Basuto Gun War

| Basuto Gun War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the South African Wars (1879-1915) | |||||||

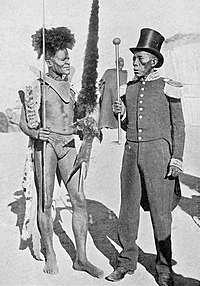

Masopha with his standard bearer | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Basuto |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lerotholi Masopha |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 23,000 |

4,000 three mountain guns two mortars | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown |

94 killed 112 wounded | ||||||

The Basuto Gun War, also known as the Basutoland Rebellion, was a conflict between the Basuto and the British Cape Colony. It lasted from 13 September 1880 to 29 April 1881 and ended in a Basuto victory.

Following Basutoland's transformation into a British royal dominion on 12 March 1868, it became the target of rapid westernization efforts by the Cape Colony administration. In 1879, the Cape Parliament extended the Peace Preservation Act to Basutoland, with the aim of disarming the Basuto people. The immense significance of guns in Basuto society, compounded with past grievances, resulted in a rebellion led by chiefs Lerotholi and Masopha, which erupted on 13 September 1880. Heavily outnumbered and stretched thin by the simultaneous outbreak of other revolts, the Cape Colonial Forces failed to achieve a decisive military victory.

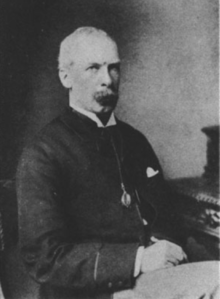

The ensuing military stalemate and the high cost of conducting the war in made it increasingly unpopular among Cape politicians. On 29 April 1881, High Commissioner for Southern Africa, Sir Hercules Robinson announced the peaceful settlement of the conflict. The Cape's subsequent efforts to enforce disarmament and re-establish the rule of law in Basutoland met with stiff resistance from Masopha and his supporters. Unable to control the Basuto, the Cape Parliament passed the Disannexation Act in September 1883. The Basuto Gun War represents a rare example of an African nation's military victory against a colonial power, whereby the Basuto were able to retain their guns. Under the terms of the Disannexation Act, Basutoland was transformed into a British High Commission Territory, and thus not later incorporated into the Union of South Africa.

Background

During the early 19th century, a diverse group of Sotho-, Nguni- and Tswana-speaking tribes settled in the Caledon River region. The latter two, which formed the minority of the population, were gradually assimilated by the culturally dominant Sotho. King Moshoeshoe I united the various Sotho-speaking chieftainships into a single nation during a period of political turbulence known as Lifaqane. He transformed the denigratory exonym of Sotho into the name of the nascent Basuto nation.[1][2] In 1833, missionaries from the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society began setting their outposts in Basuto lands following Moshoeshoe's invitation. They promoted a combination of Christianity, Western civilization, and commerce. They saw Basuto customs linked to obligatory labor and the dependence of the population on their chiefs as evil. They sought to undermine them by promoting private property, the commodization of production and closer economic ties with European settlers.[3]

In the 1820s, the Basuto faced cattle raids from the Koranna and first encountered horses and guns in a combat setting. They obtained horses and guns of their own, and began stockpiling gunpowder. By 1843, Moshoeshoe had accumulated more horses and guns than any other chieftain in South Africa, but the guns were outdated flintlocks, which had flooded the South African market after the introduction of percussion lock muskets.[4] In 1852, the British signed the Sand River Convention with the Boers, banning the sale of guns to Africans, while continuing to trade between themselves under the terms of the 1854 Bloemfontein Convention. The Boer Orange Free State was able to procure modern breech-loading rifles and a small amount of artillery. The Basuto were forced to rely on smuggled and locally-produced gunpowder, which was of inferior quality.[5]

