History of County Durham

The history of County Durham.

Roman and pre-Roman

Remains of Prehistoric Durham[1] include a number of Neolithic earthworks.[2]

The Crawley Edge Cairns and Heathery Burn Cave are Bronze Age sites. Maiden Castle, Durham is an Iron Age site.

Brigantia, the land of the Brigantes, is said to have included what is now County Durham.[3]

There are archaeological remains of Roman Durham.[4] Dere Street and Cade's Road run through what is now County Durham. There were Roman forts at Concangis (Chester-le-Street), Lavatrae (Bowes), Longovicium (Lanchester), Piercebridge (Morbium), Vindomora (Ebchester) and Vinovium (Binchester). (The Roman fort at Arbeia (South Shields) is within the former boundaries of County Durham.) A Romanised farmstead has been excavated at Old Durham.

Anglo-Saxon

Remains of the Anglo-Saxon period[5] include a number of sculpted stones and sundials,[6] the Legs Cross, the Rey Cross and St Cuthbert's coffin.

Anglian Kingdom of Bernicia

Around AD 547, an Angle named Ida founded the kingdom of Bernicia after spotting the defensive potential of a large rock at Bamburgh, upon which many a fortification was thenceforth built.[7] Ida was able to forge, hold and consolidate the kingdom; although the native British tried to take back their land, the Angles triumphed and the kingdom endured.

Kingdom of Northumbria

In AD 604, Ida's grandson Æthelfrith forcibly merged Bernicia (ruled from Bamburgh) and Deira (ruled from York, which was known as Eforwic at the time) to create the Kingdom of Northumbria. In time, the realm was expanded, primarily through warfare and conquest; at its height, the kingdom stretched from the River Humber (from which the kingdom drew its name) to the Forth. Eventually, factional fighting and the rejuvenated strength of neighbouring kingdoms, most notably Mercia, led to Northumbria's decline.[7] The arrival of the Vikings hastened this decline, and the Scandinavian raiders eventually claimed the Deiran part of the kingdom in AD 867 (which became Jórvík). The land that would become County Durham now sat on the border with the Great Heathen Army, a border which today still (albeit with some adjustments over the years) forms the boundaries between Yorkshire and County Durham.

Despite their success south of the river Tees, the Vikings never fully conquered the Bernician part of Northumbria, despite the many raids they had carried out on the kingdom.[7] However, Viking control over the Danelaw, the central belt of Anglo-Saxon territory, resulted in Northumbria becoming isolated from the rest of Anglo-Saxon Britain. Scots invasions in the north pushed the kingdom's northern boundary back to the River Tweed, and the kingdom found itself reduced to a dependent earldom, its boundaries very close to those of modern-day Northumberland and County Durham. The kingdom was annexed into England in AD 954.[citation needed]

City of Durham founded

In AD 995, St Cuthbert's community, who had been transporting Cuthbert's remains around, partly in an attempt to avoid them falling into the hands of Viking raiders, settled at Dunholm (Durham) on a site that was defensively favourable due to the horseshoe-like path of the River Wear.[8] St Cuthbert's remains were placed in a shrine in the White Church, which was originally a wooden structure but was eventually fortified into a stone building.

Once the City of Durham had been founded, the Bishops of Durham gradually acquired the lands that would become County Durham. Bishop Aldhun began this process by procuring land in the Tees and Wear valleys, including Norton, Stockton, Escomb and Aucklandshire in 1018. In 1031, King Canute gave Staindrop to the Bishops. This territory continued to expand, and was eventually given the status of a liberty. Under the control of the Bishops of Durham, the land had various names: the "Liberty of Durham", "Liberty of St Cuthbert's Land" "the lands of St Cuthbert between Tyne and Tees" or "the Liberty of Haliwerfolc" (holy Wear folk).[9]

The bishops' special jurisdiction rested on claims that King Ecgfrith of Northumbria had granted a substantial territory to St Cuthbert on his election to the see of Lindisfarne in 684. In about 883 a cathedral housing the saint's remains was established at Chester-le-Street and Guthfrith, King of York granted the community of St Cuthbert the area between the Tyne and the Wear, before the community reached its final destination in 995, in Durham.

