Gwalior State

State of Gwalior | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1731–1948 | |||||||||||||

Gwalior State within the Maratha Confederacy in 1761 (Yellow) | |||||||||||||

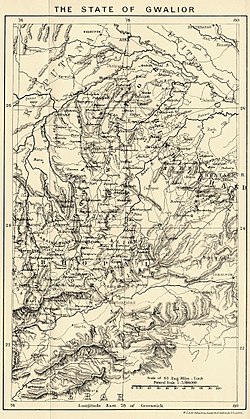

Map of Gwalior State in 1903 | |||||||||||||

| Status | State Within the Maratha Confederacy (1731–1818) Protectorate of the East India Company (1818–1857) Princely State of the India (1857–1947) State of the Dominion of India (1947–1948) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||||||

• 1731–1745 | Ranoji Scindia (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1925–1948 | Jiwajirao Scindia (last) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 1731 | ||||||||||||

| 15 June 1948 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | India ∟ Madhya Pradesh | ||||||||||||

The Gwalior State was a state within the Maratha Confederacy located in Central India. It was ruled by the House of Scindia (anglicized from Sendrak), a Hindu Maratha dynasty. Following the dissolution of the Confederacy, it became part of the Central India Agency of the Indian Empire under British protection.

The state was entitled to a 21-gun salute when it became a princely state of the India.[1] It took its (later) name from the old town of Gwalior, which, although not its first capital, was an important place because of its strategic location and the strength of its fort; it became later its capital, after Daulat Rao Sindhia built its palace in the village of Lashkar, near the fort. The state was founded in the early 18th century by Ranoji Sindhia, as part of the Maratha Confederacy. The administration of Ujjain was assigned by Peshwa Bajirao I to his faithful commander Ranoji Shinde and his Sarsenapati was Yasaji Rambhaji (Rege). The Mahakaaleshwara temple situated in ujjain was reconstructed during the administration of Shrimant Ranojirao Scindia in ujjain.[2][full citation needed]

Under Mahadji Sindhia (1761–1794) Gwalior State became a leading power in Central India, and dominated the affairs of the confederacy. The Anglo-Maratha Wars brought Gwalior State under British suzerainty, so that it became a princely state of the Indian Empire. Gwalior was the largest state in the Central India Agency, under the political supervision of a Resident at Gwalior. In 1936, the Gwalior residency was separated from the Central India Agency, and made answerable directly to the Governor-General of India. After Indian Independence in 1947, the Scindia rulers acceded to the new Union of India, and Gwalior state was absorbed into the new Indian state of Madhya Bharat.[3]

Geography

The state had a total area of 64,856 km2 (25,041 sq mi), and was composed of several detached portions, but was roughly divided into two, the Gwalior or Northern section, and the Malwa section. The northern section consisted of a compact block of territory with an area of 44,082 km2 (17,020 sq mi), lying between 24º 10' and 26º 52' N. and 74º 38' and 79º 8' E. It was bounded on the north, northeast, and northwest by the Chambal River, which separated it from the native states of Dholpur, Karauli, and Jaipur in the Rajputana Agency; on the east by the British districts of Jalaun and Jhansi in the United Provinces, and by Saugor District in the Central Provinces; on the south by the states of Bhopal, Khilchipur, and Rajgarh, and by the Sironj pargana of Tonk State; and on the west by the states of Jhalawar, Tonk, and Kotah in the Rajputana Agency.[4]

The Malwa section, which included the city of Ujjain, had an area of 20,774 km2 (8,021 sq mi). It was made up of several detached districts, between which portions of other states were interposed, and which were themselves intermingled in bewildering intricacy.

In 1940, Gwalior State had 4,006,159 inhabitants.[5]

History

The predecessor state of Gwalior was founded in the 10th century. In 1231 Iltutmish captured Gwalior and from then till 1398 it was a part of Delhi Sultanate.

In 1398, Gwalior came under the control of the Tomars. The most distinguished of the Tomar rulers was Man Singh Tomar, who commissioned several monuments within the Gwalior fort.[6]

It came under the Mughals in 1528 and was a part of the empire till 1731.