In 1858, hostilities broke out between the Basuto and the Orange Free State. Inferior in both marksmanship and materiel, the Basuto suffered a series of defeats in wars that lasted until 1868.[5] In 1866, the two sides signed the Treaty of Thaba Bosiu, whereby Moshoeshoe ceded most of his kingdom's arable land to the Boers. Hostilities resumed soon afterwards, and the Boers began employing a scorched earth policy, leading to starvation among the Basuto. The Basuto appealed to British High Commissioner for Southern Africa Sir Philip Wodehouse and the Colony of Natal for protection. Although, initially reluctant to intervene, on 12 March 1868 Wodehouse proclaimed Basutoland to be a royal dominion.[6]

The Basuto, who became part of the British Empire out of necessity, viewed any kind of colonial administration as “a snake in the house”.[7] While the British, saw it as their responsibility to westernize their new subjects.[8] Wodehouse therefore supported a gradual introduction of colonial laws, so as not to provoke backlash from the Basuto.[9] Basutoland's legal status remained unclear, with the Colonial Office at various times calling it a crown colony and a protectorate. Letsie I, who succeeded Moshoeshoe in 1870, viewed the annexation as merely a treaty of alliance and protection. Basuto chiefs therefore actively challenged the efforts of British authorities to enact major reforms without prior consultations.[10] On 31 December 1870, Sir Henry Barkly was appointed as the new High Commissioner for Southern Africa. The British had long entertained the idea of incorporating Basutoland into the Cape Colony, and Barkly immediately pushed for annexation on the premise of the financial costs incurred by the colony's policing of Basutoland. The bill confirming the annexation was approved by the Cape Parliament on 11 August 1871.[11]

Prelude

Morosi's Revolt

The Cape government immediately began to undermine the traditional power structures of the Basuto. Under the terms of the Mercantile Law of 1871, trade was restricted to those in possession of a government license.[9] In 1872, it implemented the responsible government system, under which the governor's legislative powers were transferred to the Cape Parliament. The Basuto were neither consulted nor formally informed. They were also barred from participating in the parliament unless they accepted to completely abandon their traditional laws and customs, a condition they deemed unacceptable. From that point on, Letsie I and the Governor's Agent in Basutoland, Colonel Griffith, became embroiled in a power struggle.[12] The Cape-appointed magistrates were given autonomy in enforcing colonial legislation as they saw fit. The magistrates interfered with land disputes, when the Basuto previously held exclusive rights on land allocation.[13] Authority over marriage disputes and disputes between the Basuto and white residents were likewise transferred to magistrates' courts. Basuto prophetesses claimed to have communicated in their dreams with the spirit of Moshoeshoe, who had become increasingly angry with the white man's interference in Basuto affairs.[14]

The southern corner of Basutoland was settled by the Baphuthi people. Their chief Morosi was once a tributary ruler of Moshoeshoe[15] who had reluctantly merged his territory with British Basutoland in 1869. In 1877, the colonial authorities created the Quthing District and appointed Hamilton Hope as the magistrate to oversee the Baputhi,[16] a move opposed by Morosi.[17] In April 1878, the colonial authorities dispatched 80 African policemen and 700 Basuto warriors to apprehend Morosi's son Doda; the dispute was resolved peacefully. Hope was replaced by the more experienced John Austen, who was likewise distrusted by Morosi.[18] Doda was finally imprisoned after being implicated in horse theft, his subsequent escape from captivity and Morosi's refusal to hand him over impelled Cape Colony prime minister Sir Gordon Sprigg to authorize the forced disarmament of the Baphuthi. Austen ordered Letsie I to assist the Cape in the campaign, threatening to hand over parts of Quthing to white settlers and establish garrisons of colonial troops in Basutoland. Letsie I reluctantly agreed. The fighting lasted for several months, as the Baphuthi had entrenched themselves in the isolated Mount Moorosi. On 28 November 1879, the colonial troops managed to reach the summit with ladders, killing Morosi in the final confrontation. Morosi's severed head was paraded in King William's Town, an act that shocked Letsie I.[16][19]

