History of Germany (1945–1990)

| |

West Germany |

East Germany |

|---|---|

The history of Germany from 1945 to 1990 comprises the period following World War II. The period began with the Berlin Declaration, marking the abolition of the German Reich and Allied-occupied period in Germany on 5 June 1945, and ended with the German reunification on 3 October 1990.

Following the collapse of the Third Reich in 1945 and its defeat in World War II, Germany was stripped of its territorial gains. Beyond that, more than a quarter of its old pre-war territory was annexed by communist Poland and the Soviet Union. The German populations of these areas were expelled to the west. Saarland was a French protectorate from 1947 to 1956 without the recognition of the "Four Powers", because the Soviet Union opposed it, making it a disputed territory.

At the end of World War II, there were some eight million foreign displaced people in Germany,[1] mainly forced laborers and prisoners. This included around 400,000 survivors of the Nazi concentration camp system,[2] where many times more had died from starvation, harsh conditions, murder, or being worked to death. Between 1944 and 1950, some 12 to 14 million German-speaking refugees and expellees arrived in Western and central Germany from the former eastern territories and other countries in Eastern Europe; an estimated two million of them died on the way there.[1][3][4] Some nine million Germans were prisoners of war.[5]

With the beginning of the Cold War, the remaining territory of Germany was divided between the Western Bloc led by the United States, and the Eastern Bloc led by the USSR. Two separate German countries emerged:

- the Federal Republic of Germany, established on 23 May 1949, commonly known as West Germany, was a parliamentary democracy with an social democratic economic system and free churches and labor unions;

- the German Democratic Republic, established on 7 October 1949, commonly known as East Germany, was a Marxist–Leninist socialist republic with its leadership dominated by the Soviet-aligned Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED).[6]

Under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, West Germany built strong relationships with France, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Israel.[7] West Germany also joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Economic Community. East Germany's economy, centrally planned in the Soviet style, grew increasingly stagnant; the East German secret police tightly controlled daily life, and the Berlin Wall (1961) ended the steady flow of refugees to the West. The country was reunited on 3 October 1990, following the decline and fall of the SED as the ruling party of East Germany and the Peaceful Revolution there.

Division of Germany

Four military occupied zones

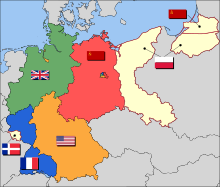

At the Potsdam Conference (17 July to 2 August 1945), after Germany's unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945,[8] the Allies officially divided Germany into the four military occupation zones — France in the southwest, the United Kingdom in the northwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east, bounded on the east by the new Poland-Germany border on the Oder-Neisse line. At Potsdam, these four zones in total were denoted as 'Germany as a whole', and the four Allied Powers exercised the sovereign authority they now claimed over Germany in agreeing 'in principle' to the ceding of territory of the former German Reich east of 'Germany as a whole' to Poland and the Soviet Union.[9]

In addition, under the Allies' Berlin Declaration (1945), the territory of the extinguished German Reich was to be treated as the land area within its borders as of 31 December 1937. All land expansion from 1938 to 1945 was hence treated as automatically invalid, including Eupen-Malmedy, Alsace-Lorraine, Austria, Lower Styria, Upper Carniola, Southern Carinthia, Bohemia, Moravia, Czech Silesia, Danzig, Poland, and Memel.

Flight and expulsion of ethnic Germans

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

The northern half of East Prussia in the region of Königsberg was administratively assigned by the Potsdam Agreement to the Soviet Union, pending a final Peace Conference (with the commitment of Britain and the United States to support its incorporation into Russia); and was then annexed by the Soviet Union. The Free City of Danzig and the southern half of East Prussia were incorporated into and annexed by Poland; the Allies having assured the Polish government-in-exile of their support for this after the Tehran Conference in 1943. It was also agreed at Potsdam that Poland would receive all German lands East of the Oder-Neisse line, although the exact delimitation of the boundary was left to be resolved at an eventual Peace Conference. Under the wartime alliances of the United Kingdom with the Czechoslovak and Polish governments-in-exile, the British had agreed in July 1942 to support "the General Principle of the transfer to Germany of German minorities in Central and South Eastern Europe after the war in cases where this seems necessary and desirable". In 1944 roughly 12.4 million ethnic Germans were living in territory that became part of post-war Poland and Soviet Union. Approximately 6 million fled or were evacuated before the Red Army occupied the area. Of the remainder, around 2 million died during the war or in its aftermath (1.4 million as military casualties; 600,000 as civilian deaths),[10] 3.6 million were expelled by the Poles, one million declared themselves to be Poles, and 300,000 remained in Poland as Germans. The Sudetenland territories, surrendered to Germany by the Munich Agreement, were returned to Czechoslovakia; these territories containing a further 3 million ethnic Germans. 'Wild' expulsions from Czechoslovakia began immediately after the German surrender.

The Potsdam Conference subsequently sanctioned the "orderly and humane" transfer to Germany of individuals regarded as "ethnic Germans" by authorities in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Hungary. The Potsdam Agreement recognized that these expulsions were already underway and were putting a burden on authorities in the German Occupation Zones, including the re-defined Soviet Occupation Zone. Most of the Germans who were being expelled were from Czechoslovakia and Poland, which included most of the territory to the east of the Oder-Neisse Line. The Potsdam Declaration stated:

Since the influx of a large number of Germans into Germany would increase the burden already resting on the occupying authorities, they consider that the Allied Control Council in Germany should in the first instance examine the problem with special regard to the question of the equitable distribution of these Germans among the several zones of occupation. They are accordingly instructing their respective representatives on the control council to report to their Governments as soon as possible the extent to which such persons have already entered Germany from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, and to submit an estimate of the time and rate at which further transfers could be carried out, having regard to the present situation in Germany. The Czechoslovak Government, the Polish Provisional Government and the control council in Hungary are at the same time being informed of the above and are being requested meanwhile to suspend further expulsions pending the examination by the Governments concerned of the report from their representatives on the control council.

Many of the ethnic Germans, who were primarily women and children, and especially those under the control of Polish and Czechoslovakian authorities, were severely mistreated before they were ultimately deported to Germany. Thousands died in forced labor camps such as Lambinowice, Zgoda labour camp, Central Labour Camp Potulice, Central Labour Camp Jaworzno, Glaz, Milecin, Gronowo, and Sikawa.[11] Others starved, died of disease, or froze to death while being expelled in slow and ill-equipped trains; or in transit camps.

Altogether, around 8 million ethnic German refugees and expellees from across Europe eventually settled in West Germany, with a further 3 million in East Germany. In West Germany these represented a major voting block; maintaining a strong culture of grievance and victimhood against Soviet Power, pressing for a continued commitment to full German reunification, claiming compensation, pursuing the right of return to lost property in the East, and opposing any recognition of the postwar extension of Poland and the Soviet Union into former German lands.[12] Owing to the Cold War rhetoric and successful political machinations of Konrad Adenauer, this block eventually became substantially aligned with the Christian Democratic Union of Germany; although in practice 'westward-looking' CDU policies favouring the Atlantic Alliance and the European Union worked against the possibility of achieving the objectives of the expellee population from the east through negotiation with the Soviet Union. But for Adenauer, fostering and encouraging unrealistic demands and uncompromising expectations amongst the expellees would serve his "Policy of Strength" by which West Germany contrived to inhibit consideration of unification or a final Peace Treaty until the West was strong enough to face the Soviets on equal terms. Consequently, the Federal Republic in the 1950s adopted much of the symbolism of expellee groups; especially in appropriating and subverting the terminology and imagery of the Holocaust; applying this to post-war German experience instead.[13] Eventually in 1990, following the Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to Germany, the unified Germany indeed confirmed in treaties with Poland and the Soviet Union that the transfer of sovereignty over the former German eastern territories in 1945 had been permanent and irreversible; Germany now undertaking never again to make territorial claims in respect of these lands.

