HMS Glasgow (1909)

Glasgow about 1911 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Glasgow |

| Namesake | Glasgow |

| Builder | Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering, Govan |

| Laid down | 25 March 1909 |

| Launched | 30 September 1909 |

| Completed | September 1910 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 29 April 1927 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | Town-class light cruiser |

| Displacement | 4,800 long tons (4,877 t) |

| Length | |

| Beam | 47 ft (14.3 m) |

| Draught | 15 ft 3 in (4.65 m) (mean) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbines |

| Speed | 25 kn (46 km/h; 29 mph) |

| Range | 5,830 nautical miles (10,800 km; 6,710 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 480 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

HMS Glasgow was one of five ships of the Bristol sub-class of the Town-class light cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the first decade of the 20th century. Completed in 1910, the ship was briefly assigned to the Home Fleet before she was assigned to patrol the coast of South America. Shortly after the start of the First World War in August 1914, Glasgow captured a German merchant ship. She spent the next several months searching for German commerce raiders. The ship was then ordered to join Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock's squadron in their search for the German East Asia Squadron. He found the German squadron on 1 November off the coast of Chile in the Battle of Coronel. They outnumbered Cradock's force and were individually more powerful, sinking Cradock's two armoured cruisers, although Glasgow was only lightly damaged.

The ship fell back to the coast of Brazil for repairs and to await reinforcements. They arrived in late November under the command of Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee and were considerably more powerful than the East Asia Squadron. After sailing to the Falkland Islands to refuel in early December, the British ships were surprised by the Germans who withdrew when they realized the number of ships that Sturdee had under his command. They pursued the retreating Germans and sank four of their five ships in the Battle of the Falkland Islands, with Glasgow helping to sink one of the German light cruisers. She was one of the ships tasked to hunt down the sole survivor which she finally did, together with another cruiser, in the Battle of Más a Tierra in March 1915.

Glasgow spent the next two years searching for commerce raiders and protecting Allied shipping off the South American coast, although she was unsuccessful in locating one commerce raider active in the South Atlantic in early 1916. The ship was transferred to the Adriatic Sea in mid-1918 and played a minor role in the Second Battle of Durazzo a few months later. She was reduced to reserve after the war ended, but later served as a training ship in 1922–1926 before she was sold for scrap in 1927.

Design and description

The Bristol sub-class[Note 1] were officially rated as second-class cruisers suitable for a variety of roles including both trade protection and duties with the fleet.[2] They were 453 feet (138.1 m) long overall, with a beam of 47 feet (14.3 m) and a draught of 15 feet 6 inches (4.7 m). Displacement was 4,800 long tons (4,900 t) normal and 5,300 long tons (5,400 t) at deep load. Twelve Yarrow boilers fed Glasgow's Parsons steam turbines, driving four propeller shafts, that were rated at 22,000 shaft horsepower (16,000 kW), for a design speed of 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph).[2] The ship reached 25.85 knots (47.87 km/h; 29.75 mph) during her sea trials from 22,406 shp (16,708 kW).[3] The boilers used both fuel oil and coal, with 1,353 long tons (1,375 t) of coal and 256 long tons (260 t) tons of oil carried, which gave a range of 5,830 nautical miles (10,800 km; 6,710 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[4] The ship had a crew of 480 officers and ratings.[2]

The main armament of the Bristols was two BL 6-inch (152 mm) Mk XI guns that were mounted on the centreline fore and aft of the superstructure and ten BL 4-inch (102 mm) Mk VII guns on single mountings amidships, five on each broadside. All these guns were fitted with gun shields.[2] The ships carried four Vickers 3-pounder (47 mm) saluting guns, while they were also equipped with two submerged 18-inch (450 mm) torpedo tubes, one on each broadside.[5] This armament was considered too light for ships of this size,[6] while the waist guns were subject to immersion in a high sea, making them difficult to work.[7]

The Bristols were considered protected cruisers, with an armoured deck providing protection for the ships' vitals. The deck was 2 inches (51 mm) thick over the magazines and machinery, 1 inch (25 mm) over the steering gear and 0.75 inches (19 mm) elsewhere. The conning tower was protected by 6 inches of armour, with the gun shields having 3-inch (76 mm) armour, as did the ammunition hoists.[8] As the protective deck was at waterline, the ships were given a large metacentric height so that they would remain stable in the event of flooding above the armoured deck. This, however, resulted in the ships rolling badly making them poor gun platforms.[7] One problem with the armour of the Bristols which was shared with the other Town-class ships was the sizable gap between the bottom of the gun shields and the deck, which allowed shell splinters to pass through the gap, giving large numbers of leg injuries in the ships' gun crews.[9]