Following the Norman invasion, the administrative machinery of government extended only slowly into northern England. Northumberland's first recorded Sheriff was Gilebert from 1076 until 1080 and a 12th-century record records Durham regarded as within the shire.[10] However the bishops disputed the authority of the sheriff of Northumberland and his officials, despite the second sheriff for example being the reputed slayer of Malcolm Canmore, King of Scots. The crown regarded Durham as falling within Northumberland until the late thirteenth century.

Norman and Anglo-Norman

Following the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror appointed Copsig as Earl of Northumbria, thereby bringing what would become County Durham under Copsig's control. Copsig was, just a few weeks later, killed in Newburn.[11] Having already being previously offended by the appointment of a non-Northumbrian as Bishop of Durham in 1042, the people of the region became increasingly rebellious.[11] In response, in January 1069, William despatched a large Norman army, under the command of Robert de Comines, to Durham City. The army, believed to consist of 700 cavalry (about one-third of the number of Norman knights who had participated in the Battle of Hastings),[11] entered the city, whereupon they were attacked, and defeated, by a Northumbrian assault force. The Northumbrians wiped out the entire Norman army, including Comines,[11] all except for one survivor, who was allowed to take the news of this defeat back.

Following the Norman slaughter at the hands of the Northumbrians, resistance to Norman rule spread throughout Northern England, including a similar uprising in York.[11] William The Conqueror subsequently (and successfully) attempted to halt the northern rebellions by unleashing the notorious Harrying of the North (1069–1070).[12] Because William's main focus during the harrying was on Yorkshire,[11] County Durham was largely spared the Harrying.[13]

Anglo-Norman Durham refers to the Anglo-Norman period,[14] during which Durham Cathedral was built.[15]

County Palatine of Durham

Matters regarding the bishopric of Durham came to a head in 1293 when the bishop and his steward failed to attend proceedings of quo warranto held by the justices of Northumberland. The bishop's case went before parliament, where he stated that Durham lay outside the bounds of any English shire and that "from time immemorial it had been widely known that the sheriff of Northumberland was not sheriff of Durham nor entered within that liberty as sheriff. . . nor made there proclamations or attachments".[16] The arguments appear to have prevailed, as by the fourteenth century Durham was accepted as a liberty which received royal mandates direct. In effect it was a private shire, with the bishop appointing his own sheriff.[9] The area eventually became known as the "County Palatine of Durham".

Sadberge was a liberty, sometimes referred to as a county, within Northumberland. In 1189 it was purchased for the see but continued with a separate sheriff, coroner and court of pleas. In the 14th century Sadberge was included in Stockton ward and was itself divided into two wards. The division into the four wards of Chester-le-Street, Darlington, Easington and Stockton existed in the 13th century, each ward having its own coroner and a three-weekly court corresponding to the hundred court. The diocese was divided into the archdeaconries of Durham and Northumberland. The former is mentioned in 1072, and in 1291 included the deaneries of Chester-le-Street, Auckland, Lanchester and Darlington.[17]

The term palatinus is applied to the bishop in 1293, and from the 13th century onwards the bishops frequently claimed the same rights in their lands as the king enjoyed in his kingdom.[17]

Early administration

Boundaries, exclaves and population

The historic boundaries of County Durham included a main body covering the catchment of the Pennines in the west, the River Tees in the south, the North Sea in the east and the Rivers Tyne and Derwent in the north.[18][19] The county palatinate also had a number of liberties: the Bedlingtonshire, Islandshire[20] and Norhamshire[21] exclaves within Northumberland, and the Craikshire exclave within the North Riding of Yorkshire. In 1831 the county covered an area of 679,530 acres (2,750.0 km2)[22] and had a population of 253,910.[23] These exclaves were included as part of the county for parliamentary electoral purposes until 1832, and for judicial and local-government purposes until the coming into force of the Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844, which merged most remaining exclaves with their surrounding county. The boundaries of the county proper remained in use for administrative and ceremonial purposes until the Local Government Act 1972.