The intended governing body of Germany was called the Allied Control Council, consisting of the commanders-in-chief in Germany of the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union; who exercised supreme authority in their respective zones, while supposedly acting in concert on questions affecting the whole country. In actuality however, the French consistently blocked any progress towards re-establishing all-German governing institutions; substantially in pursuit of French aspirations for a dismembered Germany, but also as a response to the exclusion of France from the Yalta and Potsdam conferences. Berlin, which lay in the Soviet (eastern) sector, was also divided into four sectors with the Western sectors later becoming West Berlin and the Soviet sector becoming East Berlin.

Elimination of war potential and reparations

Denazification

A key item in the occupiers' agenda was denazification. The swastika and other outward symbols of the Nazi regime were banned, and a Provisional Civil Ensign was established as a temporary German flag. It remained the official flag of the country (necessary for reasons of international law) until East Germany and West Germany (see below) were independently established in 1949.

The United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union had agreed at Potsdam to a broad program of decentralization, treating Germany as a single economic unit with some central administrative departments. These plans never materialized, initially because France blocked any establishment of central administrative or political structures for Germany; and also as both the Soviet Union and France were intent on extracting as much material benefit as possible from their occupation zones in order to make good in part the enormous destruction caused by the German Wehrmacht; and the policy broke down completely in 1948 when the Russians blockaded West Berlin and the Cold War began. It was agreed at Potsdam that the leading members of the Nazi regime who had been captured should be put on trial accused of crimes against humanity, and this was one of the few points on which the four powers were able to agree. In order to secure the presence of the western allies in Berlin, the United States agreed to withdraw from Thuringia and Saxony in exchange for the division of Berlin into four sectors.

Future President and General Dwight D. Eisenhower and the US War Department initially implemented a strict non-fraternization policy between the US troops and German citizens. The State Department and individual US congressmen pressured to have this policy lifted. In June 1945 the prohibition against speaking with German children was loosened. In July troops were permitted to speak to German adults in certain circumstances. In September 1945 the entire policy was dropped. Only the ban on marriage between Americans and German or Austrian civilians remained in place until 11 December 1946 and 2 January 1946 respectively.[14]

Industrial disarmament in West Germany

The initial proposal for the post-surrender policy of the Western powers, the so-called Morgenthau Plan proposed by Henry Morgenthau Jr., was one of "pastoralization".[15] The Morgenthau Plan, though subsequently ostensibly shelved due to public opposition, influenced occupation policy; most notably through the U.S. punitive occupation directive JCS 1067[16][17] and the industrial plans for Germany.[18]

The "Level of Industry plans for Germany" were the plans to lower German industrial potential after World War II. At the Potsdam Conference, with the U.S. operating under influence of the Morgenthau plan,[18] the victorious Allies decided to abolish the German armed forces as well as all munitions factories and civilian industries that could support them. This included the destruction of all ship and aircraft manufacturing capability. Further, it was decided that civilian industries which might have a military potential, which in the modern era of "total war" included virtually all, were to be severely restricted. The restriction of the latter was set to Germany's "approved peacetime needs", which were defined to be set on the average European standard. In order to achieve this, each type of industry was subsequently reviewed to see how many factories Germany required under these minimum level of industry requirements.

The first plan, from 29 March 1946, stated that German heavy industry was to be lowered to 50% of its 1938 levels by the destruction of 1,500 listed manufacturing plants.[19] In January 1946 the Allied Control Council set the foundation of the future German economy by putting a cap on German steel production—the maximum allowed was set at about 5,800,000 tons of steel a year, equivalent to 25% of the pre-war production level.[20] The UK, in whose occupation zone most of the steel production was located, had argued for a more limited capacity reduction by placing the production ceiling at 12 million tons of steel per year, but had to submit to the will of the U.S., France and the Soviet Union (which had argued for a 3 million ton limit). Germany was to be reduced to the standard of life it had known at the height of the Great Depression (1932).[21] Car production was set to 10% of pre-war levels, etc.[22]

By 1950, after the virtual completion of the by then much watered-down plans, equipment had been removed from 706 factories in the west and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6,700,000 tons.[18]

Timber exports from the U.S. occupation zone were particularly heavy. Sources in the U.S. government stated that the purpose of this was the "ultimate destruction of the war potential of German forests".[23]

With the beginning of the Cold War, the Western policies changed as it became evident that a return to operation of the West German industry was needed not only for the restoration of the whole European economy but also for the rearmament of West Germany as an ally against the Soviet Union. On 6 September 1946 United States Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes made the famous speech Restatement of Policy on Germany, also known as the Stuttgart speech, where he amongst other things repudiated the Morgenthau plan-influenced policies and gave the West Germans hope for the future. Reports such as The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria helped to show the U.S. public how bad the situation in Germany really was.

The next improvement came in July 1947, when after lobbying by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Generals Clay and Marshall, the Truman administration decided that economic recovery in Europe could not go forward without the reconstruction of the German industrial base on which it had previously been dependent.[24] In July 1947, President Harry S. Truman rescinded on "national security grounds"[24] the punitive occupation directive JCS 1067, which had directed the U.S. forces in Germany to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany." It was replaced by JCS 1779, which instead stressed that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany."[25]

The dismantling did however continue, and in 1949 West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer wrote to the Allies requesting that it end, citing the inherent contradiction between encouraging industrial growth and removing factories and also the unpopularity of the policy.[26]: 259 Support for dismantling was by this time coming predominantly from the French, and the Petersberg Agreement of November 1949 reduced the levels vastly, though dismantling of minor factories continued until 1951. The final limitations on German industrial levels were lifted after the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, though arms manufacture remained prohibited.[26]: 260, 270–71

Relations with France

Germany's second largest center of mining and industry, Upper Silesia, had been handed over by the Allies to Poland at the Potsdam Conference and the German population was being forcibly expelled.[27] The International Authority for the Ruhr (IAR) was created as part of the agreement negotiated at the London Six-Power conference in June 1948 to establish the Federal Republic of Germany.[28] French support to internationalize the Ruhr through the IAR was abandoned in 1951 with the West German agreement to pool its coal and steel markets within European Coal and Steel Community.

In the speech Restatement of Policy on Germany, held in Stuttgart on 6 September 1946, the United States Secretary of State James F. Byrnes stated the U.S. motive in detaching the Saar from Germany as "The United States does not feel that it can deny to France, which has been invaded three times by Germany in 70 years, its claim to the Saar territory". The Saar came under French administration in 1946 as the Saar Protectorate, but did return to Germany in January 1957 (following a referendum), with economic reintegration with Germany occurring a few years later.

In August 1954 the French parliament voted down the treaty that would have established the European Defense Community, a treaty they themselves had proposed. Germany was eventually allowed to rearm under the auspices of the Western European Union, and later NATO.

Dismantling in East Germany

The Soviet Union engaged in a massive industrial dismantling campaign in its occupation zone, much more intensive than that carried out by the Western powers. While the Soviet powers soon realized that their actions alienated the German workforce from the Communist cause, they decided that the desperate economic situation within the Soviet Union took priority over alliance building. The allied leaders had agreed on paper to economic and political cooperation but the issue of reparations dealt an early blow to the prospect of a united Germany in 1945. The figure of $20 Billion had been floated by Stalin as an adequate recompense but as the United States refused to consider this a basis for negotiation The Soviet Union was left only with the opportunity of extracting its own reparations, at a heavy cost to the East Germans. This was the beginning of the formal split of Germany.[citation needed]

Marshall Plan and currency reform

With the Western Allies eventually becoming concerned about the deteriorating economic situation in their "Trizone", the American Marshall Plan of economic aid was extended to Western Germany in 1948 and a currency reform, which had been prohibited under the previous occupation directive JCS 1067, introduced the Deutsche Mark and halted rampant inflation. Though the Marshall Plan is regarded as playing a key psychological role in the West German recovery, other factors were also significant.[29]

The Soviets had not agreed to the currency reform; in March 1948 they withdrew from the four-power governing bodies, and in June 1948 they initiated the Berlin Blockade, blocking all ground transport routes between Western Germany and West Berlin. The Western Allies replied with a continuous airlift of supplies to the western half of the city. The Soviets ended the blockade after 11 months.

