into the hinterland

After its experiences in the American War of Independence, Great Britain had limited itself to maintaining strategically placed bases around the world - such as Lagos - and avoided colonising regions far from the coast. This changed in the 1860s, when European powers embarked on the "Scramble for Africa". Up until this point, European trade with the natives was conducted by ships that anchored off the coast and travelled on once the business was concluded. As tropical lagoons - unlike the open sea - offer favourable conditions for mosquitoes, which pass on tropical diseases, Europeans avoided going ashore. Because of the "sleeping sickness", West Africa was nicknamed "The white man's grave" until around 1850. The industrial production of quinine from the 1820s and its use as a prophylactic against malaria on a large scale changed the situation. The European naval powers were now able to establish permanent settlements in the tropics.

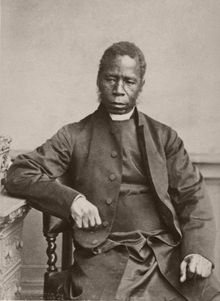

British missionaries penetrated the interior of the country. In south-eastern Nigeria, Hope Wadell and Mary Slessor fought against the customary killing of newborn twins, against the trial by ordeal in legal disputes and against the killing of the servants of deceased village elders (in order to be able to serve them in the afterlife) from 1845 onwards. Missionaries founded schools and enabled the careers of Eyo Ita, the first dark-skinned professor, and Nnamdi Azikiwe, the first Nigerian president, for example. In 1864, Samuel Ajayi Crowther became the first African bishop of the Anglican Church.[100]

The Royal Niger Company, the monopolist on the Niger

The first years of European colonialism in Africa were characterised by the Austrian school of economics and the marginal utility theory it advocated, according to which the value of products manufactured in Europe was higher in markets that were not yet saturated, such as Africa (marginal utility), and trade with colonies was therefore more profitable than in one's own country, for example. (The lower demand or purchasing power in the unsaturated market was not taken into account).

With the prospect of such high profits, various private trading companies promoted European influence in West Africa. One of them was the United Africa Company, founded by George Goldie in 1879, which was granted concessions for the entire area around the Niger Basin by the British government in 1886 under the name Royal Niger Company. The RNC marked out its territory as if it were a state in its own right and also negotiated treaties with the northern states, the Sokoto Caliphate, Nupe and Gwandu. It was also authorised to administer justice in its territories.[99]

The RNC faced competition from three other groups, two French trading companies and another British group. A price war ensued, in which the RNC emerged victorious because in France the main proponent of African colonisation, Léon Gambetta, had died in 1882 and in 1883 considerable subsidies for these "colonisation companies" were cancelled by the mother country.[101]

The RNC's monopoly enabled Britain to resist French and German demands for the internationalisation of trade on the Niger during negotiations at the Berlin Conference in 1884–1885. Goldie succeeded in having the region in which the RNC operated included in the British sphere of interest. British assurances that free trade in Niger would be respected were hollow words: the RNC's more than 400 contracts with local leaders obliged the natives to trade exclusively with or through the company's agents. High tariffs and royalties drove competing companies out of the territory.[102] When King Jaja of Opobo organised his own trading network and even began routing his own palm oil shipments to Britain, he was lured onto a British warship and exiled to St Vincent on charges of 'breach of treaty' and 'obstruction of trade'.[103]

The RNC, which traded mainly in liquor and arms along the Niger, soon gained a bad reputation. Originally a way for the colonial office to bring the region under British control at little cost, it proved ineffective in promoting peace and stability.[104] This was evident in the case of the Brass. They had no arable land of their own and traditionally lived from barter along the Niger. With the advent of the RCN, they had to pay license fees for imports and exports, which they could not afford. The Brass tried unsuccessfully to find alternative trade routes and began to starve. On December 29, 1894, they attacked the RNC headquarters in Akassa, looting much of the company's property and destroying the warehouses and machinery. They even kidnapped several of the company's employees, whom they later ritually ate as part of a spiritual ceremony,[104] which they hoped would protect them against the rampant smallpox epidemic. The RNC now demanded massive protection for its employees from the Colonial Office, which the latter was not prepared to do and which contradicted the above-mentioned goal of low expenditure. The Colonial Office, which had been under the imperialist leadership of Joseph Chamberlain since 1895, increasingly wondered whether it would not be better to place the monopolist's territory under direct colonial rule.[104]

After the Berlin Congo Conference

The Berlin Congo Conference of 1885 defined the spheres of interest of the European colonial powers in Africa - without regard to ethnic or cultural conditions and without the participation of the people in the affected regions. For example, the territory of the Yoruba and that of the Hausa was divided by the demarcation between the British and the French. One must even assume that this was intentional. After all, this fragmentation naturally made it easier for the colonial rulers to dominate the indigenous people.