Survey

Boldon Book (1183 or 1184)[24] is a polyptichum for the Bishopric of Durham.[25]

Palatinate

Until the 15th century, the most important administrative officer in the Palatinate was the steward. Other officers included the sheriff, the coroners, the Chamberlain and the chancellor. The palatine exchequer originated in the 12th century. The palatine assembly represented the whole county, and dealt chiefly with fiscal questions. The bishop's council, consisting of the clergy, the sheriff and the barons, regulated judicial affairs, and later produced the Chancery and the courts of Admiralty and Marshalsea.[17]

The prior of Durham ranked first among the bishop's barons. He had his own court, and almost exclusive jurisdiction over his men.[17] A UNESCO site describes the role of the Prince-Bishops in Durham, the "buffer state between England and Scotland":[26]

From 1075, the Bishop of Durham became a Prince-Bishop, with the right to raise an army, mint his own coins, and levy taxes. As long as he remained loyal to the king of England, he could govern as a virtually autonomous ruler, reaping the revenue from his territory, but also remaining mindful of his role of protecting England’s northern frontier.

A report states that the Bishops also had the authority to appoint judges and barons and to offer pardons.[27]

There were ten palatinate barons in the 12th century, most importantly the Hyltons of Hylton Castle, the Bulmers of Brancepeth, the Conyers of Sockburne, the Hansards of Evenwood, and the Lumleys of Lumley Castle. The Nevilles owned large estates in the county. John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville de Raby rebuilt Raby Castle, their principal seat, in 1377.[17]

Edward I's quo warranto proceedings of 1293 showed twelve lords enjoying more or less extensive franchises under the bishop. The repeated efforts of the Crown to check the powers of the palatinate bishops culminated in 1536 in the Act of Resumption, which deprived the bishop of the power to pardon offences against the law or to appoint judicial officers. Moreover, indictments and legal processes were in future to run in the name of the king, and offences to be described as against the peace of the king, rather than that of the bishop. In 1596 restrictions were imposed on the powers of the chancery, and in 1646 the palatinate was formally abolished. It was revived, however, after the Restoration, and continued with much the same power until 5 July 1836, when the Durham (County Palatine) Act 1836 provided that the palatine jurisdiction should in future be vested in the Crown.[17][28][29]

Wars

During the 15th-century Wars of the Roses, Henry VI passed through Durham. On the outbreak of the Great Rebellion in 1642 Durham inclined to support the cause of Parliament, and in 1640 the high sheriff of the palatinate guaranteed to supply the Scottish army with provisions during their stay in the county. In 1642 the Earl of Newcastle formed the western counties into an association for the King's service, but in 1644 the palatinate was again overrun by a Scottish army, and after the Battle of Marston Moor (2 July 1644) fell entirely into the hands of Parliament.[17]

Parliamentary representation and secular powers

In 1614, a Bill was introduced in Parliament for securing representation to the county and city of Durham and the borough of Barnard Castle. The bishop strongly opposed the proposal as an infringement of his palatinate rights, and the county was first summoned to return members to Parliament in 1654. After the Restoration of 1660 the county and city returned two members each. In the wake of the Reform Act of 1832 the county returned two members for two divisions, and the boroughs of Gateshead, South Shields and Sunderland acquired representation.[17] The bishops lost their secular powers in 1836.[30] The boroughs of Darlington, Stockton and Hartlepool returned one member each from 1868 until the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885.[17]

Later government

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 reformed the municipal boroughs of Durham, Stockton on Tees and Sunderland. In 1875, Jarrow was incorporated as a municipal borough,[31] as was West Hartlepool in 1887.[32] At a county level, the Local Government Act 1888 reorganised local government throughout England and Wales.[33] Most of the county came under control of the newly formed Durham County Council in an area known as an administrative county. Not included were the county boroughs of Gateshead, South Shields and Sunderland. However, for purposes other than local government, the administrative county of Durham and the county boroughs continued to form a single county to which the Crown appointed a Lord Lieutenant of Durham.

Over its existence, the administrative county lost territory, both to the existing county boroughs, and because two municipal boroughs became county boroughs: West Hartlepool in 1902[32] and Darlington in 1915.[34] The county boundary with the North Riding of Yorkshire was adjusted in 1967: that part of the town of Barnard Castle historically in Yorkshire was added to County Durham,[35] while the administrative county ceded the portion of the Borough of Stockton-on-Tees in Durham to the North Riding.[36] In 1968, following the recommendation of the Local Government Commission, Billingham was transferred to the County Borough of Teesside, in the North Riding.[37] In 1971, the population of the county—including all associated county boroughs (an area of 2,570 km2 (990 sq mi)[23])—was 1,409,633, with a population outside the county boroughs of 814,396.[38]