Reparations to the U.S.

The Allies confiscated intellectual property of great value, all German patents, both in Germany and abroad, and used them to strengthen their own industrial competitiveness by licensing them to Allied companies.[30] Beginning immediately after the German surrender and continuing for the next two years, the U.S. pursued a vigorous program to harvest all technological and scientific know-how as well as all patents in Germany. John Gimbel comes to the conclusion, in his book "Science Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Postwar Germany", that the "intellectual reparations" taken by the U.S. and the UK amounted to close to $10 billion.[31][a] During the more than two years that this policy was in place, no industrial research in Germany could take place, as any results would have been automatically available to overseas competitors who were encouraged by the occupation authorities to access all records and facilities. Meanwhile, thousands of the best German scientists were being put to work in the U.S. (see also Operation Paperclip)

Nutritional levels

During the war, Germans seized food supplies from occupied countries and forced millions of foreigners to work on German farms and factories, in addition to food shipped from farms in eastern Germany. When this ended in 1945, the German rationing system (which stayed in place) had much lower supplies of food.[32]: 342–54 The U.S. Army sent in large shipments of food to feed some 7.7 million prisoners of war—far more than they had expected[32]: 200 —as well as the general population.[33] For several years following the surrender, German nutritional levels were low. The Germans were not high on the priority list for international aid, which went to the victims of the Nazis.[34]: 281 It was directed that all relief went to non-German displaced persons, liberated Allied POWs, and concentration camp inmates.[34]: 281–82 During 1945 it was estimated that the average German civilian in the U.S. and UK occupation zones received 1200 kilocalories a day in official rations, not counting food they grew themselves or purchased on the large-scale black market.[34]: 280 In early October 1945 the UK government privately acknowledged in a cabinet meeting that German civilian adult death rates had risen to 4 times the pre-war levels and death rates amongst the German children had risen by 10 times the pre-war levels.[34]: 280 The German Red Cross was dissolved, and the International Red Cross and the few other allowed international relief agencies were kept from helping Germans through strict controls on supplies and on travel.[34]: 281–82 The few agencies permitted to help Germans, such as the indigenous Caritasverband, were not allowed to use imported supplies. When the Vatican attempted to transmit food supplies from Chile to German infants, the U.S. State Department forbade it.[34]: 281 The German food situation became worse during the very cold winter of 1946–1947 when German calorie intake ranged from 1,000–1,500 kilocalories per day, a situation made worse by severe lack of fuel for heating.[34]: 244

Forced labour reparations

As agreed by the Allies at the Yalta Conference Germans were used as forced labor as part of the reparations to be extracted. German prisoners were for example forced to clear minefields in France and the Low Countries. By December 1945 it was estimated by French authorities that 2,000 German prisoners were being killed or injured each month in accidents.[35] In Norway the last available casualty record, from 29 August 1945, shows that by that time a total of 275 German soldiers died while clearing mines, while 392 had been injured.[36]

Mass rape

Norman Naimark writes in The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949 that although the exact number of women and girls who were raped by members of the Red Army in the months preceding and years following the capitulation will never be known, their numbers are likely in the hundreds of thousands, quite possibly as high as the 2,000,000 victims estimate made by Barbara Johr, in "Befreier und Befreite". Many of these victims were raped repeatedly. Naimark states that not only had each victim to carry the trauma with her for the rest of her days, it inflicted a massive collective trauma on the East German nation (the German Democratic Republic). Naimark concludes "The social psychology of women and men in the Soviet zone of occupation was marked by the crime of rape from the first days of occupation, through the founding of the GDR in the fall of 1949, until—one could argue—the present."[37] Some of the victims had been raped as many as 60 to 70 times[dubious – discuss].[38] According to German historian Miriam Gebhardt, as many as 190,000 women were raped by U.S. soldiers in Germany.[39]

States in Germany

On 17 December 1947, the Saar Protectorate had been established under French control, in the area corresponding to the current German state of Saarland. It was not allowed to join its fellow German neighbors until a plebiscite in 1955 rejected the proposed autonomy.[40] This paved the way for the accession of the Saarland to the Federal Republic of Germany as its 12th state, which went into effect on 1 January 1957.

On 23 May 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, Bundesrepublik Deutschland) was established on the territory of the Western occupied zones, with Bonn as its "provisional" capital. It comprised the area of 11 newly formed states (replacing the pre-war states), with present-day Baden-Württemberg being split into three states until 1952). The Federal Republic was declared to have "the full authority of a sovereign state" on 5 May 1955. On 7 October 1949 the German Democratic Republic (GDR, Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR)), with East Berlin as its capital, was established in the Soviet Zone.

The 1952 Stalin Note proposed German reunification and superpower disengagement from Central Europe but Britain, France, and the United States rejected the offer as insincere. Also, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer preferred "Westintegration", rejecting "experiments".

In English, the two larger states were known informally as "West Germany" and "East Germany" respectively. In both cases, the former occupying troops remained permanently stationed there. The former German capital, Berlin, was a special case, being divided into East Berlin and West Berlin, with West Berlin completely surrounded by East German territory. Though the German inhabitants of West Berlin were citizens of the Federal Republic of Germany, West Berlin was not legally incorporated into West Germany; it remained under the formal occupation of the western allies until 1990, although most day-to-day administration was conducted by an elected West Berlin government.

West Germany was allied with the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. A western democratic country with a "social market economy", the country would from the 1950s onwards come to enjoy prolonged economic growth (Wirtschaftswunder) following the Marshall Plan help from the Allies, the currency reform of June 1948 and helped by the fact that the Korean War (1950–53) led to a worldwide increased demand for goods, where the resulting shortage helped overcome lingering resistance to the purchase of German products.

East Germany was at first occupied by and later (May 1955) allied with the Soviet Union.

West Germany (Federal Republic of Germany)

The Western Allies turned over increasing authority to West German officials and moved to establish a nucleus for a future German government by creating a central Economic Council for their zones. The program later provided for a West German constituent assembly, an occupation statute governing relations between the Allies and the German authorities, and the political and economic merger of the French with the British and American zones. On 23 May 1949, the Grundgesetz (Basic Law), the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany, was promulgated. Following elections in August, the first federal government was formed on 20 September 1949, by Konrad Adenauer (CDU). Adenauer's government was a coalition of the CDU, the CSU and the Free Democrats. The next day, the occupation statute came into force, granting powers of self-government with certain exceptions.

In 1949 the new provisional capital of the Federal Republic of Germany was established in Bonn, after Chancellor Konrad Adenauer intervened emphatically for Bonn (which was only fifteen kilometers away from his hometown). Most of the members of the German constitutional assembly (as well as the U.S. Supreme Command) had favored Frankfurt am Main where the Hessian administration had already started the construction of an assembly hall. The Parlamentarischer Rat (interim parliament) proposed a new location for the capital, as Berlin was then a special administrative region controlled directly by the allies and surrounded by the Soviet zone of occupation. The former Reichstag building in Berlin was occasionally used as a venue for sittings of the Bundestag and its committees and the Bundesversammlung, the body which elects the German Federal President. However, the Soviets disrupted the use of the Reichstag building by flying very noisy supersonic jets near the building. A number of cities were proposed to host the federal government, and Kassel (among others) was eliminated in the first round. Other politicians opposed the choice of Frankfurt out of concern that, as one of the largest German cities and a former centre of the Holy Roman Empire, it would be accepted as a "permanent" capital of Germany, thereby weakening the West German population's support for reunification and the eventual return of the Government to Berlin.

