History of Lviv

Lviv (Ukrainian: , L’viv; Polish: Lwów; German: Lemberg or Leopoldstadt[citation needed] (archaic); Yiddish: לעמבערג; Russian: Львов, romanized: Lvov, see also other names) is an administrative center in western Ukraine with more than a millennium of history as a settlement, and over seven centuries as a city. Prior to the creation of the modern state of Ukraine, Lviv had been part of numerous states and empires, including, under the name Lwów, Poland and later the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth; under the name Lemberg,[1] the Austrian and later Austro-Hungarian Empires; the short-lived West Ukrainian People's Republic after World War I; Poland again; and the Soviet Union. In addition, both the Swedes and the Ottoman Turks made unsuccessful attempts to conquer the city.

Early history

Recent archaeological excavations show that the area of Lviv has been populated since at least the 5th century,[2] with the gord at Chernecha Hora Street-Voznesensk Street in Lychakivskyi District attributed to White Croats.[3][4][5][6]

In 981, the Cherven Cities were conquered by Volodymyr the Great and came under the rule of Kyivan Rus, after the Kyiv expedition he again began in the early Piast monarchy of Bolesław the Brave and Mieszko II (1018–1031), and then occupied by the prince of Kyiv, Yaroslav the Wise in 1031.

Halych-Volyn Principality

Lviv was officially founded in 1256 by King Daniel of Galicia in the Ruthenian principality of Halych-Volhynia and named in honour of his son Lev.[7] The toponym may best be translated into English as Leo's lands or Leo's City (hence the Latin name Leopolis).

In 1261, the city was invaded by the Tatars.[8] Various sources relate the events, which range from destruction of the castle through a complete razing of the city. All the sources agree that it was on the orders of the Mongol general Burundai. The Naukove tovarystvo im. Shevchenka of the Shevchenko Scientific Society say that the order to raze the city was given by Burundai as the Galician-Volhynian chronicle states that in 1261 "Said Buronda to Vasylko: 'Since you are at peace with me then raze all your castles'".[9] Basil Dmytryshyn states that the order was implied to be regarding the fortifications as a whole "If you wish to have peace with me, then destroy [all fortifications of] your cities".[10] According to the Universal-Lexicon der Gegenwart und Vergangenheit the city's founder was ordered to destroy the city himself.[11]

After Daniel's death, Lev rebuilt Lviv around the year 1270. By choosing Lviv as his residence,[8] Lev made Lviv the capital of Galicia-Volhynia.[12] The city is first mentioned in the Halych-Volhynian Chronicle, which dates from 1256. As a major trade center, Lviv attracted German, Armenian, and other groups of merchants. The city grew quickly due to an influx of Polish people from Kraków, Poland, after they had suffered a widespread famine there.[11] Around 1280 many Armenians lived in Galicia and were mainly based in Lviv where they had their own Archbishop.[13]

In 1323 the Romanovich dynasty, a local branch of the Rurik Dynasty, died out. The city was inherited by Boleslaus of Masovia the heir to both the Piast dynasty on his father's side, and the Romanovich dynasty on his mother's side. He took the name of "Yuriy" and converted to Eastern Orthodoxy but failed to gain the support of the local nobles and was eventually poisoned by them.

The city was inherited by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1340 and ruled by voivode Dmytro Dedko, the favourite of the Lithuanian prince Lubart, until 1349.[14]

Galicia–Volhynia wars and the Polish Kingdom

After Boleslaus Yuriy of Masovia and Halych death in 1340, the rights to his domain were passed to his fellow Piast dynast and cousin, King Casimir III of Poland. The local nobles elected one of their own, Dmytro Dedko, as ruler, and repulsed a Polish invasion during the wars over the succession of Galicia-Volhynia Principality when King Casimir III undertook an expedition to conquer Lviv in 1340, burning down the old princely castle.[8]

After Dedko's death King Casimir III finally returned and his forces occupied Lviv and the rest of Red Ruthenia in 1349 when Casimir built two new castles.[8] From then on the population was subjected to attempts to both Polonise and Catholicise them.[15]

In 1356 Casimir III imparted upon the city with Magdeburg rights, which implied that all city issues were to be resolved by a city council elected by the wealthy citizens. The city council seal of the 14th century stated Civitatis Lembvrgensis. This started a period of accelerated development: among other facilities the Latin Cathedral was built, around the same time a church was built in the place of today's St. George's Cathedral. Also, new self-government led to the greater growth of the Armenian community that built its Armenian Cathedral in 1363.

