Greater bamboo lemur

| Greater bamboo lemur | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Ranomafana National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | Lemuridae |

| Genus: | Hapalemur |

| Species: | H. simus |

| Binomial name | |

| Hapalemur simus J. E. Gray, 1871[3] | |

| |

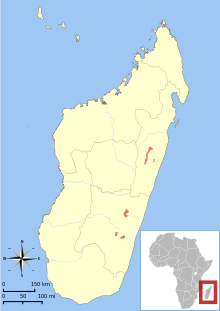

| Distribution of H. simus[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The greater bamboo lemur (Hapalemur simus), also known as the broad-nosed bamboo lemur and the broad-nosed gentle lemur, is a species of lemur endemic to the island of Madagascar.

Taxonomy

Originally described as Hapalemur (Prolemur) simus by John Edward Gray in 1870,[4] it was regarded simply as Hapalemur simus as early as 1880.[5] With the understanding that this species is more closely related to the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) than to the other Hapalemur species, Colin Groves resurrected Prolemur as a full genus in 2001, with this species as its only member.[6] More recent research by Herrera and Dávalos (2016) indicates that the species is sister to all of Hapalemur, and that Lemur is sister to Hapalemur + simus, and that it should remain in Hapalemur.[7]

Description

The greater bamboo lemur is the largest bamboo lemur, at over 5 lb (2.3 kg). It has greyish brown fur and white ear tufts, and has a head-body length of around 1.5 ft (46 cm). They have relatively long tails and long back legs for leaping vertically amongst the trees of their forest habitat.

Predators

Its only confirmed predators are the fossa and the bush pigs,[8] but raptors are also suspected. Protection from predators, avoiding parasite vectors, and enhanced thermoregulation are three theories that are not mutually exclusive to explain the selection of sleeping location.[9] The fossa hunts the Great bamboo lemurs in large numbers. As a result, the lemurs must maintain a secure sleeping environment, such as tree holes and constructed nests.

Habitat

Its current range is restricted to southeastern Madagascar, although fossils indicate its former range extended across bigger areas of the island, including as far north as Ankarana.[10][11] Some notable parts of the current range are the Ranomafana[12] and Andringitra National Parks.[citation needed]

Behavior

Greater bamboo lemurs live in groups of up to 28. Individuals are extremely gregarious. The species may be the only lemur in which the male is dominant, although this is not certain. Because of their social nature, greater bamboo lemurs have at least seven different calls. Males have been observed taking bamboo pith away from females that had put significant effort into opening the bamboo stems. In captivity, greater bamboo lemurs have lived over the age of 17.[13]

Diet

It feeds almost exclusively on the bamboo species of Cathariostachys madagascariensis, preferring the shoots but also eating the pith and leaves. It is unknown how their metabolism deals with the cyanide found in the shoots. The typical daily dose would be enough to kill humans. Greater bamboo lemurs occasionally consume fungi, flowers, and fruit. Its main food source is bamboo and it is the main reason why it has become critically endangered.[14][8] Areas with high density of bamboo have major human disturbances, where humans cut or illegally cut down bamboo.[15]

Conservation status

The greater bamboo lemur (Hapalemur simus), is one of the world's most critically endangered primates, according to the IUCN Red List. Scientists believed that it was extinct, but a remnant population was discovered in 1986.[16] Since then, surveys of south- and central-eastern Madagascar have found about 500 individuals in 11 subpopulations.[1] The home range of the species is likewise drastically reduced. The current range is less than 4 percent of its historic distribution. The reason for the endangerment is climate change and human activities which depleted the primary food source (bamboo). Greater bamboo lemur is a part of prosimian species, which appeared even before monkeys. This species of lemur is not capable of adapting to the rapidly changing habitat. Human activities and climate change have resulted in the depletion of populations and resulted in a few remaining patches of forest capable of supporting this species. The species is endangered by the following: slash and burn farming, mining, bamboo, and other logging, and slingshot hunting.[13] It was formerly one of "The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates."[17] As of October 2024, only 36 individuals are in captivity, world-wide.[18]

References

- ^ a b c Ravaloharimanitra, M.; King, T.; Wright, P.; Raharivololona, B.; Ramaherison, R.P.; Louis, E.E.; Frasier, C.L.; Dolch, R.; Roullet, D.; Razafindramanana, J.; Volampeno, S.; Randriahaingo, H.N.T.; Randrianarimanana, L.; Borgerson, C.; Mittermeier, R.A. (2020). "Prolemur simus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T9674A115564770. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T9674A115564770.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Checklist of CITES Species". CITES. UNEP-WCMC. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ a b Groves, C. P. (2005). "Species Prolemur simus". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). "Genus Prolemur". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Schlegel, H. (1880). "Hapalemur simus". Notes from the Leyden Museum.

