Flag of Greece

| |

| Other names | Η Γαλανόλευκη, Η Κυανόλευκη |

|---|---|

| Use | National flag and ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 (and also 7:12) |

| Adopted | 22 December 1978 (Naval Ensign 1822–present, National Flag 1969–70; 1978–present) |

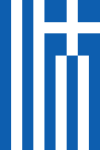

| Design | Nine horizontal stripes, in turn blue and white; a white Greek cross throughout a blue canton. |

The national flag of Greece, popularly referred to as the Blue-and-White (Γαλανόλευκη, Galanólefki) or the Cyan-and-White (Κυανόλευκη, Kyanólefki), is officially recognised by Greece as one of its national symbols and has 5 equal horizontal stripes of blue alternating with white. There is a blue canton in the upper hoist-side corner bearing a white cross; the cross symbolises Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The blazon of the flag is Azure, four bars Argent; on a canton of the field a Greek cross throughout of the second. The official flag ratio is 2:3.[1] The shade of blue used in the flag has varied throughout its history, from light blue to dark blue, the latter being increasingly used since the late 1960s. It was officially adopted by the First National Assembly at Epidaurus on 13 January 1822.

While the nine stripes do not have any official meaning, the most popular interpretation says that they represent the syllables of the phrase Ελευθερία ή Θάνατος ('Freedom or Death'): the five blue stripes for the syllables in Ελευθερία, the four white for those of ή Θάνατος.[2] The total of nine stripes is also said to represent the letters of the word ελευθερία ("freedom").[2] White and blue symbolise the colours of the Greek sky and sea.[3]

Historical background

The origins of today's national flag with its cross-and-stripe pattern are a matter of debate. Every part of it, including the blue and white colors, the cross, as well as the stripe arrangement can be connected to very old historical elements; however, it is difficult to establish "continuity", especially as there is no record of the exact reasoning behind its official adoption in early 1822.[citation needed]

It has been suggested by historians that the current flag derived from an older design, the virtually identical flag of the powerful Cretan Kallergis family. This flag was based on their coat of arms, whose pattern is supposed to be derived from the standards of their claimed ancestor, Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas (963–969 AD). This pattern (according to not easily verifiable descriptions) included nine stripes of alternating blue and white, as well as a cross, assumed to be placed on the upper left.[4] Although the use of alternating blue and white - or silver - stripes on (several centuries-old) Kallergis' coats of arms is well documented, no depiction of the above described pattern (with the nine stripes and the cross) survives.[5]

Antiquity and the Byzantine Empire

Flags as they are known today did not exist in antiquity. Instead, a variety of emblems and symbols (σημεῖον, sēmeîon; pl. σημεῖᾰ, sēmeîa) were used to denote each state and were for example painted on the hoplite shields. The closest analogue to a modern flag were the vexillum-like banners used by ancient Greek armies, such as the so-called phoinikis, a cloth of deep red, suspended from the top of a staff or spear. It is not known to have carried any device or decoration though.

The Byzantines, like the Romans before them, used a variety of flags and banners, primarily to denote different military units. These were generally square or rectangular, with a number of streamers attached.[6] Most prominent among the early Byzantine flags was the labarum. In the surviving pictorial sources of the middle and later Empire, primarily the illustrated Skylitzes Chronicle, the predominating colours are red and blue in horizontal stripes, with a cross often placed in the centre of the flag. Other common symbols, prominently featuring on seals, were depictions of Christ, the Virgin Mary and saints, but these represent personal rather than family or state symbols. Western European-style heraldry was largely unknown until the last centuries of the Empire.[7]