After the Petersberg agreement West Germany quickly progressed toward fuller sovereignty and association with its European neighbors and the Atlantic community. The London and Paris agreements of 1954 restored most of the state's sovereignty (with some exceptions) in May 1955 and opened the way for German membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). In April 1951, West Germany joined with France, Italy and the Benelux countries in the European Coal and Steel Community (forerunner of the European Union).[41]

The outbreak of the Korean War (June 1950) led to Washington calling for the rearmament of West Germany in order to defend western Europe from the Soviet threat. But the memory of German aggression led other European states to seek tight control over the West German military. Germany's partners in the Coal and Steel Community decided to establish a European Defence Community (EDC), with an integrated army, navy and air force, composed of the armed forces of its member states. The West German military would be subject to complete EDC control, but the other EDC member states (Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) would cooperate in the EDC while maintaining independent control of their own armed forces.

Though the EDC treaty was signed (May 1952), it never entered into force. France's Gaullists rejected it on the grounds that it threatened national sovereignty, and when the French National Assembly refused to ratify it (August 1954), the treaty died. The French had killed their own proposal. Other means had to be found to allow West German rearmament. In response, the Brussels Treaty was modified to include West Germany, and to form the Western European Union (WEU). West Germany was to be permitted to rearm, and have full sovereign control of its military; the WEU would, however, regulate the size of the armed forces permitted to each of its member states. Fears of a return to Nazism, however, soon receded, and as a consequence, these provisions of the WEU treaty have little effect today.

Between 1949 and 1960, the West German economy grew at an unparalleled rate.[42] Low rates of inflation, modest wage increases and a quickly rising export quota made it possible to restore the economy and brought a modest prosperity. According to the official statistics the German gross national product grew in average by about 7% annually between 1950 and 1960.

| 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 |

| + 10.5 | + 8.3 | + 7.5 | + 7.4 | +11.5 | + 6.9 | + 5.4 | +3.3 | + 6.7 | +8.8 |

[43]: 36

The initial demand for housing, the growing demand for machine tools, chemicals, and automobiles and a rapidly increasing agricultural production were the initial triggers to this 'Wirtschaftswunder' (economic miracle) as it was known, although there was nothing miraculous about it. The era became closely linked with the name of Ludwig Erhard, who led the Ministry of Economics during the decade. Unemployment at the start of the decade stood at 10.3%, but by 1960 it had dropped to 1.2%, practically speaking full employment. In fact, there was a growing demand for labor in many industries as the workforce grew by 3% per annum, the reserves of labor were virtually used up.[43]: 36 The millions of displaced persons and the refugees from the eastern provinces had all been integrated into the workforce. At the end of the decade, thousands of younger East Germans were packing their bags and migrating westwards, posing an ever-growing problem for the GDR nomenclature. With the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 they hoped to end the loss of labor and in doing so they posed the West German government with a new problem—how to satisfy the apparently insatiable demand for labor. The answer was to recruit unskilled workers from Southern European countries; the era of the Gastarbeiter (foreign laborers) began.

In October 1961 an initial agreement was signed with the Turkish government and the first Gastarbeiter began to arrive. By 1966, some 1,300,000 foreign workers had been recruited mainly from Italy, Turkey, Spain, and Greece. By 1971, the number had reached 2.6 million workers. The initial plan was that single workers would come to Germany, would work for a limited number of years and then return home. The significant differences between wages in their home countries and in Germany led many workers to bring their families and to settle—at least until retirement—in Germany. That the German authorities took little notice of the radical changes that these shifts of population structure meant was the cause of considerable debate in later years.[citation needed]

In the 1950s Federal Republic, restitution laws for compensation for those who had suffered under the Nazis was limited to only those who had suffered from "racial, religious or political reasons", which were defined in such a way as to sharply limit the number of people entitled to collect compensation.[44]: 564 According to the 1953 law on compensation for suffering during the National Socialist era, only those with a territorial connection with Germany could receive compensation for their suffering, which had the effect of excluding the millions of people, mostly from Central and Eastern Europe, who had been taken to Germany to work as slave labor during World War II.[44]: 565 In the same vein, to be eligible for compensation they would have to prove that they were part of the "realm of German language and culture", a requirement that excluded most of the surviving slave laborers who did not know German or at least enough German to be considered part of the "realm of German language and culture".[44]: 567 Likewise, the law excluded homosexuals, Gypsies, Communists, Asoziale ("Asocials" – people considered by the National Socialist state to be anti-social, a broad category comprising anyone from petty criminals to people who were merely eccentric and non-conformist), and homeless people for their suffering in the concentration camps under the grounds that all these people were "criminals" whom the state was protecting German society from by sending them to concentration camps, and in essence these victims of the National Socialist state got what they deserved, making them unworthy of compensation.[44]: 564, 565 In this regard it is significant[according to whom?] that the 1935 version of Paragraph 175 was not repealed until 1969.[45] As a result, German homosexuals – in many cases survivors of the concentration camps – between 1949 and 1969 continued to be convicted under the same law that had been used to convict them between 1935 and 1945, though in the period 1949–69 they were sent to prison rather than to a concentration camp.[45]

A study done in 1953 showed that of the 42,000 people who had survived the Buchenwald concentration camp, only 700 were entitled to compensation under the 1953 law.[44]: 564 The German historian Alf Lüdtke wrote that the decision to deny that the Roma and the Sinti had been victims of National Socialist racism and to exclude the Roma and Sinti from compensation under the grounds that they were all "criminals" reflected the same anti-Gypsy racism that made them the target of persecution and genocide during the National Socialist era.[44]: 565, 568–69 The cause of the Roma and Sinti excited so little public interest that it was not until 1979 that a group was founded to lobby for compensation for the Roma and the Sinti survivors.[44]: 568–569 Communist concentration camp survivors were excluded from compensation under the grounds that in 1933 the KPD had been seeking "violent domination" by working for a Communist revolution, and thus the banning of the KPD and the subsequent repression of the Communists were justified.[44]: 564 In 1956, the law was amended to allow Communist concentration camp survivors to collect compensation provided that they had not been associated with Communist causes after 1945, but as almost all the surviving Communists belonged to the Union of Persecutees of the Nazi Regime, which had been banned in 1951 by the Hamburg government as a Communist front organisation, the new law did not help many of the KPD survivors.[44]: 565–566 Compensation started to be paid to most Communist survivors regardless if they had belonged to the VVN or not following a 1967 court ruling, through the same court ruling had excluded those Communists who had "actively" fought the constitutional order after the banning of the KPD again in 1956.[44]: 565–566 Only in the 1980s were demands made mostly from members of the SPD, FDP and above all the Green parties that the Federal Republic pay compensation to the Roma, Sinti, gay, homeless and Asoziale survivors of the concentration camps.[44]: 568