In 1974, the Local Government Act 1972 abolished the administrative county and the county boroughs, reconstituting County Durham as a non-metropolitan county.[33][39] The reconstituted County Durham lost territory[40] to the north-east (around Gateshead, South Shields and Sunderland) to Tyne and Wear[41][42] and to the south-east (around Hartlepool) to Cleveland.[41][42] At the same time it gained the former area of Startforth Rural District from the North Riding of Yorkshire.[43] The area of the Lord Lieutenancy of Durham was also adjusted by the Act to coincide with the non-metropolitan county[44] (which occupied 3,019 km2 (1,166 sq mi) in 1981).[23]

In 1996, as part of 1990s UK local government reform by Lieutenancies Act 1997, Cleveland was abolished. Its districts were reconstituted as unitary authorities. Hartlepool and Stockton-on-Tees (north Tees) were returned to the county for the purposes of Lord Lieutenancy.[45] Darlington also became a third unitary authority of the county. The Royal Mail abandoned the use of postal counties altogether, permitted but not mandatory being at a writer wishes.[46][47][48]

As part of the 2009 structural changes to local government in England initiated by the Department for Communities and Local Government, the seven district councils within the County Council area were abolished. The County Council assumed their functions and became the fourth unitary authority. Changes came into effect on 1 April 2009.[49][50]

On 15 April 2014, North East Combined Authority was established under the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 with powers over economic development and regeneration.[51] In November 2018, Newcastle City Council, North Tyneside Borough Council, and Northumberland County Council left the authority. These later formed the North of Tyne Combined Authority.[52]

In May 2021, four parish councils of the villages of Elwick, Hart, Dalton Piercy and Greatham all issued individual votes of no confidence in Hartlepool Borough Council, and expressed their desire to join the County Durham district.[53]

In October 2021, County Durham was shortlisted for the UK City of Culture 2025. In May 2022, it lost to Bradford.[54]

Eighteenth century

Eighteenth century Durham[55] saw the appearance of dissent in the county[56] and the Durham Ox.[57] The county did not assist the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715.[58] The Statue of Neptune in the City of Durham was erected in 1729.[59]

Nineteenth century

A number of disasters happened in Nineteenth century Durham.[60] The Felling mine disasters happened in 1812, 1813, 1821 and 1847. The Philadelphia train accident happened in 1815. In 1854, there was a great fire in Gateshead. One of the West Stanley Pit disasters happened in 1882. The Victoria Hall disaster happened in 1883.

Twentieth century

One of the West Stanley Pit disasters happened in 1909. The Darlington rail crash happened in 1928. The Battle of Stockton happened in 1933. The Browney rail crash happened in 1946.

Political history

The First Treaty of Durham was made at Durham in 1136. The Second Treaty of Durham was made at Durham in 1139.[61]

Military and naval history

The county regiment was the Durham Light Infantry, which replaced, in particular, the 68th (Durham) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry) and the Militia and Volunteers of County Durham.

RAF Greatham, RAF Middleton St George and RAF Usworth were located in County Durham.

David I, the King of Scotland, invaded the county in 1136, and ravaged much of the county 1138.[62] In 17 October 1346, the Battle of Neville's Cross was fought at Neville's Cross, near the city of Durham. On 16 December 1914, during the First World War, there was a raid on Hartlepool by the Imperial German Navy.

Ecclesiastical history

Chroniclers connected with Durham include the Bede, Symeon of Durham, Geoffrey of Coldingham and Robert de Graystanes.[63]

Economic history

Legend

County Durham has long been associated with coal mining, from medieval times up to the late 20th century.[65] The Durham Coalfield covered a large area of the county, from Bishop Auckland, to Consett, to the River Tyne and below the North Sea, thereby providing a significant expanse of territory from which this rich mineral resource could be extracted.