Opposition to the Peace Preservation Act

In 1878, the Cape Parliament had passed the Peace Preservation Act, which allowed for the confiscation of the firearms of the African population in exchange for a monetary compensation. Sprigg decided that its implementation should extend to the Basuto, after witnessing 7,000 Basuto cavalrymen perform maneuvers during the course of Morosi's uprising.[20] This was announced during a pitso (formal assembly) attended by some 6,000 to 10,000 Basuto. Soon afterwards he also declared that the Quthing region would be confiscated by the Cape for white settlement.[21][22] At the time almost half of all Basuto men owned a firearm.[23] Many had worked in railway construction and the diamond mines in Griqualand West with the express purpose of purchasing modern breech-loading and smoothbore rifles.[24] As a result, the Basuto became the best-armed tribe in southern Africa.[25] For the Basuto gun confiscation was unacceptable, not only due to their high value,[23] but also due to the necessity to defend their land and cattle in an environment where there was no guarantee of protection from the colonial authorities. For the Basuto, guns were a symbol of manhood, and to be disarmed was seen as being reduced to the status of a child.[20] In April 1879, the Cape Colony doubled the hut tax in Basutoland to one £ per hut.[26]

In June 1880, Letsie I dispatched a three-man delegation to the Cape Parliament as it was deliberating the annexation of Quthing and the question of Basuto disarmament. The delegation argued that the annexation was a violation of prior agreements between Moshoeshoe and Wodehouse, while disarmament was unnecessary since the Basuto remained loyal to the Cape. The delegation was not allowed to present its case in the parliament. Petitions from the Basuto and their sympathizers from among the Paris Evangelical Society missionaries followed, all of which failed to produce a favorable result. Letsie I, now old and in declining health, was unwilling to lead an armed revolt, believing it to be futile. Cape Governor Sir Henry Bartle Frere became impatient at the deliberations and ordered Letsie I to enact disarmament immediately, even before the Basuto delegation had returned from Cape Town.[27][28]

Few Basuto complied with the order and handed over their arms. This catalyzed the Cape Parliament to vote in favor of disarmament. The delegation announced their failure to prevent the enactment of the Peace Preservation Act at a pitso convened on 3 July. The heir to the Basuto throne, Lerotholi, spoke against disarmament, while Letsie's brother chief Masopha and his nephew chief Joel Molapo openly challenged the order and advocated for armed resistance. Masopha began to fortify the stronghold of Thaba Bosiu, while the supporters of the rebel chiefs began ignoring orders from the local magistrates. White traders abandoned Basutoland, and Basuto loyalists fled to the magistracies for protection as armed bands roamed freely in the region.[29][30]

Sprigg urged Letsie I to negotiate Masopha's unconditional surrender, until a force of Cape Mounted Riflemen (CMR) could arrive to assist him. Letsie I replied that this was unrealistic, as most of the Basuto, including his sons, had rallied behind Masopha. Letsie and his armed retinue, returned to their village on 19 August after several days of negotiations, fearing that they would be ambushed if they remained outside Thaba Bosiu any longer.[31] In a last ditch effort to prevent an uprising, Sprigg visited Letsie I in person. Letsie I then held another pitso—under Sprigg's new terms the rebel chiefs were to appear in court where they would receive a token fine, pledge to compensate those whose property they had seized, and comply with the gun regulations. Masopha remained defiant and held an assembly of his own, where he and Lerotholi began to prepare for war. Masopha believed that the Cape's troops had proved themselves to be incompetent during the suppression of Morosi's revolt. He was further encouraged by rumors that the British would refuse to reinforce the Cape,[32] and by the British defeat at the Battle of Isandlwana a year prior.[25]