After Casimir had died in 1370, he was succeeded by his nephew, King Louis I of Hungary, who in 1372 put Lviv together with the region of Galicia-Volhynia under the administration of his relative Władysław, Duke of Opole.[8] When Władysław retreated from the post of its governor in 1387 Galicia-Volhynia became occupied by the Hungarians, but soon Jadwiga the ruler of Poland, and wife of Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila, invaded and incorporated it into the Polish Crown by Jadwiga of Poland.[8] The city later served as the homage site of some of the vassals of the Kings of Poland.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

As a part of Poland (and later Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) the city was known as Lwów and became the capital of the Ruthenian Voivodeship, which included five regions: Lwów, Chełm (Ukrainian: Kholm), Sanok, Halicz (Ukrainian: Halych) and Przemyśl (Ukrainian: Peremyshl). The city was granted the right of transit and started to gain significant profit from the goods transported between the Black Sea and the Baltic. In the following centuries, the city's population grew rapidly and soon Lwów became a multi-ethnic and multi-religious city as well as an important centre of culture, science, and trade.

The city's fortifications were strengthened, with Lviv becoming one of the most important fortresses guarding the Commonwealth from the south-east. Three archbishoprics were once located in the city: Roman Catholic (est. 1375), Greek Catholic and Armenian Catholic. The city was also home to numerous ethnic populations, including Germans, Jews, Italians, Englishmen, Scotsmen and many others. Since the 16th century, the religious mosaic of the city also included strong Protestant communities. By the first half of the 17th century, the city had approximately 25,000–30,000 inhabitants. About 30 craft organizations were active by that time, involving well over a hundred different specialities.

Decline of the Commonwealth

In the 17th century Lviv was besieged unsuccessfully several times. Constant struggles against invading armies gave it the motto Semper fidelis. In 1649, the city was besieged by the Cossacks under Bohdan Khmelnytsky, who seized and destroyed the local castle. However, the Cossacks did not retain the city and withdrew, satisfying themselves with a ransom. In 1655 the Swedish armies invaded Poland and soon took most of it. Eventually the Polish king Jan II Kazimierz solemnly pronounced his vow to consecrate the country to the protection of the Mother of God and proclaimed Her the Patron and Queen of the lands in his kingdom at Lwów Latin Cathedral in 1656 (Lwów Oath).

The Swedes laid siege to Lviv, but were forced to retreat before capturing it. The following year saw Lviv invaded by the armies of the Transylvanian Duke George I Rákóczi, but the city was not captured. In 1672 Lviv was again besieged by the Ottoman army of Mehmed IV, however the Treaty of Buczacz ended the war before the city was taken. In 1675 the city was attacked by the Ottomans and the Tatars, but King John III Sobieski defeated them on August 24 in what is called the Battle of Lwów. In 1704, during the Great Northern War, the city was captured and pillaged for the first time in its history by the armies of Charles XII of Sweden.

Habsburg Era

18th century

In 1772, following the First Partition of Poland, the city was annexed by Austria and became the capital of the Austrian province called the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria as Lemberg, its Germanic name. Initially the Austrian rule was somewhat liberal. In 1773, the first newspaper in Lviv, Gazette de Leopoli, began to be published. The city grew during the 19th century, increasing in population from approximately 30,000 at the time of Austrian annexation in 1772[16] to 196,000 by 1910[17] and to 212,000 three years later;[18] as a result of this rapid growth in population, poverty in Austrian Galicia became exponentially worse.[19]

In 1784, the Emperor Joseph II reopened the University of Lviv. Lectures were held almost exclusively in Latin, although some lectures, such as Pastoral Theology and Obstetrics, were conducted in Polish. German was used as a second language in some courses, primarily in Medicine. Eventually, the university established a Chair of German Language and German became the main language of instruction. In order to educate a new generation of Greek Catholic priests, the university established the Ruthenian Scientific Institute for non-Latin speaking students in 1787. These students were required to learn Philosophy for two years in their native language, Ruthenian and Polish, before studying Theology in Latin. The importance of the institute declined in 1795 after Austria annexed the Polish city of Kraków, which had an ancient and well-established university. Both schools were merged in 1805, and Lviv lost its status as a university city. However, this short period produced a great deal of intellectual activity such as the work of Johann Wenzel Hann, who from 1792 was a University Rector, eminent lecturer, poet and translator of Polish poetry into German after learning Polish himself. Physician Franz Masoch and his assistant Peter Krausnecker made significant contributions to the development of vaccination and the fight against Smallpox.

Wojciech Bogusławski opened the first public theatre in 1794. Józef Maksymilian Ossoliński founded in 1817 the Ossolineum, a scientific institute. Early in the 19th century the city became the new seat of the primate of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the Archbishop of Kyiv (Kiev), Halych and Rus, the Metropolitan of Lviv.

The early 19th century

In the 19th century, blaming the Polish nobility for the backwardness of the region,[20] the Austrian administration attempted to Germanise the city's educational and governmental functions. The university was closed in 1805 and re-opened in 1817 as a purely German academy, without much influence over the city's life. Most of other social and cultural organizations were banned as well. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries a large influx of Germans and German-speaking Czech bureaucrats gave the city a character that by the 1840s was quite German, in its orderliness and in the appearance and popularity of German coffeehouses.[20] A rivalry developed between the new German elites and the older Polish elites.[20]

The revolution of 1848

The harsh laws imposed by the Habsburg Austrian Empire led to an outbreak of public dissent in 1848. A petition was sent to Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria asking him to re-introduce local self-government, education in Polish and Ukrainian, and granting Polish with a status of official language. Six regiments of National Guards were formed after the fashion of the revolutionaries in Vienna, with one-half Polish and the other half Ukrainian. However, the Polish revolutionaries soon forced the Ukrainian regiments to disband and merge into the Polish ones, thus causing ethnic tensions between the groups.