King Stephen possessed a mine in Durham, which he granted to Bishop Pudsey, and in the same century colliers are mentioned at Coundon, Bishopwearmouth and Sedgefield. Cockfield Fell was one of the earliest Landsale collieries in Durham. Edward III issued an order allowing coal dug at Newcastle to be taken across the Tyne, and Richard II granted to the inhabitants of Durham licence to export the produce of the mines, without paying dues to the corporation of Newcastle.[17] The majority was transported from the Port of Sunderland complex, which was constructed in the 1850s.[citation needed]

Among other early industries, lead-mining was carried on in the western part of the county, and mustard was extensively cultivated. Gateshead had a considerable tanning trade and shipbuilding was undertaken at Jarrow,[17] and at Sunderland, which became the largest shipbuilding town in the world – constructing a third of Britain's tonnage.[citation needed]

The county's modern-era economic history was facilitated significantly by the growth of the mining industry during the nineteenth century. At the industry's height, in the early 20th century, over 170,000 coal miners were employed,[65] and they mined 58,700,000 tons of coal in 1913 alone.[66] As a result, a large number of colliery villages were built throughout the county as the Industrial Revolution gathered pace.

The railway industry was also a major employer during the industrial revolution, with railways being built throughout the county, such as The Tanfield Railway, The Clarence Railway and The Stockton and Darlington Railway.[67] The growth of this industry occurred alongside the coal industry, as the railways provided a fast, efficient means to move coal from the mines to the ports and provided the fuel for the locomotives. The great railway pioneers Timothy Hackworth, Edward Pease, George Stephenson and Robert Stephenson were all actively involved with developing the railways in tandem with County Durham's coal mining industry.[68] Shildon and Darlington became thriving 'railway towns' and experienced significant growths in population and prosperity; before the railways, just over 100 people lived in Shildon but, by the 1890s, the town was home to around 8,000 people, with Shildon Shops employing almost 3000 people at its height.[69]

However, by the 1930s, the coal mining industry began to diminish and, by the mid-twentieth century, the pits were closing at an increasing rate.[70] In 1951, the Durham County Development Plan highlighted a number of colliery villages, such as Blackhouse, as 'Category D' settlements, in which future development would be prohibited, property would be acquired and demolished, and the population moved to new housing, such as that being built in Newton Aycliffe.[71] Likewise, the railway industry also began to decline, and was significantly brought to a fraction of its former self by the Beeching cuts in the 1960s. Darlington Works closed in 1966 and Shildon Shops followed suit in 1984. The county's last deep mines, at Easington, Vane Tempest, Wearmouth and Westoe, closed in 1993.

Post markings

Postal Rates from 1801 were charged depending on the distance from London. Durham was allocated the code 263 the approximate mileage from London. From about 1811, a datestamp appeared on letters showing the date the letter was posted. In 1844 a new system was introduced and Durham was allocated the code 267.[72] This system was replaced in 1840 when the first postage stamps were introduced.

Antiquities

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911): "To the Anglo-Saxon period are to be referred portions of the churches of Monk Wearmouth (Sunderland), Jarrow, Escomb near Bishop Auckland, and numerous sculptured crosses, two of which are in situ at Aycliffe. . . . The Decorated and Perpendicular periods are very scantily represented, on account, as is supposed, of the incessant wars between England and Scotland in the 14th and 15th centuries. The principal monastic remains, besides those surrounding Durham cathedral, are those of its subordinate house or "cell," Finchale Priory, beautifully situated by the Wear. The most interesting castles are those of Durham, Raby, Brancepeth and Barnard. There are ruins of castelets or peel-towers at Dalden, Ludworth and Langley Dale. The hospitals of Sherburn, Greatham and Kepyer, founded by early bishops of Durham, retain but few ancient features."[17]

The best remains of the Norman period include Durham Cathedral and Durham Castle, and several parish churches, such as St Laurence Church in Pittington. The Early English period has left the eastern portion of the cathedral, the churches of Darlington, Hartlepool, and St Andrew, Auckland, Sedgefield, and portions of a few other churches.[17]

'Durham Castle and Cathedral' is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site.[73] Elsewhere in the County there is Auckland Castle.[74]

Museums

Museums include North of England Lead Mining Museum, Beamish Museum, Bowes Museum, Head of Steam and the National Museum of the Royal Navy, Hartlepool.[75]

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Durham". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 706–708. The history of the county is covered on page 708.

- William Page (ed). The Victoria History of the County of Durham. James Street, Haymarket, London. Volume 1. 1905. Archibald Constable and Company Limited. London. Volume 2. 1907. The St Catherine Press. Stamford Street, Waterloo, London. Volume 3. 1928. Gillian Cookson (ed). A History of the County of Durham. (Victoria County History) Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research. Woodbridge. Volume 4. 2005. Volume 5. 2015.