Conflict

September 1880

On 13 September 1880, a 212-man unit of Cape Mounted Riflemen under Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Carrington crossed into Basutoland in the vicinity of Wepener in order to reinforce the isolated magistracy at Mafeteng.[33][34] Upon hearing of Carrington's advance, the Mafeteng District magistrate Arthur Barkly set off with 20 policemen to scout ahead. Some 2 miles (3.2 km) from the magistracy, he encountered 300 Basuto warriors commanded by Lerotholi on a hill range overlooking the road. The two parleyed, and Barkly informed Lerotholi of the column's imminent approach and advised him to surrender his arms and withdraw. Lerotholi refused and rode back to his men, after seeing the CMR appear on the rear of the police force. The Basuto then charged down from the hill, and a short skirmish ensued whereby the Basuto suffered light casualties. Carrington's troops then garrisoned Mafeteng,[35] where they were besieged by Lerotholi.[33] On 17 September, a CMR unit was attacked by 700 Basuto outside Mafeteng. Following this attack Sprigg ordered the mobilization of the Cape's armed forces.[36]

The army mustered by the Cape government for the conflict, consisting entirely of Cape Colonial Forces troops, was commanded by Brigadier General Charles Clarke, who visited the frontlines only twice during the war, relegating his responsibilities to Adjutant General Major W. F. D. Cochrane and Carrington. Carrington was appointed as the Commandant of the Mafeteng Region and entrusted with a force of approximately 2,000 men. Its cavalry included 400 men from the Cape Mounted Riflemen, 600 men from the Cape Mounted Yeomanry (CMY), 200 riders from Kimberley Horse, as well as small units of scouts and African levies. Its infantry consisted of the Prince Alfred Volunteer Guards, Duke of Edinburgh's Volunteer Guards and First City Volunteer Rifles, each numbering 100 to 200 soldiers. The force also included three RML 7-pounder mountain guns and two 5.5-inch mortars.[37] A total of 3,000 white and 1,000 African troops were involved in the campaign.[38]

The Basuto vastly outnumbered their adversaries, Lerotholi commanded 23,000 cavalry, of which 9,000 were concentrated in the Mafeteng District where most of the fighting took place. A part of the Basuto army was tasked with guarding Letsie's ancestral village of Morija.[39] Masopha blockaded the garrison of 200 CMR soldiers at Maseru.[34] He burned Maseru's main buildings in his first assault on the town, but further attacks proved less successful.[40] In the north, Joel Molapo's attack on Hlotse was likewise repulsed and he initiated a siege. The magistracies at Mohale's Hoek and Quthing were abandoned by the Cape troops.[34] The rebellion continued to spread across Basutoland, with clashes taking place across seven different fronts.[25] The heavy casualties suffered by the Basuto during their frontal assaults caused them to increasingly adopt the tactics of the Boer Commando; employing ambushes and defending fortified positions. Their high mobility allowed them to engage their opponents only when they believed that conditions favored them and to quickly withdraw after firing. While the Basuto remained inferior marksmen in comparison to their opponents, the quality and the quantity of the arms at their disposal had increased considerably since the Boer wars.[41][33]

October 1880

The outbreak of the Gun War (also known as Basutoland Rebellion) prompted other tribes to rise up in revolt. In Griqualand East, Charles Brownlee reported that the Basuto clans residing south of Drakensberg had been incited to revolt by the rebels in Basutoland on 4 October. Brownlee initially attempted to quell the uprising through negotiations, however this plan had to be abandoned when the learnt that the rebels were planning to assassinate him and the members of his administration. He then evacuated his district's white population to Kokstad, while the rebels massacred members of the loyalist Hlubi and Bhaca tribes.[42] Members of the Griqua and Mpondomise tribes rose up in the Qumbu and Tsolo Districts. The Qwati and some of the Thembu clans launched their own revolts in Thembuland.[34] While Basuto incitement did play a role, the causes of those rebellions varied. Some tribes feared disarmament, others opposed the continuous erosion of traditional power structures, while others believed that merely by killing the local white population, colonial rule would disappear.[43] The revolts in Transkei lasted until February 1881 and forced the already outnumbered Cape army to divert troops to other fronts.[34]

