History of Malappuram district

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Kerala |

|---|

Malappuram is one of the 14 districts in the South Indian state of Kerala. The district has a unique and eventful history starting from pre-historic times. During the early medieval period, the district was the home to two of the four major kingdoms that ruled Kerala. Perumpadappu was the original hometown of the Kingdom of Cochin, which is also known as Perumbadappu Swaroopam, and Nediyiruppu was the original hometown of the Zamorin of Calicut, which is also known as Nediyiruppu Swaroopam. Besides, the original headquarters of the Palakkad Rajas were also at Athavanad in the district.[1]

Ancient period

The remains of some pre-historic symbols including Dolmens, Menhirs, and Rock-cut caves have been found from various parts of the district. Rock-cut caves have been found from the places like Puliyakkode, Thrikkulam, Oorakam, Melmuri, Ponmala, Vallikunnu, and Vengara.[2] The ancient maritime port of Tyndis, which was a centre of trade with Ancient Rome, is roughly identified with Ponnani, Tanur, and Vallikkunnu-Kadalundi-Chaliyam-Beypore region. Tyndis was a major center of trade, next only to Muziris, between the Cheras and the Roman Empire.[3] Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) states that the port of Tyndis was located at the northwestern border of Keprobotos (Chera dynasty).[4] The North Malabar region, which lies north of the port at Tyndis, was ruled by the kingdom of Ezhimala during Sangam period.[5] According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a region known as Limyrike began at Naura and Tyndis. However the Ptolemy mentions only Tyndis as the Limyrike's starting point. The region probably ended at Kanyakumari; it thus roughly corresponds to the present-day Malabar Coast. The value of Rome's annual trade with the region was estimated at around 50,000,000 sesterces.[6] Pliny the Elder mentioned that Limyrike was prone by pirates.[7] The Cosmas Indicopleustes mentioned that the Limyrike was a source of peppers.[8][9] The River Bharathappuzha (River Ponnani) had importance since Sangam period (1st-4th century CE), due to the presence of Palakkad Gap which connected the Malabar coast with Coromandel coast through inland.[10]

Early medieval period

The Kurumathur inscription found near Areekode dates back to 871 CE.[11] Three Old Malayalam inscriptions those date back to 932 CE, those were found from Triprangode (near Tirunavaya), Kottakkal, and Chaliyar, mention the name of Goda Ravi of Chera dynasty.[12] The Triprangode inscription states about the agreement of Thavanur.[12] Several inscriptions written in Old Malayalam those date back to 10th century CE, have found from Sukapuram near Edappal, which was one of the 64 old Nambudiri villages of Kerala. Descriptions about the rulers of Eranad region and Valluvanad region can be seen in Jewish copper plates of Bhaskara Ravi Varman and Viraraghava copper plates of Veera Raghava Chakravarthy.[2] A number of city-states were there in the region, including Valluvanad, Vettathunadu (Tanur), Parappanad and Nediyiruppu (Eranad) (ruled by the Zamorins).[13][14]

Rise of the Zamorin of Calicut

During and around the fall of Perumal Empire, Calicut and its environs were ruled over by Porlathiri. Eranad was ruled by a Samanthan Nair clan known as Eradis, similar to the Vellodis of neighbouring Valluvanad and Nedungadis of Nedunganad. The rulers of Eranad were known by the title Eralppad/Eradi. The Eradis (A title used to denote the rulers of Eranad) of Nediyiruppu marched with their army to Panniyankara and often surrounded the headquarters of Porlathiri. The ultimate aim was to find access to the sea and thus to participate directly in the maritime trade. This war lasted for almost half a century. The battle ended in the victory of the Eradis. Porlathiri fled to Kolathunadu in search of political asylum.

With the conquest of Polanad, the Eradis who ruled Eranad shifted their headquarters from Nediyiruppu to Calicut, and later began to known as the Zamorin of Calicut. In the early stage of his territorial development, Zamorin expanded his territories to Parappanad and Vettathunad by defeating their rulers.[15][16]

The power balance in Kerala changed as Eralnadu rulers developed the port at Kozhikode. The Samoothiri became one of the most powerful chiefs in Kerala.[17] In some of his military campaigns – such as that into Valluvanadu – the ruler received unambiguous assistance from the Muslim Middle Eastern sailors.[18] It seems that the Muslim judge of Kozhikode offered all help in "money and material" to the Samoothiri to strike at Thirunavaya.[17] Smaller chiefdoms south of Kozhikode – Beypore, Chaliyam, Parappanadu and Tanur (Vettam) – soon had to submit and became their feudatories one by one.