There is no mention of any "state" flag until the mid-14th century, when a Spanish atlas, the Conosçimiento de todos los reynos depicts the flag of "the Empire of Constantinople" combining the red-on-white Cross of St George with the "tetragrammatic cross" of the ruling house of the Palaiologoi, featuring the four betas or pyrekvola ("fire-steels") on the flag quarters representing the imperial motto Βασιλεύς Βασιλέων Βασιλεύων Βασιλευόντων ("King of Kings Reigning over those who Rule").[8] The tetragrammatic cross flag, as it appears in quarters II and III in this design, is well documented. In the same Spanish atlas this "plain" tetragrammatic cross flag is presented as (among other places in the Empire) "the Flag of Salonika" and "the real Greece and Empire of the Greeks (la vera Grecia e el imperio de los griegos)". The (quartered) arrangement that includes the Cross of St. George is documented only in the Spanish atlas, and most probably combines the arms of Genoa (which had occupied Galata) with those of the Byzantine Empire, and was most probably flown only in Constantinople.[9] Pseudo-Kodinos records the use of the "tetragrammatic cross" on the banner (phlamoulon) borne by imperial naval vessels, while the megas doux displayed an image of the emperor on horseback.[10]

Ottoman period

During the Ottoman rule several unofficial flags were used by Greeks, usually employing the Byzantine double-headed eagle (see below), the cross, depictions of saints and various mottoes.[9] The Christian Greek sipahi cavalry employed by the Ottoman Sultan were allowed to use their own, clearly Christian flag, when within Epirus and the Peloponnese. It featured the classic blue cross on a white field with the picture of St. George slaying the dragon,[citation needed] and was used from 1431 until 1639, when this privilege was greatly limited by the Sultan.[citation needed] Similar flags were used by other local leaders. The closest to a Greek "national" flag during Ottoman rule was the so-called "Graeco-Ottoman flag" (Γραικοθωμανική παντιέρα), a civil ensign Greek Orthodox merchants (better: merchants from the Greek-dominated Orthodox millet) were allowed to fly on their ships, combining stripes with red (for the Ottoman Empire) and blue (for Orthodoxy) colours. After the 1774 Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, Greek-owned merchant ships could also fly the Russian flag.

During the uprising of 1769 the historic blue cross on white field was used again by key military leaders, such as Olga the III, who used it all the way to the revolution of 1821. It became the most popular Revolution flag, and it was argued that it should become the national flag. The "reverse" arrangement, white cross on a blue field, also appeared as Greek flag during the uprisings. This design had apparently been used earlier as well, as a local symbol (a similar 16th or 17th century flag has been found near Chania).

A military leader, Yiannis Stathas, used a flag with white cross on blue on his ship since 1800. The first flag featuring the design eventually adopted was created and hoisted in the Evangelistria monastery in Skiathos in 1807. Several prominent military leaders (including Theodoros Kolokotronis and Andreas Miaoulis) had gathered there for consultation concerning an uprising, and they were sworn to this flag by the local bishop.[2]

Flag used by the Greek sipahis of the Ottoman army between 1431 and 1619

Flag used by the Greek sipahis of the Ottoman army between 1431 and 1619 Civil flag and ensign of the Principality of Samos (1835–1912)

Civil flag and ensign of the Principality of Samos (1835–1912) Flag of the Septinsular Republic (1800–1807), the first autonomous modern Greek state

Flag of the Septinsular Republic (1800–1807), the first autonomous modern Greek state National flag and ensign of the Cretan State

National flag and ensign of the Cretan State Flag of the Free State of Icaria

Flag of the Free State of Icaria

War of Independence

- Proposed flag of Greece as drawn by Rigas Feraios in his manuscripts.

- Bishop Germanos of Patras blessing the flag of the Greek revolutionaries at the Monastery of Agia Lavra, part of a popular legend regarding the start of the revolution of 1821, although it never actually happened.

Revolutionary flags

Prior and during the early days of the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), many different flags were designed, proposed, and used: by various Greek intellectuals in Western Europe, and by local leaders, chieftains, and regional councils. Aside from the cross, many of these flags featured saints, the phoenix (symbolising the rebirth of the Greek nation), mottoes such as "Freedom or Death" (Ελευθερία ή Θάνατος), or the fasces-like emblems of the Filiki Eteria, the secret society that organised the uprising.