Frere was recalled to Britain and Major General Henry Hugh Clifford, who had temporarily succeeded him, opposed both the war and Sprigg's policies.[36] Under the terms of the responsible government system, the Cape was responsible for its own internal security, with two British regiments being stationed in the region for the War Office's own purposes.[44] Clifford insisted that no British troops should be committed for the suppression of the rebellion.[45] In October, Clarke arrived at Wepener at the head of a force of 1,000 cavalry, 600 infantry, five artillery pieces, and 40 wagons.[33] Clarke was aiming to relieve Mafeteng, whose garrison was forced to exchange messages written in Greek, since some Basuto chiefs spoke both English and French. Clarke's advance was slowed by deep mud, and the Basuto cavalry regularly harried the column with rifle fire before withdrawing.[46] On 19 October, the Cape army reached Qalabane, an isolated kop halfway between Wepener and Mafeteng. Lerotholi had positioned 3,000 of his warriors behind a ridge that overlooked a nearby road. The advanced guard of the Cape Mounted Yeomanry came under rifle fire from the kop. Clarke ordered the artillery to fire upon the kop and dispatched 200 men from the 1st Cape Mounted Yeomanry to flank the kop from the left. CMY commander Captain Dalgety ordered his soldiers to dismount and assume an open order formation. Chief Seiso's led an charge of 300 axe-wielding Basuto cavalrymen on Dalgety's unit before the latter was able to reach the crest. The 2nd CMY reinforced Dalgety soon afterwards and captured a nearby village.[47] The Cape army lost 32 killed and seven injured,[41] while the Basuto lost 40 killed.[47] The yeomanry was almost defenseless in hand-to-hand combat, as it was not yet issued bayonets or swords.[46] The battle at Qalabane demoralized the Cape Mounted Yeomanry, which had previously successfully repulsed much larger bodies of enemy troops, but the Basuto hailed the clash as a great victory. Clarke reached Mafeteng, engaging in counter-insurgency operations in its vicinity until the end of the month before returning to the Cape.[47]

November 1880 – January 1881

In November, Carrington destroyed villages adjacent to his line of communication and advanced towards Morija. In early December, he set up camp at Tsita's Nek, engaging in multiple clashes with the Basuto on the road to Morija. On 14 January 1881, Colonel Brabant led a force of 380 cavalry, 180 infantry, 400 armed burghers, and two 7-pounder guns towards Thaba Tsueu. Brabant sent the burghers ahead to capture the Radiamari village. After burning Radiamari, the burghers disregarded their orders and pushed further into Sepechele village, which was held by 8,000 men under Lerotholi. Chief Maama charged the burghers with 3,000 of his warriors, and the latter began to withdraw towards the rest of the Cape force. The Basuto managed to close in on the burghers but were eventually beaten off with carbine and artillery fire. As Maama retired, Lerotholi's warriors opened heavy fire from the surrounding ridges. Surgeon John Frederick McCrea of the 1st CMY won the Victoria Cross for attending injured burghers while being wounded himself. Brabant sent 140 riders from the Yeomanry in pursuit of Maama. The initial counter-attack failed after it was outflanked from the right. The Cape troops then dismounted and cleared the plateau and surrounding ridges. The Basuto suffered heavy casualties, while the Cape lost 16 killed and 21 wounded. Brabant then returned to his camp at Tsita's Nek.[48]

For most of the war the Cape's troops and administration remained isolated in the Hlotse, Maseru, and Mafeteng Districts. The lack of offensive action reduced the Cape troops’ morale still further.[49] Letsie I officially remained loyal to the Cape, while tacitly supporting the rebellion by confiscating land from Basuto loyalists and accepting Austen's severed head as a peace offering from Transkeian chief Tlokwa.[34][50] According to Basuto oral tradition, Letsie I purposefully cultivated the image of a weak and unintelligent leader, while covertly communicating with the rebel leaders and encouraging the continuation of the rebellion. Basuto loyalist leaders like Jonathan Molapo surrendered their weapons on Letsie's orders so as to maintain control of the country in case the rebels were defeated. During the course of the war, Griffith continued to believe in Letsie's loyalty, blaming his inability to control his chiefs for the war.[51]

