History of Lowell, Massachusetts

The history of Lowell, Massachusetts, is closely tied to its location along the Pawtucket Falls of the Merrimack River, from being an important fishing ground for the Pennacook tribe[1] to providing water power for the factories that formed the basis of the city's economy for a century. The city of Lowell was started in the 1820s as a money-making venture and social project referred to as "The Lowell Experiment", and quickly became the United States' largest textile center. However, within approximately a century, the decline and collapse of that industry in New England placed the city into a deep recession. Lowell's "rebirth", partially tied to Lowell National Historical Park, has made it a model for other former industrial towns, although the city continues to struggle with deindustrialization and suburbanization.

Lowell is considered the "Cradle of the American Industrial Revolution",[2] as it was the first large-scale factory town in the United States.

Pre-colonial history and founding

The area around what is now Lowell was an important hub for the Pennacook Indians.[3] The land above the Pawtucket Falls on the northern bank of the Merrimack was inhabited by the Pawtucket group, while the land along both sides of the Concord River was inhabited by the Wamesits. The site of Lowell itself (and a portion of Dracut) served as the location of both the Pawtucket and Wamesit capitals,[4] primarily due to the availability of salmon at Pawtucket Falls and the transportation system provided by the local network of rivers. At the time that the colonists first substantively encountered the tribes, Daniel Gookin that they had a combined population of 12,000, with 3,000 living in the capital.[5]

The first interactions between the colonists and the Pawtucket group occurred through trade and religious conversion. During the 1640s, Major Simon Willard traded extensively with the tribes, and in 1647 was accompanied in his expedition by the noted preacher John Eliot. Eliot returned a year later, and quickly founded a church there with a native convert named Samuel as the pastor.[6] A dedicated church building was built in 1653, remaining until 1824, when it was demolished.[7] Colonists began to move closer to the native tribes with the founding of Chelmsford in 1653.[8] Subsequent grants of land extended the town to cover most of the territory Lowell now occupies, with the exception of 500 acres of farmland reserved for the Pawtucket.[9] The colonists began actively buying land from the Pawtucket, trading those 500 acres for the island of Wickassee above the Pawtucket Falls,[10] and the hysteria generated by King Philip's War weakened both the tribe and its relations with the colonists.[11][12]

By the time the war ended in 1676, the community was much reduced. Wannalancit, the son of Passaconaway and the Pawtucket leader after his father's retirement, took the surviving tribesmen and moved to Wickassee before selling the land in 1686. The tribe moved to Canada, wandering with the Abenaki before briefly returning in 1692 to negotiate with tribes on behalf of Chelmsford during King William's War.[13] The final parts of Pawtucket territory were finally purchased in the early 18th century, with a deed issued in 1714 removing their last legal claim and the annexation of "Indian town" in 1726.[14] With that, what is now Lowell became entirely colonist-owned, existing as part of the towns of Chelmsford and Dracut.[15]

Early industrialization

Entrepreneurs and industrialists soon began using Chelmsford as a location for new mills and manufacturing plants. The presence of Pawtucket Falls offered a source of water power that enabled the construction of a sawmill and gristmill in the early 18th century,[14] followed by a fulling mill in 1737.[16] The region's forests made it an attractive area for logging, but necessitated a way of shipping lumber down the river. The Pawtucket Falls made this difficult, as they included a 32-foot drop.[17] In 1792, the Proprietors of Locks and Canals association was formed, and completed a canal to bypass Pawtucket Falls in 1797.[18] This would allow the shipping of lumber and other products to the shipyards at Newburyport. Unfortunately the creation of the Middlesex Canal, which formed a direct route to Boston, severely harmed the Pawtucket Canal's prospects, and it swiftly fell into disuse.[19]