The flag of Greece, as proposed by Rigas Feraios in 1797

The flag of Greece, as proposed by Rigas Feraios in 1797 Flag of the Sacred Band with phoenix and motto "from my ashes I'm reborn"

Flag of the Sacred Band with phoenix and motto "from my ashes I'm reborn" Flag of Alexander Ypsilantis

Flag of Alexander Ypsilantis  Flag of the Areopagus of Eastern Continental Greece

Flag of the Areopagus of Eastern Continental Greece The flag of Andreas Londos

The flag of Andreas Londos The flag of Krokodeilos Kladas

The flag of Krokodeilos Kladas Flag of the Filiki Eteria with initials of the motto "Freedom or Death"

Flag of the Filiki Eteria with initials of the motto "Freedom or Death" Flag of the Greeks of Thrace

Flag of the Greeks of Thrace Flag of the Maniots

Flag of the Maniots Used in Thessaly, created by Anthimos Gazis

Used in Thessaly, created by Anthimos Gazis Flag of Hydra island

Flag of Hydra island Flag of Spetses island

Flag of Spetses island Flag of Kastellorizo island

Flag of Kastellorizo island Flag of Athanasios Diakos

Flag of Athanasios Diakos Flag of the Military-Political System of Samos

Flag of the Military-Political System of Samos

Adoption

European monarchies, aligned in the so-called "Concert of Europe", were suspicious towards national or social revolutionary movements such as the Etaireia. The First Greek National Assembly, convening in January 1822, thus took steps to disassociate itself from the Etaireia's legacy and portray nascent Greece as a "conventional", ordered nation-state.[2] As such, not only were the regional councils abolished in favour of a central administration, but it was decided to abolish all revolutionary flags and adopt a universal national flag. The reasons why the particular arrangement (white cross on blue) was selected, instead of the more popular blue cross on a white field, remain unknown.[2]

On 15 March 1822, the Provisional Government, by Decree Nr. 540, laid down the exact pattern: white cross on blue (plain) for the land flag; nine alternate-coloured stripes with the white cross on a blue field in the canton for the naval ensign; and blue with a blue cross on a white field in the canton for the civil ensign (merchant flag).[1][2] On 30 June 1828, by decree of the Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias, the civil ensign was discontinued, and the cross-and-stripes naval ensign became the national ensign, worn by both naval and merchant ships.[2] This design became immediately very popular with Greeks and in practice was often used simultaneously with the national (plain cross) flag.

On 7 February 1828 the Greek flag was internationally recognised for the first time by receiving an official salutation from British, French, and Russian forces in Nafplio, then the capital of Greece.[11]

Greek flag on land, 1822–1969 and 1975–78 as adopted by the First National Assembly at Epidaurus

Greek flag on land, 1822–1969 and 1975–78 as adopted by the First National Assembly at Epidaurus- National flag for use abroad and as the civil ensign. Since 1978 the sole national flag of Greece

Civil ensign used from 1822 to 1828

Civil ensign used from 1822 to 1828- A darker variant of the national flag

Historical evolution

After the establishment of the Kingdom of Greece in 1832, the new king, Otto, added the royal coat of arms (a shield in his ancestral Bavarian pattern topped by a crown) in the centre of the cross for military flags (both land and sea versions).[1] The decree dated 4 (16) April 1833 provided for various maritime flags such as the war flag or naval ensign (set at 18:25), pennant, royal standard (set at 7:10) and civil ensign (i.e. the naval ensign without coat of arms).[12] A royal decree dated 28 August 1858 provided for details on the construction and dimensions concerning the flags described in the 1833 decree and other flags. After Otto's abdication in 1862, the royal coat of arms was removed.