Construction and career

Glasgow, the sixth ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy,[10] was laid down on 25 March 1909 by Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in their Govan shipyard. She was launched on 30 September[11] and completed on 19 September 1910,[12] under the command of Captain Marcus Hill.[13] The ship was initially assigned to the 2nd Battle Squadron of the Home Fleet, but was transferred to the 4th Cruiser Squadron on the south east coast of South America the following year.[11] Hill was relieved by Captain John Luce on 17 September 1912.[13] From March to August, Glasgow cruised the coasts of Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, making many port visits.[14]

When the First World War began on 3 August 1914, she was in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and captured the 4,247 GRT Hamburg Süd cargo ship Santa Catharina on 14 August.[14][15] A week later Glasgow rendezvoused with the armoured cruiser Monmouth at the Abrolhos Rocks. The ship continued to patrol and met up with armed merchant cruiser Otranto on 28 August and then Rear-Admiral Christopher Cradock's flagship, the armoured cruiser Good Hope, on 17 September off Santa Catarina Island. The squadron then proceeded to Montevideo, Uruguay. After coaling the squadron arrived at Punta Arenas, Chile, in the Strait of Magellan, on the 28th. They spent a day searching the area for any German ships before heading to the Falkland Islands where they arrived on 1 October. The squadron coaled there and then Glasgow, Monmouth and Otranto returned to the Tierra del Fuego area on another unsuccessful search for German ships. They proceeded to search up the southern coast of Chile as far as Vallenar. Good Hope joined them there on 27 October.[14]

Battle of Coronel

The squadron departed two days later, just as the elderly battleship Canopus arrived, Cradock ordering her to follow as soon as possible. He sent Glasgow to scout ahead and to enter Coronel, Chile to pick up any messages from the Admiralty and acquire intelligence regarding German activities. The cruiser began to pick up radio signals from the light cruiser SMS Leipzig on the afternoon of 29 October and delayed entering Coronel for two days with Cradock's permission to avoid being trapped by the fast German ships. A German supply ship was already there and radioed Spee that Glasgow had entered the harbour around twilight. The cruiser departed on the morning of 1 November, but Spee had already made plans to catch her when informed of her presence the previous evening.[16]

Glasgow departed Coronel at 09:15 after having picked up the squadron's mail and rendezvoused with the rest of the squadron four hours later. Cradock ordered his ships to form line abreast with a distance of 15 nautical miles (28 km; 17 mi) between ships to maximise visibility at 13:50 and steered north at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). At 16:17 Leipzig spotted Glasgow, the easternmost British ship, to its west and she spotted Leipzig's funnel smoke three minutes later. At 17:10 Cradock ordered his ships to head for Glasgow, the closest ship to the Germans. Once gathered together, he formed them into line astern, with Good Hope in the lead, steering south-easterly at 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) at 18:18. As the sixteen 21-centimetre (8.3 in) guns aboard the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were only matched by the two 9.2-inch (234 mm) guns on his flagship, he needed to close the range to bring his more numerous 6-inch guns to bear. The Force 7 winds and high seas, however, prevented the use of half of those guns as they were too close to the water. He also wanted to use the setting sun to his advantage so that its light would blind the German gunners. Vizeadmiral (Vice-Admiral) Maximilian von Spee, commander of the East Asia Squadron, was well aware of the British advantages and refused to allow Cradock to close the range. His ships were faster than the British, slowed by the 16-knot (30 km/h; 18 mph) maximum speed of Otranto, and he opened up the range to 18,000 yards (16,000 m) until conditions changed to suit him. The sun set at 18:50, which silhouetted the British ships against the light sky while the German ships became indistinguishable from the shoreline behind them.[17]

Spee immediately turned to close and signalled his ships to open fire at 19:04, when the range closed to 12,300 yards (11,200 m). Spee's flagship, Scharnhorst, engaged Good Hope while Gneisenau fired at Monmouth. The German shooting was very accurate, with both armoured cruisers quickly scoring hits on their British counterparts while still outside six-inch gun range, starting fires on both ships. Cradock, knowing his only chance was to close the range, continued to do so despite the battering that Spee's ships inflicted. After disabling Monmouth around 19:35, Spee ordered his armoured cruisers to concentrate their fire on Good Hope when she continued to try to close the range. About 19:50 her forward magazine exploded and blew off her bow; she sank not long afterwards.[18]