Francis Cabot Lowell, an American businessman and textile merchant, visited Britain in 1810 to investigate their textile machinery. Because British law prohibited the export of the machines, Lowell instead memorized the designs, and on his return helped build a replica. In 1813 he organised the Boston Manufacturing Company and created a cotton mill in Waltham, Massachusetts. This mill was the first one in America to use power looms, and proved so successful that Patrick Jackson (Lowell's successor after his death in 1817) saw a need to open a new plant.[20] Waltham had been chosen due to the power provided by the Charles River, and Jackson chose to use Pawtucket Falls to power the second plant. The creation of the canal did, however, provide Chelmsford with a convenient source of water for manufacturing purposes; a series of small cotton and gunpowder manufacturing businesses sprung up, using the canal as a water power source.[21]

Jackson and others founded the Merrimack Manufacturing Company to open a mill by Pawtucket Falls, breaking ground in 1822 and completing the first run of cotton in 1823.[22] Within two years a need for more mills and machinery became evident, and a series of new canals were dug, allowing for even more manufacturing plants.[23] With a growing population and booming economy, Lowell was finally spun off from Chelmsford. Named after Francis Cabot Lowell, it was officially chartered on March 1, 1826, with a population of 2,500.[24] Within a decade the population jumped from 2,500 to 18,000, and on April 1, 1836, the town of Lowell officially received a charter as a city, granted by the Massachusetts General Court.[25]

City of Lowell

Lowell was only the third Massachusetts community to be granted city government, after Boston and Salem. The population at the time was 17,633, and soon, a court, jail, hospital, cemetery, library, and two town commons were established. The first museums and theatres opened around 1840. Lowell also began annexing neighboring areas, including Belvidere from Tewksbury in 1834, and Centralville from Dracut in 1851. Daniel Ayer started the satellite city of Ayer's City in South Lowell in 1847, and in 1874, Pawtucketville and Middlesex Village were annexed from Dracut and Chelmsford respectively, bringing the city close to its present borders.

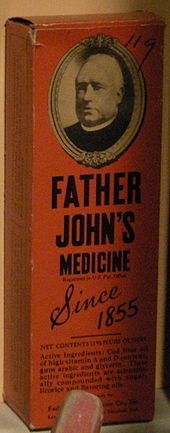

By 1850, Lowell's population was 33,000, making it the second largest city in Massachusetts and America's largest industrial center. The 5.6 mile long canal system produced 10,000 horsepower, being provided to ten corporations with a total of forty mills. Ten thousand workers used an equal number of looms fed by 320,000 spindles. The mills were producing 50,000 miles of cloth annually. Other industries developed in Lowell as well: The Lowell Machine Shop and Father John's Medicine opened. Tanneries, a bleachery, and service companies needed by the growing city were established. Moxie, an early soft drink, was invented in Lowell in the 1870s. Around 1880, Lowell became the first city in America to have telephone numbers.

Lowell continued to be in the forefront of new industrial technology. In 1828, Paul Moody developed an early belt-driven power transfer system to supersede the unreliable gearwork that was utilized at the time. In 1830, Patrick Tracy Jackson commissioned work on the Boston and Lowell Railroad, one of the Oldest railroads in North America. It opened five years became independent in 1845, patent medicine factories like Hood's Sarsaparilla Laboratory later, making the Middlesex Canal obsolete. Soon, lines up the Merrimack to Nashua, downriver to Lawrence, and inland to Groton Junction, today known as Ayer (renamed after Lowell patent medicine tycoon Dr. James Cook Ayer), were constructed.

Uriah A. Boyden installed his first turbine in the Appleton Mill in 1844,[26] which was a major efficiency improvement over the old-fashioned waterwheel. The turbine was improved at Lowell again shortly thereafter by Englishman James B. Francis, chief engineer of Proprietors of Locks and Canals. Francis had begun his career with Locks and Canals working under George Washington Whistler, the father of painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and his improved turbine, known as the Francis Turbine, is still used with few changes today.