The founder of the ruling house of Gwalior was Ranoji Sindhia, who belonged to the Shinde or Sindhia house which traced its descent from a family of which one branch held the hereditary post of patil in Kanherkhed, a village 16 miles (26 km) east of Satara.

In 1726, Ranoji along with Malhar Rao Holkar, the founder of the ruling house of Indore, and the Pawars (Dewas Junior & Dewas Senior), were authorized by the Peshwa Baji Rao I to collect chauth (25% of the revenues) and sardeshmukhi (10% over and above the chauth) in the Malwa districts, retaining for his own remuneration half the mokassa (or his remaining 65 percent). Ranoji fixed his headquarters in the ancient city of Ujjain, which ultimately became the capital of the Sindhia dominion, and on 19 July 1745 he died near Shujalpur, where his centotaph stands. He left three legitimate sons, Jayappa, Dattaji, and Jyotiba, and two illegitimate sons, Tukoji and Mahadji. Jayappa succeeded to the territories of Ranoji, but was killed at Nagaur in 1755. He was followed by his son Jankoji Rao Scindia, who was taken prisoner at the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761 and put to death, and Mahadji succeeded.[citation needed]

Rulers

Mahadji Sindhia (1761–1794)

Madhavrao I, Mahadji, and his successor Daulatrao took a leading part in shaping the history of India during their rule. Mahadji returned from the Deccan to Malwa in 1764, and by 1769 reestablished his power there. In 1772 Madhavrao Peshwa died, and in the struggles which ensued Mahadji took an important part, and seized every chance of increasing his power and augmenting his possessions. In 1775 Raghoba Dada Peshwa threw himself on the protection of the British. The reverses which Sindhia's forces met with at the hands of Colonel Goddard after his famous march from Bengal to Gujarat (1778) the fall of Gwalior to Major Popham (1780), and the night attack by Major Camac, opened his eyes to the strength of the new power which had entered the arena of Indian politics. In 1782 the Treaty of Salbai was made with Sindhia, the chief stipulations being that he should withdraw to Ujjain, and the British north of the Yamuna, and that he should negotiate treaties with the other belligerents. The importance of the treaty can scarcely be exaggerated. It made the British arbiters of peace in India and virtually acknowledged their supremacy, while at the same time Sindhia was recognized as an independent chief and not as a vassal of the Peshwa. A resident, Mr. Anderson (who had negotiated the treaty) was at the same time appointed to Sindhia's court.[7] Between 1782 and December 1805 Dholpur State was annexed by Gwalior.[8]

Sindhia took full advantage of the system of neutrality pursued by the British to establish his supremacy over Northern India. In this he was assisted by the genius of Benoît de Boigne, whose influence in consolidating the power of Mahadji Sindhia is seldom estimated at its true value. He was originally from the Duchy of Savoy, a native of Chambéry, who had served under Lord Clare in the famous Irish Brigade at Fontenoy and elsewhere and who after many vicissitudes, including imprisonment by the Turks, reached India and for a time held a commission in the 6th Madras Infantry. After resigning his commission he had proposed to travel overland to Russia, but was prevented by the loss of his possessions and papers, stolen, it appears, at the instigation of Mahadji, who was suspicious of his intentions. De Boigne finally entered Mahadji's service, and by his genius for organization and command in the field, was instrumental in establishing the Maratha supremacy. Commencing with two battalions of infantry, he ultimately increased Sindhia's regular forces to three brigades. With these troops Sindhia became a power in northern India.