Glasgow fought almost an entirely separate battle as the German armoured cruisers generally ignored her and she inconclusively duelled the light cruisers Leipzig and Dresden. Glasgow broke contact with the German squadron at 20:05 and discovered Monmouth, listing and down by the bow, having extinguished her fires, 10 minutes later. She was trying to turn north to put her stern to the heavy northerly swell and was taking water at the bow. There was little that Glasgow could do to assist the larger ship as the moonlight illuminated both ships and the Germans were searching for them. He broke contact with her at 20:50 and was finally able to report to Canopus the results of the battle. Around 21:20, the ship's crew spotted a searchlight beam and gun flashes behind them and knew that the Germans had finished off Monmouth. Considering that an estimated 600 shells were fired at her, Glasgow was only lightly damaged by five hits, of which the most serious was a shell that detonated on the waterline and tore a hole about 6 square feet (0.56 m2) in size that flooded one compartment. The ship's casualties numbered four lightly wounded ratings and some parrots that the crew had purchased. In return, she failed to hit any of the German ships.[19]

Battle of the Falkland Islands

Glasgow passed through the Strait of Magellan on 4 November and awaited Canopus at its eastern entrance. The battleship rendezvoused with her two days later and they steamed for Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands together. After arriving on the 8th, Canopus was ordered to ground herself in the harbour while the light cruiser continued north and met the armoured cruiser Defence at the River Plate and they sailed to Abrolhas Rocks to await reinforcements.[20] Glasgow stopped in Rio de Janeiro for repairs 16–21 November and arrived at the rocks two days later where Defence, the armoured cruisers Kent, Carnarvon and Cornwall and the armed merchant cruiser Orama awaited her. Glasgow's sister ship Bristol arrived the following day[14] and the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible, under the command of Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee reached the rocks on 26th. He planned to remain there for three days but was persuaded by Luce to depart on the morning of the 28th.[21]

Upon arrival at Port Stanley on 7 December, Sturdee informed his captains that he planned to recoal the entire squadron the following day from the two available colliers and to begin the search for the East Asia Squadron, believed to be running for home around the tip of South America, the day after. Vice-Admiral Maximilian von Spee, commander of the German squadron, had other plans and intended to destroy the radio station at Port Stanley on the morning of 8 December. The appearance of two German ships at 07:30 caught Sturdee's ships by surprise; the observation post telephoned Canopus with the information, but the battleship could not see Sturdee's flagship to relay the information, only Glasgow. Canopus hoisted the signal "Enemy in sight" and the light cruiser repeated the message at 07:56, but Invincible's crew was busy loading coal and did not spot the signal. Luce ordered a saluting gun fired to focus attention on the signal. Glasgow had completed coaling at 08:00 but needed time to finish raising steam.[22]

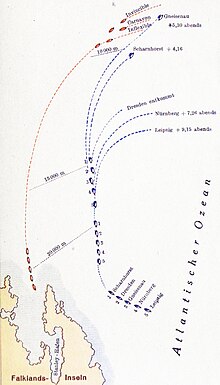

The Germans were driven off by 12-inch (305 mm) shells fired by Canopus when they came within range around 09:20. Glasgow cleared the harbour by 09:45 and was ordered by Sturdee to trail Spee's ships, keeping out of range, and to inform him of their actions. The last of the British ships left the harbor by 10:30 and Sturdee ordered "General chase". The battlecruisers were the fastest ships present and inexorably began to close on the German ships. They opened fire at 12:55 and started near-missing Leipzig, the rear ship in the German formation, 15 minutes later. It was clear to Spee that his ships could not outrun the battlecruisers and that the only hope for any of his ships to survive was to scatter. So he turned his two armoured cruisers around to buy time by engaging the battlecruisers and ordered his three light cruisers to disperse at 13:20. As soon as Luce spotted the light cruisers turn away, he turned to pursue them, followed by Kent and Cornwall.[23]