Francis also designed the Francis Gate, a flood control mechanism that provides a means of sealing the canal system off from the Merrimack River, and completed the canal system by adding the Northern Canal and Moody Street Feeder, both designed to improve efficiency to the entire system. To further improve the amount of year-round, day and night water power Lowell needed, Francis, along with engineers from Lawrence, were involved with The Lake Company, a corporation involved in building dams in the Lakes Region of Central New Hampshire. These dams, constructed and improved mid-century, allowed the cities on the Merrimack River to store and release water from the Merrimack's source, including Lake Winnipesaukee.[27]

In the late 19th century, new technologies changed Lowell. The electric streetcar allowed the city to expand creating new neighborhoods on the outskirts. Tyler Park and Lynde Hill in Belvidere were home to many of Lowell's wealthiest residents, who could now live away from the noisy and polluted downtown industrial area. The prosperous city built a massive new Romanesque city hall made of granite with a clock tower that could be seen from the mill-yards. A new library with a hall dedicated to the Civil War, a post office, and ornate commercial buildings replaced the puritanical mid-century structures.

Steam power was first used to supplement the fully developed hydropower sources in Lowell in the 1860s, and by the mid-1870s, it was the dominant energy source. Electricity allowed the mills to run on hydroelectricity, instead of direct-drive hydropower. These improvements allowed Lowell to continue increasing its industrial output with a lesser increase in the number of workers. However, the move away from pure hydropower was leading to Lowell being eclipsed by cities with better locations for the new power sources. For example, in the 50 years after the Civil War, Fall River, Massachusetts and New Bedford, Massachusetts both became larger factory towns than Lowell based on output. The reason was largely because their seaport locations made the importation and exportation of goods and materials, and particularly coal, more economical than the considerably inland, and therefore only accessible by train, Lowell. By 1920, it was being seriously suggested that the Merrimack be dredged from Newburyport to Lowell so that barges could access the city.[28] However, the events of the 1920s ensured that would never happen.

In 1885 was founded the Lowell Co-operative Bank, today Sage Bank, one of the oldest still functioning banks in Massachusetts.[29]

Immigration

Being a booming city with many low-skilled jobs, waves of immigrants came into Lowell to work the mills. The original 30 Irish that came to help build the canals were led by Hugh Cummiskey along the Middlesex canal from Charlestown to Pawtucket Falls on foot April 6, 1822. They were met by Kirk Boott and given a pittance. No allowance was made for housing or other provisioning.[30] These were followed by a new group after the Great Famine of Ireland, and later Catholic Germans. These Irish were herded onto land that was not under the control of the mills into an area now called "The Acre," but at that point called "Paddy Camp Lands."[31][page needed] Ethnic tensions—sometimes stoked by mill companies seeking to use members of one community as strikebreakers against members of another—were not unheard of, and in the 1840s, the nativist, anti-Catholic American Party (often called the Know-Nothing Party) won elections in Lowell.[32] By the 1850s, industry competition increased as more manufacturing centers were built elsewhere, Lowell's mills employed increasing numbers of immigrant families, and the early "Lowell System" of Yankee women workers living in company boardinghouses was transformed. In its place, large, densely populated ethnic neighborhoods grew around the city, their residents more rooted in their churches, organizations, and communities than the previous era's company boardinghouse dwellers.

The American Civil War shut down many of the mills temporarily when they sold off their cotton stockpiles, which had become more valuable than the finished cloth after imports from the South had stopped. Many jobs were lost, but the effect was somewhat mitigated by the number of men serving in the military. Lowell had a small historical place in the war: Many wool Union uniforms were made in Lowell, General Benjamin Franklin Butler was from the city, and members of the Lowell-based Massachusetts Sixth—Ladd, Whitney, Taylor, and Needham—were the first four Union deaths, killed in a riot while passing through Baltimore on their way to Washington, DC. Ladd, Whitney, and later Taylor are buried in front of City Hall under a large obelisk.

