Hercules (1829 ship)

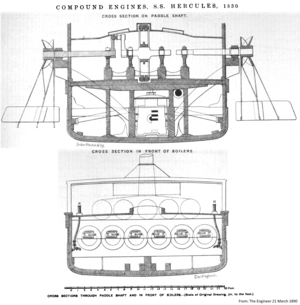

Cross sections of Hercules | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Hercules |

| Namesake | Hercules |

| Builder | |

| Launched | June 1827[1] |

| Stricken | Broken up in Dordrecht c. 1870[2] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Paddle steamboat |

| Length | 175 ft 2 in (53.39 m)[3] |

| Beam | 23 ft (7.0 m) (see drawings) |

| Installed power | 200 hp (150 kW)[4] |

| Propulsion | 2 paddle wheels |

Hercules was a Dutch steam paddle tugboat. She was also the first vessel to effectively use a compound steam engine. In about 1890, a discussion about the invention of the compound steam engine made that Fijenoord brought up the blueprints of Hercules. These proved that Gerhard Moritz Roentgen had invented the compound steam engine.

Construction

Context

In late 1815 the Dutch navy officer Gerhard Moritz Roentgen had arrived in England on board a ship of the line that was destined to the Dutch East Indies. This ship was in such a bad state that it did not get further than Portsmouth. It all led to Roentgen getting multiple assignments to study the British shipbuilding and iron industry. Roentgen became an expert in these fields, and in early 1824 Roentgen and others founded the Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij (NSM).

In April 1824 Roentgen sent in a report about the use of steam power on warships. He proposed that the government should promote or execute three projects. One of these was the construction of tugboats to tow warships on rivers, into sea, and even into the English Channel. Two others were about converting an existing warship to steam power, and about constructing a new steam powered warship. These latter projects would fail.

In 1825 the Dutch government offered the NSM a loan if it would build a tugboat for use on the rivers and at sea. The loan was 200,000 guilders at 3% to be repaid in 12 years.[5] Meanwhile, the NSM expanded its capital in order to realize four projects. One of these was again: A tugboat for service on the rivers and close to sea.[6]

Problematic construction

By 31 August 1825 the tug was under construction.[7] Hercules was launched in June 1827 in Boom, south of Antwerp.[1] In Boom F. de Center built a steamboat that was bought by NSM. Therefore, this shipyard might also be a candidate to have built Hercules.[8] NSM's big shipyard Fijenoord was founded only in 1827. Lack of funding caused that by 1828 Hercules was still not ready.[9]

The overview that had Boom as construction site for Hercules, also shows that the steamboat Agrippina had been launched for the „Preußisch-Rheinische Dampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft“ (PRDG) in Cologne (later Köln-Düsseldorfer) in March 1827, and that it was of the same size, i.e. 300 ton.[1] Furthermore, NSM had designed both, but would herself build the machines for Hercules, while Taylor & Martineau built those for Agrippina.[10] When Agrippina proved unsuitable for the PRDG, Roentgen decided to place the steam engine (but not the boilers) of the failed Agrippina in Hercules.[9]

Invention of the compound steam engine

The engine of Agrippina was a high pressure steam engine. Its two high pressure cylinders had a diameter of 21 inch and a 5 feet stroke.[11] In a first plan Roentgen wanted to add two low pressure cylinders, but this was found to be too expensive.[12] Roentgen then got the idea to add a single large low pressure cylinder. The low-pressure cylinder would re-use the steam of the high-pressure cylinders, which would otherwise escape into the atmosphere.[9] The low-pressure cylinder came from the failed ocean liner Atlas. Its diameter was 4 feet 6 inch.[13] In March 1829 a shaft for the low-pressure cylinder was to be made from a shaft taken from James Watt.[11]

This combination of high- and low-pressure cylinders was not new. It had been invented and was in use as a Woolf Engine. The essential difference with Roentgen's compound steam engine was that Roentgen used a receiver, which received the steam used by the high pressure cylinders while the intake of the low-pressure cylinder was still closed. This is the essential difference between a Woolf Engine and a compound steam engine.[9]