In 1863, the 17-year old Danish prince William was selected as Greece's new king, taking on the name George I. A royal decree dated 28 December 1863 introduced crowns into the various flags in place of the coat of arms.[13] Similar arrangements were made for the royal flags, which featured the coat of arms of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg on a square version of the national flag. A square version of the land flag with St. George in the centre was adopted on 9 April 1864 as the Army's colours.[2][14] The exact shape and usage of the flags was determined by Royal Decree on 26 September 1867.[2][15] By a new Royal Decree, on 31 May 1914, the various flags of Greece and its military were further regulated. By this decree, the flag with the crown was adopted for use as a state flag by ministries, embassies and civil services, while the sea flag (without the crown) was allowed for use by private citizens.[2]

On 25 March 1924, with the establishment of the Second Hellenic Republic, the crowns were removed from all flags.[2] On 20 February 1930, the national flag's proportions were established at a 2:3 ratio, with the arms of the cross being "one fifth of the flag's width". The land version of the national flag was to be used by ministries, embassies, and in general by all civil and military services, while the sea flag was to be used by naval and merchant vessels, consulates and private citizens. On 10 October 1935, Georgios Kondylis declared that the monarchy had been restored. By decree of 7 November 1935, the 31 May 1914 decree was restored.[16] Thereby, the crown was restored on the various flags.[2] Compulsory Law 447 of 1937 described two types of flags allowed for use by private individuals: a fortress-type and a navy-type flag, both identical to the national land and sea flags, but without the crown.

Military dictatorship (1967–1974)

The legal provisions went unaltered for a relatively long period of time. In 1967, a new Compulsory Law (198) regulated the declaration of regional flag days, but did not alter the flag. However, on August 18, 1969, the sea flag was established as the sole national flag[17] and on August 18, 1970, the flag ratio was changed to 7:12 from 2:3.[2] Flags flying in ministries, embassies and public buildings had the crown in the centre of the cross until the official abolition of the monarchy on 1 June 1973 and the use of the crown was officially discontinued on July 16.[18]

After the restoration of democracy, Law 48/1975 and Presidential Decree 515/1975, which entered into effect on 7 June 1975, reversed the situation and designated the former "land flag" as the sole flag of Greece, to be used even at sea. The situation was once again reversed in 1978, when the sea flag once again became the sole flag of Greece and all previous provisions were abolished.[2]

- Sole national flag (1969–1970) Proportions: 2:3

- Sole national flag (1970–1975) Proportions: 7:12

Theories regarding the blue and white colours

Several Greek researchers[4][19][20] have attempted to establish a continuity of usage and significance of the blue and white colours, throughout Greek history.

Usages cited include the pattern of blue and white formations included on the shield of Achilles,[19][9] the apparent connection of blue with goddess Athena, some of Alexander the Great's army banners,[4] possible blue and white flags used during Byzantine times,[19][9] supposed coats of arms of imperial dynasties and noble families, uniforms, emperors' clothes, patriarchs' thrones etc.,[4][20] 15th century versions of the Byzantine Imperial Emblems [9] and, of course, cases of usage during the Ottoman rule and the Greek revolution.

On the other hand, the Great Greek Encyclopedia notes in its 1934 entry on the Greek flag that "very many things have been said for the causes which lead to this specification for the Greek flag, but without historical merit".[11]

Current flag of Greece

In 1978, the sea flag was adopted as the sole national flag, with a 2:3 ratio.[21] The flag is used on both land and sea is also the war and civil ensign, replacing all other designs surviving until that time. No other designs and badges can be shown on the flag. To date, no specification of the exact shade of the blue colour of the flag has been issued. Consequently, in practice hues may vary from very light to very dark. The Greek Flag Day is on 27 October.

The old land flag is still flown at the Old Parliament building in Athens, site of the National Historical Museum, and can still be seen displayed unofficially by private citizens.

Protocol

The use of the Greek flag is regulated by Law 851.[22] More specifically, the law states that:

- When displayed at the Presidential Palace, the Hellenic Parliament, the ministries, embassies and consulates of Greece, schools, military camps, and public and private ships as well as the navy, the flag must:

- Fly from 8am until sunset,

- Be displayed on a white mast topped with a white cross on top of a white sphere,

- Not be torn or damaged in any way. If the flag is damaged, it should be burned in a respectful manner.