Although this avoided wars between Europeans over these colonies, it encouraged military advances by Europeans in Africa - with devastating consequences for the "natives". This was due to the fact that a colonial power's demarcated territories were only valid if that colonial power actually brought the area under its control (rather than another power first).

Conquest of Ijebu (1892) and Oyo (1895)

The United Kingdom now took military action wherever British traders or missionaries saw their fields of activity restricted. In 1892, the British conquered the Ijebu Empire on the outskirts of Lagos, an empire that had previously seceded from the Oyo Empire and refused to engage in trade with the British.[105] Machine guns (of the Maxim type) were used for the first time. One Captain Lugard (see below) noted: "On the West Coast, in the 'Jebu' war, undertaken by Government, I have been told 'several thousands' were mowed down by the Maxim."[106]

In 1895, it was now not the British traders who called for military action, but missionaries in the Oyo Empire 50 km north of Lagos - which, even after its decline, was still one of the most powerful native states in present-day Nigeria and restricted the activities of the missionaries. The British bombed the capital Ibadan after Christian missionaries had brought their parishioners to safety. After the bombardment, the missionaries had a "fair" talk with the elector-king (Alaafin) of Ibadan and convinced him to submit to British protection.[107] Anglican Christianity became the "state religion" in Oyo.

The conquered territory was administered as the British "Protectorate of Yorubaland", while Lagos remained a colony. Residents of a colony were direct subjects of the Crown and could, for example, initiate legal proceedings against the colonial rulers. Residents of a protectorate did not have these rights.

The punitive expedition to the Kingdom of Benin in 1897

Benin was a slave-owning state 150 kilometres east of Lagos and was one of the four largest kingdoms in what is now Nigeria. As early as 1862, there were reports of human sacrifices being made in Benin in times of need. Consul Burton described the kingdom as "gratuitous barbarity which stinks of death".[108]

In 1892, Great Britain concluded a contract with King (Oba) Ovọnramwẹn of Benin for the supply of palm oil. The latter signed reluctantly and shortly afterwards made additional financial demands. In 1896, Vice-Consul Phillips travelled to Ovọnramwẹn with 18 officials, 180 porters and 60 local workers to renegotiate the contract. He sent a delegate ahead with gifts to announce his visit - but the king sent word that he did not wish to receive the visit for the time being[109] (King Ovọnramwẹn was aware of the fate of King Jaja of Opobo (see above), which could explain his lack of hospitality). Phillips nevertheless set off, but was ambushed, from which only two of his fellow travellers escaped alive, albeit seriously injured.[109]

In February 1897, a punitive expedition was set up under Admiral Rawson. The Colonial Office in London ruled: "It is imperative that a most severe lesson be given the Kings, Chiefs, and JuJu men of all surrounding countries, that white men cannot be killed with impunity..."[108] 5,000 British soldiers and sailors invaded the Kingdom of Benin, which barely defended itself but made the above-mentioned human sacrifices in its misery. The British forces encountered shocking scenes.[110]

The Kingdom of Benin was incorporated into the British dominion. The British burnt down the royal palace of Benin and looted the bronze sculptures there, which are now a World Heritage Site. These were later auctioned off in Europe to finance the punitive expedition.

The West African Frontier Force

In 1897, Captain Lugard, who had already established and stabilised British colonial rule in Malawi and Uganda, was commissioned to set up an indigenous Nigerian force to protect British interests in the hinterland of the colony of Lagos and Nigeria against French attacks. In August 1897, Lugard organised the West African Frontier Force and commanded it until the end of December 1899. By September 1898, Britain and France had already settled their colonial disputes in the Fashoda Crisis and concluded the Entente cordiale in 1904, thus depriving the WAFF of its original purpose[111] (However, the WAFF was to play a crucial role in the liberation of East Africa from (fascist) Italian rule during the Second World War in 1941. Colonel Lugard would significantly determine Nigeria's development over the next 22 years.