In regards to the memory of the Nazi period in the 1950s Federal Republic, there was a marked tendency to argue that everyone regardless of what side they had been on in World War II were all equally victims of the war.[44]: 561 In the same way, the Nazi regime tended to be portrayed in the 1950s as a small clique of criminals entirely unrepresentative of German society who were sharply demarcated from the rest of German society or as the German historian Alf Ludtke argued in popular memory that it was a case of "us" (i.e ordinary people) ruled over by "them" (i.e. the Nazis).[44]: 561–62 Though the Nazi regime itself was rarely glorified in popular memory, in the 1950s World War II and the Wehrmacht were intensely gloried and celebrated by the public.[46]: 235 In countless memoirs, novels, histories, newspaper articles, films, magazines, and Landserheft (a type of comic book in Germany glorifying war), the Wehrmacht was celebrated as an awesome, heroic fighting force that had fought a "clean war" unlike the SS and which would have won the war as the Wehrmacht was always portrayed as superior to the Allied forces had not been for mistakes on the part of Hitler or workings of "fate".[46]: 235 The Second World War was usually portrayed in heavily romantic aura in various works that celebrated the comradeship and heroism of ordinary soldiers under danger with the war itself being shown as "a great adventure for idealists and daredevils" who for the most part had a thoroughly fun time.[46]: 235 The tendency in the 1950s to glorify war by depicting World War II as a fun-filled, grand adventure for the men who served in Hitler's war machine meant the horrors and hardship of the war were often downplayed. In his 2004 essay "Celluloid Soldiers" about post-war German films, the Israeli historian Omer Bartov wrote that German films of the 1950s always showed the average German soldier as a heroic victim: noble, tough, brave, honourable and patriotic, while fighting hard in a senseless war for a regime that he did not care for.[47] Commendations of the victims of the Nazis tended to center around honoring those involved in the July 20 putsch attempt of 1944, which meant annual ceremonies attended by all the leading politicians at the Bendlerblock and Plötzensee Prison to honor those executed for their involvement in the 20 July putsch.[44]: 554–555 By contrast, almost no ceremonies were held in the 1950s at the ruins of the concentration camps like Bergen-Belsen or Dachau, which were ignored and neglected by the Länder governments in charge of their care.[44]: 555 Not until 1966 did the Land of Lower Saxony opened Bergen-Belsen to the public by founding a small "house of documentation", and even then it was in response to criticism that the Lower Saxon government was intentionally neglecting the ruins of Bergen-Belsen.[44]: 555 Though it was usually claimed at the time that everybody in the Second World War was a victim, Ludtke commented that the disparity between the millions of Deutsche Marks spent in the 1950s in turning the Benderblock and Plötzensee prison into sites of remembrance honoring those conservatives executed after the 20 July putsch versus the neglect of the former concentration camps suggested that in both official and popular memory that some victims of the Nazis were considered more worthy of remembrance than others.[44]: 554–555 It was against this context where popular memory was focused on glorifying the heroic deeds of the Wehrmacht while treating the genocide by the National Socialist regime as almost a footnote that in the autumn of 1959 that the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno gave a much-publicized speech on TV that called for Vergangenheitsbewältigung ("coming to terms with the past").[44]: 550 Adorno stated that most people were engaged in a process of "willful forgetting" about the Nazi period and used euphemistic language to avoid confronting the period such as the use of the term Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) for the pogrom of November 1938.[44]: 550 Adorno called for promoting a critical "consciousness" that would allow people to "come to terms with the past".[44]: 551

West German authorities made great efforts to end the denazification process that had been started by the occupying powers and to liberate war criminals from prison, including those that had been convicted at the Nuremberg trials, while demarcating the sphere of legitimate political activity against blatant attempts at a political rehabilitation of the Nazi regime.[48]

Until the end of occupation in 1990, the three Western Allies retained occupation powers in Berlin and certain responsibilities for Germany as a whole. Under the new arrangements, the Allies stationed troops within West Germany for NATO defense, pursuant to stationing and status-of-forces agreements. With the exception of 45,000 French troops, Allied forces were under NATO's joint defense command. (France withdrew from the collective military command structure of NATO in 1966.)

Political life in West Germany was remarkably stable and orderly. The Adenauer era (1949–63) was followed by a brief period under Ludwig Erhard (1963–66) who, in turn, was replaced by Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1966–69). All governments between 1949 and 1966 were formed by coalitions of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union (CSU), either alone or in coalition with the smaller Free Democratic Party (FDP).

1960s: a time for reform

The grand old man of German postwar politics had to be dragged—almost literally—out of office in 1963.[tone] In 1959, it was time to elect a new president and Adenauer decided that he would place Erhard in this office. Erhard was not enthusiastic, and to everybody's surprise, Adenauer decided at the age of 83 that he would take on the position. His aim was apparently to remain in control of German politics for another ten years despite the growing mood for change, but when his advisers informed him just how limited the powers of the president were he quickly lost interest.[43]: 3 An alternative candidate was needed and eventually the Minister of Agriculture, Heinrich Lübke took on the task and was duly elected.

In October 1962, the weekly news magazine Der Spiegel published an analysis of the West German military defense. The conclusion was that there were several weaknesses in the system. Ten days after publication, the offices of Der Spiegel in Hamburg were raided by the police and quantities of documents were seized under the orders of the CSU Defense Minister Franz Josef Strauss. Chancellor Adenauer proclaimed in the Bundestag that the article was tantamount to high treason and that the authors would be prosecuted. The editor/owner of the magazine, Rudolf Augstein spent some time in jail before the public outcry over the breaking of laws on freedom of the press became too loud to be ignored. The FDP members of Adenauer's cabinet resigned from the government, demanding the resignation of Franz Josef Strauss, Defence Minister, who had decidedly overstepped his competence during the crisis by his heavy-handed attempt to silence Der Spiegel for essentially running a story that was unflattering to him (which incidentally was true).[49] The British historian Frederick Taylor argued that the Federal Republic under Adenauer retained many of the characteristics of the authoritarian "deep state" that existed under the Weimar Republic, and that the Der Spiegel affair marked an important turning point in German values as ordinary people rejected the old authoritarian values in favor of the more democratic values that are today seen as the bedrock of the Federal Republic.[49] Adenauer's own reputation was impaired by Spiegel affair and he announced that he would step down in the autumn of 1963. His successor was to be the Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard, who was the man widely credited as the father of the "economic miracle" of the 1950s and of whom great things[clarification needed] were expected.[by whom?][43]: 5

The proceedings of the War Crimes Tribunal at Nuremberg had been widely publicised in Germany but, a new generation of teachers, educated with the findings of historical studies, could begin to reveal the truth about the war and the crimes committed in the name of the German people. In 1963, a German court ruled that a KGB assassin named Bohdan Stashynsky who had committed several murders in the Federal Republic in the late 1950s was not legally guilty of murder, but was only an accomplice to murder as the responsibility for Stashynsky's murders rested only with his superiors in Moscow who had given him his orders.[46]: 245 The legal implications of the Stashynsky case, namely that in a totalitarian system only executive decision-makers can be held legally responsible for any murders committed and that anyone else who follows orders and commits murders were just accomplices to murder was to greatly hinder the prosecution of Nazi war criminals in the coming decades, and ensured that even when convicted, that Nazi criminals received the far lighter sentences reserved for accomplices to murders than the harsher sentences given to murderers.[46]: 245 The term executive decision-maker who could be found guilty of murder was reserved by the courts only for those at the highest levels of the Reich leadership during the Nazi period.[46]: 245 The only way that a Nazi criminal could be convicted of murder was to show that they were not following orders at the time and had acted on their initiative when killing someone.[50] One courageous attorney, Fritz Bauer patiently gathered evidence on the guards of the Auschwitz death camp and about twenty were put trial in Frankfurt between 1963–1965 in what came to be known as the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials. The men on trial in Frankfurt were tried only for murders and other crimes that they committed on their own initiative at Auschwitz and were not tried for anything that they did at Auschwitz when following orders, which was considered by the courts to be the lesser crime of accomplice to murder.[50] Because of this, Bauer could only indict for murder those who killed when not following orders, and those who had killed when following orders were indicted as accomplices to murder. Moreover because of the legal distinction between murderers and accomplices to murder, an SS man who killed thousands while operating the gas chambers at Auschwitz could only be found guilty of being accomplice to murder because he had been following orders, while an SS man who had beaten one inmate to death on his initiative could be convicted of murder because he had not been following orders.[50] Daily newspaper reports and visits by school classes to the proceedings revealed to the German public the nature of the concentration camp system and it became evident that the Shoah was of vastly greater dimensions than the German population had believed. (The term 'Holocaust' for the systematic mass-murder of Jews first came into use in 1943 in a New York Times piece that references "the hundreds and thousands of European Jews still surviving the Nazi holocaust". The term came into widespread use to describe the event following the TV film Holocaust in 1978) The processes set in motion by the Auschwitz trial reverberated decades later.