After the uprising in Vienna was crushed on 2 November 1848, discontent spread among the revolutionaries. Arguments quickly broke out between the National Guard and regular Austrian troops garrisoned in the city. The commander of the garrison, General William Friedrich von Hammerstein, ordered the National Guards confined to their barracks. After repeated violations, Hammerstein ordered the arrest of the officers, and this caused the National Guards to seize the town center and throw up barricades.[21]

On 6 November 1848, the Imperial Austrian Army under the command of General Hammerstein commenced bombardment of the city center for three hours, setting fire to the town hall (Rathaus), as well as the academy building, library, museum, and many streets lined with houses.[22] A committee of public safety composed of prominent residents surrendered to the General that day. A state of siege was put in force, martial law declared, and all houses were subject to search. The terms included the disarming of the Academical Legion, which was composed mostly of students, a reorganization of the National Guards and placed under the General's control, and the registration of all foreigners, as these persons were blamed in the city and many other places for spreading rebellion and discontent.

Developments in the mid-nineteenth century

After the revolution of 1848 the languages of instruction at the university re-introduced Ukrainian and Polish. Around that time a certain sociolect developed in the city known as the Lwów dialect. Considered to be a type of Polish dialect, it draws its roots from numerous other languages besides Polish. Most of the pleas were accepted twenty years later in 1861: a Galician parliament (Sejm Krajowy) was opened and in 1867 Galicia was granted vast autonomy, both cultural and economic. The university was also allowed to start lectures in Polish.

In 1853, it was the first European city to have street lights due to innovations discovered by Lviv inhabitants Ignacy Łukasiewicz and Jan Zeh. In that year kerosene lamps were introduced as street lights, which in 1858 were updated to gas and in 1900 to electricity.

After the so-called Ausgleich of February 1867, the Austrian Empire was reformed into a dualist Austria-Hungary and a slow yet steady process of liberalisation of Austrian rule in Galicia started. From 1873, Galicia was de facto an autonomous province of Austria-Hungary with Polish and, to a much lesser degree, Ukrainian or Ruthenian, as official languages. The Germanisation had been halted and the censorship lifted as well. Galicia was subject to the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy, but the Galician Sejm and provincial administration, both established in Lviv, had extensive privileges and prerogatives, especially in education, culture, and local affairs. In 1894, the city hosted the General National Exhibition.[23] Lviv grew rapidly, becoming the 4th largest in Austria-Hungary, according to the census of 1910. Many Belle Époque public edifices and tenement houses were erected, and buildings from the Austrian period, such as the opera theater built in the Viennese neo-Renaissance style, still dominate and characterize much of the centre of the city.

The close of Habsburg rule

During Habsburg rule Lviv became one of the most important Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish cultural centers. The city, granted the right to send delegates to the imperial parliament in Vienna, drew in many prominent cultural and political leaders, and therefore served as a meeting place of Ukrainian, Polish, Jewish and German cultures. In Lviv, according to the Austrian census of 1910, which listed religion and language, 51% of the city's population were Roman Catholics, 28% Jews, and 19% belonged to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Linguistically, 86% of the city's population used the Polish language and 11% preferred the Ukrainian language.[24]

The province of Galicia became the only part of the former Polish state with some cultural and political freedom, and the city then served as a major Polish political and cultural centre. Lviv was home to the Polish Ossolineum, with the second largest collection of Polish books in the world, the Polish Academy of Arts, the Polish Historical Society, the Polish Theater, and Polish Archdiocese. Similarly, the city also served as an important centre of the Ukrainian patriotic movement and culture, unlike other parts of Ukraine under Russian rule, where, prior to 1905, all publications in Ukrainian were prohibited as part of an intense Russification campaign. The city housed the largest and most influential Ukrainian institutions in the world, including the Prosvita society dedicated to spreading literacy in the Ukrainian language, the Shevchenko Scientific Society, the Dniester Insurance Company and base of the Ukrainian cooperative movement, and it served as the seat of the Ukrainian Catholic Church. Lviv was a major center of Jewish culture, in particular as a center of the Yiddish language, and was the home of the world's first Yiddish-language daily newspaper, the Lemberger Togblat.[25]

20th century

During World War I the city was captured by Aleksei Brusilov's Russian Eighth Army in September 1914. After a brief Russian occupation of Eastern Galicia, it was retaken in June 1915 by Austria-Hungary.[26] With the collapse of the Habsburg Empire at the end of World War I, the local Ukrainian population under the guidance of Yevhen Petrushevych proclaimed Lviv as the capital of the West Ukrainian People's Republic on November 1, 1918.