First railway line

The first railway line in West and Central Africa - between Lagos and Abeokuta - was opened in Nigeria in 1898[112] (However, it was followed shortly afterwards by the British colony of Gold Coast/Ghana (1901), the German colonies of Cameroon (1901) and Togo (1905) and the French colonies of Dahomey (1906) and Ivory Coast (1907)). Forced labour was also (or mainly) used in the construction work.[113] The staff of the railway company soon organised themselves and organised Nigeria's first strike in 1904.[114]

Southern Nigeria (since 1900)

The Royal Niger Company sells its land

Ten years after the "Scramble for Africa" - in the 1890s - it became increasingly clear that colonial rule in Africa was not a profitable endeavour and that the exploration and development of the continent, which had originally been initiated by the private sector, could only be continued through state-military measures and/or taxpayers' money. The above-mentioned marginal utility theory had given way to the theory of "shrinking markets", a term coined by the economic theorist Werner Sombart. According to this theory, colonies were supposedly a necessary measure for industrialised countries to maintain sales and food supplies. The theory was adopted by both "left-wing" theorists such as Bukharin and Luxemburg ("exploitation" of the colonies) and "right-wing" thinkers such as Rosenberg and Hitler ("Lebensraum").[115][116] The RNC's concession was revoked in 1899,[117] and on 1 January 1900 it ceded its territories to the British government for the sum of £865,000. The ceded territory was merged with the small Niger Coast Protectorate, which had been under British control since 1884, to form the Southern Nigeria Protectorate,[118] and the remaining RNC territory of around 1.3 million square kilometres became the Northern Nigeria Protectorate. 1,000 British soldiers were stationed in the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria, 2,500 in the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria and 700 in Lagos. The RNC was taken over by Lever Brothers in 1920 and became part of the Unilever Group in 1929. In 1939, the latter still controlled 80 per cent of Nigerian exports, mainly cocoa, palm oil and rubber.[119]

The south-east

Due to the complex coastline in the Niger Delta, there were no closed dominions in south-east Nigeria until 1900, but rather a conglomerate of city-states that focussed on trade along the coast and inland along the Niger and Benue rivers. These city-states, which were united in the "Aro Confederacy", had a religious centre in Arochukwu, the "Juju Oracle". The form of decision-making in the city-states can be described as "pre-democratic". In this region, which later became sadly known as "Biafra", feudal rule was just as difficult to enforce as British colonial rule. (The later Biafra War of 1966 to 1970 was, among other things, a conflict between the democratic instincts of the south-eastern Igbo population and the authoritarian structures in the rest of Nigeria). The British defeated the Aro Confederacy in the Anglo-Aro War (1901–1902) and spread their influence along the coast to the south-east as far as German Cameroon. However, control of the Niger Delta remained an unsolved problem both for the British colonial rulers and later for independent Nigeria. Pirates, marauders, self-proclaimed freedom fighters and (since 1957) oil thieves still find enough nooks and crannies in the confusing landscape and under the jungle canopy to evade police action.

After 1902

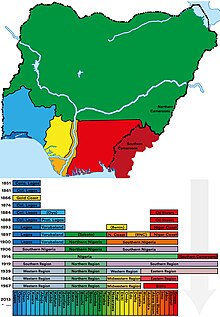

In 1906, the crown colony of Lagos was incorporated into the protectorate of Southern Nigeria.

In Lekki, near Lagos, the Nigerian Bitumen Corporation under businessman John Simon Bergheim discovered crude oil during test drilling in 1908. However, engineers were unable to prevent large quantities of water from being extracted as well. Oil production could therefore not be made profitable without additional investment. Bergheim's fatal car accident in 1912 put an end to further exploration of Nigeria's oil reserves for the time being.[120]

In 1909, coal deposits were discovered and extracted in the south-east of Nigeria, in Enugu[121] Two years later, this region, the Nti Kingdom, was placed directly under British colonial administration.[122][123]

Despite the consecration of Samuel Ajayi Crowther as a bishop - or perhaps because of it - European and North American churches refused to accept dark-skinned clergymen, while the mainly Protestant missionary work in southern Nigeria was quite successful. This led to countless evangelistic and Pentecostal free churches, which are still omnipresent in the south today.[124]

Nigeria's first trade union, the Nigeria Civil Service Union, was formed in 1912,[125] but would not be recognised until 1938, until which time its members were subjected to harassment.