The Dutch Professor Harry Lintsen (1949+) made a reconstruction of how the compound steam could be invented in the then backwards Netherlands. He noted that Fijenoord / NSM's repair ship was led by N.O. Harvey (1801-1861). Harvey's uncle H. Harvey owned a machine factory and foundry in Hayle, Cornwall. At this factory, Arthur Woolf worked on perfecting the Woolf Engine. Furthermore, an aunt of Harvey Jr., Jane Harvey, married Richard Trevithick, who visited Fijenoord in 1828. It is known that Roentgen and N.O. Harvey made all kinds of plans to use Woolf engines on ships. The result was a 'Dutch' invention of the compound steam engine.[14]

(Re)launch

On 26 June 1829 Roentgen gave a general order to hasten the work on Hercules as much as possible, so that she could be launched again.[11] A second launch seems strange, but Fijenoord indeed had a patent slip, which had e.g. pulled the German steamboat Concordia out of the water for repairs in 1827.

Service

First service on the Rhine

When Hercules was put into service, her compound engine was not yet ready, and she had to use the high pressure cylinders only.[12] On 17 August 1829 Hercules left Rotterdam for Düsseldorf towing Agrippina, which had been turned into a dumb barge which also had luxury passenger accommodation.[15] On 20 August the combination reached Düsseldorf where grand duchess Helen of Russia disembarked.[16] The combination now seems like a stopgap solution, but it in effect made it legal to use a high-pressure steam engine for passenger transport.

The service of Hercules and Agrippina was regularly scheduled for September 1829.[17] However, the size of both vessels made this combination troublesome.[18] Hercules was next changed for a different mode of transport. She would herself carry about 2,000 hundred weight of cargo. This left capacity to still tow 4-6 regular sailing barges. These were towed upstream to Emmerich, or even Düsseldorf.

From about mid October 1829 Hercules and the other NSM tugboat, De Stad Keulen were both planned to serve between Antwerp and Cologne.[19][20] On her first trip from Antwerp, Hercules and her train transported 170 lasts of cargo, and it was believed that this could grow to 250 lasts.[21] By April 1830 both tugboats were said to transport up to 10,000 hundredweight in a single trip, carrying cargo in their own hold as well as in barges.[22]

In November 1829 Hercules made a trip from Antwerp to Cologne and became grounded on one of the Dutch rivers from 17 to 19 November.[23] It led to a complaint in a German newspaper about the transport with tugboats, which then only brought their barges to Emmerich.[24] From the discussion we know that by March 1830 Hercules was already towing multiple barges instead of the single Agrippina.[23] These barges were indeed sailing vessels, even though Hercules towed them up to Emmerich.[25]

Service during the Belgian revolution

The Belgian Revolution took place from 25 August 1830 to 21 July 1831. By October 1830 the Dutch army in Belgium had disintegrated. However, the Antwerp Citadel and the Scheldt fortresses Fort Lillo and Fort Liefkenshoek remained in Dutch hands. The Dutch government then hired multiple steamboats to maintain connections to Antwerp, and to block the Scheldt. One of these vessels was Hercules. On 11 November 1830 she arrived in Vlissingen from Rotterdam.[26] On 17 May 1831 Hercules arrived at Fort Lillo, towing 9 barges of food for the fortresses and the citadel.[27]

In August 1831 a French army stopped the Ten days' campaign of the Dutch government against the Belgian rebels. In November 1832 the French army then started the Siege of Antwerp. On 10 December 1832 Hercules was commanded by lieutenant 2nd class Van Vloten. She was positioned at the Kruisschans, east of Lillo, near Oorderen on the Scheldt. She was positioned close to the frigate Euridice.[28] The siege of Antwerp ended on 23 December 1832. In January 1833 the steamboats Curaçao, Beurs van Amsterdam and Hercules towed Eurydice, and the corvettes Medusa and Komeet down the Scheldt.[29] On 13 April 1833 Hercules towed the ship of the line De Zeeuw from Vlissingen to Walsoorden.[30] In June she towed the dismasted ship De Vrede into the dock of Vlissingen.[31] On 21 June 1833 Hercules towed five barges from Middelburg to Dordrecht, and then Gorinchem. On board were elements of the Dutch garrison of Antwerp, who got a hero's welcome in that town.[32] After the military service had ended, the compound engines of Hercules were finished.[12]