Polish–Ukrainian conflict

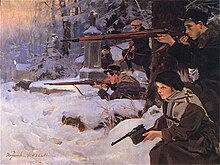

A painting depicting Polish youths in the Lwów Uprising by Poles against the West Ukrainian People's Republic proclaimed in the city.

As the Austro-Hungarian government collapsed, on October 18, 1918, the Ukrainian National Council (Rada) was formed in the city, consisting of Ukrainian members of the Austrian parliament and regional Galician and Bucovinan diets as well as leaders of Ukrainian political parties. The council announced the intention to unite the West Ukrainian lands into a single state. As the Poles were making efforts to take over Lviv and Eastern Galicia, Captain Dmytro Vitovsky of the Sich Riflemen led the group of young Ukrainian officers in a decisive action and during the night of October 31 – November 1, the Ukrainian military men took control over the city. The West Ukrainian People's Republic was proclaimed on November 1, 1918, with Lviv as its capital. The proclamation of the Republic—which claimed sovereignty over largely Ukrainian-populated territories— was a complete surprise for the Poles, who constituted a majority in the city. The Poles considered the territory claimed by the WUPR Polish. So, while the Ukrainian residents enthusiastically supported the proclamation and the city's significant Jewish minority accepted or remained neutral towards the Ukrainian proclamation, the Polish residents were shocked to find themselves in a proclaimed Ukrainian state.[27] Ukrainian soldiers moved to detain the Austrian governor of Galicia, Count Karl von Huyn. The governor staunchly refused to formally hand over power to the Ukrainian National Council. On November 2, Huyn announced that he is no longer able to perform his official duties and handed his authority over to his Ukrainian deputy, Volodymyr Detsykevych, who in turn relinquished his powers to Ukrainian leaders.[28]

Immediately, the Polish majority of Lviv, a city of over 200,000, started an armed uprising that the 1,400 Ukrainian garrison consisting mostly of teenage peasants who were unfamiliar with the city were unable to quell.[27] The Poles soon took control over most of the city centre. Unable to break into the central areas, Ukrainian forces besieged the city, defended by Polish irregular forces including the Lwów Eaglets. After the Inter-Allied Commission in Paris agreed to leave the city under Polish administration until its future was resolved by a post-war treaty or a referendum, the regular Polish forces reached the city on November 19 and by November 22, the Ukrainian troops were forced out. When the Polish forces captured the city, elements of Polish soldiery begun to loot and burn much of the Jewish and Ukrainian quarters of the city, killing approximately 340 civilians (see: Lwów pogrom (1918)).[29] After securing control of Lviv, Polish authorities shut down all Ukrainian institutions and societies, conducted mass arrests of Ukrainians, forced Ukrainians to work on Greek Catholic religious holidays, and dismissed most Ukrainian civil servants. Ukrainian members of the city council resigned in protest, and no Ukrainian would sit on the city council until 1927.[30]

In the following months, other territories of Galicia controlled by the government of the West Ukrainian People's Republic were captured by the Polish forces, which effectively ended the power of the West Ukrainian government. The April 1920 agreement concluded by Poland with Symon Petlura, the exiled leader of the Ukrainian People's Republic, met with the fierce opposition of western Ukrainians. It recognized Poland's control of the city and the area in exchange for Polish military assistance to Petlura against the Bolsheviks.

Polish–Soviet War

During the Polish–Soviet War of 1920 the city was attacked by the Red Army forces of Alexander Yegorov. In mid-June 1920 the 1st Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny was trying to reach the city from the north and east. At the same time Lviv was preparing the defence. The inhabitants raised and fully equipped three regiments of infantry and two regiments of cavalry as well as constructed defensive lines. The city was defended by an equivalent of three Polish divisions aided by one Ukrainian infantry division. Finally after almost a month of heavy fighting on August 16 the Red Army crossed the Bug river and, reinforced by additional 8 divisions of the so-called Red Cossacks, started an assault on the city. The fighting occurred with heavy casualties on both sides, but after three days the assault was halted and the Red Army retreated. For the heroic defence the city was awarded with the Virtuti Militari medal.

Interbellum

Following the Peace of Riga the city remained in Poland as the capital of the Lwów Voivodeship. The city, which was the third biggest in Poland, became one of the most important centres of science, sports and culture of Poland. For example, the Lwów School of Mathematics embodied a rich mathematical tradition; the school gathered at the Scottish Café and maintained a notebook of problems and results.

