Hamon (swordsmithing)

In swordsmithing, hamon (刃文) (from Japanese, literally "edge pattern") is a visible effect created on the blade by the hardening process. The hamon is the outline of the hardened zone (yakiba) which contains the cutting edge (ha). Blades made in this manner are known as differentially hardened, with a harder cutting edge than spine (mune) (for example: spine 40 HRC vs edge 58 HRC). This difference in hardness results from clay being applied on the blade (tsuchioki) prior to the cooling process (quenching). Less or no clay allows the edge to cool faster, making it harder but more brittle, while more clay allows the center (hira) and spine to cool slower, thus retaining its resilience.[1]

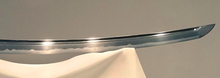

Hamon does not refer to the white area on the side of the blade. The white part is the part that is whitened by a polishing process called hadori to make it easier to see the hamon, and the actual hamon is a fuzzy line within the white part. The actual line of the hamon can be seen by holding the sword in your hand and looking at it while changing the angle of the light shining on the blade.[2][3]

Hamons were developed by and traditionally found in Japanese swordsmithing. Similar features are often found in knives and swords from the West and are sometimes called temper lines, although these are not often produced with clay but by other means such as partial quenching, flame hardening, or differential tempering, which produces many differences from a traditional hamon. A true hamon, and many of its key features such as a nioi, have no direct translation into English, thus the Japanese terms are usually used when referring to clay-quenched blades.[4]

Introduction

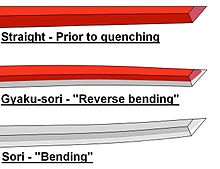

The hamon of a blade is created during the quenching process (yakiire). During the differential heat treatment, the clay coating on the back of the sword reduces the cooling speed of the red-hot metal when it is plunged into the water and allows the steel to turn into pearlite, a soft structure consisting of cementite and ferrite (iron) laminations. On the other hand, the exposed edge cools very rapidly, changing into a phase called martensite, which is nearly as hard and brittle as glass.

The hamon outlines the transition between the region of harder martensitic steel at the blade's edge and the softer pearlitic steel at the center and back of the sword. This difference in hardness is the objective of the process; the appearance is purely a side effect. However, the aesthetic qualities of the hamon are quite valuable—not only as proof of the differential-hardening treatment but also in its artistic value—and the patterns can be quite complex.[5]

In English, the terms "hamon" and "temper line" are sometimes used interchangeably, although subtle differences do exist, but both tend to refer to the entire line. In Japanese, however, "hamon" refers strictly to the pattern along the length of the blade, whereas the hamon at the tip (kissaki) is called the boshi.[6]

Types

The shape of the hamon is affected by many factors, but is primarily controlled by the shape of the clay coating at the time of quenching. Although each school had its own methods of application, and kept secret the process, the exact mixture of the clay, the thickness of the coat, and even the temperature of the water, the clay was usually applied by painting it on in very thin layers, to help prevent shrinking, peeling, and cracking as it dried. Often, the clay is applied to the entire blade by piling up the layers very thickly over the entire sword, and then the clay was carefully cut away from the edge. However, in ancient times tempering was rarely used in Asia, and a fully exposed edge would cool too fast and become far too brittle, thus a thinner layer of clay was usually applied to the edge so as to achieve the correct hardness upon quenching without the need for tempering afterwards.

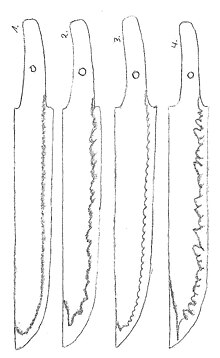

The smith shapes the hamon at the time of coating the blade. There are two basic styles, which are "straight edge" (sugaha) and "irregular pattern" (midare or midareba). Straight-edge hamons simply follow the edge of the sword with little deviation, except at the tip. This was by far the most popular style in every era and in every province, whereas the more complex patterns that were in themselves works of art tended to be reserved for the wealthy and elite. Straight patterns are usually classified by the width of the hardened zone (yakiba), and divided into "wide" (hiro), "medium" (cho), "narrow" (hoso), and extremely narrow or "string" (ito) hamons.