- The flag can be displayed by civilians on days specified by the ministry of internal affairs, as well as in sporting events and other occasions of the sort.

- When displayed vertically, the canton must be on the left side of the flag from the point of view of the spectator.

- The flag should never be:

- Defaced by means of writing or superimposing any kind of image or symbol upon it,

- Used to cover a statue. In that case, cloth in the national colours must be used,

- Hung from windows or balconies without the use of a mast,

- Used for commercial purposes,

- Used as a logo for any corporation or organization, even at different proportions.

- When placed on top of a coffin, the canton must always be on the right of the person's head.

Colours

The government has not specified exactly which shade of blue should be used for the flag, and as such flags with many varying shades exist. In the most recent legislation regarding the national flag, the colours mentioned are:

The National Flag of Greece is cyan and white, it is made up of nine (9) stripes equal in width, of which five (5) are cyan and four (4) are white so that the upper and lower stripes are cyan and the others in between are white.

Because of the use of the word 'cyan' (Greek: κυανός, Kyanos), which can also mean 'blue' in Greek, the exact shade of blue remains ambiguous. Although it implies the use of a light shade of blue, such as on the flag of the United Nations, the colours of the Greek flag tend to be darker, especially during the dictatorship and in recent years, with the exception of the years of the rule of King Otto, when a very light shade of blue was used. Consequently, the shade of blue is largely left to the flagmakers to decide, as shown in the table below.

| White color | Blue color | Source | Year | URL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | #ffffff | 0% - 0% - 0% - 0% | 286 C | #005bae | 100% - 60% - 0% - 5% | Album des Pavillons | 2000 | [23] |

| White | #ffffff | 285 | #2175d8 | 2008 Summer Olympics Flag Manual | 2008 | [24] | ||

| White | #ffffff | Reflex Blue | #004C98 | 2012 Summer Olympics Flag Manual | 2012 | [25] | ||

Flag days

Law 851/1978 sets the general outline for when the specific days on which the flag should be raised.[22] For national holidays, this applies country-wide, but on local ones it only applies to those areas where the said holiday is being celebrated.[22] Additionally, the flag may also be flown on days of national mourning, half-mast. The Minister of the Interior has the authority to proclaim flag days if they are not already proclaimed, and proclaiming regional flag days is vested with the elected head of each regional unit (formerly prefectures).[22]

| Date | Name | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| 25 March | 25th of March | Anniversary of the traditional start date for the Greek War of Independence.[26] |

| 28 October | Ochi Day (No Day) | Anniversary of the refusal to accept the Italian ultimatum in 1940.[26] |

| 17 November | Polytechnic Day | Anniversary of the Athens Polytechnic uprising against the military junta (school holiday).[27] |

Although 17 November is not an official national holiday, Presidential Decree 201/1998 states that respects are to be paid to the flag on that particular day.[27]

Military flags

Army and Air Force War flag

The war flag (equivalent to regimental colours) of the Army and the Air Force is of square shape, with a white cross on blue background. On the centre of the cross the image of Saint George is shown on Army war flags and the image of archangel Michael is shown on Air Force war flags.[1]

In the Army war flags are normally carried by infantry, tank and special forces regiments and battalions, by the Evelpidon Military Academy, the Non-Commissioned Officers Academy and the Presidential Guard when in battle or in parade.[28] However, flying a war flag in battle is unlikely with current warfare tactics.

- Army regimental war flag

Naval and civil ensigns

The current naval and civil ensigns are identical to the national flag.

The simple white cross on blue field pattern is also used as the Navy's jack and as the base pattern for naval rank flags. These flags are described in Chapter 21 (articles 2101–30) of the Naval Regulations. A jack is also flown by larger vessels of the Hellenic Coast Guard.