Population of Lwów, 1931 (by religion)

| Roman Catholic: | 157,500 | (50.4%) |

| Judaism: | 99,600 | (31.9%) |

| Greek Catholic: | 49,800 | (16.0%) |

| Protestant: | 3,600 | (1.2%) |

| Orthodox: | 1,100 | (0.4%) |

| Other denominations: | 600 | (0.2%) |

| Total: | 312,200 |

Source: 1931 Polish census

Population of Lwów, 1931 (by first language)

| Polish: | 198,200 | (63.5%) |

| Yiddish or Hebrew: | 75,300 | (24.1%) |

| Ukrainian or Ruthenian: | 35,100 | (11.2%) |

| German: | 2,500 | (0.8%) |

| Russian: | 500 | (0.2%) |

| Other denominations: | 600 | (0.2%) |

| Total: | 312,200 |

Source: 1931 Polish census

During the interbellum period Lwów had grown significantly from 219,000 inhabitants in 1921, to 312,200 in 1931 and an estimated number of 318,000 residents in 1939. Although Poles constituted a majority, Jews formed more than a one-fourth of population. Ukrainian minority was also sizable one. There were also other minorities, including Germans, Armenians, Karaims, Georgians etc. Though their numbers may not have been numerically significant, their presence nonetheless enriched and enhanced Lwów's multicultural character and heritage. The city was, right after the capital of Warsaw, the second most important cultural and academic centre of Poland (in academical year 1937/38 there were 9,100 students, attending 5 higher education facilities including widely renowned university and institute of technology).[31] Together with Poznań, Lwów was Poland's trade fairs centre, with the internationally renowned Targi Wschodnie (The Eastern Trade Fair) held annually since 1921, which had fostered the city's economic growth.

At the same time, the Polish government reduced the rights of the local Ukrainians, closing down many of the Ukrainian schools.[32] Other schools were turned into bilingual ones by the Polish government that were, in effect, Polish. Increased Polish settlement reduced the relative percentage of the Ukrainian population in the city, from around 20% in 1910 to less than 12% by 1931. At the university, all Ukrainian departments that had opened during the period of Austrian rule were closed save for one, the 1848 Department of Ruthenian Language and Literature, whose chair position was allowed to remain vacant until 1927 before being filled by an ethnic Pole.[33] Most Ukrainian professors were fired, and entrance of ethnic Ukrainians was restricted; in response an underground university in Lwów, and a Ukrainian Free University in Vienna (later moved to Prague)[34] were established.[35] In official documents, the Polish authorities also replaced all references to Ukrainians with the old word "Ruthenians", an action that caused many Ukrainians to view their original self-designation with distaste.[36]

The Polish government also sought to emphasize the city polskość or Polish character. Unlike in Austrian times, when the size and number of public parades or other cultural expressions such as parades or religious processions corresponded to each cultural group's relative population, during Polish rule limitations were placed on public displays of Jewish and Ukrainian culture. Obrona celebrations, dedicated to the Polish defence of Lviv, became a major Polish public celebration, and were integrated by the Roman Catholic Church into the traditional All Saints' Day celebrations in early November. Military parades and commemorations of battles at particular streets within the city, all celebrating the Polish forces who fought against the Ukrainians in 1918, became frequent, and in the 1930s a vast memorial monument and burial ground of Polish soldiers from that conflict was built in the city's Lychakiv Cemetery. The Polish government fostered the idea of Lviv as an eastern Polish outpost standing strong against the eastern "hordes."[37]

World War II

Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and the German 1st Mountain Division reached the suburbs of Lviv on September 12 and began a siege. The city's garrison was ordered to hold out at all cost since the strategic position prevented the enemy from crossing into the Romanian Bridgehead. Also, a number of Polish troops from Central Poland were trying to reach the city and organise a defence there to buy time to regroup. Thus a 10-day-long defence of the city started and later became known as yet another Battle of Lwów. On September 19 an unsuccessful Polish diversionary attack under General Władysław Langner was launched. Soviet troops (part of the forces that had invaded on September 17 under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact) replaced the Germans around the city. On September 21 Langner formally surrendered to Soviet troops under Marshal Semyon Timoshenko.[38]

The Soviet and Nazi forces divided Poland between themselves and a rigged plebiscite absorbed the Soviet-occupied eastern half of Poland, including Lviv, into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Initially, the Jewish and part of the Ukrainian population who lived in the interwar Poland cheered the Soviet takeover whose stated goal was to protect the Ukrainian population in the area.[39] Depolonisation combined with large scale anti-Polish actions began immediately, with huge numbers of Poles and Jews from Lviv deported eastward into the Soviet Union. About 30 thousand were deported in the beginning of 1940 alone.[40] A smaller percentage of the Ukrainian population was deported as well.

When the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the NKVD spent a week hastily executing prisoners held in the Brygidki and Zamarstynów prisons, where around 8,000 were murdered.