- Tom Corfe, Don Wilcock and B K Roberts (ed). An Historical Atlas of County Durham. Durham County Local History Society. Hexham. 1992.

- ^ As to prehistoric Durham, see further Pocock and Norris, "Prehistoric Durham", A History of County Durham, Phillimore, 1990, chapter 2, p 14; Greenwell, "Early Man", Victoria County History, 1905, vol 1, p 199; W Boyd Dawkins, "Notes on Durham, York and Manchester in Prehistoric Times: Prehistoric Durham, York and Manchester" (1909) 66 The Archaeological Journal 171; Rosemary Annable, The Later Prehistory of Northern England: Cumbria, Northumberland, and Durham from the Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age, BAR British Series 160(1), 160(ii) and 160(iii), 1987, Parts 1, ii and iii; Robert Young, Lithics and Subsistence in North-eastern England: Aspects of the Prehistoric Archaeology of the Wear Valley, Co Durham, from the Mesolithic to the Bronze Age, BAR British Series 161, 1987

- ^ Peter Clack. "Early Settlement in the County". Elizabeth Williamson (ed). Nikolaus Pevsner. County Durham. (The Buildings of England). Second Edition. Penguin Books. 1983. 1985. Yale University Press. 2002. p 55.

- ^ Mortimer Wheeler, "The Brigantian Fortifications at Stanwyck, Yorkshire" in Mitford (ed), Recent Archaeological Excavations in Britain, 1956, Routledge, 2015, Chapter 3, p 43 at p 55. Cf. D W Harding, "Brigantia and northern England", The Iron Age in Northern Britain, Routledge, 2004, Chapter 2, p 23

- ^ As to Roman Durham, see further Boyle, "Durham in Roman Times", 1892, p 66; J A Petch, "Roman Durham" (1925) 1 Archaeologia Aeliana (Fourth Series) 1; K A Steer, The Archaeology of Roman Durham, University of Durham, 1938; Eric Birley, "Roman Durham" (1954) 111 The Archaeological Journal 194; Brian Dobson, "Roman Durham" (1970) 2 Transactions of the Architectural and Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland (New Series) 31; Brian Dobson, "The Roman Period" in J C Dewdney (ed), Durham County and City with Teesside, 1970, p 195; Frank Graham, Roman Durham, (Northern History booklet No 85), 1979; Pocock and Norris, "Roman Durham", A History of County Durham, 1990, p 18; and D J P Mason, Roman County Durham: The Eastern Hinterland of Hadrian's Wall, 2021.

- ^ As to the Anglo-Saxon period, see Rosemary J Cramp, "The Anglo Saxon Period" in J C Dewdney (ed), Durham County and City with Teesside, 1970, pp 199 to 206; Charles C Hodges, "Anglo Saxon Remains", Victoria County History, 1905, vol 1, pp 211 to 240; Rosemary J Cramp, Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture: Durham and Northumberland, British Academy, 1984, vol 1. As to the Early Medieval period, see Pocock and Norris, "Early Middle Ages and County Durham", A History of County Durham, Phillimore, 1990, chapter 4, p 22.

- ^ Charles C Hodges, "Anglo Saxon Remains", Victoria County History, 1905, vol 1, pp 211 to 240

- ^ a b c Gething, Paul (2012). Northumbria: The Lost Kingdom. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9089-2.

- ^ "Birth of Durham and Reign of Canute". englandsnortheast.co.uk.

- ^ a b Scammell, Jean (1966). "The Origin and Limitations of the Liberty of Durham". The English Historical Review. 81 (320): 449–473. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXI.CCCXX.449. JSTOR 561658.

- ^ Warren, W. L. (1984). "The Myth of Norman Administrative Efficiency: The Prothero Lecture". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 34: 113–132. doi:10.2307/3679128. JSTOR 3679128. S2CID 162793914.

- ^ a b c d e f Dodds (2005). Northumbria at War: War and Conflict in Northumberland and Durham (Battlefield Britain). Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-0-11-702037-5.

- ^ "The Harrying of the North | History Today". www.historytoday.com.

