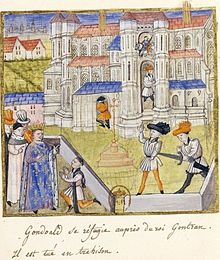

Gundoald

Gundoald or Gundovald was a Merovingian usurper king in the area of southern Gaul in either 584 or 585. He claimed to be an illegitimate son of Chlothar I[1] and, with the financial support of the Emperor Maurice,[2] took some major cities in southern Gaul, such as Poitiers and Toulouse, which belonged to Guntram, king of Burgundy, a legitimate son of Chlothar I. Guntram marched against him, calling him nothing more than a miller's son and named him 'Ballomer'. Gundovald fled to Comminges and Guntram's army set down to besiege the citadel (now known as Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges). The siege was successful, Gundovald's support drained away quickly and he was handed over by the besieged to be executed.

The sources for Gundovald are Gregory of Tours, who wrote about the events in his 'Histories', books 6 and 7 and Fredegar IV.2. Gundoald was never king of Aquitaine as is sometimes thought; there was no such separate kingdom at the time. While his main backers were magnates of Austrasia, the Byzantine support consisted of treasure to buy followers and it is probable that Gundovald spent time in Constantinople before setting off to conquer parts of Gaul.

The usage of 'ballomer', a Frankish (possibly offensive) word of which the meaning is not known, is one of the first instances of the mentioning of a Germanic word in a literary source.

Early life

Gundovald was born in Gaul. According to Gregory of Tours, he was educated with great care and wore his hair long in the style of the Frankish kings, At some point, his mother presented him to Childebert I claiming that his father, Chlothar I, hated him. Childebert I had no sons of his own, so he took Gundovald as his own. In response, Chlothar I demanded that Gundovald be presented to him. Chlothar I claimed that Gundovald was not his son. After Chlothar I's death, Charibert I received Gundovald. However, he was again summoned by Sigebert I who denied his legitimacy once more and cut his hair off. Gundovald was sent to Cologne. Despite his rejection by two Merovingian kings, there is good reason to believe that Gundovald was a genuine offspring of Chlothar I. For a start, he was treated as a royal by two family members.[3] Furthermore, his upbringing was that of a member of royalty. Gregory of Tours himself may have believed he was a child of Chlothar I due to the fact that during his narrative he mentions that Radegund of Poitiers and Ingitrude of Tours can attest to Gundovald's legitimacy. Gregory thought of the former as a saint and thought highly of the latter while composing book seven of the histories, so he likely would have believed their word about Gundovald.[4]

After escaping Cologne, Gundovald went to Italy, where he was received by the Eastern Roman general Narses.The general might have wanted to establish him as governor of the Frankish provinces in Italy; Liguria, Venetia and the Cottian Alps. Installed there, Gundovald could have possibly rallied the local inhabitants to fight off the Lombard invasions.[5] Narses' plans for Gundovald did not come to fruition as he fell from grace and was replaced by Longinus. Nevertheless during his time in Italy, Gundovald married and had children, before moving to Constantinople, where he stayed until his return to Gaul.

The Gundovald Affair

The reason for Gundovald's return to Gaul is not clear. Gundovald himself claims in the Histories that he was invited back by the Austrasian magnate Guntram Boso, who travelled to Constantinople. However, Guntram Boso himself denied this when confronted by Guntram of Burgundy and suggested Duke Mummolus had invited him back. Regardless, upon his return to Gaul, he was received in Marseilles by Bishop Theodore and subsequently he set off to join Duke Mummolus at Avignon. However, Gundovald was soon forced to flee to an island in the Mediterranean after Guntram Boso arrested Bishop Theodore for introducing a foreigner to Gaul. The Bishop Epiphanius was also implicated in the alleged plot to invite Gundovald back, as he arrived in Marseilles at the same time as him.

Gundovald later returned to Gaul again and stayed with Mummolus in Avignon. Accompanied by the Duke and also another called Desiderius, Gundovald soon set off to the district of Limoges, where he was raised up as king on a shield at the tomb of Saint Martin. Gregory writes, as he was carried round the tomb for third time, he stumbled and struggled to stay upright. Following on from these events, Gundovald made a progress through the neighbouring cities. He then planned to move to Poitiers, but was reluctant to do so because he heard an army was being raised against him. Gundovald also asked for an oath of allegiance to Childebert II, his supposed nephew, in all the territories that had previously belonged to Sigibert I. This reinforces the idea that an Austrasian faction was behind Gundovald's return and revolt. Gundovald also demanded an oath of allegiance to himself in all the territories that had belonged to Chilperic I and Guntram of Burgundy. He then moved on to Angoulême, where he received the oath there and gave bribes to its chief citizens. Then Gundovald moved to Périgueux, where he persecuted the Bishop for not having received him with due honour. Next, he marched on Toulouse and sent messengers to its Bishop Magnulf, but the inhabitants of the city prepared to resist the supposed pretender. However, when they saw the size of Gundovald's army, they opened the gates and let his forces in. After the discussions with the Bishop went wrong, Magnulf was prodded with spears, punched, kicked, tied up with rope and banished from his own city