Tug service

In 1832 the government tug service for the Waal was founded. It stretched from Rotterdam to Lobith, and it was executed by the NSM.[33] In 1833 the service was only profitable for NSM because Hercules had a newly invented engine that saved one-third of the normally required fuel.[34] The service boosted the harbor of Rotterdam, and especially the export of colonial produce to Germany. This led to a state subsidy for the tug service on the Rhine.[18] The contract between the state and NSM was to end in 1848. It was nevertheless renewed in June 1849.[35] The reasoning behind this was that the tug service led to less maintenance on the many towpaths along the Lek. The contract for the government steam tug service on the Waal finally ended on 1 January 1858.[36] Up till that time Hercules was regularly involved in the steam tug service.

It seems that NSM also made an attempt to use Hercules as a sea-going tug. In September 1833 she towed the frigate De Dortenaar into Hellevoetsluis.[37] In March 1834 she first towed the merchant frigate De Koophandel from Vlissingen to Rotterdam, and then De Schelde.[38]

On 15 or 16 March 1835, Hercules passed Emmerich towing the barges: Koophandel, skipper Von Böningen (2,961 cwt) destined to Coblenz; Harmonie skipper H. Köhler (3,453 cwt) to Mannheim; and that of skipper Schmitz (3,395 cwt) also to Mannheim.[39] On 17 March 1835 Hercules was seen before Düsseldorf towing four heavily loaded barges aligned in two pairs behind each other. This was an experiment that made the news.[40] The enormous power of Hercules was noted.[41] On 19 March Hercules brought Koophandel, Harmonie, and two barges of 1,930 cwt and 3,305 cwt into the harbor of Cologne.[42] The heavier train confirms that the compound engines of Hercules were not yet finished when she was on the Rhine before the Belgian revolution. On 1 June, she towed the East Indies ship Stad 's Gravenhage into Hellevoetsluis. In 1836 Hercules also served on the Rhine, as was the case in 1838.[43]

In March 1840 Hercules was involved in a successful attempt to lift De Stad Keulen, which had sunk after a collision near Millingen aan de Rijn.[44]

In time, NSM got more powerful and efficient vessels to tow vessels on the Rhine. In December 1843 Hercules towed the East Indies ship Gertrude from Hellevoetsluis into sea.[45] In 1845 and 1846 Hercules still did such jobs, even though she had got competition from the tug Kinderdijk of L. Smit & Co. It seems that Hercules was then put to service more inland. In 1853 Hercules was involved in lifting the steamer Gironde captain M.J. Frantzen from Bordeaux, which had become stuck before Vlaardingen.[46] In April 1853 she assisted the French steamer Hambourg captain Choix from Le Havre, which had become stuck in the Oude Maas.[47] In June 1856 she towed the Amsterdam three mast brig Prinses Amelie captain W. Groeneveld. Near Rotterdam this brig fell over while under tow, but was soon put upright again.[48]

Fate

Hercules seemed to have been broken up in Dordrecht in about 1870.[2]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Hermes 1828, p. 58.

- ^ a b Walter Pearce 1890, p. 234.

- ^ Sleepvaartmuseum 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Eckert 1900, p. 254.

- ^ Löhnis 1916, p. 139.

- ^ "Deelneming in de Nederlandsche Stoomboot-Maatschappij". Utrechtsche courant. 25 April 1825.

- ^ Löhnis 1916, p. 136.

- ^ Hermes 1828, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Lintsen 1994, p. 224.

- ^ Hermes 1828, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Walter Pearce 1890, p. 296.