In the early sixties, the rate of economic growth slowed down significantly. In 1962, the growth rate was 4.7% and the following year, 2.0%. After a brief recovery, the growth rate petered into a recession, with no growth in 1967. The economic showdown forced Erhard's resignation in 1966 and he was replaced with Kurt Georg Kiesinger of the CDU. Kiesinger was to attract much controversy because in 1933 he had joined the National Socialist Legal Guild and NSDAP (membership in the former was necessary in order to practice law, but membership in the latter was entirely voluntary).

Kiesinger's 1966–69 grand coalition was between West Germany's two largest parties, the CDU/CSU and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). This was important for the introduction of new emergency acts—the grand coalition gave the ruling parties the two-thirds majority of votes required for their ratification. These controversial acts allowed basic constitutional rights such as freedom of movement to be limited in case of a state of emergency.

During the time leading up to the passing of the laws, there was fierce opposition to them, above all by the Free Democratic Party, the rising German student movement, a group calling itself Notstand der Demokratie (Democracy in Crisis), the Außerparlamentarische Opposition and members of the Campaign against Nuclear Armament. The late 1960s saw the rise of the student movement and university campuses in a constant state of uproar. A key event in the development of open democratic debate occurred in 1967 when the Shah of Iran visited West Berlin. Several thousand demonstrators gathered outside the Opera House where he was to attend a special performance. Supporters of the Shah (later known as 'Jubelperser'), armed with staves and bricks, attacked the protesters while the police stood by and watched. A demonstration in the center was being forcibly dispersed when a bystander named Benno Ohnesorg was shot in the head and killed by a plain-clothed policeman Karl-Heinz Kurras. (It has now been established that the policeman, Kurras, was a paid spy of the East German Stasi security forces.)[citation needed] Protest demonstrations continued, and calls for more active opposition by some groups of students were made, which was declared by the press, especially the tabloid Bild-Zeitung newspaper, to be acts of terrorism. The conservative Bild-Zeitung waged a massive campaign against the protesters who were declared to be just hooligans and thugs in the pay of East Germany. The press baron Axel Springer emerged as one of the principal hate figures for the student protesters because of Bild-Zeitung's often violent attacks on them. Protests against the US intervention in Vietnam, mingled with anger over the vigor with which demonstrations were repressed, led to mounting militancy among the students at the universities of Berlin. One of the most prominent campaigners was a young man from East Germany called Rudi Dutschke who also criticised the forms of capitalism that were to be seen in West Berlin. Just before Easter 1968, a young man[who?] tried to kill Dutschke as he bicycled to the student union, seriously injuring him. All over West Germany, thousands demonstrated against the Springer newspapers which were seen as the prime cause of the violence against students. Trucks carrying newspapers were set on fire and windows in office buildings broken.[51] In the wake of these demonstrations, in which the question of America's role in Vietnam began to play a bigger role, came a desire among the students to find out more about the role of their parents' generation in the Nazi era.

In 1968, the Bundestag passed a Misdemeanors Bill dealing with traffic misdemeanors, into which a high-ranking civil servant named Dr. Eduard Dreher who had been drafting the bill inserted a prefatory section to the bill under a very misleading heading that declared that henceforth there was a statute of limitations of 15 years from the time of the offense for the crime of being an accomplices to murder which was to apply retroactively, which made it impossible to prosecute war criminals even for being accomplices to murder since the statute of limitations as now defined for the last of the suspects had expired by 1960.[46]: 249 The Bundestag passed the Misdemeanors Bill without bothering to read the bill in its entirety so its members missed Dreher's amendment.[46]: 249 It was estimated in 1969 that thanks to Dreher's amendment to the Misdemeanors Bill that 90% of all Nazi war criminals now enjoyed total immunity from prosecution.[46]: 249–50 The prosecutor Adalbert Rückerl who headed the Central Bureau for the Prosecution of National Socialist Crimes told an interviewer in 1969 that this amendment had done immense harm to the ability of the Bureau to prosecute those suspected of war crimes and crimes against humanity.[46]: 249

The calling in question of the actions and policies of the government led to a new climate of debate by the late 1960s. The issues of emancipation, colonialism, environmentalism and grass roots democracy were discussed at all levels of society. In 1979, the environmental party, the Greens, reached the 5% limit required to obtain parliamentary seats in the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen provincial election. Also of great significance was the steady growth of a feminist movement in which women demonstrated for equal rights. Until 1979, a married woman had to have the permission of her husband if she wanted to take on a job or open a bank account. Parallel to this, a gay movement began to grow in the larger cities, especially in West Berlin, where homosexuality had been widely accepted during the twenties in the Weimar Republic. In 1969, the Bundestag repealed the 1935 Nazi amendment to Paragraph 175, which not only made homosexual acts a felony, but had also made any expressions of homosexuality illegal (before 1935 only gay sex had been illegal). However, Paragraph 175 which made homosexual acts illegal remained on the statute books and was not repealed until 1994, although it had been softened in 1973 by making gay sex illegal only with those under the age of 18.

Anger over the treatment of demonstrators following the death of Benno Ohnesorg and the attack on Rudi Dutschke, coupled with growing frustration over the lack of success in achieving their aims, led to growing militancy among students and their supporters. In May 1968, three young people set fire to two department stores in Frankfurt; they were brought to trial and made very clear to the court that they regarded their action as a legitimate act in what they described as the 'struggle against imperialism'.[51] The student movement began to split into different factions, ranging from the unattached liberals to the Maoists and supporters of direct action in every form—the anarchists. Several groups set as their objective the aim of radicalizing the industrial workers and, taking an example from activities in Italy of the Brigade Rosse, many students went to work in the factories, but with little or no success. The most notorious of the underground groups was the 'Baader-Meinhof Group', later known as the Red Army Faction, which began by making bank raids to finance their activities and eventually went underground having killed a number of policemen, several bystanders and eventually two prominent West Germans, whom they had taken captive in order to force the release of prisoners sympathetic to their ideas. The "Baader-Meinhof gang" was committed to the overthrow of the Federal Republic via terrorism in order to achieve the establishment of a Communist state. In the 1990s attacks were still being committed under the name "RAF". The last action took place in 1993 and the group announced it was giving up its activities in 1998. Evidence that the groups had been infiltrated by German Intelligence undercover agents has since emerged, partly through the insistence of the son of one of their prominent victims, the State Counsel Buback.[52]

Political developments 1969–1990

The principle is written in our Constitution – that no one has the right to give up a policy whose goal is the eventual reunification of Germany. But in a realistic view of the world, this is a goal that could take generations beyond my own to achieve.