Initially, a great part of the Ukrainian population considered the German troops as liberators after the two years of genocidal Soviet regime, similarly to many Jewish and Ukrainian inhabitants who had earlier welcomed the Soviets as their liberators from the rule of "bourgeois" Poland. City's Ukrainian minority initially associated Germans with the previous Austrian times, happier for Ukrainians in comparison to the later Polish and especially Soviet periods. However, already since the beginning of the German occupation of the city, the situation of the city's Jewish inhabitants became tragic. After being subject to deadly pogroms, the Jewish inhabitants of the area were rushed into a newly created ghetto and then mostly sent to various German concentration camps. The Polish and smaller Ukrainian populations of the city were also subject to harsh policies, which resulted in a number of mass executions both in the city and in the Janowska camp. Among the first to be murdered were the professors of the city's universities and other members of Polish elite (intelligentsia). On June 30, 1941, the first day of the German occupation of the city, one of the wings of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) declared restoration of the independent Ukrainian state. Yaroslav Stetsko proclaimed in Lviv the Government of an independent that "will work closely with the National-Socialist Greater Germany, under the leadership of its leader Adolf Hitler, which is forming a new order in Europe and the world" – as stated in the text of the "Act of Proclamation of Ukrainian Statehood". This was done without pre-approval from the Germans and after 15 September 1941 the organisers were arrested.[41][42][43] Stepan Bandera, Yaroslav Stetsko and others, were arrested by Nazi Einsatzgruppe and sent to Nazi concentration camps, where both of Bandera's brothers were executed. The policy of the occupying power turned quickly harsh towards Ukrainians as well. Some of the Ukrainian nationalists were driven underground, and from that time forward, they fought against the Nazis, but continued also to fight against Poles and Soviet forces (see Ukrainian Insurgent Army).

As the Red Army was approaching the city in 1944, on July 21 the local leadership of the Polish Home Army ordered all Polish forces to rise in an armed uprising (see also Operation Tempest). After four days of the city fights and the advance of the Red Army in the final phase of the Lvov-Sandomierz Operation the city was handed over to the Soviet Union.[44] As before, the Soviet authorities quickly turned hostile to the city's Poles, including the members of the Polish Home Army (whose leaders were subsequently executed by the Soviets), and the genocidal policies restarted.

Following the Soviet takeover the members of Polish resistance were either forcibly conscripted to the Soviet controlled Polish People's Army or imprisoned.[44][45]

Lviv pogroms and the Holocaust

Before the war Lviv had the third-largest Jewish population in Poland, which swelled further to over 200,000 Jews as war refugees entered the city. Immediately after the Germans entered the city, Einsatzgruppen and civil collaborators organized a massive pogrom, which they claimed was in retaliation for the NKVD's earlier killings (though Jews were also killed during the NKVD purge). Many Holocaust scholars attribute much of the killing to the Ukrainian nationalists. However the killers' actual political orientation and relation to the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists is still subject to debate.[46] During the four-week pogrom from the end of June to late July, 1941, nearly 4,000 Jews were murdered. On July 25, 1941, a second pogrom, called "Petliura Days" after Symon Petliura,[47][48] was organized; nearly 2,000 more Jews were killed in Lviv, mostly shot in groups by civilian collaborators after being marched to the Jewish cemetery or to Lunecki prison.

The Lwów Ghetto was established after the pogroms, holding around 120,000 Jews, most of whom were deported to the Belzec extermination camp or killed locally during the following two years. Following the pogroms, Einsatzgruppen killings, harsh conditions in the ghetto, and deportation to the death camps, including the Janowska labor camp located on the outskirts of the city, resulted in the almost complete annihilation of the Jewish population. By the time that the Soviet forces reached the town in 1944, only 200–300 Jews remained.

Simon Wiesenthal (later known as a Nazi-hunter) was one of the most notable Jews of Lviv to survive the war, though he was transported to a concentration camp. Many city residents tried to assist and hide the Jews hunted by the Nazis (despite the death penalty imposed for such acts), like for example Leopold Socha, whose story was told in the 2011 film In Darkness, helped two Jewish families to survive in the sewers, where they were hiding after liquidation of the ghetto.[49] Wiesenthal's memoir, The Murderers Amongst Us, describes how he was saved by a Ukrainian policeman named Bodnar. The Lvivans hid thousands of Jews, many of them were later recognized as Righteous Gentiles. A large effort in saving the members of the Jewish community was organized by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky.

Post-war Soviet period

After the war, despite Polish efforts, the city remained as part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. During the Yalta Conference Soviet General Secretary Joseph Stalin demanded to keep the territory the Soviet Union annexed during its invasion of Poland at the beginning of the war. Although U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to allow Poland to keep Lviv, he and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill reluctantly agreed.[50] Most of the remaining Polish population was expelled to the Polish territories gained from Germany (especially to present day Wrocław) whose German population was respectively expelled or fled in fear of Soviet retribution.

Migrants from Ukrainian-speaking rural areas around the city, as well as from other parts of the Soviet Union arrived, attracted by the city's rapidly growing industrial needs. This population transfer altered the traditional ethnic composition of the city, which was already drastically changed as the Polish, Jewish and German population was displaced or murdered.