After the war, mills returned to life. Recruiters fanned out all over New England for help. New mill hands were often new widows, mothers in single parent families. By August 1865, this source dried up.[33]

New immigrant groups moved into the city. In the 1870s and 1880s, French Canadians began moving into an area which became known as Little Canada. Later French Canadian immigrants included the parents of famed Beat generation writer Jack Kerouac, a native of the city. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the early 20th century, Greeks moved into the sections of the old Irish Acre. Other Groups such as the Portuguese, Polish, Lithuanians, Jews, Swedes, Finns, Norwegians, and many other immigrant groups came to work in Lowell and settled their own neighborhoods throughout Lowell. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, approximately 50 percent of Lowell's 112,000 residents were foreign born.[34]

Decline

By the 1920s, the New England textile industry began to shift South and many of Lowell's textile mills began to move or close. Although the South did not have rivers capable of providing the waterpower needed to run the early mills, the advent of steam-powered factories allowed companies to take advantage of the cheaper labor and transportation costs available there. Labor strikes in the North became more frequent, and severe ones like the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike in neighboring Lawrence were driving up costs for investors. Many textile companies changed to a policy of disinvestment, running the mills with no capital improvements until they were no longer capable of producing profit that could be used to build or improve new factories elsewhere. In 1916, the Bigelow Carpet Company, which had previously purchased the Lowell Manufacturing Company, left Lowell. This was the first of the major corporations to move operations to the South or go bankrupt. World War I briefly improved the situation, but from 1926 to 1929, most of the rest of the companies, including the Lowell Machine Shop (which had become the Saco-Lowell Shops) left the city: The Great Depression had come to Lowell early. In 1930, Lowell's population was slightly over 100,000, down from a high of 112,000 a decade earlier. The textile industry employed 8,000 in 1936, it had been 17,000 in 1900. By the onset of World War II, 40% of the city's population was on relief. World War II again briefly helped the economy, since not only did demand for clothing go up, but Lowell was involved in munitions manufacturing. After the war, things cooled again. In 1956, the Boott Mills closed, and after over 130 years, the Merrimack Manufacturing Company closed in 1958.

Bottoming out

By the mid-1970s, Lowell's population had fallen to 91,000, and 12% of residents were unemployed. The industrial economy of the city had been reduced to many smaller scale, marginal businesses. The city's infrastructure and buildings were largely over one hundred years old, obsolete and decaying, often abandoned and in foreclosure. Urban renewal demolished many historic structures in a desperate attempt to improve the overall situation in Lowell. In 1939, the Greek Acre was the first district in the nation to face "slum clearance" with Federal Urban Renewal money. In the late 1950s, Little Canada was bulldozed. In 1960, the Merrimack Manufacturing Company's millyard and boardinghouses were demolished to make way for warehouses and public housing projects. Other neighborhoods like Hale-Howard between Thorndike and Chelmsford Streets, and an area between Gorham and South Streets, were cleared as well. Arson became a serious issue, and crime in general rose. Lowell's reputation suffered tremendously.

As the car took over American life after World War II, the downtown, which already was facing problems due to a drop in expendable income, was largely vacated as business moved to suburban shopping malls. The theatres and department stores left, and much smaller enterprises moved in if anything. Many buildings were torn down for parking lots, and many others burned down, and were not replaced. Others had their top floors removed to reduce tax bills and many facades were "modernized" destroying the Victorian character of the downtown. Road widening and other improvements destroyed a row of business next to city hall, as well as the area that has become the Lord Overpass. The construction of the Lowell Connector around 1960 was surprisingly unintrusive for an urban interstate, but that was only because plans to extend it to East Merrimack Street by way of Back Central and the Concord Riverfront were cancelled. Talk began on filling in the canals to make more real estate.

Officials described the city as looking like Europe after World War II. However, the demolition and decay of much of what had made Lowell a vibrant city led some residents to begin thinking about saving the historical structures.