Gundovald then moved on from Toulouse and was pursued by an army made up of the inhabitants of Tours and Poitevins. He decided to go Bordeaux, where he tried to take a finger bone of Saint Sergius to aid his cause. The bone was broken in the process. The revolt subsequently established a new Bishop of Dax and nullified some of Chilperic's decrees. Gundovald soon sent two messengers to Guntram demanding the portion of Chlothar I's realm that was rightfully his. Guntram stretched the messengers, until they admitted that Gundovald had been asked to accept kingship by Childebert II's leaders. As a result of this, Guntram warned Childebert II not to trust his advisers, before accepting him as his heir.

The Siege of Comminges

With Guntram's army approaching, Gundovald soon crossed the Garonne and made for Comminges or Convenae in the foothills of the Pyrenees. The town itself was defended by a 674 metre perimeter wall, so Gundovald decided to make his stand here. When he arrived in Comminges, Gundovald claimed that he had been invited by all those who dwell in Childebert II's realm and ordered the inhabitants to bring food and supplies inside the wall. Furthermore, he told them to hold out for reinforcements. Gundovald also told the men of Convenae to sally forth and fight, but when the citizens of the town were out, Gundovald ordered the gates to be shut on them and the seizure of their possessions.

When the siege had begun, Guntram's men tried to undermine the moral of the defenders. Men climbed to the top of the Matacan, the only highpoint within hailing distance to insult Gundovald. They made reference to his nickname ballomer, his painting skills and the cutting of his hair by Chlothar I and Sigibert I. Gundovald went on the ramparts and answered back to the attackers. Meanwhile, the siege engines brought by Guntram's army were proving ineffective, so Leudgisel, who was in charge of the siege, ordered the construction of new ones. The constructed siege machines mainly consisted of battering rams, with the aim of knocking down holes in the walls. As Guntram's men approached the walls they were bombarded by stones, as well as flaming barrels of pitch and fat.

However, not all the defenders believed Comminges could hold. Duke Bladast, who supported Gundovald, tried to escape the city by setting fire to the church-house as a distraction. Guntram's forces were also constructing an agger, a great ramp or mound- opposite the east wall. With this in mind, the besiegers soon sent messengers to Duke Mummolus and asked him to acknowledge Guntram as his true overlord. Together with Bishop Sagittarius and other supporters of Gundovald, Mummolus went to the cathedral, where they all took an oath to hand over Gundovald to his enemies. When the group confronted Gundovald, they suggested that he should try and make peace with Guntram. According to Gregory, Gundovald knew he was being betrayed. Regardless, he left Comminges anyway. Now outside of the town, Ullo, a man of Guntram, pushed Gundovald over and thrust a lance at him. Gundovald survived, but Boso, one of Guntram's men, threw a stone at him. The stone hit Gundovald in the head and killed him. The next day the gates of the town were opened and Guntram's men slaughtered all the common people, while all the buildings, including churches, were put to the flame and destroyed. Nevertheless, Gundovald was dead and his revolt was over.

References

- ^ Alfons Dopsch, The Economic and Social Foundations of European Civilization, (Routledge, 2006), 199.

- ^ J.B. Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene, Vol. II, (Adamant Media Corp., 2000), 162.

- ^ Bachrach, Bernard S. (1994). The Anatomy of a Little War:: A Diplomatic and Military History of the Gundovald Affair: 568-586. Boulder: Westview Press. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Wood, Ian (1993). "The secret histories of Gregory of Tours". Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire. 71 (2): 253–270. doi:10.3406/rbph.1993.3879.

- ^ Bachrach, Bernard S. (1994). The Anatomy of a Little War:: A Diplomatic and Military History of the Gundovald Affair: 568-586. Boulder: Westview Press. p. 18.

Further reading

- Bachrach, Bernard S. The Anatomy of a Little War: A Diplomatic and Military History of the Gundovald Affair (568–586). Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994.

- Goffart, Walter. "Byzantine policy in the West under Tiberius II and Maurice: the pretenders Hermenegild and Gundovald (579–585)." Traditio 13 (1957): 73-118

- Goffart, Walter. "The Frankish Pretender Gundovald, 582–585. A Crisis of Merovingian Blood." Francia 39 (2012): 1-27.

- Gregory of Tours decem libri historianum.