In January the outbreak of the First Boer War put further pressure on the Cape's already limited resources. By that time, the Cape war expenditure had reached £3 million. Fearing that Free State burghers might defect to the South African Republic, Cape authorities refused to allow new Boer volunteers to join the Basutoland campaign. The same month, the Basuto sued for peace with the assistance of opposition parliamentarian Jacobus Wilhelmus Sauer. As the maize harvest season neared, the Basuto began to fear that further fighting would lead to starvation in the following year. Under the terms put forward by the Basuto, they would retain their guns and autonomous rule. The deal was rejected by the Cape government, which demanded the surrender of all guns, the submission of the Basuto to Cape laws, and the leaders of the rebellion to stand trial with the guarantee that they would not be sentenced to death. Negotiations broke down, but the seven-day armistice allowed the Basuto to harvest their crops. The newly appointed High Commissioner for Southern Africa, Sir Hercules Robinson, continued to insist on a peaceful settlement of the conflict.[52]

February–April 1881

On 14 February Carrington captured Ramakhoatsi, which overlooked the main road to Morija. The following day, a force of 370 cavalry, 100 infantry, 50 native levies, and three artillery pieces under Brabant was sent out in search of a new camping ground. Upon crossing a spruit in the Ramibidikwa area, a CMR scout reported a massed formation of Basuto horsemen. Brabant ordered his soldiers to form a square; soon afterwards the Basuto commenced an attack on its front and two flanks. A combination of rifle and case shot fire kept the Basuto at bay in the center and the right flank. On the left, the Basuto managed to almost reach melee range before being likewise driven off. The artillery continued to fire on the retreating Basuto, who suffered 138 casualties in the engagement. One month later Clarke assumed personal command of the force, moving the camp to Ramibidikwa, 20 miles (32 km) from Morija. On 22 March, Carrington was heavily wounded in the vicinity of the new camp. [53]

By early April, Sprigg's conduct of the war was being heavily criticized in the Cape Parliament, whose opposition members were pushing for a vote of no confidence.[54] Using Letsie as an intermediary, Robinson organized a meeting between Griffith and Lerotholi outside Maseru on 17 April. The two sides signed an armistice, although Lerotholi was unwilling to surrender his weapons, as the motion would be too unpopular among his tribesmen. On 29 April, Robinson announced the peace settlement, known as the Award. Under its terms the Basuto would be allowed to keep their guns, provided they officially register them and pay an annual fee of one pound per weapon. The Cape pledged to provide an amnesty for the rebels and allow for Quthing to remain a part of Basutoland. The Basuto agreed to pay a collective fine of 5,000 cattle and compensate Basuto loyalists and white traders. The Award marked the end of the conflict.[55] The Cape's casualties during the war totaled 94 killed and 112 wounded.[38]

Aftermath

Opposition to the Award

Basuto chiefs—including Lerotholi—welcomed the Award, and 3,000 heads of cattle were paid almost immediately as a gesture of goodwill. On 9 May 1881, Thomas Charles Scanlen replaced Sprigg as prime minister, while Basutophile Jacobus Wilhelmus Sauer was appointed as the new Secretary for Native Affairs.[55] Scanlen encountered challenges in fully enforcing the Award, such as the erosion of the colonial administration's prestige.[56] Masopha demanded to be granted almost arbitrary power, refusing to pay his share of the hut tax and forbidding the return of the local magistrate.[57] Joseph Orpen, who replaced Griffith, was seen as too sympathetic to the former rebels. His handling of cattle and land compensation led to the alienation of Basuto loyalists and the departure of nearly all pre-war magistrates from Basutoland.[58] In January 1882, Letsie I assembled an army in order to enforce the Award on Masopha, yet the expedition was cancelled as it was judged that Masopha retained considerable popular support. The Colonial Office refused to allow the Cape to abandon Basutoland and cancel the Award. Robinson then set 15 March as the new deadline for the enforcement of the Award, threatening to confiscate land from the chiefs failing to abide to it and to redistribute Quthing District to white volunteers who fought in the war. Following pleas by Letsie I and Orpen,[59] Robinson cancelled the Award on 15 March and pledged not to confiscate land. This was followed by the repeal of the Peace Preservation Act on 6 April.[60]