In the 1969 election, the SPD—headed by Willy Brandt—gained enough votes to form a coalition government with the FDP. Although chancellor for only just over four years, Brandt was one of the most popular politicians in the whole period. Brandt was a gifted speaker and the growth of the Social Democrats from there on was in no small part due to his personality.[citation needed] Brandt began a policy of rapprochement with West Germany's eastern neighbors known as Ostpolitik, a policy opposed by the CDU. The issue of improving relations with Poland, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany made for an increasingly aggressive tone in public debates but it was a huge step forward when Willy Brandt and the Foreign Minister, Walther Scheel (FDP) negotiated agreements with all three countries (Moscow Agreement, August 1970, Warsaw Agreement, December 1970, Four-Power Agreement over the status of West Berlin in 1971 and an agreement on relations between West and East Germany, signed in December 1972).[43]: 32 These agreements were the basis for a rapid improvement in the relations between east and west and led, in the long term, to the dismantlement of the Warsaw Treaty and the Soviet Union's control over East-Central Europe. During a visit to Warsaw on 7 December 1970, Brandt made the Warschauer Kniefall by kneeling before a monument to those killed in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, a gesture of humility and penance that no German chancellor had made until that time. Chancellor Brandt was forced to resign in May 1974, after Günter Guillaume, a senior member of his staff, was uncovered as a spy for the East German intelligence service, the Stasi. Brandt's contributions to world peace led to his winning the Nobel Peace Prize for 1971.

Finance Minister Helmut Schmidt (SPD) formed a coalition and he served as Chancellor from 1974 to 1982. Hans-Dietrich Genscher, a leading FDP official, became Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister. Schmidt, a strong supporter of the European Community (EC) and the Atlantic alliance, emphasized his commitment to "the political unification of Europe in partnership with the USA".[54] Throughout the 1970s, the Red Army Faction had continued its terrorist campaign, assassinating or kidnapping politicians, judges, businessmen, and policemen. The highpoint of the RAF violence came with the German Autumn in autumn 1977. The industrialist Hanns-Martin Schleyer was kidnapped on 5 September 1977 in order to force the government to free the imprisoned leaders of the Baader-Meinhof Gang. A group from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine hijacked Lufthansa Flight 181 to seize further hostages to free the RAF leaders. On 18 October 1977, the Lufthansa jet was stormed in Mogadishu by the GSG 9 commando unit, who were able to free the hostages. The same day, the leaders of the Baader-Meinhof gang, who had been waging a hunger strike, were found dead in their prison cells with gunshot wounds, which led to Schleyer being executed by his captors. The deaths were controversially ruled suicides.[55] The Red Army Faction was to continue its terrorist campaign into the 1990s, but the German Autumn of 1977 was the highpoint of its campaign. That the Federal Republic had faced a crisis caused by a terrorist campaign from the radical left without succumbing to dictatorship as many feared that it would, was seen as vindication of the strength of German democracy.[citation needed]

In January 1979, the American mini-series Holocaust aired in West Germany.[44]: 543 The series, which was watched by 20 million people or 50% of West Germans, first brought the matter of the genocide in World War II to widespread public attention in a way that it had never been before.[44]: 545–6 After each part of Holocaust was aired, there was a companion show where a panel of historians could answer questions from people phoning in.[44]: 544–6 The historians' panels were literally overwhelmed with thousands of phone calls from shocked and outraged Germans, a great many of whom stated that they were born after 1945 and that was the first time that they learned that their country had practiced genocide in World War II.[44]: 545–6 By the late 1970s, an initially small number of young people had started to demand that the Länder governments stop neglecting the sites of the concentration camps, and start turning them into proper museums and sites of remembrance, turning them into "locations of learning" meant to jar visitors into thinking critically about the Nazi period.[44]: 556–7

In 1980, the CDU/CSU ran Strauss as their joint candidate in the elections, and he was crushingly[clarification needed] defeated by Schmidt. In October 1982, the SPD-FDP coalition fell apart when the FDP joined forces with the CDU/CSU to elect CDU chairman Helmut Kohl as Chancellor in a Constructive Vote of No Confidence. Genscher continued as Foreign Minister in the new Kohl government. Following national elections in March 1983, Kohl emerged in firm control of both the government and the CDU. The CDU/CSU fell just short of an absolute majority, due to the entry into the Bundestag of the Greens, who received 5.6% of the vote. In 1983, despite major protests from peace groups, the Kohl government allowed Pershing II missiles to be stationed in the Federal Republic to counter the deployment of the SS-20 cruise missiles by the Soviet Union in East Germany. In 1985, Kohl, who had something of a tin ear when it came to dealing with the Nazi past,[clarification needed] caused much controversy when he invited President Ronald Reagan of the United States to visit the war cemetery at Bitburg to mark the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II. The Bitburg cemetery was soon revealed to contain the graves of SS men, which Kohl stated that he did not see as a problem and that to refuse to honor all of the dead of Bitburg including the SS men buried there was an insult to all Germans. Kohl stated that Reagan could come to the Federal Republic to hold a ceremony to honor the dead of Bitburg or not come at all, and that to change the venue of the service to another war cemetery that did not have SS men buried in it was not acceptable to him. Even more controversy was caused by Reagan's statement that all of the SS men killed fighting for Hitler in World War II were "just kids" who were just as much the victims of Hitler as those who been murdered by the SS in the Holocaust.[56] Despite the huge controversy caused by honoring the SS men buried at Bitburg, the visit to Bitburg went ahead, and Kohl and Reagan honored the dead of Bitburg. What was intended to promote German-American reconciliation turned out to be a public relations disaster that had the opposite effect. Public opinion polls showed that 72% of West Germans supported the service at Bitburg while American public opinion overwhelming disapproved of Reagan honoring the memory of the SS men who gave their lives for Hitler.[citation needed]

Despite or perhaps because of the Bitburg controversy, in 1985 a campaign had been started to build a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust in Berlin.[44]: 557 It was felt by at least some Germans that there was something wrong about the Chancellor and the President of the United States honoring the memory of the SS men buried at Bitburg while there was no memorial to any of the people murdered in the Holocaust. The campaign to build a Holocaust memorial, which Germany until then lacked, was given a major boost in November 1989 by the call by television journalist Lea Rosh to build the memorial at the site for the former Gestapo headquarters.[44]: 557 In April 1992, the City of Berlin finally decided that a Holocaust memorial could be built.[44]: 557 Along the same lines, in August 1987, protests put a stop to plans by the City of Frankfurt to raze the last remains of the Frankfurt Jewish Ghetto in order to redevelop the land, arguing that the remnants of the Frankfurt ghetto needed to be preserved.[44]: 557

In January 1987, the Kohl-Genscher government was returned to office, but the FDP and the Greens gained at the expense of the larger parties. Kohl's CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU, slipped from 48.8% of the vote in 1983 to 44.3%. The SPD fell to 37%; long-time SPD chairman Brandt subsequently resigned in April 1987 and was succeeded by Hans-Jochen Vogel. The FDP's share rose from 7% to 9.1%, its best showing since 1980. The Greens' share rose to 8.3% from their 1983 share of 5.6%. Later in 1987, Kohl had a summit with the East German leader Erich Honecker. Unknown to Kohl, the meeting room had been bugged by the Stasi, and the Stasi tapes of the summit had Kohl saying to Honecker that he did not see any realistic chance of reunification in the foreseeable future.

East Germany (German Democratic Republic)

In the Soviet occupation zone, the Social Democratic Party was forced to merge with the Communist Party in April 1946 to form a new party, the Socialist Unity Party (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands or SED). The October 1946 elections resulted in coalition governments in the five Land (state) parliaments with the SED as the undisputed leader.

A series of people's congresses were called in 1948 and early 1949 by the SED. Under Soviet direction, a constitution was drafted on 30 May 1949, and adopted on 7 October, the day when East Germany was formally proclaimed. The People's Chamber (Volkskammer)—the lower house of the East German parliament—and an upper house—the States Chamber (Länderkammer)—were created. (The Länderkammer was abolished again in 1958.) On 11 October 1949, the two houses elected Wilhelm Pieck as President, and an SED government was set up. The Soviet Union and its East European allies immediately recognized East Germany, although it remained largely unrecognized by noncommunist countries until 1972–73. East Germany established the structures of a single-party, centralized, totalitarian communist state. On 23 July 1952, the traditional Länder were abolished and, in their place, 14 Bezirke (districts) were established. Even though other parties formally existed, effectively, all government control was in the hands of the SED, and almost all important government positions were held by SED members.