The ruler of Kozhikode next turned his attention to the valley of Bharathappuzha. Large parts of the valley were then ruled by Valluvakkonathiri, the hereditary chief of Valluvanadu. The principal objective of Kozhikode was the capture the sacred settlement of Thirunavaya. The rivalry that existed between the Nambudiris in the Nambudiri villages of Panniyoor and Chowwara (Sukapuram) was also of great political importance in medieval Kerala.[15] Panniyoor is situated opposite to Kuttippuram town while Sukapuram lies in Edappal. Soon the Samoothiris found themselves intervened in the so-called kurmatsaram between Nambudiris of Panniyurkur and Chovvarakur. In the most recent event, the Nambudiris from Thirumanasseri Nadu had assaulted and burned the nearby rival village. The rulers of Valluvanadu and Perumpadappu came to help the Chovvaram and raided Panniyur simultaneously. Thirumanasseri Nadu was overran by its neighbours on south and east. The Thirumanasseri Nambudiri appealed to the ruler of Kozhikode for help, and promised to cede the port of Ponnani to Kozhikode as the price for his protection. Kozhikode, looking for such an opportunity, gladly accepted the offer.[17]

Assisted by the warriors of their subordinate chiefs (Chaliyam, Beypore, Tanur and Kodungallur) and the Muslim naval fleet under the Koya of Kozhikode, the Samoothiri's fighters advanced by both land and sea.[17] The main force under the command of Samoothiri himself attacked, encamping at Triprangode, an allied force of Valluvanadu and Perumpadappu from the north. Meanwhile, another force under the Eralppadu commanded a fleet across the sea and landed at Ponnani and later moved to Thirumanasseri, with an intention to descend on Thirunavaya from the south with help of the warriors of the Thirumanasseri Brahmins. Eralppadu also prevented the warriors of Perumpadappu from joining Valluvanadu forces. The Muslim merchants and commanders at Ponnani supported the Kozhikode force with food, transport, and provisions. The warriors of the Eralppadu moved north and crossed the Bharathappuzha and took up position on the northern side of the river.[17] The Koya marched at the head of a large column and stormed Tirunavaya. In spite of the fact that the warriors of Valluvanadu did not get the timely help of Perumpadappu, they fought vigorously and the battle dragged on. In the meantime, the Kozhikode minister Mangattachan was also successful in turning Kadannamanna Elavakayil Vellodi (junior branch of Kadannamanna) to their side. Finally, two Valluvanadu princes were killed in the battles, the Nairs abandoned the settlement and Kozhikode infested Tirunavaya.[17]

The capture of Thirunavaya was not the end of Kozhikode's expansion into Valluvanadu. The Samoothiri continued surges over on Valluvanadu. Malappuram, Nilambur, Vallappanattukara and Manjeri were easily occupied. He encountered stiff resistance in some places and the fights went on in a protracted and sporadic fashion for a long time. Further assaults in the east against Valluvanadu were neither prolonged nor difficult for Kozhikode.[17]

The battles along the western borders of Valluvanadu were bitter, for they were marked by treachery and crime. Panthalur and Ten Kalams came under Kozhikode only after a protracted struggle. The assassination of a minister of Kozhikode by the chief minister of Valluvanadu while visiting Kottakkal in Valluvanadu sparked the battle, which dragged on for almost a decade. At last, the Valluvanadu minister was captured by Samoothiri's warriors and executed at Padapparambu, and his province (Ten Kalams, including Kottakkal and Panthalur) was occupied by the Samoothiri. The Kizhakke Kovilakam Munalappadu, who took a leading part in this campaign, received half of the newly captured province from Samoothiri as a gift. The loss of this fiercely loyal chief minister was the greatest blow to Valluvanadu after the loss of Tirunavaya and Ponnani.[17]

The port of Ponnani was a prominent centre of Islamic learning and Tirunavaya was a centre of Vedic learning in medieval Kerala. The ports of Ponnani, Tanur and Parappanangadi had some of the oldest Muslim settlements in Kerala originated as a result of the trade relationship.