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2001). Primate taxonomy. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 350. ISBN 156098872X.

- ^ Herrera, James P.; Dávalos, Liliana M. (September 2016). "Phylogeny and Divergence Times of Lemurs Inferred with Recent and Ancient Fossils in the Tree". Systematic Biology. 65 (5): 772–791. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syw035. PMID 27113475.

- ^ a b Ravaloharimanitra, Maholy; Ratolojanahary, Tianasoa; Rafalimandimby, Jean; Rajaonson, Andry; Rakotonirina, Laingoniaina; Rasolofoharivelo, Tovonanahary; Ndriamiary, Jean Noel; Andriambololona, Jeannot; Nasoavina, Christin; Fanomezantsoa, Prosper; Rakotoarisoa, Justin Claude (17 February 2011). "Gathering Local Knowledge in Madagascar Results in a Major Increase in the Known Range and Number of Sites for Critically Endangered Greater Bamboo Lemurs (Prolemur simus)". International Journal of Primatology. 32 (3): 776–792. doi:10.1007/s10764-011-9500-4. ISSN 0164-0291. S2CID 32431392.

- ^ Eppley, Timothy M. (21 January 2016). "Unusual sleeping site selection by southern bamboo lemurs". Primates. 57 (2): 167–173. doi:10.1007/s10329-016-0516-4. PMID 26860934. S2CID 8025412.

- ^ Godfrey, L.R.; Wilson, Jane M.; Simons, E.L.; Stewart, Paul D.; Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, M. (1996). "Ankarana: window to Madagascar's past". Lemur News. 2: 16–17.

- ^ Wilson, Jane M.; Godfrey, L.R.; Simons, E.L.; Stewart, Paul D.; Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, M. (1995). "Past and Present Lemur Fauna at Ankarana, N. Madagascar". Primate Conservation. 16: 47–52.

- ^ Wilson, Jane (1995). Lemurs of the Lost World: exploring the forests and Crocodile Caves of Madagascar. Impact, London. pp. 139–143. ISBN 978-1-874687-48-1.

- ^ a b Conniff, Richard (April 2006). "For the Love of Lemurs". Smithsonian. 37 (1). Smithsonian Institution: 102–109.

- ^ Hawkins, Melissa T. R.; Culligan, Ryan R.; Frasier, Cynthia L.; Dikow, Rebecca B.; Hagenson, Ryan; Lei, Runhua; Louis, Edward E. (8 June 2018). "Genome sequence and population declines in the critically endangered greater bamboo lemur (Prolemur simus) and implications for conservation". BMC Genomics. 19 (1): 445. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4841-4. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 5994045. PMID 29884119.

- ^ Olson, Erik R.; Marsh, Ryan A.; Bovard, Brittany N.; Randrianarimanana, H. L. Lucien; Ravaloharimanitra, Maholy; Ratsimbazafy, Jonah H.; King, Tony (30 April 2013). "Habitat Preferences of the Critically Endangered Greater Bamboo Lemur (Prolemur simus) and Densities of One of Its Primary Food Sources, Madagascar Giant Bamboo (Cathariostachys madagascariensis), in Sites with Different Degrees of Anthropogenic and Natural Disturbance". International Journal of Primatology. 34 (3): 486–499. doi:10.1007/s10764-013-9674-z. ISSN 0164-0291. S2CID 14975585.

- ^ Wright, Pat (July 2008). "A Proposal from Greater Bamboo Lemur Conservation Project". SavingSpecies. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Mittermeier, R.A.; Wallis, J.; Rylands, A.B.; Ganzhorn, J.U.; Oates, J.F.; Williamson, E.A.; Palacios, E.; Heymann, E.W.; Kierulff, M.C.M.; Yongcheng, L.; Supriatna, J.; Roos, C.; Walker, S.; Cortés-Ortiz, L.; Schwitzer, C., eds. (2009). Primates in Peril: The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates 2008–2010 (PDF). Illustrated by S.D. Nash. Arlington, VA: IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), and Conservation International (CI). pp. 1–92. ISBN 978-1-934151-34-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Cotswold wildlife park successfully breeds endangered Madagascan lemur". The Guardian. 20 October 2024. Retrieved 22 October 2024.