- ^ Douglas, D.C. William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England

- ^ As to Anglo-Norman Durham, see Rollason, Harvey and Prestwich (eds), Anglo-Norman Durham: 1093-1193, Boydell Press, 1994; Aird, St Cuthbert and the Normans, Boydell Press, 1998; Pocock, "Anglo-Norman Durham", The Story of Durham, 2013, chapter 2; "Anglo-Norman Durham: 1093-1193" (1992) 2 Medieval History; Rozier, "Compiling Chronicles in Anglo-Norman Durham" (2019) 42 Anglo-Norman Studies 119.

- ^ Dalton, Insley and Wilkinson. Cathedrals, Communities and Conflict in the Anglo-Norman World. 2011. pp 11 & 12

- ^ Fraser, C. M. (1956). "Edward I of England and the Regalian Franchise of Durham". Speculum. 31 (2): 329–342. doi:10.2307/2849417. JSTOR 2849417. S2CID 161266106.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Chisholm 1911, p. 708.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Durham historic boundaries[permanent dead link]. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ "History of County Durham | Map and description for the county, A Vision of Britain through Time". Vision of Britain. University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Islandshire Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine (historic map[dead link]). Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Norhamshire Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine (historic map[dead link]). Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Durham (Ancient): area Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007

- ^ a b c National Statistics – 200 years of the Census in... Durham Archived 3 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ P D A Harvey. "Boldon Book and the Wards between Tyne and Tees". Rollason, Harvey and Prestwich (eds). Anglo-Norman Durham: 1093-1193. Boydell Press. 1994. p 399

- ^ Lapsley, "Introduction to and Text of the Boldon Book", Victoria County History, 1905, vol 1, p 259

- ^ "The Prince Bishops of Durham". Durham World Heritage Site. 11 July 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Drummond Liddy, Christian (2008). The Bishopric of Durham in the Late Middle Ages. Boydell. p. 1. ISBN 978-1843833772.

- ^ The Durham (County Palatine) Act 1836 (6 & 7 Will 4 c 19)

- ^ The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. His Majesty's Statute and Law Printers. 1836. p. 130.

bishop of durham temporal Powers by Palatine Act 1836.

- ^ "The Bishops of Durham". Diocese of Durham. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Jarrow MB Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ a b Vision of Britain – West Hartlepool MB/CB Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ a b Bryne, T. (1994). Local Government in Britain. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-026739-6.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Darlington MB/CB Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Yorkshire, North Riding Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Stockton on Tees Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ Vision of Britain – Billingham UD Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ UK Census, 1971

- ^ Office for National Statistics (1999). Gazetteer of the old and new geographies of the United Kingdom. Office for National Statistics. ISBN 978-1-85774-298-5.

- ^ Her Majesty's Stationery Office (1996). Aspects of Britain: Local Government. Stationery Office Books. ISBN 978-0-11-702037-5.

- ^ a b Arnold-Baker, C., Local Government Act 1972, (1973)

- ^ a b Young, F. (1991). Guide to Local Administrative Units of England: Northern England. Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-86193-127-9.

- ^ Durham County Council – About Us: Council Logo Archived 14 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ Elcock, H., Local Government, (1994)

- ^ OPSI – Cleveland (Structural Change) Order 1995 Archived 2 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ OPSI – Cleveland (Further Provision) Order 1995 Archived 7 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ Lieutenancies Act 1997 Archived 19 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ Royal Mail, Address Management Guide, (2004)

- ^ Durham County Council – Local Government Review in County Durham Archived 14 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ "The County Durham (Structural Change) Order 2008". www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009.

- ^ "The Durham, Gateshead, Newcastle Upon Tyne, North Tyneside, Northumberland, South Tyneside and Sunderland Combined Authority Order 2014". The National Archives. 3 July 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ "The Newcastle Upon Tyne, North Tyneside and Northumberland Combined Authority (Establishment and Functions) Order 2018". www.legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ Nic Marko (10 May 2021), Four Hartlepool villages have 'no confidence' in borough council and want to join Durham, Hartlepool: Hartlepool Mail