National Park

Lowell, even as far back as the 1860s, was described by local historian Charles Cowley as a city with little civic pride. At the time, Cowley attributed it to a large percentage of the population being foreign born and therefore having no real roots there. Post its industrial collapse, that sentiment intensified, even if the reasons had changed. Many residents of Lowell viewed the city's industrial history poorly - the factories had abandoned their workers, and now sat empty and in disrepair. However, some city residents, such as educator Patrick J Mogan, viewed the city's history as something that should be preserved and capitalized on. In 1974, Lowell Heritage State Park was founded, and in 1978, Lowell National Historical Park was created as an urban national park, through legislation filed by Lowell native, congressman, and later senator Paul Tsongas. The canal system, many mills, and some commercial structures downtown were saved by the creation of the park and the visitors it brought.

The Massachusetts Miracle brought new jobs and money to the city in the 1980s. Wang Laboratories became a major employer, and built their world headquarters on the edge of the city. After the Vietnam War and the Khmer Rouge rule of Cambodia, many Southeast Asians, and particularly Cambodians moved into the city. Lowell became the largest Cambodian community on the east coast, and second nationally to Long Beach, California.[35] Combined with other immigrant groups like Puerto Ricans, Greeks and French Canadians, these newcomers brought the city's population back up to six figures. However, this prosperity was short-lived. By 1990, the Massachusetts Miracle was over, Wang had virtually disappeared, and even more of Lowell's long-established businesses failed. Around this time, the last large department store left downtown Lowell, largely blamed on suburban factors,[36] including a large mall built a short drive away in tax-free New Hampshire in the mid-1980s,[37] followed by another large mall, also a short drive away and in New Hampshire, in the early 1990s.[38] Additionally, gang violence and the drug trade had become severe.[citation needed] The HBO special, High on Crack Street: Lost Lives in Lowell was filmed in 1995 which tended to emphasize the reputation of the city as a dangerous and depressed place to be.[citation needed]

Modern era

Aside from the National Historical Park, Lowell is a functioning modern city of over 100,000 residents. Numerous initiatives have taken place over the last fifteen years to re-focus the city away from manufacturing, and towards a post-industrial economy.

Community Development

New groups have moved into Lowell's neighborhoods, including Brazilians and Africans,[39][40] continuing Lowell's traditional role as a melting pot.

A project that will redevelop land once held by the Saco-Lowell Shops and the Hamilton and Appleton Mills was underway in 2009.[41] Numerous projects are being undertaken around the city, to beautify and redevelop decaying areas.[42]

Tourism and Entertainment

The Tsongas Center at UMass Lowell and LeLacheur Park were constructed in 1998. Lowell Devils hockey and Lowell Spinners baseball farm teams came to the city. National circuit entertainment is performed at the arena and at the old Lowell Memorial Auditorium. The Lowell Folk Festival, the largest free folk festival in the country, is an annual event.

The National Park has continued to expand; many buildings are still being rehabilitated.

After Massachusetts started offering a tax credit to those who film in the Commonwealth, a few movies have been made in Lowell. The Invention of Lying was released in September 2009, and shortly before, filming on The Fighter, about Lowell boxing legend Micky Ward and his older brother Dicky Eklund, was completed.

Education

The University of Massachusetts Lowell and Middlesex Community College are playing increasingly larger roles in the city. In 2009, UMass Lowell bought up the underutilized Doubletree hotel for use as a dormitory, increasing their presence in the city's downtown.[43]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "Lowell History". lowell.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ Ridgley, Heidi (Spring 2009). "An Industrial Revolution". National Parks Magazine. American National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 22, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2009.

- ^ Citizen-Courier Company 1897, p. 64.

- ^ Citizen-Courier Company 1897, p. 65.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 12.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 17.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 18.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 20.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 22.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 35.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 40-41.