Units of Naval or Coast Guard personnel in parade fly the war ensign in place of the war flag.[29]

- Naval jack of Greece

- Naval rank flag of the prime minister of Greece

- Naval rank flag for a full admiral

Coast Guard ensign (1973–1980)

Coast Guard ensign (1973–1980)

Other uniformed services

In the past a war flag was assigned to the former semi-military Hellenic Gendarmerie, which was later merged with Cities Police to form the current Hellenic Police. The flag was similar to the Army war flag but showing Saint Irene in place of Saint George.[29]

Since the Fire Service and the Hellenic Police are considered civilian agencies, they are not assigned war flags. They use the National Flag instead.[30] Identical rules were applied to the former Cities Police. However, recently the Police Academy has been assigned a war flag, and they paraded for the first time with this flag on Independence Day, March 25, 2011. The flag is similar to the Army war flag, with the image of St George replaced with that of Artemius of Antioch.[31]

Flag of the head of state

Throughout the history of Greece, various heads of state have used different flags. The designs differ according to the historical era they were used in and in accordance with the political scene in Greece at the time. The first flag to be used by a head of state of Greece was that of King Otto of Greece.

Following the establishment of the Kingdom of Greece in 1832, the 17-year old Bavarian prince Otto was selected as king for the newfound monarchy. A royal decree dated 4 (16) April 1833 prescribed a number of maritime flags, including the royal standard. This flag, set at a 7:10 ratio, was a variant of the Greek white-cross-on-blue and featured the ancestral coat of arms of the Wittelsbach dynasty at its centre. The construction and dimensions of this flag was further described by a decree dated 28 August 1858, which also changed the proportions of the flag from 7:10 to 3:2. Following Otto's abdication in 1862, the Wittelsbach coat of arms would subsequently be removed.

In 1863, the 17-year old Danish prince William was selected as Greece's new king, taking on the name George I. A royal decree dated 28 December 1863 prescribed that the king's standard would retain the same dimensions and basic design of the previous flag. At the flag's centre, the royal coat of arms of the new dynasty (Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg) would feature. By a new royal decree of 3 June 1914, the distinguishing flags to be utilised by the various members of the royal family were described. The king's flag was defined as being square in shape and, as in previous flags, featured the coat of arms of the king on a Greek white-cross-on-blue. As the king at the time, Constantine I, was made a field marshal the previous year, the coat of arms on his flag featured a heraldic representation of the Marshal's baton in twos, crossed behind his coat of arms.

With the establishment of the Second Hellenic Republic in 1924, the king's flag was made redundant. In 1930, a presidential decree described the president's flag as being a square version of the usual cross flag, devoid of any distinguishing markings.

On 10 October 1935, Georgios Kondylis declared that the monarchy had been restored and the 3 June 1914 decree was restored by decree of 7 November 1935. This flag, and the flags of other members of the royal family, was replaced the following year with new designs. Unlike previous designs, all flags now featured the coat of arms of the dynasty at its centre and would be distinguished by the number of crowns present at each of the four corners of the flags: The flag of the king featured a crown on each of the corners of the flag. This was the last design of a royal standard to be adopted prior to the eventual formal abolition of the monarchy in 1973.

The president's flag is currently prescribed by Presidential Decree 274/1979.[32]

Flag of King Constantine I of Greece in his capacity as a Field Marshal (1914–1917 and 1920–1922)

Flag of King Constantine I of Greece in his capacity as a Field Marshal (1914–1917 and 1920–1922)- Flag of the president of Greece (1979–present)

Use of double-headed eagle

One of the most recognisable and beloved Greek symbols, the double-headed eagle, is not a part of the modern Greek flag or coat of arms (although it is officially used by the Greek Army, the Church of Greece, the Cypriot National Guard and the Church of Cyprus, and was incorporated in the Greek coat of arms in 1926[9]). One suggested explanation [citation needed] is that, upon independence, an effort was made for political — and international relations — reasons to limit expressions implying efforts to recreate the Byzantine Empire. Yet another theory[citation needed] is that this symbol was only connected with a particular period of Greek history (Byzantine) and a particular form of rule (imperial).