Late medieval period

Thrikkavil Kovilakam in Ponnani served as a second home for Zamorin, and his navy headquarters.[19] Archaeological relics found in Malappuram include the remnants of palaces of the eastern branch of the Zamorin reign. Malappuram was the military headquarters of the Zamorin in the Eranad region. The Zamorins held sway over Malappuram and their chieftain Para Nambi, ruled the area in the early days with headquarters at Downhill (Kottappadi), Malappuram.[20] Zamorin earned a greater part of his revenue by taxing the spice trade through his ports. Smaller ports in kingdom included Parappanangadi, Tanur, and Ponnani.[17][21] The headquarters of the Azhvanchery Thamprakkal, who were considered as the supreme religious head of Kerala Brahmins, was at Athavanad. Besides, the original headquarters of the Palakkad Rajas were also at Athavanad.[1]

The works like Kozhikode Granthavari, Mamakam Kilippattu written by Kadanchery Namboodiri in 17th-century CE, Kandaru Menon Patappattu (1683), and Ramchcha Panicker Pattu contains pieces of information about the Mamankam festival held at the bank of Bharathappuzha in Tirunavaya.[22] The modern Malayalam alphabet (accepted by Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan), and the Arabi-Malayalam script (also known as Ponnani script) were developed in the district during the medieval period. The Sanskrit works like Kokila Sandeśa (15th-century CE) written by Uddanda Śāstrī, Bhramara Sandesham (17th century CE) by Vasudevan, and Chathaka Sandesha (18th-century CE) have descriptions about Tirunavaya and Triprangode.[15] Many medieval Malayalam works also help to trace the history of district.

Portuguese era

The ruler of the Kingdom of Tanur, who was a vassal to the Zamorin of Calicut, sided with the Portuguese, against his overlord at Kozhikode.[15] As a result, the Kingdom of Tanur (Vettathunadu) became one of the earliest Portuguese Colonies in India. The ruler of Tanur also sided with Cochin.[15] Many of the members of the royal family of Cochin in 16th and 17th centuries were selected from Vettom.[15] However, the Tanur forces under the king fought for the Zamorin of Calicut in the Battle of Cochin (1504).[23] However, the allegiance of the Mappila merchants in Tanur region still stayed under the Zamorin of Calicut.[24] Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan, who is considered as the father of modern Malayalam literature, was born at Tirur (Vettathunadu) during Portuguese period.[15] The medieval Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics that flourished between the 14th and 16th centuries, was also primarily based in Vettathunadu (Tirur region)[25][26]

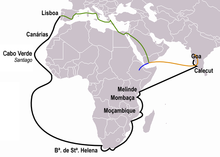

In the 16th century, the district witnessed several battles between Kozhikode naval chiefs, known as the Kunhali Marakkars, and the Portuguese colonizers. Towards the end of the year 1507, the Portuguese Viceroy Francisco de Almeida was informed that a column of 13 Muslim ships had taken cargo - mainly spices - from Ponnani and was about to leave for the Red Sea. The Viceroy immediately decided to corner the fleet. The decision was perhaps made with a view to retrieve the Portuguese prestige lost on account of some incidents at Angediva and Dabul. Almeida himself commandeered the fleet of 12 vessels consisting of four naus, six caravels, and two gales. The fleet had about 6,000 European soldiers, led by a collection of noblemen such as Pero Barreti, Diogo Pires, Lourenco de Almeida, and Nuno da Cunha, son of Tristao da Cunha and a handful of Cochin soldiers.[27]