With Russification being a general Soviet policy in post-war Ukraine, in Lviv it was combined with the disestablishment of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (see History of Christianity in Ukraine) at the state-sponsored Synod of Lviv, which agreed to transfer all parishes to the recently recreated Ukrainian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church. However, after the death of Joseph Stalin, Soviet cultural policies were relaxed, allowing Lviv, the major centre of Western Ukraine to become a major hub of Ukrainian culture.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the city significantly expanded both in population and size. A number of prominent plants and factories were established or moved from eastern parts of the USSR, together with the worforce. The latter resulted in partial Russification of the city. Among the most notable plants were the bus factory (Lvivsky Avtomobilny Zavod), which produced most of the buses in the Soviet Union and employed upwards of 30,000, TV factory Elektron which made one of the most popular brand of television sets in the country, the front-end loader factory (Avto-Pogruzchik), the Progress shoe factory, confectionery Svitoch, and many others. Each of these employed tens of thousands of workers and were among the largest employers in the region. Most of them survive to this day, although economic difficulties put a drain on their production figures.

In the period of Soviet liberalization of the mid-to-end 1980s until the early 1990s (see Glasnost and Perestroika) the city became the centre of Rukh (People's Movement of Ukraine), a political movement advocating Ukrainian independence from the USSR.

Independent Ukraine

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Lviv became part of the newly independent Ukraine, serving as the capital of the Lviv Oblast. Today the city remains one of the most important centers of Ukrainian cultural, economic and political life and is noted for its beautiful and diverse architecture. In its recent history, Lviv strongly supported Viktor Yushchenko during the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election and played a key role in the Orange Revolution. Hundreds of thousands of people would gather in freezing temperature to demonstrate for the Orange camp. Acts of civil disobedience forced the head of the local police to resign and the local assembly issued a resolution refusing to accept the fraudulent first official results.[51]

Lviv celebrated its 750th year in September 2006. One large event was a light show around the Lviv Opera House.

Since the onset of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Lviv has been hit by repeated missile and aerial attacks by the Russian military. Military targets and infrastructure targets were attacked, but there were victims among civilian population and some residential buildings were hit -most recently in December 2023.[52][53]

See also

References

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Я. Ісаєвич, М. Литвин, Ф. Стеблій / Iсторія Львова. У трьох томах (History of Lviv in Three Volumes). Львів : Центр Європи, 2006. – Т. 1, p7. ISBN 978-966-7022-59-4.

- ^ Hrytsak, Yaroslav (2000). "Lviv: A Multicultural History through the Centuries". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 24: 48. JSTOR 41036810. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ Korčinskij, Orest (2006a). "Bijeli Hrvati i problem formiranja države u Prikarpatju" [Eastern Croats and the problem of forming the state in Prykarpattia]. In Nosić, Milan (ed.). Bijeli Hrvati I [White Croats I] (in Croatian). Maveda. p. 37. ISBN 953-7029-04-2.

- ^ Korčinskij, Orest (2006b). "Stiljski grad" [City of Stiljsko]. In Nosić, Milan (ed.). Bijeli Hrvati I [White Croats I] (in Croatian). Maveda. pp. 68–71. ISBN 953-7029-04-2.

- ^ Hupalo, Vira (2014). Звенигородська земля у XI–XIII століттях (соціоісторична реко-нструкція) (in Ukrainian). Lviv: Krypiakevych Institute of Ukrainian Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. p. 77. ISBN 978-966-02-7484-6.

- ^ Orest Subtelny. (1988) Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p. 62

- ^ a b c d e f Meyers Konversations-Lexikon. 6th edition, vol. 12, Leipzig and Vienna 1908, p. 397-398.

- ^ Vasylʹ Mudryĭ, ed. (1962). Naukove tovarystvo im. Shevchenka - Lviv: a symposium on its 700th anniversary. Shevchenko Scientific Society (U.S.). p. 58. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

on the occasion of the demand of the baskak of the Tatars, Burundai, that the prince Vasylko and Lev raze their cities said Buronda to Vasylko: 'Since you are at peace with me then raze all your castles'

- ^ Basil Dmytryshyn (1991). Medieval Russia: a source book, 850-170. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-03-033422-1. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ a b Universal-Lexikon der Gegenwart und Vergangenheit (edited by H. A. Pierer). 2nd edition, vol. 17, Altenburg 1843, pp. 343-344.

- ^ B.V. Melnyk, Vulytsiamy starovynnoho Lvova, Vyd-vo "Svit" (Old Lviv Streets), 2001, ISBN 966-603-048-9

- ^ Allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Wissenschaft und Künste, edited by Johann Samuel Ersch and Johann Gottfried Gruber. Vol. 5, Leipzig 1820, p. 358, footnote 18) (in German).

- ^ André Vauchez; Michael Lapidge; Barrie Dobson, eds. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Translated by Adrian Walford. Chicago: Routledge. p. 879. ISBN 1-57958-282-6.

- ^ Jacob Caro: Geschichte Polens. Vol. 2, Gotha 1863, p. 286 (in German, online)

- ^ Tertius Chandler. (1987) Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellon Press

- ^ Hrytsak, Yaroslav (2010). Prorok we własnym kraju. Iwan Franko i jego Ukraina (1856-1886). Warsaw. p. 151.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hrytsak, Yaroslav. "Lviv: A Multicultural History through the Centuries". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 24: 54.

- ^ New International Encyclopedia, Volume 13. Lemberg 1915, p. 760.