In 1785 Sindhia reinstated the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II on his throne at Delhi, receiving in return the title of deputy Vakil-ul-Mutlak or vice-regent of the Empire, that of Vakil-ul-Mutlak being at his request conferred on Peshwa Madhavrao II, his master, as he was pleased to designate him. Many of the principal feudal lords of the empire refused to pay tribute to Sindhia. Sindhia launched an expedition against the Raja of Jaipur, but withdrew after the inconclusive Battle of Lalsot in 1787. On 17 June 1788 Sindhia's armies defeated Ismail Beg, a Mughal noble who resisted the Marathas. The Afghan chief Ghulam Kadir, Ismail Beg's ally, took over Delhi and deposed and blinded the Emperor Shah Alam, placing a puppet on the Delhi throne. Sindhia intervened, taking possession of Delhi on 2 October, restoring Shah Alam to the throne and acting as his protector. Mahadji sent de Boigne to crush the forces of Jaipur at Patan (20 June 1790) and the armies of Marwar at Merta on 10 September 1790. After the peace made with Tipu Sultan in 1792, Sindhia successfully exerted his influence to prevent the completion of a treaty between the British, the Nizam of Hyderabad, and the Peshwa, directed against Tipu. Mahadji Shinde's role was instrumental in establishing Maratha supremacy over North India . De Boigne defeated the forces of Tukaji Holkar at Lakheri on 1 June 1793. Mahadji was now at the zenith of his power, when all his schemes for further aggrandizement were cut short by his sudden death in 1794 at Wanowri near Pune. Mahadji's death was mystery.

Daulatrao Sindhia (1794–1827)

Mahadji left no heir, and was succeeded by Daulat Rao, a grandson of his brother Tukaji, who was scarcely 15 years of age at the time. Daulat Rao saw himself as the chief sovereign in India rather than as a member of the Maratha Confederacy. At this time the death of the young Peshwa, Madhav Rao II (1795), and the troubles which it occasioned, the demise of Tukaji Holkar and the rise of the Yashwantrao Holkar, together with the intrigues of Nana Fadnavis, threw the country into confusion and enabled Sindhia to gain the ascendancy. He also came under the influence of Sarje Rao Ghatke, whose daughter he had married (1798). Urged possibly by this adviser, Daulat Rao aimed at increasing his dominions at all costs, and seized territory from the Maratha Ponwars of Dhar and Dewas. The rising power of Yashwant Rao Holkar of Indore, however, alarmed him. In July 1801, Yashwant Rao appeared before Sindhia's capital of Ujjain, and after defeating some battalions under John Hessing, extorted a large sum from its inhabitants, but did not ravage the town. In October, however, Sarje Rao Ghatke took revenge by sacking Indore, razing it almost to the ground, and practicing every form of atrocity on its inhabitants. From this time dates the gardi-ka-wakt, or 'period of unrest', as it is still called, during which the whole of central India was overrun by the armies of Sindhia and Holkar and their attendant predatory Pindari bands, under Amir Khan and others. De Boigne had retired in 1796; his successor, Pierre Cuillier-Perron, was a man of a very different stamp, whose determined favouritism of French officers, ind defiance of all claims to promotion, produced discontent in the regular corps.

Finally, on 31 December 1802, the Peshwa signed the Treaty of Bassein, by which the British were recognized as the paramount power in India. The continual evasion shown by Sindhia in all attempts at negotiation brought him into conflict with the British, and his power was completely destroyed in both western and northern India by the British victories at Ahmadnagar, Assaye, Asirgarh, and Laswari. His famous brigades were annihilated and his military power irretrievably broken. On 30 December 1803, he signed the Treaty of Surji Anjangaon, by which he was obliged to give up his possessions between the Yamuna and the Ganges, the district of Bharuch, and other lands in the south of his dominions; and soon after by the Treaty of Burhanpur he agreed to maintain a subsidiary force to be paid for out of the revenues of territory ceded by the treaty. By the ninth article of the Treaty of Sarji Anjangaon he was deprived of the fortresses of Gwalior and Gohad. The discontent produced by the last condition almost caused a rupture, and did actually result in the plundering of the Resident's camp and detention of the Resident as a prisoner.

In 1805, under the new policy of Lord Cornwallis, Gohad and Gwalior were restored, and the Chambal River was made the northern boundary of the state, while certain claims on Rajput states were abolished, the British government at the same time binding itself to enter into no treaties with Udaipur, Jodhpur, Kotah, or any chief tributary to Sindhia in Malwa, Mewar, or Marwar. In 1811, Daulat Rao annexed the neighboring kingdom of Chanderi. In 1816 Sindhia was called on to assist in the suppression of the Pindaris. For some time it was doubtful what line he would take, but he ultimately signed the Treaty of Gwalior in 1817 by which he promised full cooperation. He did not, however, act up to his professions, and connived at the retention of the fort of Asirgarh, which had been ceded by the treaty. In 1818, after the Third Anglo-Maratha War, the rule of the Peshwa was formally ended. A fresh treaty effected a readjustment of boundaries, Ajmer and other lands being ceded.[9]