The Basuto’s lack of cooperation gave rise to calls for Basutoland's disannexation within the Cape Parliament. Eager to restore pre-war order, Scanlen invited Major General Charles George Gordon to Basutoland. Gordon had built a reputation as a capable administrator and an expert negotiator.[61] He proposed replacing the magisterial system, granting the Basuto chiefs de facto autonomous rule. The proposal was rejected by John X. Merriman as unenforceable, citing the absence of unity among the Basuto.[62] Merriman persuaded Gordon to stay in the Cape for an additional year. Sauer and Gordon then traveled to Basutoland in September 1882, Gordon was convinced that he could resolve the conflict if he were to enter negotiations with Masopha. On 16 September, Sauer held a private meeting with Letsie I and Lerotholi, and consented to the Basuto chiefs' proposal to assemble a force against Masopha.[63] On 25 September, Gordon departed for a meeting with Masopha at Thaba Bosiu, at the same time Lerotholi had completed preparations to launch an assault on the stronghold.[64] During his meeting with Masopha, Gordon disobeyed written instructions given to him by Sauer. Furthermore, Masopha intentionally prolonged the negotiations, thus thwarting Lerotholi's assault on the mountain. Gordon departed Thaba Bosiu without having achieved his objective and resigned soon afterwards. Lerotholi felt humiliated by the incident, which developed into a long-lasting rivalry between him and his uncle.[65]

Disannexation

In the northern Leribe District, rebel chief Joel Molapo and loyalist chief Jonathan Molapo continued to clash sporadically over the Leribe chieftaincy. Joel continuously attacked local loyalists in an effort to seize power, complicating the settlement of the Gun War. The fighting resulted in a wave of refugees fleeing towards the Orange Free State.[66] A month later, a number of Basuto chiefs including Masopha, failed to appear at a pitso called by Orpen's successor Matt Blyth, thus rejecting Scanlen's new proposal for semi-autonomous rule. Aided by Masopha, Joel Molapo continued to massacre and destroy the properties of his opponents. During one of his raids, his warriors burnt the stone house of his deceased father, which shifted popular opinion against him. In May, Letsie I officially granted Jonathan the Leribe chieftaincy, but despite Letsie's declaration, violence in Leribe did not subside until the end of the year. Facing continued diplomatic protests from the Free State and unable to enforce the law in Basutoland, the Cape Parliament passed the Disannexation Act in September 1883.[67]

A pitso held at Maseru on 29 November resulted in most chiefs voting in favor of remaining British subjects. Masopha did not attend the Maseru pitso, holding one of his own; where he demanded complete independence. The British Secretary of State issued an Order-in-Council granting the queen's support to the Disannexation Act, which came into force on 18 March 1884. Under its terms the newly created High Commission Territory of Basutoland was to be indirectly ruled by the Basutoland High Commissioner Marshal Clarke. The Basuto retained their guns, prevented the alienation of their land to white settlement and thwarted the absorption of their country by the Free State, which would have inevitably occurred had they gained complete independence. The Basuto chiefs retained most of their past authority, while unrest in Masopha's district was only brought to an end after his defeat in the 1898 Basuto Civil War.[68] The Basuto Gun War represents a rare example of an African nation's military victory against a colonial power in the 19th century. Its status as a High Commission Territory meant that Basutoland was not incorporated into the Union of South Africa in 1910.[69]

Footnotes

- ^ Rosenberg, Weisfelder & Frisbie-Fulton 2004, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Maliehe 2014, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Atmore & Sanders 1971, pp. 536–537.