- ^ a b c Lintsen 1994, p. 229.

- ^ Walter Pearce 1890, p. 295.

- ^ Lintsen 1994, p. 228.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 17 augustus". Rotterdamsche courant. 18 August 1829.

- ^ "Preußen". Kölnische Zeitung. 12 September 1829.

- ^ "Nederlandsche Stoombot-Maatschapij". Arnhemsche courant. 12 September 1829.

- ^ a b Eckert 1900, p. 253.

- ^ "Advertisements". Kölnische Zeitung. 18 October 1829.

- ^ "Advertisements". Kölnische Zeitung. 31 October 1829.

- ^ "Inland". Stadt Aachener Zeitung. 24 December 1829.

- ^ "Inland". Kölnischer Correspondent. 26 April 1830.

- ^ a b "Carga Lijsten". Algemeen Handelsblad. 24 March 1830.

- ^ "Amsterdam, den 23 Februarij 1830". Algemeen Handelsblad. 24 February 1830.

- ^ "Amsterdam, den 23 April 1830". Algemeen Handelsblad. 24 April 1830.

- ^ "Zee-tijdingen". Middelburgsche courant. 16 November 1830.

- ^ "Dagorder". Groninger courant. 27 May 1831.

- ^ "Binnenlandsche Berigten". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 14 December 1832.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 9 januarij". Rotterdamsche courant. 10 January 1833.

- ^ "Extracten uit de Belgische dagbladen". Algemeen Handelsblad. 29 April 1833.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 12 junij". Rotterdamsche courant. 13 June 1833.

- ^ "Binnenlandsche Berigten". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 26 June 1833.

- ^ "Mengelwerk". Arnhemsche courant. 22 March 1834.

- ^ "IJzeren Spoorweg". Algemeen Handelsblad. 29 August 1834.

- ^ NSM 1850, p. 3.

- ^ Löhnis 1916, p. 148.

- ^ "Binnenlandsche Berigten". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 27 September 1833.

- ^ "Nederlanden". Bredasche courant. 11 March 1834.

- ^ "Keulen, 19 Maart". Nederlandsche Staatscourant. 23 March 1835.

- ^ "Dusseldorp, den 18. maart". Middelburgsche courant. 24 March 1835.

- ^ "Düsseldorf, 17. März". Statdt Aachener Zeitung. 20 March 1835.

- ^ "Binnenlandsche Berigten". Algemeen Handelsblad. 26 March 1835.

- ^ "Vaart op den Rijn". De Avondbode. 5 June 1838.

- ^ "Buitenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 13 March 1840.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 27 december". Rotterdamsche courant. 28 December 1843.

- ^ "Rotterdam, 15 Maart". Algemeen Handelsblad. 16 March 1853.

- ^ "Rotterdam, 27 April". Algemeen Handelsblad. 28 April 1853.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 13 junij". Rotterdamsche courant. 14 June 1856.

Bibliography

- Eckert, Christian (1900), "Rheinschiffahrt im XIX. Jahrhundert", Staats- und sozialwissenschaftliche Forschungen, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig

- Lintsen, H.W. (1993), Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890, vol. III

- Lintsen, H.W. (1994), Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890, vol. V

- Löhnis, Th. P. (1916), "De Maatschappij voor scheeps- en werktuigbouw Fijenoord te Rotterdam, voorheen de Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij", Tijdschrift voor economische geographie, pp. 133–156

- Van Jagen naar onbemand, Nationaal Sleepvaart Museum, 2017

- NSM (1850), Verslag van den direkteur der Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij aan de Algemene Vergadering

- Walter Pearce, I. (1890), "Compound marine engines sixty years ago No. I", The Engineer, pp. 232–234, 241–242, 278, 294–296, 355, 364, 401–402, 524–526

- "Iets over stoom-vaartuigen", De Nederlandsche Hermes, tijdschrift voor koophandel, zeevaart en, no. 8, M. Westerman, Amsterdam, pp. 53–63, 1828