Some Greek sources have attempted to establish links with ancient symbols: the eagle was a common design representing power in ancient city-states, while there was an implication of a "dual-eagle" concept in the tale that Zeus left two eagles fly east and west from the ends of the world, eventually meeting in Delphi, thus proving it to be the centre of the earth. However, there is virtually no doubt that its origin is a blend of Roman and Eastern influences. Indeed, the early Byzantine Empire inherited the Roman eagle as an imperial symbol. During his reign, Emperor Isaac I Comnenus (1057–59) modified it as double-headed, influenced by traditions about such a beast in his native Paphlagonia in Asia Minor (in turn reflecting possibly much older local myths). Many modifications followed in flag details, often combined with the cross. After the recapture of Constantinople by the Byzantine Greeks in 1261, two crowns were added (over each head) representing — according to the most prevalent theory — the newly recaptured capital and the intermediate "capital" of the empire of Nicaea. There has been some confusion about the exact use of this symbol by the Byzantines; it appears that, at least originally, it was more a "dynastic" and not a "state" symbol (a term not fully applicable at the time, anyway), and for this reason, the colours connected with it were clearly the colours of "imperial power", i.e., red and yellow/gold.

After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire nonetheless, the double-headed eagle remained a strong symbol of reference for the Greeks. Most characteristically, the Orthodox Church continues to use the double-headed eagle extensively as a decorative motif, and has also adopted a black eagle on yellow/gold background as its official flag.

After the Ottoman conquest, however, this symbol also found its way to a "new Constantinople" (or Third Rome), i.e. Moscow. Russia, deeply influenced by the Byzantine Empire, saw herself as its heir and adopted the double-headed eagle as its imperial symbol. It was also adopted by the Serbs, the Montenegrins, the Albanians and a number of Western rulers, most notably in Germany and Austria.

Flag of the Greek Orthodox Church

Flag of the Greek Orthodox Church Flag of the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus

Flag of the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus- Flag of the Hellenic Army General Staff

See also

- Greece

- Coat of arms of Greece

- Hymn to Liberty

- Byzantine heraldry

- History of Greece

- List of Greek flags

References

- ^ a b c d The Flag, from the site of the Presidency of the Hellenic Republic

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Alexander-Michael Hadjilyra: Η καθιέρωση της ελληνικής σημαίας ("The adoption of the Greek flag"), Hellenic Army General Staff, 2003.

- ^ The Flag Bulletin, Volumes 14–17, Flag Research Center, 1976, p. 63: "Greeks wanted this color for their flag because they have always looked at the blue sky and the blue ocean."

- ^ a b c d N. Zapheiriou, Η Ελληνική Σημαία από τους αρχαίους χρόνους μέχρι σήμερα (The Greek Flag from Antiquity to Present), Eleftheri Skepsis, Athens 1995 (reprint of original 1947 publication) ISBN 960-7199-60-X.

- ^ "ΟΙ ΚΑΛΛΕΡΓΗΔΕΣ". Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Emperor Maurice, Strategikon, II.14.

- ^ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. pp. 472, 999. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^ "Byzantine Heraldry, from Heraldica.org". Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f L. S. Skartsis, Origin and Evolution of the Greek Flag Archived 3 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Athens 2017 ISBN 978-960-571-242-6.

- ^ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. pp. 472–473. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^ a b Μεγάλη Ἐλληνικὴ Ἐγκυκλοπαιδεῖα [Greece - Hellenism] (in Greek). Vol. 10. Athens: Pyrsos Co. Ltd. 1934. p. 242. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Government of Greece (3 June 1833). "Περὶ τῆς πολεμικῆς καὶ ἐμπορικῆς σημαίας τοῦ Βασιλείου" [Regarding the Naval and Commercial Flag of the Kingdom]. Government Gazette. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ royal decree dated 28 December 1863. Gazette 5/1864, 3-2-1864, pages 16-17