- ^ a b c Chris Hann, Paul R. Magocsi.(2005). Galicia: Multicultured Land. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 193

- ^ The Gardeners' Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette, 18 November 1848, page 871.

- ^ Catherine Edward, Missionary Life Among the Jews in Moldavia, Galicia and Silesia, 1867, page 177.

- ^ "The General Regional Exhibition of Galicia". Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ "Lemberg". New International Encyclopedia, Volume 13. 1915. p. 760

- ^ Paul Robert Magocsi. (2005)Galicia: a Multicultured Land. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp.12-15

- ^ Robson, Stuart (2007). The First World War. Internet Archive (1 ed.). Harrow, England: Pearson Longman. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4058-2471-2.

- ^ a b Orest Subtelny, Ukraine: A History, pp. 367–368, University of Toronto Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8020-8390-0

- ^ Mick, Christoph (2016). Christoph Mick "Lemberg, Lwów, L'viv, 1914–1947. Violence and Ethnicity in a Contested City". Purdue University Press. pp. 144, 146. ISBN 978-1557536716.

- ^ Norman Davies. "Ethnic Diversity in Twentieth Century Poland." In: Herbert Arthur Strauss. Hostages of Modernization: Studies on Modern Antisemitism, 1870–1933/39. Walter de Gruyter, 1993.

- ^ Christoph Mick. (2015). Lemberg, Lwow, Lviv, 1914–1947: Violence and Ethnicity in a Contested City. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, pg. 176

- ^ Mały Rocznik Statystyczny 1939 (Polish statistical yearbook of 1939), GUS, Warsaw, 1939

- ^ Magoscy, R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Ukrainian Free University website Archived 2006-04-23 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed July 30, 2006

- ^ Wood, Elizabeth A. (1990). "Feminists Despite Themselves: Women in Ukrainian Community Life, 1884-1939. By Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak. Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta, 1988. xxv, 460 pp. Plates. Cloth". Slavic Review. 49 (3): 477–478. doi:10.2307/2500020. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2500020.

- ^ Paul R. Magocsi. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 638

- ^ Paul Robert Magocsi. (2005)Galicia: a Multicultured Land. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp.144-145

- ^ The Fate of Poles in the USSR 1939–1989 by Tomasz Piesakowski ISBN 0-901342-24-6 Page 36

- ^ Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1988). "Ukrainian Collaborators". Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. McFarland. pp. 177–259. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

How are we ... to explain the phenomenon of Ukrainians rejoicing and collaborating with the Soviets? Who were these Ukrainians? That they were Ukrainians is certain, but were they communists, Nationalists, unattached peasants? The Answer is "yes" – they were all three

- ^ Sowa, Andrzej L. (1998). Stosunki polsko-ukraińskie 1939–1947 (in Polish). Kraków. p. 122. OCLC 48053561.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Організація українських націоналістів і Українська повстанська армія. Інститут історії НАН України.2004р Організація українських націоналістів і Українська повстанська армія,

- ^ І.К. Патриляк. Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940–1942 роках. — Університет імені Шевченко \Ін-т історії України НАН України Київ, 2004 [ISBN unspecified]

- ^ ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 ISBN 966-02-2535-0

- ^ a b Bolesław Tomaszewski; Jerzy Węgierski (1987). Zarys historii lwowskiego obszaru ZWZ-AK. Warsaw: Pokolenie. p. 38.

- ^ Norman Davies (2004). Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw. Viking Books. p. 784. ISBN 0-670-03284-0.

- ^ Gitelman, Zvi (2001). "The Holocaust". A Century of Ambivalence: The Jews of Russia and the Soviet Union, 1881 to the Present. Indiana University Press. pp. 115–143. ISBN 0-253-21418-1.

The facts remain that in Lvov, two days after the Germans took over, a three-day pogrom by Ukrainians resulted in the killing of 6,000 Jews, mostly by uniformed Ukrainian "militia", in the Brygidky prison. July 25 was declared "Petliura Day", after the Ukrainian leader of the Civil War period who was assassinated by the son of the Jewish pogrom victims. Over 5,000 Jews were hunted down and most of them killed in honor of the "celebration." Emigres from Ukraine and Ukrainians from Poland were in the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), which pledged Hitler its "most loyal obedience" in building a Europe "free of Jews, Bolsheviks and plutocrats.

- ^ "Lvov". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "July 25: Pogrom in Lvov". Chronology of the Holocaust. Yad Vashem. 2004. Retrieved August 27, 2006.

- ^ "Angels in the Dark". 9 May 2009.

- ^ Reynolds, David (2009). Summits : six meetings that shaped the twentieth century. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-4458-9. OCLC 646810103.

- ^ Tchorek, Kamil (November 26, 2004). "Protest grows in western city". Times Online. London. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Lytvynova, Polina (December 29, 2023). "See the aftermath of Russia's aerial assault on several cities in Ukraine". National Public Radio. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ "Russia launches air attacks against Ukraine's western Lviv city". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2023-12-29.