- ^ a b Atmore & Sanders 1971, pp. 540–541.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Eldredge 2007, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Burman 1981, p. 17.

- ^ a b Maliehe 2014, p. 31.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 97–101.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, p. 51.

- ^ a b Rosenberg, Weisfelder & Frisbie-Fulton 2004, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Burman 1981, p. 110.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 121–124.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Burman 1981, p. 133.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, p. 52.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Eldredge 2007, p. 71.

- ^ Atmore & Sanders 1971, p. 541.

- ^ a b c Tylden 1936, p. 98.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 139–142.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b c d Tylden 1936, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f Burman 1981, p. 148.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 145–147.

- ^ a b Kotze 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Tylden 1936, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Tylden 1936, p. 104.

- ^ Tylden 1936, p. 99.

- ^ Eldredge 2007, p. 106.

- ^ a b Atmore & Sanders 1971, p. 543.

- ^ Kotze 2012, p. 53.

- ^ Kotze 2012, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Kotze 2012, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Kotze 2012, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Burman 1981, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Tylden 1936, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Tylden 1936, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Kotze 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Machobane & Karschay 1990, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Eldredge 2007, pp. 82–86.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Tylden 1936, pp. 102, 104.

- ^ Burman 1981, p. 151.

- ^ a b Eldredge 2007, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Burman 1981, p. 154.

- ^ Bradlow 1970, p. 224.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Eldredge 2007, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Bradlow 1970, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Bradlow 1970, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Bradlow 1970, pp. 230–233.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Eldredge 2007, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Burman 1981, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Eldredge 2007, pp. 113–116.

- ^ Eldredge 2007, pp. 116–118.

- ^ "Gun War". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

References

- Atmore, Anthony; Sanders, Peter (1971). "Sotho Arms and Ammunition in the Nineteenth Century". The Journal of African History. 12 (4): 535–544. doi:10.1017/S0021853700011130. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 181011. S2CID 161528484 – via JSTOR.

- Bradlow, Edna (1970). "General Gordon in Basutoland". Historia. 15 (4): 223–242. ISSN 0018-229X. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- Burman, Sandra (1981). Chiefdom Politics and Alien Law: Basutoland under Cape Rule 1871–1884. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-04639-3.

- Eldredge, Elizabeth (2007). Power in Colonial Africa: Conflict and Discourse in Lesotho, 1870–1960. The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-22370-0.

- Kotze, J. (2012). "Counter-Insurgency in the Cape Colony, 1872–1882". Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies. 31 (2): 36–58. doi:10.5787/31-2-152. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- Machobane, L. B.; Karschay, Stephan (1990). Government and Change in Lesotho, 1800–1966: A Study of Political Institutions. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-51570-9.

- Maliehe, Sean (2014). "An obscured narrative in the political economy of colonial commerce in Lesotho, 1870–1966". Historia. 59 (2): 28–45. hdl:2263/43121. ISSN 0018-229X. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- Rosenberg, Scott; Weisfelder, Richard; Frisbie-Fulton, Michelle (2004). Historical Dictionary of Lesotho. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4871-6.

- Tylden, G. (1936). "The Basutoland Rebellion of 1880–1881". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 15 (58): 98–107. ISSN 0037-9700. JSTOR 44227993.

Further reading

- Cape Colony House of Assembly (1881). Copies of all Correspondence and Telegrams Having Reference to the Recent Rebellion. Saul Solomon & Co. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Lagden, Godfrey (1910). The Basutos: The Mountaineers & Their Country. Vol. II. Appleton. OCLC 908824713. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Sanders, Peter (2011). Throwing Down White Man: Cape Rule and Misrule in Colonial Lesotho, 1871–1884. Merlin Press. ISBN 978-0-850-36654-9.

- Tylden, G. (1969). "Basutoland Roll of Honour 1851 – 1881". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 1 (5). ISSN 0026-4016. Retrieved 7 January 2022.