Jankojirao II Sindhia (1827–1843)

In 1827 Daulat Rao died, leaving no son or adopted heir. His widow, Baiza Bai, adopted Mukut Rao, a boy of eleven belonging to a distant but legitimate branch of the family, who succeeded as Jankojirao Sindhia. Jankojirao was a weak ruler and feuds were constant at his court, while the army was in a chronic state of mutiny. Upon his succession, difficulties arose as to whether the Bai should ruler in her own right or as regent, and her behaviour towards the young king finally caused a rise in feeling in his favour which impelled the Bai to take refuge in British territory. She returned after an interval and lived at Gwalior until her death in 1862. The chief's maternal uncle, known as Mama Sahib, had meanwhile become minister. The most important event during this period was the readjustment of the terms for maintaining the contingent force raised under the treaty of 1817.[10]

Jayajirao Sindhia (1843–1886)

Jankojirao died in 1843; and in the absence of an heir, his widow Tara Bai adopted Bhagirath Rao, a son of Hanwant Rao, commonly called Babaji Sindhia. He succeeded under the name of Jayajirao Sindhia, the Mama Sahib being chosen as regent. Tara Bai, however, came under the influence of Dada Khasgiwala, the comptroller of her household, an unscrupulous adventurer who wished to get all power into his own hands. A complicated series of intrigues followed, which it is impossible to unravel. The Dada, however, succeeded in driving Mama Sahib from the state and became minister. He filled all appointments with his relatives, and matters rapidly passed from bad to worse, ending in the assemblage of large bodies of troops who threatened an attack on Sironj, where Mama Sahib was then residing. War was impending in the Punjab, and, as it was essential to secure peace, the British Government decided to interfere. Colonel Sleeman, the Resident, was withdrawn, and the surrender of Dada Khasgiwala was demanded.[11]

A British force under Sir Hugh Gough moved on Gwalior, and crossed the Chambal in December 1843. On 29 December followed the simultaneous Battles of Maharajpur and Panniar, in which the Gwalior army was annihilated. A treaty was then made, under which certain lands to the value of 1.8 million, including Chanderi District, were ceded for the upkeep of a contingent force, besides other lands for the liquidation of the expenses incurred in the late war, the State army was reduced, and a Council of Regency was appointed during the minority, to act under the residents advice.

In 1852 Dinkar Rao became minister, and under his able management radical reforms were introduced into every department of the administration. Srimant Maharaja Jayajirao (also called as Maharaj Jayajirao saheb Shinde) was in favor to have a fight with British army. On 17 June 1858 Gwalior was captured by Sir Hugh Rose and Maharaja Sri Jayajirao was reinstated. For his services lands worth 300,000 per year, including the portion of Chanderi District west of the Betwa River, were granted to him and he was allowed to increase his infantry from 3000 to 5000 men, and his artillery from 32 to 36 guns. In 1858 Gwalior annexed Chanderi State.[8]

Development in Gwalior State

Jayajirao Shinde was the founder of Development in Gwalior after 1857 and worked for the people of Gwalior to establish their own businesses. He was a very good artist of Gwalior Gharana classical music and opened a school for learning music. The Gwalior got its music in his regein.[check spelling] GCB – Knight Grand Cross Order of the Bath (medal 1.1.1877), GCSI – (25.6.1861), CIE (1.1.1878). In 1872 the state lent 7.5 million for the construction of the Agra-Gwalior portion of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway, and a similar amount in 1873 for the Indore-Nimach section of the Rajputana-Malwa railway.[citation needed] A personal salute of 21 guns was conferred in 1877,[a] and Jayajirao became a Counsellor of the Empress and later on a GCB and CIE. In 1882 land was ceded by the state for the Midland section of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway.