Northern Nigeria (since 1900)

In 1900, Colonel Lugard was appointed High Commissioner of the newly created Protectorate of Northern Nigeria. He read the proclamation at Mount Patti in Lokoja that established the protectorate on 1 January 1900,[126] but at this time the part of northern Nigeria that was actually under British control was still small.[111]

North-east

In 1893, Rabih az-Zubayr, a Sudanese warlord, conquered the Kingdom of Bornu. The British recognised Rabih as "Sultan of Borno" until the French killed Rabih at the Battle of Kousséri on 22 April 1900. The colonial powers of Great Britain, France and Germany divided up his territory, with the British receiving what is now north-east Nigeria. They formally restituted the Borno Empire under British rule before the conquest in 1893 and appointed a scion of the ruling family of the time, Abubakar Garbai, as "Shehu" (Sheikh).

Northwest

In 1902, the British advanced north-westwards into the Sokoto Caliphate. In 1903, victory at the Battle of Kano gave the British a logistical advantage in pacifying the heartland of the Sokoto Caliphate and parts of the former Borno Empire. On 13 March 1903, the last vizier of the caliphate surrendered. By 1906, resistance to British rule had ended,[127] and there would be no more war within Nigeria's borders for the next 60 years. When Lugard resigned as commissioner in 1906, the entire region of present-day Nigeria was administered under British supervision.[111]

The Protectorate of Northern Nigeria, the ‘Indirect Rule’

After the British trauma of the siege of Khartoum, the colonial office favoured a more subtle approach in Islamic northern Nigeria. Lugard developed the concept of ‘Indirect Rule’, in which the colonial rulers left the traditional social structures intact. The fact that the Sokoto Caliphate of 1804 was a rule of the Fulani over the more numerous Hausa worked in his favour. By replacing the Fulani with the British, the new British rule in northern Nigeria could be implemented with minimal social upheaval.

The Sokoto Caliphate was formally allowed to continue and a new caliph, Attahiru II, was appointed in 1903. However, the sultan of the caliphate was now the governor of northern Nigeria, namely Lugard. Like his Fulani predecessors, he had the right to enact laws and appoint officials. Murray Last therefore refers to the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria as the ‘Colonial Caliphate’.[128]

The local regents remained the emirs (several hundred in a three-tier hierarchy). The emirs were appointed by so-called ‘kingmakers’, whereby the sultan / British governor had the right of nomination.[129] The British governor could depose emirs and Lugard did this ten times in 1906 alone. (Even in the Fourth Republic of Nigeria, emirs are occasionally deposed by state governors).

The emirs carried out British instructions (such as drafting recruits during the world wars) and presided over a court that spoke Islamic Maliki law but, following the opinion of the orientalist Joseph Schacht, took British law into ‘supplementary’ consideration.[130] Within an emirate, the emir was therefore the employer of the judges (Alkali / Qadi) he appointed. Each emir was officially advised by a (British) ‘resident’, but was actually controlled. The British prevented torture as a method of interrogation, the cutting off of body parts for theft and stoning to death for adultery, for example. As the Maliki school of Islamic law makes no distinction between, for example, murder and involuntary manslaughter or the (criminal) offence of vandalism and (civil) damage to property, the British introduced the principle of malice intent. Death sentences had to be authorised by the Resident[130] and children of slaves were now considered freeborn.

The emirs also collected taxes. Taxes such as the land tax kharaj and the poll tax jizyah no longer went to the emirs. Instead, each emir could retain 25 per cent of the taxes he collected for his ‘administration.’[131] The emirs thus had a financial and disciplinary motivation to be loyal to the British. Over the next few decades, Islamic law in northern Nigeria was continually restricted and by the 1940s only applied to family and inheritance law.[130]

Unification into "Crown Colony and Protectorate" 1914, Governor Lugard

In 1912, after an interlude in Hong Kong, Lugard returned as governor of the two Nigerian protectorates. He merged the two colonies into one.[111]

In the same year, Lugard, who found the inhabitants of Lagos rebellious, had a new seaport built in the south-east as a rival to Lagos and named it Port Harcourt after his superior in the Colonial Office. This seaport soon received a railway line to Enugu and shipped the coal mined there (from 1958 also crude oil) overseas.

Unification and yet separation

Lugard became the first governor of All Nigeria. The unification of Nigeria helped to give Nigeria common telegraphs, railways, customs and excise duties, uniform time,[132] a common currency[133] and a common civil service.[134] Lugard thus introduced what was needed for the infrastructure of a modern state. However, the north and south remained as two separate countries with separate administrations.[135]

In the south, English was the official language and was taught in schools, in the north Hausa.[136] Southern Nigerians thus had access to English-language literature - from scientific literature to novels; their compatriots in the north had to make do with the much less comprehensive Hausa literature, which mainly dealt with philosophical and practical questions about Islam. (This imbalance can still be found today. In 2024, for example, there are 6.8 million articles in English and 101 articles in Hausa on Wikipedia). Southern Nigerians also began to engage in literary endeavours. Since 1950, there has been an independent and dynamic Nigerian literary scene, in which the German-Jewish professor at the University of Ibadan Ulli Beier played a major role.