Glasgow, the fastest of the British ships, slowly increased her lead over the two armoured cruisers and Luce opened fire on Leipzig with his forward six-inch gun at 14:45 at a range of about 12,000 yards (11,000 m). One of his shells struck the German ship and she turned to allow her broadside guns to fire back. The first salvo narrowly missed Glasgow and she was hit twice in the next salvo, forcing Luce to fall back. This was repeated several times which allowed the two armoured cruisers to make up some of the distance. An hour later, the Germans scattered in different directions; Cornwall and Glasgow pursued Leipzig while Kent went after Nürnberg. Cornwall closed on the German ship at full speed, trusting to her armour to keep out the 105-millimetre (4.1 in) shells, while the unarmoured Glasgow manoeuvred at a distance. At 18:00 and Cornwall's shells set Leipzig on fire. Five minutes later, the German ship had ceased firing and the British ships closed to 5,000 yards (4,600 m) to see if she would surrender. One last gun fired, and Leipzig did not strike her colours so the British fired several additional salvos at 19:25. The German captain had mustered his surviving crewmen on deck preparatory to abandoning ship, but the ship's flag could not be reached because it was surrounded by flames, and the British shells wrought havoc on the assembled crew. Leipzig fired two green flares at 20:12 and the British ships closed to within 500 yards (460 m) and lowered boats to rescue the Germans at 20:45. Their ship capsized at 21:32 but only a total of 18 men were rescued in the darkness. Leipzig had hit Glasgow twice, killing a single man and wounding four. The two ships returned to Port Stanley as Cornwall had exhausted her ammunition.[24]

Battle of Más a Tierra

Sturdee's ships continued to search for Dresden even after he returned to England. The German cruiser successfully evaded the searching British for months by hiding in the maze of bays and channels surrounding Tierra del Fuego. She began moving up the Chilean coast in February 1915 until she was unexpectedly spotted by Kent on 8 March when a fog burned off. The British cruiser tried to close the distance, but Dresden managed to break contact after a five-hour chase. Kent, however, intercepted a message during the pursuit from Dresden to one of her colliers to meet her at Robinson Crusoe Island in the Juan Fernández Islands. Dresden arrived there the next day, virtually out of coal.[25]

International law allowed the German ship a stay of 24 hours before she would have to leave or be interned; her captain claimed that his engines were disabled which extended the deadline to eight days. In the meantime, Kent had summoned Glasgow and the two ships entered Cumberland Bay in the island on the morning of 14 March and found Dresden at anchor. The German ship trained her guns on the British ships and Glasgow opened fire, Luce justifying his action by deeming it an unfriendly act by an interned ship that had frequently violated Chilean neutrality. Dresden hoisted a white flag four minutes later as she was already on fire and holed at her waterline. A boat brought Lieutenant Wilhelm Canaris to Glasgow to complain that his ship was under Chilean protection. Luce told him that the question of neutrality could be settled by diplomats and that he would destroy the German ship unless she surrendered. By the time that Canaris returned to Dresden, her crew had finished preparations for scuttling and abandoned ship after opening her Kingston valves. It took 20 minutes before the cruiser capsized to port and sank. The British shells had killed one midshipman and eight sailors and wounded three officers and twelve ratings.[26] After the sinking, a sailor from Glasgow noticed a pig swimming in the water and, after nearly being drowned by the frightened pig, succeeded in rescuing him. The crew named him 'Tirpitz', and he served as the ship's mascot for a year and was then transferred to Whale Island Gunnery School, Portsmouth, for the rest of his life.[27]

Subsequent activities

After re-coaling at Vallenar, Glasgow moved to the Atlantic coast of South America and searched for German ships, mostly around the estuary of the River Plate. On 9 October she departed for Simon's Town, South Africa, to begin a refit and arrived there on the 20th. The refit was completed on 24 December and the ship departed that day for the Abrolhos Rocks where she arrived on 11 January 1916. Glasgow then cruised to São Vicente, Cape Verde, where Luce was promoted to Commodore, 2nd Class on the 29th. Three days later, the ship set sail for the South American coast where she resumed patrolling for German ships. On 14 October, Glasgow arrived back in Simon's Town for another refit that was completed on 27 December, after which the ship returned to South America after a diversion to Sierra Leone.[14] Commodore Aubrey Smith relieved Luce on 8 November.[13]

When Glasgow arrived at Abrolhos Rocks on 22 January 1917, Smith had to coordinate the search for the commerce raider SMS Möwe that was ultimately unsuccessful, with his own ship patrolling off the Brazilian coast.[28] At the beginning of January 1918, the ship was en route to Sierra Leone, where she arrived on the 16th. Departing four days later, the ship reached Gibraltar on 30 January and continued onwards to Portsmouth where she began a refit on 18 February.[14] By July Glasgow was assigned to the 8th Light Cruiser Squadron in the Adriatic Sea.[29] On 2 October the ship covered the bombardment of Durazzo, Albania, by Allied forces.[30]