The defenses of the Ponnani Port were repaired and strengthened by the Zamorin after this event.[19][28] The Zamorin appointed Kunjali Marakkar I, his loyal naval chief, in the port of Ponnani, to resist the Portuguese occupation. The Kunjali Marakkars are credited with organizing the first naval defense of the Indian coast.[29][30] It seems that Kunjali Marakkar I, assisted by Kutti Ali and Pacchi Marakkar, subsequently constructed a naval base at Ponnani. Kutti Ali sent harassing raids from Ponnani to Cochin and reinforcement fleets to Kozhikode.[28] In 1523 when the Viceroy Menezes sailed with all the available ships to Hormuz, an Arab merchant, one Kutti Ali of Tanur, had the effrontery to bring a fleet of two hundred vessels to Calicut, to load eight ships with pepper, and to despatch them with a convoy of forty vessels to the Red Sea before the very eyes of the Portuguese.[31]

The Zamorin later faced a protest in 1540 by Kutti Pocker, who is popularly known as Kunjali Marakkar II (a title given to the naval chief of the Zamorin) when the Zamorin signed a treaty with the Portuguese power in Ponnani.[32] Tanur town was one of the earliest Portuguese colonies in the Indian subcontinent. In 1552, the Zamorin received assistance in heavy guns landed at Ponnani, brought by certain Yoosuf, a Turk, who had sailed against the monsoon winds. In 1566 and again in 1568, Kutti Pocker and his men captured two Portuguese ships. Around a thousand soldiers from one of these ships were killed either by the sword or drowning. Kutti Pocker was later in killed off the coast of Mangalore while returning from a successful raid on the Portuguese fort there.[31]

A Portuguese fleet of 40 vessels under the command of Diogo de Meneses is known to have pillaged Ponnani, sometime before 1570 AD.[28][33] The strategic Chaliyam - also known as Challe- which was then a part of the Kingdom of Tanur, was a Portuguese garrison between 1531–1571.[34] Chāliyam was a strategic site, for it was only 10 km south of Calicut and was situated in Chaliyar River that falls into the sea about three leagues from Calicut, which was navigable by boats all the way to the foot of the Western Ghats mountains throogh Nilambur valley.[35] In 1532 with the help of the ruler of Tanur, a chapel was built at Chaliyam, together with a house for the commander, barracks for the soldiers, and store-houses for trade. Diego de Pereira, who had negotiated the treaty with the Zamorin, was left in command of this new fortress, with a garrison of 250 men; and Manuel de Sousa had orders to secure its safety by sea, with a squadron of twenty-two vessels.[35] The Zamorin soon repented of having allowed this fort to be built in his dominions, and used ineffectual endeavours to induce the ruler of Parappanangadi, Caramanlii (King of Beypore?) (Some records say that the ruler of Tanur was also with them[35]) to break with the Portuguese, even going to war against them.[24] In 1571, the Zamorin sent against the Fort Chaliyam certain of his ministers in command over the Moors (a term used by William Logan to indicate Mappilas and Arab Merchants) of Ponnani, Tanur, and Parappanangadi, who was assisted by bodies of people from Chaliyam. The army led by troops of Zamorin won to seize the Portuguese fort at Chaliyam[19] In 1573, Parappanangadi town was burnt by the Portuguese. In 1578, peace negotiations between Zamorin and the Portuguese were strengthened. However, the Zamorin refused to agree to construct a Portuguese fort at Ponnani.[31] It is also known that Gil Eanes Mascarenhas opened fire from his ships to the port and killed a large number of natives in 1582. Mascarenhas was later captured and executed by the forces of Kunjali Marakkar.[36]

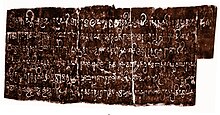

The Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen written by Zainuddin Makhdoom II (born around 1532) in Ponnani during 16th-century CE is the first-ever known book fully based on the history of Kerala, written by a Keralite. It is written in Arabic and contains pieces of information about the resistance put up by the navy of Kunjali Marakkar alongside the Zamorin of Calicut from 1498 to 1583 against Portuguese attempts to colonise Malabar coast.[37] It was first printed and published in Lisbon. A copy of this edition has been preserved in the library of Al-Azhar University, Cairo.[38][39][40]

Colonial period

When William Keeling, a sea captain of English East India Company arrived at the Kingdom of Calicut in 1615, he was allowed to start warehouses in the port of Ponnani, through a treaty signed with the then Zamorin of Calicut.[41] By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Dutch had attained monopoly over trade in many ports in Kerala. However, some factories in Ponnani came under the trade monopoly of English.[42] During 18th century, the de facto Mysore kingdom rulers Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan marched into Zamorin's kingdom. With headquarters at Manjeri, Tipu's army was spread in many areas.[41] Tipu had a fort at Paloor near Perinthalmanna on his way from Palakkad to the Zamorin's kingdom, where now a waterfall only remains.