The protectorate in the south financed itself with £1,933,235 in tax revenue (1912). The larger but underdeveloped Northern Protectorate collected £274,989 in the same year and had to be subsidised by the British to the tune of £250,000 annually.[136] (This economic structure basically exists to this day.)

Regional differences in access to modern education soon became pronounced. Some children of the southern elite went to Britain for higher education. The imbalance between North and South was also reflected in Nigeria's political life. For example, slavery was not banned in northern Nigeria until 1936, while it was abolished in other parts of Nigeria around 1885.[137] Northern Nigeria still had between 1 million and 2.5 million slaves around 1900.[138]

The attempt to enforce this system in the south also met with varying degrees of success. In the Yoruba region of the south-west, the British were able to tie in with existing or formerly existing kingdoms and their borders. However, as there were no hierarchical or even feudal structures in the south-east through which the British could indirectly rule, they appointed "Warrant Chiefs" with powers to act as local representatives of the British administration among their people. However, the British did not realise that in some parts of Africa the concept of "chiefs" or "kings" was not known. Among the Igbo, for example, decisions were made through lengthy debates and general consensus. The new powers vested in the Warrant Chiefs and reinforced by the native court system led to an exercise of power and authority unprecedented in pre-colonial times. The Warrant Chiefs also used their power to amass wealth at the expense of their subjects. The Warrant Chiefs were corrupt, arrogant and accordingly hated.[139][140]

Governors were authorised to enact laws, otherwise English law applied. There was a Supreme Court, provincial courts and cantonal courts. Decisions of the Supreme Court could be appealed to the West African Court of Appeal. The provincial courts did not allow legal representation by lawyers and were staffed by administrative rather than judicial personnel.[130]

Racial approaches in the army

From the outset, British colonial rule utilised - and reinforced - the differences between the ethnic groups present in order to offer itself to each side as a power-preserving factor and to be able to control the oversized colony with relatively little military expenditure (4,200 British soldiers). In the south, education, economy and civilisational achievements dominated, while in the north the military, feudalism and Islamic traditions[141] were deliberately reinforced by the British. While officer positions were filled with British, enlisted men, non-commissioned officers and higher non-commissioned officer positions (sergeant majors) were exclusively filled with northern Nigerians, as these were regarded as "warrior peoples" in accordance with a popular doctrine practised in India since 1857 (e.g. Sikhs, Brahmins).[142] Nigeria thus remained divided in many respects into the northern and southern protectorates and the colony of Lagos.[143]

On Lugard, historian K. B. C. Onwubiko says: "His system of Indirect Rule, his hostility towards educated Nigerians in the South, and his system of education for the North which aimed at training only the sons of the chiefs and emirs as clerks and interpreters show him as one of Britain's arch-imperialists".[144]

First World War

In August 1914, a British-Nigerian military unit attacked Cameroon. After 18 months, the German Imperial Schutztruppe surrendered to a superior force of British, Nigerians, Belgians and French. Some German units were able to escape to the Spanish and thus neutral Rio Muni (today's Equatorial Guinea).

Time between the world wars

In the Treaty of Versailles, the German colony of Cameroon was divided up between the British and French as a League of Nations trust territory. In 1920, the western part of the former German colony of Cameroon was administratively annexed to British Nigeria as a League of Nations mandate territory under the name British Cameroons.[145]

Lugard's successor (1919–1925), Sir Hugh Clifford, was an avowed opponent of Lugard's views and saw his role not in the efficient running of an apparatus of power, but in the development of the country. He intensified educational efforts in the south and repeatedly suggested to the Colonial Office in London that the power of the absolutist emirs ruling in the north should be limited - which was rejected. This further deepened the de facto division of the country into a northern, south-western and south-eastern part. In the north, the indirect rule aimed at preserving feudal rule continued to apply. In the south, an educated elite based on the European model emerged.[124]

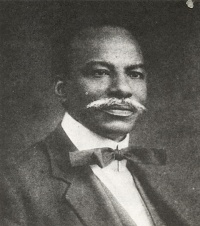

In 1922, Clifford established the Legislative Council. The four elected members were from Lagos (3) and Calabar (1). The Legislative Council enacted laws for the colony and the protectorate of Southern Nigeria. It also approved the annual budget for the entire country. The four elected members were the first Africans to be elected to a parliamentary body in British West Africa. The Clifford Constitution accordingly led to the formation of political parties in Nigeria. Herbert Macaulay, a newspaper owner and grandson of Samuel Ajayi Crowther (see above), founded the first Nigerian political party - the Nigeria National Democratic Party - in 1923. It remained the strongest party in the elections until 1939.