By April 1919, Glasgow was en route home,[31] but the ship had been paid off at Gibraltar by 1 May.[32] By 1 July, she had been recommissioned and was en route to Britain again.[33] By 18 July, the ship had been reduced to reserve in Portsmouth[34] and she was paid off there on 2 February 1920.[35] Glasgow served as a stokers' training ship in 1922–1926[11] before she was sold for scrap on 29 April 1927 to Thos. W. Ward, of Morecambe.[36]

In 1964 a Falklands Islands commemorative stamp incorrectly pictured Glasgow instead of HMS Kent.[37]

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Lyon, Part 1, p. 56

- ^ a b c d Gardiner & Gray, p. 51

- ^ Lyon, Part 2, pp. 59–60

- ^ Friedman 2010, p. 383

- ^ Lyon, Part 2, pp. 55–57

- ^ Lyon, Part 1, p. 53

- ^ a b Brown, p. 63

- ^ Lyon, Part 2, p. 59

- ^ Lyon, Part 2, p. 57

- ^ Colledge & Warlow, pp. 141–142

- ^ a b c Morris, p. 122

- ^ Friedman 2010, p. 411

- ^ a b c "H.M.S. Glasgow (1909)". www.dreadnoughtproject.org. The Dreadnought Project. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Transcript

- ^ Fayle, pp. 154, 165, 170

- ^ Massie, pp. 221–224

- ^ Massie, pp. 223–228

- ^ Massie, pp. 228–230

- ^ Massie, pp. 232–233, 236

- ^ Massie, pp. 242–243

- ^ Massie, pp. 249–250

- ^ Massie, pp. 251, 258–259, 261

- ^ Massie, pp. 262, 264–265

- ^ Massie, pp. 274–277

- ^ Massie, pp. 283–284

- ^ Massie, pp. 284–285

- ^ Mount, Colin. "Pig in the Post". Royal Philatelic Society London. Archived from the original on 27 June 2011.

- ^ Newbolt, pp. 187–189, 191

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. July 1918. p. 23. Retrieved 4 June 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Cernuschi & O'Hara, p. 69

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. April 1919. p. 21. Retrieved 4 June 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. 1 May 1919. p. 21. Retrieved 4 June 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. 1 July 1919. p. 19. Retrieved 4 June 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. 18 July 1919. p. 707. Retrieved 4 June 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. 18 December 1920. p. 780. Retrieved 4 June 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Lyon, Part 3, p. 51

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth II rarities". Stamp Magazine. 4 October 2006. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

Bibliography

- Brown, David K. (2010). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-085-7.

- Cernuschi, Enrico & O'Hara, Vincent (2016). "The Naval War in the Adriatic, Part 2: 1917–1918". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2016. London: Conway. pp. 62–75. ISBN 978-1-84486-326-6.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Fayle, C. Earnest (1920). Seaborne Trade. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. I: The Cruiser Period. London: John Murray. OCLC 223720130.

- Friedman, Norman (2010). British Cruisers: Two World Wars and After. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-59114-078-8.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Lyon, David (1977). "The First Town Class 1908–31: Part 1". Warship. 1 (1). London: Conway Maritime Press: 48–58. ISBN 0-85177-132-7.

- Lyon, David (1977). "The First Town Class 1908–31: Part 2". Warship. 1 (2). London: Conway Maritime Press: 54–61. ISBN 0-85177-132-7.

- Lyon, David (1977). "The First Town Class 1908–31: Part 3". Warship. 1 (3). London: Conway Maritime Press: 46–51. ISBN 0-85177-132-7.

- Massie, Robert K. (2004). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-04092-8.

- Morris, Douglas (1987). Cruisers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies Since 1879. Liskeard, UK: Maritime Books. ISBN 0-907771-35-1.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. IV (reprint of the 1928 ed.). Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-253-5.

- "Transcript: HMS Glasgow – March 1914 to December 1916, January to February 1918, South America, Battle of Coronel, Battle of the Falklands, South America continued". Royal Navy Log Books of the World War 1 Era. Naval-History.net. Retrieved 30 May 2019.