- ^ "Gazette 16/1864, 25-4-1864, p. 85". Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Gazette 61/1867, 19-10-1867, pages 700-701". Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "ΦΕΚ 541/1935, dated 12.11.1935, page 2656". Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Nomothetikón Diátagma yp' arith. 254 Perí tís Ethnikís kaí tón Polemikón Simaión" Νομοθετικὸν Διάταγμα ὑπ’ ἀριθ. 254 Περὶ τῆς Ἐθνικῆς καὶ τῶν Πολεμικῶν Σημαιῶν [Legislative Decree No. 254 About the National and Military Flags]. Government Gazette of the Kingdom of Greece (in Greek). A (159). Athens: National Printing Office. 18 August 1969. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Legislative Decree 53/1973 On the amendment of certain provisions of the L.D. 254/69 "Regarding the National Flag and War Flags" (Government Gazette Issue A 144/1973)

- ^ a b c V. Tzouras, Η Ελληνική Σημαία, Μελέτη Πρωτότυπος Ιστορική (The Greek Flag, Original Historic Study), A. Lantzas, Kerkyra 1909

- ^ a b E. Kokkoni and G. Tsiveriotis, Ελληνικές Σημαίες, Σήματα-Εμβλήματα (Greek Flags, Signs and Emblems), Athens 1997 ISBN 960-7795-01-6

- ^ Law 851/21-12-1978 On the national Flag, War Flags and the Distinguishing Flag of the President of the Republic, Gazette issue A-233/1978.

- ^ a b c d Law 851 (in Greek) Archived 2013-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Album des pavillons nationaux et des marques distinctives. Brest, France: S.H.O.M. 2000. p. 238.

- ^ Flag Manual. Beijing, China: Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad – Protocol Division. 2008. p. B15.

- ^ Flags and Anthems Manual. London, United Kingdom: London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Limited. 2012. p. 47.

- ^ a b "Procedural time limits - Greece". Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Presidential Decree 201/1998" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ O. Zotiadis (January 2001). "Decorations of War Flags (Greek: Τιμητικές διακρίσεις πολεμικών σημαιών)". Military Review. Hellenic Army General Staff.

- ^ a b Presidential Decree 348 /17-4-1980, On the war flags of the Armed Forces and the Gendarmerie Corps, Gazette issue A-98/1980 Archived 29 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Presidential Decree 991/7-10-1980, Specification of the size of the National Flag born by the Coast Guard, Cities Police and Fire Service and the length of its staff, Gazette issue A-247/1980.

- ^ "Σχολή Αξιωματικών Ελληνικής Αστυνομίας". Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ published in Gazette A, 78, dated 17.04.1979, p.726

Further reading

- Mazarakis-Ainian, Ioannis. Η Ιστορία της Ελληνικής Σημαίας. Nicosia, Cyprus: Cultural Foundation of the Bank of Cyprus. 1996. (In Greek).

- I. Nouchakis, Η Σημαία μας (Our Flag), Athens 1908.

External links

Media related to National flag of Greece at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to National flag of Greece at Wikimedia Commons- Flags of Greece at Flags of the World

- Article on the Greek Flag from the website of the Hellenic Army (in Greek)

- Older article on the Greek Flag from the website of the Hellenic Army (in Greek)

- Greek flags during the Ottoman era (in Greek)

- Decrees specifying the design of the flag:

- Regarding the Naval and Commercial Flag of the Kingdom (3 June 1833) – contains official drawings

- Regarding the Naval and Commercial Flag (13 September 1858)

- Regarding the Flags of the Kingdom of Greece and other distinctive ensigns (31 May 1914) – contains numerous official drawings

- Regarding the flag of Greece and other distinctive ensigns (25 February 1930)

- Regarding the National and War Flags (18 August 1969) – changed the proportions to 7:12 and abolished the state flag

- Regarding amendments to provisions subject to Legislative Decree 254/69 (29 January 1971) – removed the royal crowns from all flags

- Law 48 Regarding the National Flag of Greece, the Emblem of the Hellenic Republic, etc (7 June 1975) – restored the old proportions and the state flag

- Law 851 Regarding the National Flag, the War Flags and the Emblem of the President of the Republic (22 December 1978) – current flag design