Nigeria's (and the Commonwealth's) contact with Great Britain was mainly maintained by mail ships of the Elder Dempster Lines.[146] Until the end of 1967, such a mail ship sailed from Liverpool to Lagos every second Friday,[147] alternating between the MS Apapa, the MS Accra and the MV Aureol. The journey took 13 days and went via Las Palmas, Bathurst (Banjul), Freetown, Monrovia and Tema with a five-day stopover in Lagos-Apapa. In addition to letters, parcels and newspapers, the mail ships also carried cargo and about 250 1st class passengers and 24 3rd class passengers, which was mainly used by nuns and Salvation Army officers (there was no 2nd class).[147] The 1st class, which consisted of colonial officials, colonial army officers, business travelers and globetrotters, had its own lounge, library, bar and smoking room. There were generous baggage allowances, which Nigerian traders were happy to fully utilize on the return journey to Lagos.[147]

The railway company paid very well due to the activities of the well-organised railway workers' union, but also due to competing employers - who were happy to poach skilled workers. High school graduates could train as train drivers or technicians ("engineers") in six-year vocational school courses run by Nigerian Railways. During this training, the "apprentices" were paid and received an annual salary of £380 - £480 (as of 1935, in today's money value about £38 - 48,000, significantly more than the average Nigerian income today).[112] For the vocational students in Lagos, the railway company had specially provided a discarded but still functional 0-6-0 steam locomotive worth £4 million (in today's money value), which they could use to learn how it worked.[112]

In the meantime, it had become clear that colonies were neither "profitable" in the sense of the marginal utility theory described above, nor were they the solution to the problem of shrinking markets. Instead, Nigeria continued to gobble up taxpayers' money despite investments totalling several billions (like most African colonies) and hardly benefited the economy of the mother country. The new governor Graeme Thomson therefore introduced harsh austerity measures in 1925, including massive redundancies and the introduction of direct taxation.

The planned tax on women market traders, Graeme Thomson's undiplomatic manner and the unpopular Warrant Chief system (see above) led to the "Women's War" of 1929 among the Igbo. The women farmers destroyed ten native courts by December 1929, when the troops restored order in the region. In addition, the houses of chiefs and employees of the native courts were attacked, European factories looted, prisons attacked, and prisoners released. The women demanded the removal of the Warrant Chiefs and their replacement by native clan chiefs appointed by the people and not by the British. 55 women were killed by the colonial troops. Nevertheless, the Women's War of 1929 led to fundamental reforms in the British colonial administration. The British abolished the system of "Warrant Chiefs" and reviewed the nature of colonial rule over the natives of Nigeria. Several colonial administrators condemned the prevailing administrative system and agreed to the call for urgent reforms based on the indigenous system. In place of the old Warrant Chief system, tribunals were introduced that took into account the indigenous system of government that had prevailed before colonial rule.[148][149]

In 1933, the Lagos Youth Movement - later the Nigerian Youth Movement - was founded[148] and took a more strident stance in favour of independence than the NNDP. In 1938, the NYM called for Nigeria to be granted British Dominion status, putting it on a par with Australia or Canada.[124] In 1937, it was joined by Nnamdi Azikiwe, who had been exiled from Ghana/Gold Coast for seditious activities and who became publisher and editor-in-chief of the West African Pilot and father of Nigerian popular journalism. In 1938, the NYM protested against the cocoa cartel, which kept the purchase prices from farmers artificially low.[119] In 1939, the NYM became the strongest party in the elections in Lagos and Calabar (no elections were held elsewhere).