In 1885 Gwalior fort and Morar cantonment, with some other villages, which had been held by British troops since 1858, were exchanged for Jhansi city.[13]

Madhavrao II Sindhia (1886–1925)

Jayaji Rao died in 1886 and was succeeded by his son, Madho Rao Sindhia, then a boy in his tenth year. A council of Regency conducted the administration until 1894, when the Maharaja obtained powers. He took a deep and active interest in the administration of the state, and had a comprehensive grasp of the work done in each department. In 1900 the Maharaja went to China during the Boxer Rebellion, at the same time presenting a hospital ship for the accommodation of the wounded.

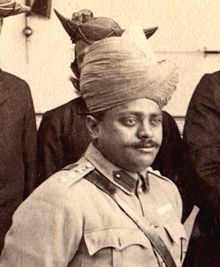

Jivajirao Sindhia (1925–1948)

Jivajirao Sindhia ruled the state of Gwalior as absolute monarch until shortly after India's independence on 15 August 1947. The rulers of Indian princely states had the choice of acceding to either of the two dominions (India and Pakistan) created by the India Independence Act 1947 or remaining outside them. Jivajirao signed a covenant with the rulers of the adjoining princely states that united their several states to form a new state within the union of India known as Madhya Bharat. This new covenanted state was to be governed by a council headed by a ruler to be known as the Rajpramukh. Madhya Bharat signed a fresh Instrument of Accession with the Indian dominion effective from 13 September 1948.[14] Jivajirao became the first rajpramukh, or appointed governor, of the state on 28 May 1948. He served as Rajpramukh until 31 October 1956, when the state was merged into Madhya Pradesh.

Scindia Maharajas of Gwalior

The rulers of Gwalior bore the title of Maharaja Scindia.[8] The Gwalior State Darbar (Court) was composed of many nobles like Jagirdars, Sardars, Istamuradars, Mankaris, Thakurs and Zamindars.[15][16]

Reigning Maharajas

- Ranoji Scindia, Maharaja (1731–1745)

- Jayappaji Rao Scindia, Maharaja (1745–1755)

- Dattaji Scindia, Regent (1755–1760)

- Jankoji Rao Scindia, Maharaja (1755–1761)

- Kadarji Rao Scindia, Maharaja (1763–1764)

- Manaji Rao Scindia, Maharaja (1764–1768)

- Mahadaji Shinde, Maharaja (1768–1794)

- Daulat Rao Sindhia, Maharaja (1794–1827)

- Baiza Bai, Regent (f) (1827–1832)

- Jankoji Rao Scindia II, Maharaja (1827–1843)

- Tara Bai, Regent (f) (1843–1844)

- Jayajirao Scindia, Maharaja (1843–1886)

- Sakhya Bai, Regent (f) (1886–1894)

- Madho Rao Scindia, Maharaja (1886–1925)

- Chinku Bai, Regent (f) (1925–1931)

- Gajra Rajebai, Regent (f) (1931–1936)

- Jiwajirao Scindia, Maharaja (1925–1948)

Titular Maharajas since Union

- Jiwajirao Scindia, (1948–1961)

- Madhavrao Scindia, (1961–2001)

- Jyotiraditya Scindia, (2001–present)

Administration

The revenue of the state in 1901 was Rs. 150,00,000.[17]

For administrative purposes the state was divided into two prants or divisions; Northern Gwalior and Malwa. Northern Gwalior comprised seven zilas or districts: Gwalior Gird, Bhind, Sheopur, Tanwarghar, Isagarh, Bhilsa, and Narwar. The Malwa Prant comprises four zilas, Ujjain, Mandsaur, Shajapur, and Amjhera. The zilas were subdivided into parganas, the villages in a pargana being grouped into circles, each under a patwari.

The administration of the state was controlled by the Maharaja, assisted by the Sadr Board. This Board consisted of seven members, the Maharaja himself being president and the members being in charge of different departments, of which the most important were the Revenue, Land Records and Settlement, Forest, Accounts, Public Works, Customs, and Post Office. The Maharaja had no minister, but a staff of secretaries, supervised by a chief secretary, prepared cases for the final orders of the Maharaja. The zilas were overseen by subahs, or district magistrates; in Northern Gwalior, the subahs answered directly to the Sadr Board, while in Malwa, a Sar Subah was in general charge of the Malwa prant, and controlled and oversaw the work of the four Malwa subahs.