The National Front was an umbrella organization nominally consisting of the SED, four other political parties controlled and directed by the SED, and the four principal mass organizations—youth, trade unions, women, and culture. However, control was clearly and solely in the hands of the SED. Balloting in East German elections was not secret. As in other Soviet bloc countries, electoral participation was consistently high, as the following results indicate. In October 1950, a year after the formation of the GDR, 98.53% of the electorate voted. 99.72% of the votes were valid and 99.72% were cast in favor of the 'National Front'—the title of the 'coalition' of the Unity Party plus their associates in other conformist groups. In election after election, the votes cast for the Socialist Unity Party were always over 99%, and in 1963, two years after the Berlin Wall was constructed, the support for the S.E.D. was 99.95%. Only 0.05% of the electorate opposed the party according to these results, the veracity of which is disputable.[57]

Industry and agriculture in East Germany

With the formation of a separate East German communist state in October 1949, the Socialist Unity Party faced a huge range of problems. Not only were the cities in ruins, much of the productive machinery and equipment had been seized by the Soviet occupation force and transported to The Soviet Union in order to make some kind of reconstruction possible. While West Germany received loans and other financial assistance from the United States, the GDR was in the role of an exporter of goods to the USSR—a role that its people could ill afford but which they could not avoid.

The S.E.D.'s intention was to transform the GDR into a socialist and later into a communist state. These processes would occur step by step according to the laws of scientific 'Marxism-Leninism' and economic planning was the key to this process. In July 1952, at a conference of the S.E.D., Walter Ulbricht announced that "the democratic (sic) and economic development, and the consciousness (Bewusstsein) of the working class and the majority of the employed classes must be developed so that the construction of Socialism becomes their most important objective."[58]: 453 This meant that the administration, the armed forces, the planning of industry and agriculture would be under the sole authority of the S.E.D. and its planning committee. Industries would be nationalized and collectivization introduced in the farm industry. When the first Five-Year Plan was announced, the flow of refugees out of East Germany began to grow. As a consequence, production fell, food became short and protests occurred in a number of factories. On 14 May 1952, the S.E.D. ordered that the production quotas (the output per man per shift) were to be increased by 10%, but wages to be kept at the former level. This decision was not popular with the new leaders in the Kremlin. Stalin had died in March 1953 and the new leadership was still evolving. The imposition of new production quotas contradicted the new direction of Soviet policies for their satellites.[58]: 454

On 5 June 1953, the S.E.D. announced a 'new course' in which farmers, craftsmen, and factory owners would benefit from a relaxation of controls. The new production quotas remained; the East German workers protested and up to sixty strikes occurred the following day. One of the window-dressing projects in the ruins of East Berlin was the construction of Stalin Allee, on which the most 'class-conscious' workers (in S.E.D. propaganda terms) were involved. At a meeting, strikers declared "You give the capitalists (the factory owners) presents, and we are exploited!"[58]: 455 A delegation of building workers marched to the headquarters of the S.E.D. demanding that the production quotas be rescinded. The crowd grew, demands were made for the removal of Ulbricht from office and a general strike called for the following day.

On 17 June 1953 strikes and demonstrations occurred in 250 towns and cities in the GDR. Between 300,000 and 400,000 workers took part in the strikes, which were specifically directed towards the rescinding of the production quotas and were not an attempt to overthrow the government. The strikers were for the most part convinced that the transformation of the GDR into a socialist state was the proper course to take but that the S.E.D. had taken a wrong turn.[58]: 457 The S.E.D. responded with all of the force at its command and also with the help of the Soviet Occupation force. Thousands were arrested, sentenced to jail and many hundreds were forced to leave for West Germany. The S.E.D. later moderated its course but the damage had been done. The real face of the East German regime was revealed. The S.E.D. claimed that the strikes had been instigated by West German agents, but there is no evidence for this. Over 250 strikers were killed, around 100 policemen and some 18 Soviet soldiers died in the uprising;[58]: 459 17 June was declared a national day of remembrance in West Germany.

Berlin

Shortly after World War II, Berlin became the seat of the Allied Control Council (ACC) i.e. the "Four Powers", which was to have governed Germany as a whole until the conclusion of a peace settlement. In 1948, however, the Soviet Union refused to participate any longer in the quadripartite administration of Germany. They also refused to continue the joint administration of Berlin and drove the government elected by the people of Berlin out of its seat in the Soviet sector and installed a communist regime in East Berlin. From then until unification, the Western Allies continued to exercise supreme authority—effective only in their sectors—through the Allied Kommandatura. To the degree compatible with the city's special status, however, they turned over control and management of city affairs to the West Berlin Senate and the House of Representatives, governing bodies established by constitutional process and chosen by free elections. The Allies and German authorities in West Germany and West Berlin never recognized the communist city regime in East Berlin or East German authority there.

During the years of West Berlin's isolation—176 kilometers (110 mi.) inside East Germany—the Western Allies encouraged a close relationship between the Government of West Berlin and that of West Germany. Representatives of the city participated as non-voting members in the West German Parliament; appropriate West German agencies, such as the supreme administrative court, had their permanent seats in the city; and the governing mayor of West Berlin took his turn as President of the Bundesrat. In addition, the Allies carefully consulted with the West German and West Berlin Governments on foreign policy questions involving unification and the status of Berlin.

Between 1948 and 1990, major events such as fairs and festivals were sponsored in West Berlin, and investment in commerce and industry was encouraged by special concessionary tax legislation. The results of such efforts, combined with effective city administration and the West Berliners' energy and spirit, were encouraging. West Berlin's morale was sustained, and its industrial production considerably surpassed the pre-war level.

The Final Settlement Treaty ended Berlin's special status as a separate area under Four Power control. Under the terms of the treaty between West and East Germany, Berlin became the capital of a unified Germany. The Bundestag voted in June 1991 to make Berlin the seat of government. The Government of Germany asked the Allies to maintain a military presence in Berlin until the complete withdrawal of the Western Group of Forces (ex-Soviet) from the territory of the former East Germany. The Russian withdrawal was completed 31 August 1994. Ceremonies were held on 8 September 1994, to mark the final departure of Western Allied troops from Berlin.

Government offices have been moving progressively to Berlin, and it became the formal seat of the federal government in 1999. Berlin also is one of the Federal Republic's 16 Länder.

Relations between East Germany and West Germany

Under Chancellor Adenauer, West Germany declared its right to speak for the entire German nation with an exclusive mandate.[59]: 18 The Hallstein Doctrine involved non-recognition of East Germany and restricted (or often ceased) diplomatic relations with countries that gave East Germany the status of a sovereign state.[60]

The constant stream of East Germans fleeing across the Inner German border to West Germany placed great strains on East German-West German relations in the 1950s. East Germany sealed the borders to West Germany in 1952, but people continued to flee from East Berlin to West Berlin. On 13 August 1961, East Germany began building the Berlin Wall around West Berlin to slow the flood of refugees to a trickle, effectively cutting the city in half and making West Berlin an enclave of the Western world in communist territory. The Wall became the symbol of the Cold War and the division of Europe. Shortly afterward, the main border between the two German states was fortified.

In 1969, Chancellor Willy Brandt announced that West Germany would remain firmly rooted in the Atlantic alliance, but would intensify efforts to improve relations with the Eastern Bloc, especially East Germany. West Germany commenced this Ostpolitik, initially under fierce opposition from the conservatives, by negotiating nonaggression treaties with the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Hungary.