In 1934, the Warrant Chiefs were abolished.[150] In 1935, the railway network reached its maximum expansion after the last investment projects were completed. It comprised 2,851 km of track with a gauge of 106.7 cm ("Cape gauge") and 214 km with a gauge of 76.2 cm. This made the Nigerian railway network the longest and most complex in West and Central Africa. In 1916, a 550 m long railway bridge over the Niger River and in 1934 a bridge over the Benue River connected the regional railway networks.[112] 179 mainline and 54 shunting locomotives were in use in 1934. Two maintenance and repair workshops in Lagos and Enugu employed about 2,000 locals.[112] Rail transport was efficiently synchronised with maritime traffic. Travellers from mail steamers could board the "Boat Express" waiting right next to it at the port of Apapa in Lagos and reach Kano in the far north of Nigeria within 43 hours in sleeping and dining cars.[112]

In 1931, the influential Nigerian Union of Teachers was founded under its president O. R. Kuti (the father of Fela Kuti).[150] Nigeria's first industrial union, the railway workers' union, was also founded in 1931 by lathe operator Michael Imoudu.[151] In 1939, trade unions were permitted by decree by the colonial administration, but Imoudu was arrested in 1943. The railway workers' union was considered the most militant workers' union in Nigeria. Imoudu remained under house arrest until 1945.[152]

Governor Cameron standardised the administration of the Northern and Southern Provinces in the 1930s by introducing a native appellate court system, High Courts and Magistrate Courts.

Bernard Bourdillon became governor of Nigeria in 1935 and remained so for eight years.[153] He maintained close contact with local politicians, especially the NYM.[154] Bourdillon, who always opposed any form of racism,[154] was presumably the only governor in Nigeria who saw himself as a representative of the country's interests - especially against prevailing views in the mother country. In the Colonial Office, he succeeded in 1938 in ensuring that the purchasing cartel for West African products such as cocoa, palm oil and peanuts was no longer supported by the British government.[154] (The cartel included companies such as Unilever, Nestlé, Cadbury, Fry's, Swiss African Trading Co, CFAO/Verminck, Union Trading Co/Basler Mission, G.B. Ollivant, Société commerciale de l'Ouest africain (SCOA), PZ Cussons/Zochonis, and others.[155]) He involved the backward north more closely in political processes by creating a "Central Council".[156]

Second World War

Sinking of both mail ships to Nigeria

On 26 July 1940, one of the two mail ships connecting Nigeria with the colonial power, the MS Accra, was sunk off Ireland by the U-34 submarine. 24 people died.

On 15 November 1940, the sister ship on the same route, the MS Apapa, was sunk by a German FW 200 Condor on its way home off Ireland. 26 people lost their lives.[157] An identical ship was given the same name and took over the same route service (see picture above).[158]

Operation Postmaster

In 1942, Nigeria played a role in "Operation Postmaster". In an adventurous manner, British special agents from Lagos captured Italian and German supply ships for submarines in the South Atlantic on the nearby but Spanish and therefore neutral island of Bioko and brought them to the home port of Lagos.[159] The incident - in which no shots were fired - almost led to Franco's Spain entering the war alongside the Third Reich and fascist Italy.

Rationing, price control, agricultural damage, education offensive

As early as 1939, the Nigeria Supply Board was set up to promote the production of rubber and palm oil, which were considered important for the war effort, at the expense of food production. The import of agricultural products was restricted.

From 1942, farmers were only allowed to sell rice, maize, beans etc. to government agencies and at a very low price under the "Pullen Scheme" so that the British Isles, which were cut off from the continent, could be supplied with food at low cost. However, this price control motivated farmers to either not sell their products at all or to sell them on the black market. Others may have resorted to growing unregulated, i.e. inedible, produce. Nigeria's agriculture, which had already suffered from the European purchasing cartels (especially Unilever) and the Great Depression, was once again hampered in its development.[160] In December 1942, consumer goods were rationed. (Rationing would last until 1948.)[161] The transport of rice from Abeokuta to nearby Lagos was criminalised.

As a "positive" effect of the Second World War, the colonial administration trained war-critical skilled labour such as technicians, electricians, nurses, carpenters and clerks on a large scale during this period. New harbours and - for the first time - airports were built.[162]

From October 1941 to January 1945, the 44th British General Hospital was stationed in Abeokuta, not far from Lagos. Soldiers, airmen and sailors could recover from their injuries here. There was also the 46th British General Hospital in Kaduna in 1942 and 1943.[163]

Nigeria regiments, advance in Ethiopia

Throughout the war, 45,000 Nigerian soldiers served in the British forces in Africa and South-East Asia. Nigerian regiments formed the majority of the British Army's 81st and 82nd West African Divisions.[164] These divisions fought in Palestine, Morocco, Sicily and Burma. Nigerian soldiers also fought in India.