The Battle of Tirurangadi was a series of engagements that took place between the British army and Tipu Sultan between 7 and 12 December 1790 at Tirurangadi, during the Third Anglo-Mysore War.[43] In 1792, Tipu Sultan was defeated by English East India Company through Third Anglo-Mysore War, and the Treaty of Seringapatam was agreed. As per this treaty, most of the Malabar region, including present-day Malappuram district, was integrated into the English East India Company. In 1793, the district became a part of the newly formed Malabar.

On 20 May 1800, the East India Company separated Malabar from Bombay Presidency and annexed it with the Madras Presidency. The British had established a Barracks called Haig Barracks in the city of Malappuram, which has now been turned into Malappuram Collectorate.[44] Malappuram acted as the military headquarters of British Malabar, as it was the centre of Malabar Special Police. Malabar Special Police is also the oldest armed police battalion in the state. The district was the venue for many of the Mappila revolts (uprisings against the British East India Company in Kerala) between 1792 and 1921. It is estimated that there were about 830 riots, large and small, during this period. Muttichira revolt, Mannur revolt, Cherur revolt, Manjeri revolt, Wandoor revolt, Kolathur revolt, Ponnani revolt, and Thrikkalur revolt are some important revolts during this period. During 1841–1921 there were more than 86 revolutions against the British officials alone.[45] East India Company made an arrangement to collect revenue through Zamorin. However, a revolt under the leadership of Manjeri Athan Gurukkal took place against this in 1849.[42] The district was administered as parts of Eranad, Valluvanad and Ponnani subdistricts in the South Malabar region during the British rule. The oldest teak plantation of the world at Conolly's plot is just 2 km (1.2 mi) from Nilambur town. It was named in memory of Henry Valentine Conolly, the then district collector of Malabar.[46] The first railway line in the state started its function from Tirur to Beypore on 12 March 1861, with the oldest Railway Station at Tirur.[47][48] The Koyi Thampurans of Travancore belongs to Parappanad Royal Family. It was from this family that the consorts of the Rani's Travancore family were usually selected.[49]

Malabar Rebellion

The Malabar district political conference of Indian National Congress held at Manjeri on 28 April 1920 strengthened Indian independence movement and national movement in British Malabar.[50] That conference declared that the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms were not able to satisfy the needs of British India. It also argued for a land reform to seek solutions for the problems caused by the tenancy that existed in Malabar. However, the decision widened the drift between extremists and moderates within the Congress. The conference resulted in the dissatisfaction of landlords with the Indian National Congress. It caused the leadership of the Malabar district Congress Committee to come under the control of the extremists who stood for labourers and the middle class.[15]

Malappuram has been part of Khilafat Movement just after the Manjeri conference. The Khilafat non-cooperation demonstration conducted at Kalpakanchery in Ponnani Taluk (now a part of Tirur Taluk) on 22 March 1921 under the leadership of K. P. Kesava Menon was attended by about 20,000 people. The first all Kerala provincial conference of Indian National Congress held at Ottapalam in April 1921 also influenced the rebellion. Malabar Rebellion of 1921 was the last and important among the Mappila rebellions.

The cities/towns of Malappuram, Manjeri, Kondotty, Perinthalmanna, and Tirurangadi were the main strongholds of the rebels. The Battle of Pookkottur occurred as a part of the rebellion. After the army, police, and British authorities fled, the declaration of independence took place over 200 villages in Eranad, Valluvanad, Ponnani, and Kozhikode taluks.[51] The new country was given the name Malayala Rajyam (The land of Malayalam).[52] On 25 August 1921, Variyankunnath Kunjahammad Haji inaugurated the Military Training Center at Angadipuram, which was started by the revolutionary government. The feudal customs of Kumpil Kanji and Kanabhumi were abolished and the tenants were made landowners. A tax exemption was given for one year and a tax was imposed on the movement of goods from Wayanad to Tamil Nadu.[53] Similar to the British, the structure of administration was built upon Collector, Governor, Viceroy, and King.[54] The parallel government established courts, tax centers, food storage centers, the military, and the legal police. Passport system was introduced for those in the new country.[55][56] Although the nation's lifespan is less than six months, some British officials have suggested that the region was ruled by a parallel government for more than a year.[57] [58]