Conversely, irregular hamons do not simply follow the edge, but deviate from it considerably in various ways. The two main groups are "undulating" or "wavy" (notare) and tooth-like or "zig-zag" (gunome), and these are often classified by the wavelength or breadth of the irregularities. Sometimes hamons can consist of one style, a mixture of two, or all three (e.g. gunome midare, notare midare, toran midare, etc.), with many other differences sometimes added in for effect. Kataochi gunome resembled saw teeth, whereas uma-no-ha gunome resembled horse teeth. Fukushiki gunome consists of multiple sizes and shapes of teeth mixed with areas of regularly sized and shaped teeth. Toran midare appears as a combination of tooth and wave, resembling rows of plunging breaking waves. Koshi-no-hiraita midare consists of waves with wide valleys and steep crests, and were mainly found on Bizen swords of the Muromachi period.

The specific shape and style of the hamons were often unique and served as a sort of signature of the various swordsmithing schools or even for individual smiths that produced them. Kataochi gunome originated with Osafune Kagemitsu and was carried on by Kunimitsu, whereas togari gunome (very orderly and pointed peaks) were mainly found on swords of the Sue-Seki school. On the most ancient swords, the hamon typically ended just before the sword guard, but on most later and contemporary swords the hamon extends far past the guard, under the handle, and ends with the tang, which provided added strength to the tang.[7]

The shape of the hamon is affected by other factors as well. If a sword is made of a composite steel (as most ancient swords were) consisting of alternating layers of steel with different carbon contents, then the steel with higher hardenability will change into martensite deeper underneath the clay coating than the lower-carbon steel. This leaves a pattern of bright streaks that jut a short distance away from the hamon, called niye, which give it a wispy, misty, or foggy appearance. Likewise, complex swords that consist of sections of different steels welded together may show evidence of the welds near the hamon.[8]

Origins

China was the first country to produce iron in Asia, around 1200 BC. The Chinese developed cast iron, and from this developed processes of making wrought iron, mild steel, and crucible steel. For a period of over 1000 years, from the first to the eleventh century, China was the world's largest producer and exporter of steel and iron.[9][10] Nearly all metals then were imported into Japan from China, through Korea, including swords and weapons. Iron-making technology was typically a closely guarded secret, but was eventually imported into Japan from China around 600 or 700 AD, albeit with only a small amount of information to build on, so the ancient smiths began by trying to reverse engineer the Chinese methods, coming up with very different processes in the end.[11]

The Chinese swords had edges made of crucible steel similar to the metal found in Damascus swords, which were welded to a back of soft iron, to give both a hard and strong cutting edge but keeping the rest of the sword soft to prevent breakage. These produced a very hard and visible patterned-edge with a very visible transition at the weld, due to the different composition of the steels, despite the lack of any form of heat treatment. In tying to imitate the Chinese swords, the Japanese came up with unique processes and their own methods of creating a visible hardened edge, taking the Chinese methods and "refining them beyond recognition". The earliest swords forged in Japan (tsurugi and chokutō) reflect the similarities between the Japanese and Chinese swords of the time.[11]

According to legend, Amakuni Yasutsuna developed the process of differentially hardening the blades around the 8th century AD, around the time that the tachi (curved sword) became popular. The emperor was returning from battle with his soldiers when Amakuni noticed that half of the swords were broken:

Amakuni and his son, Amakura, gathered up the broken blades and examined them. They were determined to create a blade that would not break in combat and locked themselves away in seclusion for 30 days. When they reappeared, they carried with them the curved blade. The following spring there was another war. Again the soldiers returned, only this time all the swords were intact and the emperor smiled on Amakuni.[12]

Although impossible to ascertain who actually invented the technique, surviving blades by Amakuni from around 749–811 AD suggest that at the very least Amakuni helped establish the tradition of differentially hardening the blades.[12]