Three battalions of the Nigeria Regiment fought in the Ethiopian campaign against fascist Italy. On 26 March 1941, two motorised companies of the Nigeria Regiment advanced 930 km from Kenya to Daghabur within 10 days in Mussolini-controlled Ethiopia. On 26 March, the Nigeria Regiment captured Harar near Djibouti after an advance of 1,600 km in 32 days. At the time, this was the fastest military advance in world history.[12] The advance also divided the fascist sphere of control in East Africa. In their hasty retreat, the Italian forces also left behind important ammunition and food depots. Addis Ababa was conquered by the Allies on 6 April.[165] The Ethiopian campaign became the Allies' first major success against the Axis powers, not least due to the "Blitzkrieg" of the Nigeria regiment.[12] With East Africa (1.9 million km2), Italy lost an area in a few days that was larger than today's Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and the Baltic states combined (1.3 million km2).

Ideas from India on independence

Fighting for the Allies were 600,000 volunteers from Africa, who had been promised equal brotherhood in arms with their Caucasian fellow soldiers. Nevertheless, they received less pay than their European or Asian counterparts.[166] Corporal punishment (flogging) was also still a disciplinary punishment exclusively for black soldiers. In northern Nigeria, it is not necessarily possible to speak of "voluntary" recruits, as the local tribal chiefs were prescribed contingents of "volunteers" as part of the Indirect Rule. The absolutist rulers did not necessarily take into account the voluntary nature of the troops when providing them for service at the front. During the war, none of the commanding officers of the Nigerian Corps came from Nigeria. (The first Nigerian officers received their licences at the end of the war).

The Nigerian soldiers can hardly have been unaware of the contradiction between their reality and the propagated British interpretation of wanting to protect Africa from German and Italian colonisation.[166] In addition, the Nigerian troops had been fighting alongside their Indian comrades for several years and there was already a strong and media-effective independence movement against British colonial rule in their homeland under Mahatma Gandhi. (India became independent just 22 months after the Second World War.) The exchange of ideas with the Indians striving for independence almost certainly contributed to the fact that Nigerian soldiers returned home from Burma in January 1946[167] with completely new ideas about an independent Nigeria, but with less patience.

In his victory speech, the commander of the troops in Burma, Sir William Slim, did not mention the Nigerian "brothers in arms" at all.[168]

Post-war period, the road to independence

During the Second World War, the number of Nigerian trade union members had increased sixfold to 30,000.[124] A general strike by railway workers for higher wages and for the release of imprisoned trade unionists such as Michael Imoudu (see above) made it clear in 1945 that the previous colonial administration had to be replaced by a new, national form of government.[169][170]

The new governor of Nigeria, Richards, like Graeme Thomson and Bourdillon an ‘Oxford man’, introduced a constitution in 1946 that turned the country into a federation consisting of three states with uninspiring names such as ‘Northern/Western/Eastern Region’ and their own parliaments, governments and constitutions (the East had one house of parliament, the West and North a bicameral system). These would establish a central government for customs matters, common foreign policy and defence.

In retrospect, the Richards Constitution must be viewed critically and it was also viewed critically by Nigerians at the time. Money was collected in a campaign to enable the three most respected compatriots (newspaper publisher Macaulay, trade union leader Imoudu and journalist Azikiwe) to travel to London to present their views (ultimately unsuccessfully) to the Attlee government there.[171] The British government in faraway London was apparently of the opinion that it knew better what was good for Nigerians than Nigerians themselves. After all, the constitution was slightly modified in 1951 and 1954; the last version, finally adopted by and named after the colonial minister Oliver Lyttelton, the son of the 4th Baron Lyttleton and later himself 1st Viscount Chandos, was the constitution with which Nigeria would become independent in 1960. Although there had been two conferences on the subject (one in London, the other in Lagos), these only had an advisory function: the constitution of independent Nigeria of 1960 was not the result of a constituent assembly of Nigerians, but a creation of British colonial ministers and governors, among whom (both) English aristocrats and Oxford graduates were still predominant at the time - representatives of the British upper class.

In this federation of just three federal states, the political process naturally became more of a conflict than a co-operation. Accordingly, the dominant political parties were organised along ethnic lines:

- The Northern Peoples Congress (NPC) represented the eponymous northern Nigerians, especially the Hausa, and was led by one of the highest nobles of the north, Ahmadu Bello,

- The National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) represented the Igbo in the south-east after the death of Herbert Macaulay under the leadership of journalist Nnamdi Azikiwe, and

- The Action Group (AG) represented the Yoruba in the south-west and had Obafemi Awolowo as party leader.