The rebels won to establish self-rule in the region for about six months. However less than six months after the declaration of autonomy, the East India Company reclaimed the territory and annexed it to the British Raj. The war was directly controlled by British Army Commander-in-Chief Chief Rawlson, General Barnett Stuart, Intelligence Chief Maurice Williams, and Police General Armitage. Many of the important British military regiments including Dorset, Karen, Yenier, Linston, Rajputana, Gorkha, Garwale, and Chin Kutchin reached Malabar for the reannexation of the South Malabar.[59] The Wagon tragedy (1921) is still a saddening memory of the Malabar rebellion, where 64 prisoners died on 20 November 1921.[60] The prisoners had been taken into custody following the Mappila Rebellion in various parts of the district. Their deaths through apparent negligence generated sympathy for Indian independence movement.

Post-colonial period

Malabar remained as a part of the state of Madras for a few years after the declaration of Indian independence.

Malappuram was one of the five revenue divisions in the Malabar district with the Taluks of Eranad (headquartered at Manjeri) and Valluvanad (headquartered at Perinthalmanna) under its jurisdiction, while the other four being Thalassery, Kozhikode, Palakkad and Fort Cochin.[61]

Later in 1956, Malabar merged with the erstwhile state of Travancore-Cochin to form Kerala following the linguistic reorganisation of states. The newly merged Malabar was divided into Kannur, Kozhikode, and Palakkad districts of Kerala in 1957. The Eranad Taluk of erstwhile Malappuram revenue division was added to the new Kozhikode district and Valluvanad Taluk was added to Palakkad. Large-scale changes in the territorial jurisdiction of the region took place between 1957 and 1969. On 1 January 1957, the Tirur subdistrict was formed by adjoining major portions of the Eranad and Ponnani subdistricts. Another portion of the Ponnani subdistrict was carved out to form Chavakkad subdistrict (in Thrissur district), and the remainder is the present-day Ponnani. Perinthalmanna was formed by carving out some portions from the erstwhile Valluvanad subdistrict. Of these, Eranad and Tirur subdistricts remained in Kozhikode district, while Perinthalmanna and Ponnani subdistricts continued in Palakkad.

Present day district

In 1969, following intense demand from Indian Union Muslim League and various organizations the district of Malappuram was formed by the Saptakakshi Munnani government of Kerala.[62] The new district was formed with four subdistricts (Eranad, Perinthalmanna, Tirur, and Ponnani), four towns, fourteen developmental blocks, and 95 Gram panchayats at the time.[63] Later, Tirur Taluk was bifurcated to form Tirurangadi Taluk, and Eranad Taluk was trifurcated to form two more Taluks namely Nilambur and Kondotty.

In the early years of Communist rule in Kerala, Malappuram experienced land reform under the Land Reform Ordinance. In the 1970s, the oil reserves in the Persian Gulf countries were opened to commercial extraction and thousands of unskilled workers migrated to the gulf. They sent money home, supporting the rural economy, and by the late 20th century, the region attained First World health standards and near-universal literacy.[64]

See also

- Administration of Malappuram

- Education in Malappuram

- List of desoms in Malappuram (1981)

- List of Gram Panchayats in Malappuram

- List of people from Malappuram

- List of villages in Malappuram

- Transportation in Malappuram

- Malappuram metropolitan area

- Malappuram district

- South Malabar

References

- ^ a b Shreedhara Menon, A (2007). 'Kerala Charitram. Kottayam: DC Books. p. 200. ISBN 9788126415885. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ a b "History of Malappuram" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India, Yogesh Sharma, Primus Books 2010

- ^ Gurukkal, R., & Whittaker, D. (2001). In search of Muziris. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 14, 334-350.