In the most ancient swords, all hamons were of the straight-edge variety. Irregular patterns started to emerge around the 1300s, with famous smiths such as Kunimitsu, Muramasa, and Masamune, among many others. By the 17th century, hamons with various shapes in them became common, such as trees, flowers, rat's feet, clovers, pillboxes, and many others. Common themes included juka choji (multiple, overlapping clovers), kikusui (chrysanthemums floating on a stream), Yoshino (cherry blossoms on the Yoshino River), or Tatsuta (maple leaves on the Tatsuta River). By the 1800s, with the addition of decorative forging techniques, hamons were being created that depicted entire landscapes. These often depicted specific scenery or skylines familiar in everyday life, such as specific islands or mountains, towns and cities, grassy countrysides, or violent crashing waves in the ocean complete with sandy beaches and spraying surf. A common such design was Fujimi Saigyo (Priest Saigyo viewing Mount Fuji). Sometimes low spots were cut into the clay to produce niye disconnected from the hamon in the center of the blade, creating the appearance of stars, clouds, wind-blown snowy peaks, or even birds in the sky.[8][13]

Modern reproductions

Many modern reproductions do not have natural hamon because they are thoroughly hardened monosteel; the appearance of a hamon is reproduced via various processes such as acid etching, sandblasting, or more crude ones such as wire brushing. Some modern reproductions with natural hamons are also subjected to acid etching to enhance their hamons' prominence.

A true hamon can be easily discerned by the presence of a nioi, which is a bright speckled line a few millimeters wide, following the length of the hamon. The nioi is one of many features of Japanese swords that are sensitive to the viewing angle, seeming to appear and disappear when moved with respect to the light. Between the hardened edge and the hamon, the nioi creates the actual boundary between the martensite and the pearlite, but is indistinguishable from the martensite in direct light. It is typically best viewed at long or grazing angles where it appears brighter than the hardened edge. The nioi cannot be faked with etching or other methods. When viewed through a magnifying lens, the nioi appears as a sparkly line, being made up of many bright martensite grains which are surrounded by darker, softer pearlite.[1]

Many modern blades, especially those produced in Europe and the Americas, have hardened edges that are made using very different methods than insulating the blade with clay. The most common of these was independently discovered after the invention of the oxy-gas torch. Flame hardening is a method of rapidly heating only the edge with a torch and then quenching before the heat can thermally conduct to the rest of the blade. This creates a very hard edge without affecting the hardness of the rest of the blade, and upon polishing will leave a very visible transition between the harder and softer metals (usually martensite and tempered martensite rather than pearlite). This transition resembles a hamon and may sometimes be referred to as such, but is more commonly called the "temper line" (although it is actually produced upon quenching rather than tempering).[14][15] A flame-hardened temper line is easily discernible from a true hamon, which produces a nioi that provides a very tough boundary between the martensite and the pearlite. Flame hardening lacks a nioi and instead produces a very brittle zone between the harder and softer metals, called the heat affected zone (HAZ), caused by internal stresses and extremely rapid cooling between the hot and cold areas. Therefore, while flame hardening and temper lines are common in hand-made knives, they are rarely found in swords or weapons where a lot of shear and impact forces may be encountered.[16]

See also

References

- ^ a b Smith, Cyril Stanley (1968). A History of Metallography. MIT Press. pp. 40–57.

- ^ 備前長船刀剣博物館に関しての対談2 (in Japanese). Bizen Osafune touken Museum/Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Expressway Company. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ いろんな刃文を観てみる (in Japanese). The Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum "Nagoya Touken World". Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ Blade Magazine

- ^ Kokan Nagayama (1997). The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. p. 91.

- ^ Kokan Nagayama (1997). The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. p. 91.

- ^ Kokan Nagayama (1997). The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. pp. 91–106.

- ^ a b Smith, Cyril Stanley (1960). A History of Metallography. MIT Press. pp. 50–52, 57–61.

- ^ Donald B. Wagner, Donald B. "The Traditional Chinese Iron Industry and its Modern Fate".

- ^ Joseph Needham. Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5. p. 345

- ^ a b Smith, Cyril Stanley (1960). A History of Metallography. MIT Press. p. 41

- ^ a b Steve Shackleford Spirit of the Sword:A Celebration of Artistry and Craftsmanship. Chapter 5: "How to Clay Temper and Obtain a Beautiful 'Hamon'".

- ^ Kokan Nagayama (1997). The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. pp. 92–96

- ^ Blade Magazine

- ^ Blades Guide to Making Knives By Joe Kertzman – Krause Publications 2005 p. 47

- ^ Steel Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist By John D. Verhoeven – ASM International 2007 p. 51