The numerous feudal estates under Gwalior were administered by the local rulers, and were outside the administration of the zilas and prants. The small estates (thakurs or diwans) of Sangul Wardha'Agra ' were nominally under the authority of Gwalior state, but the British Resident had certain administrative and judicial powers.

See also

- Political integration of India

- List of Maratha dynasties and states

- Scindia dynasty under the Maratha empire

- List of Indian princely states

- Rane Khan

- 84 (Scindia) Field Battery

- 74 (Gwalior) Battery

References

- ^ "Gwalior – Princely State (21 gun salute)". Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Website of Shri Mahakaleshwar temple, Ujjain

- ^ Boland-Crewe, Tara; Lea, David (2004). The Territories and States of India. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780203402900.

- ^ Great Britain India Office. The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908.

- ^ Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer, p. 740

- ^ Paul E. Schellinger & Robert M. Salkin 1994, p. 312.

- ^ Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815-1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 157, 171. ISBN 9781576079256.

- ^ a b c Princely States of India

- ^ Ramusack, Barbara N. (2004). The Indian Princes and their States. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139449083.

- ^ Keen, Caroline (2012). Princely India and the British: Political Development and the Operation of Empire. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781848858787.

- ^ Malgonkar, Manohar (1987). Scindia, Vijaya R. (ed.). The Last Maharani of Gwalior: An Autobiography. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780887066597.

- ^ Kwarteng, Kwasi (2011). Ghosts of Empire: Britain's Legacies in the Modern World. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9781408822906.

- ^ Markovits, Claude (ed.) (2004). A History of Modern India: 1480-1950. Anthem Press, London.

- ^ Madhya Bharat- Execution of Instrument of Accession signed by Maharajadhiraja Sir George Jivaji Rao Scindia Bahadur, Raj Pramukh of Madhya Bharat State on 19.7.1948 and its acceptance by Governor General of India on 13.09.1948. New Delhi: Ministry of States, Government of India. 1948. p. 2. Retrieved 2 January 2024 – via National Archives of India.

- ^ Madan, T.N. (1988). Way of Life: King, Householder, Renouncer : Essays in Honour of Louis Dumont. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 129. ISBN 9788120805279. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Russell, Robert Vane (1916). "Pt. II. Descriptive articles on the principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces".

- ^ "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 12, page 433 -- Imperial Gazetteer of India -- Digital South Asia Library".

Notes

- ^ The five largest princely states in British India were Hyderabad, Kashmir, Mysore, Gwalior and Baroda. The rulers of these were entitled to the 21-gun salute. Wavell, who was Viceroy from 1943 to 1947 and was entitled to a 31-gun salute because of his position, reminded himself of these 21-gun states with the mnemonic of "Hot kippers make good breakfast".[12]

Sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gwalior". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin, eds. (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Vol. 5. Routledge/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1884964046.

Further reading

- Breckenridge, Carol Appadurai (1995). Consuming Modernity: Public Culture in a South Asian World. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781452900315.

- Farooqui, Amar (2011). Sindias and the Raj: Princely Gwalior C. 1800-1850. Primus Books. ISBN 9789380607085.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (1999). The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics: 1925 to the 1990s (Reprinted ed.). Penguin Books India. ISBN 9780140246025.

- Major, Andrea (2010). Sovereignty and Social Reform in India: British Colonialism and the Campaign against Sati, 1830-1860. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203841785.

- McClenaghan, Tony (1996). Indian Princely Medals: A Record of the Orders, Decorations, and Medals of the Indian Princely States. Lancer Publishers. pp. 131–132. ISBN 9781897829196.

- Pati, Biswamoy, ed. (2000). Issues in Modern Indian History: For Sumit Sarkar. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 9788171546589.

- Neelesh Ishwarchandra Karkare (2014). Shreenath Madhavji : Mahayoddha Mahadji Ki Shourya Gatha. Neelesh Ishwarchandra (Gwalior). ISBN 9789352670925.

- Neelesh Ishwarchandra Karkare (2017). Tawaareekh-E-ShindeShahi. Neelesh Ishwarchandra (Gwalior). ISBN 9789352672417.