- ^ A. Shreedhara Menon, A Survey of Kerala History

- ^ According to Pliny the Elder, goods from India were sold in the Empire at 100 times their original purchase price. See [1]

- ^ Bostock, John (1855). "26 (Voyages to India)". Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). Christian Topography. 11. United Kingdom: The Tertullian Project. pp. 358–373.

- ^ Das, Santosh Kumar (2006). The Economic History of Ancient India. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 301.

- ^ Subramanian, T. S (28 January 2007). "Roman connection in Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Veluthat, Kesavan (1 June 2018). "History and historiography in constituting a region: The case of Kerala". Studies in People's History. 5 (1): 13–31. [2] Archived 13 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumals of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 438-42.

- ^ Nair, K. K. (2013). By Sweat and Sword: Trade, Diplomacy and War in Kerala Through the Ages. KK Nair. ISBN 978-81-7304-973-6.

- ^ Ramachandran, C. M. Problems of Higher Education in India: A Case Study. Mittal Publications.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sreedhara Menon, A. (2007). A Survey of Kerala History (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 9788126415786. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Dr. Hari Desai. "The Zamorins of Calicut and Vasco Da Gama". asian-voice.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i K. V. Krishna Iyer, Zamorins of Calicut: From the earliest times to AD 1806. Calicut: Norman Printing Bureau, 1938.

- ^ V. V., Haridas. "King court and culture in medieval Kerala – The Zamorins of Calicut (AD 1200 to AD 1767)". [3] Archived 13 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine Unpublished PhD Thesis. Mangalore University

- ^ a b c K. V. Krishna Iyer Zamorins of Calicut: From the Earliest Times to AD 1806. Calicut: Norman Printing Bureau, 1938

- ^ Logan, William. MALABAR MANUAL: With Commentary by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS (Volume 2 ed.). VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS, Aaradhana, DEVERKOVIL 673508. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Kunhali. V. "Calicut in History" Publication Division, University of Calicut (Kerala), 2004

- ^ K.P. Padmanabha Menon, History of Kerala, Vol. II, Ernakulam, 1929, Vol. II, (1929)

- ^ Logan, William (2010). Malabar Manual (Volume-I). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 631–666. ISBN 9788120604476.

- ^ a b S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942). Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language. University of Madras.

- ^ Roy, Ranjan (1990). "Discovery of the Series Formula for π by Leibniz, Gregory, and Nilakantha". Mathematics Magazine. 63 (5): 291–306. doi:10.2307/2690896. JSTOR 2690896.

- ^ Pingree, David (1992), "Hellenophilia versus the History of Science", Isis, 83 (4): 554–563, Bibcode:1992Isis...83..554P, doi:10.1086/356288, JSTOR 234257, S2CID 68570164,

One example I can give you relates to the Indian Mādhava's demonstration, in about 1400 A.D., of the infinite power series of trigonometrical functions using geometrical and algebraic arguments. When this was first described in English by Charles Whish, in the 1830s, it was heralded as the Indians' discovery of the calculus. This claim and Mādhava's achievements were ignored by Western historians, presumably at first because they could not admit that an Indian discovered the calculus, but later because no one read anymore the Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society, in which Whish's article was published. The matter resurfaced in the 1950s, and now we have the Sanskrit texts properly edited, and we understand the clever way that Mādhava derived the series without the calculus, but many historians still find it impossible to conceive of the problem and its solution in terms of anything other than the calculus and proclaim that the calculus is what Mādhava found. In this case, the elegance and brilliance of Mādhava's mathematics are being distorted as they are buried under the current mathematical solution to a problem to which he discovered an alternate and powerful solution.

- ^ K. S. Mathew, Shipbuilding, Navigation and the Portuguese in Pre-modern India Routledge, 2017

- ^ a b c K. K. N. Kurup India's Naval Traditions Northern Book Centre, 1997

- ^ "Maritime Heritage - Join Indian Navy | Government of India". www.joinindiannavy.gov.in. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Singh, Arun Kumar (11 February 2017). "Give Indian Navy its due". The Asian Age. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ a b c William Logan. Malabar Manual, Volume 1 Asian Educational Services, 1887

- ^ Arrival of Muslims and its impact on Kerala history (PDF). p. 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ K. M. Mathew. History of the Portuguese Navigation in India. Mittal Publications, 1988 - Goa, Daman and Diu (India)