- ^ Citizen-Courier Company 1897, p. 95.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 43.

- ^ a b Citizen-Courier Company 1897, p. 97.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 46.

- ^ Coburn 1920, p. 65.

- ^ Miles 1972, p. 13.

- ^ Marion, Paul (September 8, 2014). Mill Power: The Origin and Impact of Lowell National Historical Park. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442236301.

- ^ Miles 1972, p. 14-16.

- ^ Eno 1976, p. 72.

- ^ Miles 1972, p. 18-19.

- ^ Miles 1972, p. 29.

- ^ Eno 1976, p. 73-4.

- ^ Eno 1976, p. 91.

- ^ Eno 1976, p. 95.

- ^ Appleton's Dictionary of Machines, Mechanics, Enginework, and Engineering, Volume 2 (Google eBook) D. Appleton & Company, 1869 Page 882

- ^ Pursell, Carroll W. (2001). American Technology. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 42–46. ISBN 0-631-21997-8.

- ^ Frederick Coburn, History of Lowell and its People V1

- ^ "LowellBank Announces Intention To Change Name To Sage Bank". PR Newswire. May 16, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ Eno 1976, p. 190.

- ^ Eno 1976.

- ^ Dublin, Thomas (1992). "Immigrant Lowell". Lowell: The Story of an Industrial City. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service Division of Publications. pp. 65–76.

- ^ Gordon, Wendy M (February 2007). Ella Bailey: A Mill Girl at Home-Part 2. Vermont's Northland Journal.

- ^ "Lowell History Chronology". Lowell Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 9, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ Tuon, Bunkong. "The Politics of Identity". Khmer Institute. Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ^ "Downtown Lowell Strategic Plan: Introduction". Lowell Center City Committee. Lowell Division of Planning and Development. November 16, 2000. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Lowell, MA to Pheasant Lane Mall, Nashua, NH". Google Maps. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ "Lowell, MA to The Mall at Rockingham Park, Salem, NH". Google Maps. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Spoth, Tom (November 13, 2006). "From Rio to Lowell". The Sun. Lowell, MA: Digital First Media. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ Lewis, Brendan (June 28, 2015). "Festival spreads growing African culture". The Sun. Lowell, MA: Digital First Media. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ "Hamilton Canal Innovation District". hamiltoncanal.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ "Lowell, MA | Official Website".

- ^ Scott, Christopher (June 9, 2009). "UML Purchases DoubleTree Hotel". Press Room at UMass Lowell. Lowell Sun. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

References

- Citizen-Courier Company (1897). Illustrated History of Lowell and Vicinity: Massachusetts. Higginson Book Company.

- Coburn, Frederick William (1920). History of Lowell and Its People. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company.

- Cowley, Charles (September 13, 2006) [1868]. A History of Lowell. Michigan: Scholarly Publishing Office, University of Michigan Library. ISBN 978-1-4255-2201-8.

- Eno, Arthur (1976). Cotton Was King: a History of Lowell, Massachusetts. New Hampshire Publishing Society. ISBN 0912274611.

- Lowell Historical Society (2005). Lowell the Mill City. Portsmouth, NH: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3760-8.

- Miles, Henry A. (1972). Lowell: As It Was, and As It Is. Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-04714-2.

- Prendergast, John (1996). The Bend in the River (Third ed.). Tyngsborough, Massachusetts: Merrimack River Press. ISBN 0-9629338-0-5.

External links

- City of Lowell

- Lowell National Historical Park

- University of Massachusetts Lowell, Center for Lowell History

- Map of Lowell in 1924 Archived June 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Wall & Gray. 1871 Atlas of Massachusetts. Map of Massachusetts. Middlesex County Lowell

- History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Volume 1 (A-H), Volume 2 (L-W) compiled by Samuel Adams Drake, published 1879 and 1880. 572 and 505 pages. Lowell section by Alfred Gilman in volume 2 pages 53–112.