- ^ "Bradford crowned UK City of Culture 2025". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ As to 18th century Durham, see Pocock and Norris, "Eighteenth-Century County Durham", A History of County Durham, 1990, chapter 7, p 41; Pocock, "Eighteenth-Century Durham", The Story of Durham, 2013, chapter 5; Phillips, "The friendship of the world: Female business networks in eighteenth-century Durham", Women in Business, 1700-1850, Boydell Press, 2006, chapter 5, p 95; Orde, "Ecclesiastical Estate Management in County Durham during the Eighteenth Century" (2008) 45 Northern History 159; Edward Hughes, "North Country Life in the Eighteenth Century" (1940) 25 History (New Series) 113, North Country Life in the Eighteenth Century: The North East, 1700—1750, OUP, 1952, vol 1; Fleming, "Harmony and Brotherly Love: Musicians and Freemasonry in 18th-Century Durham City" (2008) 149 The Musical Times 69; H W C Eisel, "A brief history of education in Durham County in the eighteenth century with special reference to elementary education", 1941.

- ^ Statistics of Dissent in England and Wales, 1842, p 49

- ^ Larson, Rethinking the Great Transition, p 1

- ^ Pocock and Norris, A History of County Durham, 1990, p 41. See further, An Account of the Rebellions in the Years 1715 and 1716; 1745 and 1746; So far as relates to the Counties of Northumberland and Durham, . . ., 1831 Google.

- ^ Dufferwiel, Durham: A Thousand Years of History and Legend, 1996, pp 109 to 112; Dodds, Secret City of Durham, 2016, chapter 38; Hall and Stead, A People's History of Classics [1]; Public Sculpture of North-East England, 2000, p 245. As to the schemes promoted by the statue, see further 58 Archaeologia Aeliana 118; Bonney, Lordship and the Urban Community, p 58; Mackenzie and Ross, 1834, p 352.

- ^ As to 19th century Durham, see Pocock, "Early Nineteenth-Century Durham" and "Victorian Durham", The Story of Durham, 2013, chapters 6 and 7; Pocock and Norris, "A Mining World" and "The Industrial Revolution", A History of County Durham, 1990, chapters 10 and 11, pp 56 & 61; Robert Lee, The Church of England and the Durham Coalfield, 1810-1926, 2007; Lee, "A Shock for Bishop Pudsey" and Milne, "Business Regionalism" in Green and Pollard (eds), Regional Identities in North-East England, 1300-2000, Boydell Press, 2000, chapters 4 and 5; Zon, "The Musical Scene at Durham Cathedral", Nineteenth-century British Music Studies, 1999, vol 2, p 70.

- ^ As to the political history of County Durham, see "Political History", Victoria County History, 1907, vol 2, pp p 133 to 173; Alan Young, William Cumin: Border politics and the Bishopric of Durham, 1141-1144, Borthwick Papers No 54, 1978.

- ^ Victoria County History, 1907, vol 2, p 139

- ^ Victoria County History, vol 2, p 1. As to the ecclesiastical history of Durham, see Henry Gee, "Ecclesiastical History", Victoria County History, 1907, vol 2, p 1.

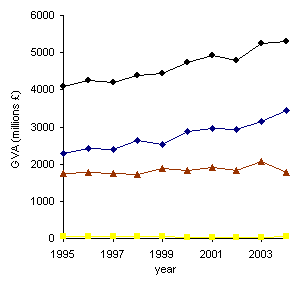

- ^ "NUTS3 GVA (1995–2004) Data". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 3 March 2005. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ a b "Coal Mining and Durham Collieries". www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk. 28 November 2016.

- ^ "About Coal Mining in County Durham". www.durhamintime.org.uk.

- ^ "History of Railways in County Durham - Waggonways". sites.google.com.

- ^ "Coal Mining in North East England". englandsnortheast.co.uk.

- ^ "Life in the booming railway town". Locomotion.

- ^ Pattison, Gary (2004). "Planning for decline: The 'D'-village policy of County Durham, UK". Planning Perspectives. 19 (3): 311–332. Bibcode:2004PlPer..19..311P. doi:10.1080/02665430410001709804. S2CID 220326166.

- ^ "Category-D villages in County Durham Waggonways". sites.google.com.

- ^ Hendy, The History of the Postmarks of the British Isles from 1840 to 1876, 1909, p 166

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Durham Castle and Cathedral". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ Pettifer, English Castles, 1995, p 25

- ^ Reynard (ed), Directory of Museums, Galleries and Buildings of Historic Interest in the United Kingdom, 3rd Ed, 2003, p 2354.