- ^ "Portuguese India: History of Portuguese Cochin, Cannanore, Quilon. Malabar (Kerala)". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "Vol06chap01sect07". Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Teotonio R. De Souza. Essays in Goan History Concept Publishing Company, 1989

- ^ AG Noorani "Islam in Kerala". Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ A. Sreedhara Menon. Kerala History and its Makers. D C Books (2011)

- ^ A G Noorani. Islam in Kerala. Books [4] Archived 10 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Roland E. Miller. Mappila Muslim Culture SUNY Press, 2015

- ^ a b "European treaties of Malappuram" (PDF). shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ a b "The English supremacy in Ponnani" (PDF). shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honorable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. p. 176. ISBN 9788131300343.

- ^ "History of Malappuram and the Mappila Revolt | Centre for Vedic and Islamic studies". malappuramtourism.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ K. Madhavan Nair, 'Malayalathile Mappila Lahala,' Mathrubhumi, 24 March 1923.

- ^ "Oldest teak plantation, Conolly's Plot, to reopen after maintenance". Mathrubhumi. 16 May 2017. Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Radhakrishnan, S. Anil (29 December 2012). "'Lifeline' of Malabar turns 125". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "ആ ചൂളംവിളി പിന്നെയും പിന്നെയും..." Mathrubhumi. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Devassy, M. K. (1965). District Census Handbook (2) - Kozhikode (1961) (PDF). Ernakulam: Government of Kerala. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "The 1920 political conference at Manjeri". Deccan Chronicle. 29 June 2016. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Malabar Desiyathayude Idapedalukal. Dr. M. T. Ansari. DC Books

- ^ R. H. Hitch cock, 1983 Peasant revolt in Malabar, History of Malabar Rebellion 1921.

- ^ Madras Mail 17 September 1921, p 8

- ^ ‘particularly strong evidence of the moulding influence of British power structures lies in the rebels constant use of British titles to authority such as Assistant Inspector, Collector, Governor, Viceroy and (less conclusively) King’ The Moplah Rebellion and Its Genesis 184

- ^ ‘The rebel kists’, martial law, tolls, passports and, perhaps, the concept of a Pax Mappila, are to all appearances traceable to the British empire in India as a prototype’ The Moplah Rebellion and Its Genesis, Peoples Publishing House, 1987, 183

- ^ C. Gopalan Nair. Moplah Rebellion, 1921. p. 78. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

He issued passports to persons wishing to get outside his kingdom

- ^ F. B. Evans, ‘Notes on the Moplah Rebellion’, 27 March 1922, p 12.

- ^ (Tottenham, G. F. R., ‘Summary of the Important Events of the Rebellion,’ in Tottenham, Mapilla Rebellion) 1921 dated Sept 15 no 367

- ^ Home (Pol) Department, Government of India, File No. 241/XVI,/1922, Telegram Section, p.3, TNA

- ^ Panikkar, K. N., Against Lord and State: Religion and Peasant Uprisings in Malabar 1836-1921

- ^ 1951 census handbook - Malabar district (PDF). Chennai: Government of Madras. 1953. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Imported (20 June 2018). "Development and bifurcation of Malappuram District". english.madhyamam.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ K. Narayanan (1972). District Census Handbook - Malappuram (Part-C) - 1971 (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "Summer Journey 2011". Time. 21 July 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

Further reading

- K. V. Krishna Iyer, Zamorins of Calicut: From the Earliest Times to A D 1806. Calicut: Norman Printing Bureau, 1938.

- M. G. S. Narayanan, Calicut: The City of Truth Revisited Kerala. University of Calicut, 2006

- A. Sreedhara Menon, A Survey of Kerala History, (1967), Madras, 1991

- S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942), Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language, University of Madras

- William Logan (1887), Malabar Manual (Volume-I), Madras Government Press

- William Logan (1887), Malabar Manual (Volume-II), Madras Government Press

- Charles Alexander Innes (1908), Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-I), Madras Government Press

- Charles Alexander Innes (1915), Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-II), Madras Government Press

- Government of Madras (1953), 1951 Census Handbook- Malabar District (PDF), Madras Government Press