Gothic War (401–403)

| Gothic War (401-403) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Gothic Wars and Roman–Germanic Wars | |||||||

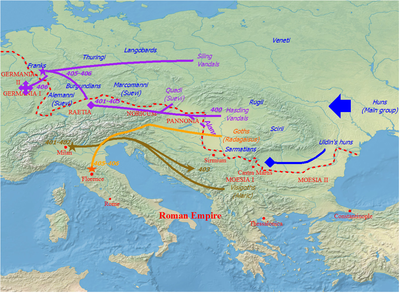

Map of Northern Italy | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Western Roman Empire | Visigoths | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Stilicho | Alaric I | ||||||

The Gothic War of 401–403 fought between the Western Roman Empire and the Visigoths. The commander of the Roman army was Flavius Stilicho, the Visigoths were led by Alaric. The war was fought in the north of Italy and, in addition to a number of small fights, consisted of two major battles, both of which were won by the Romans.

Background

After the death of Emperor Theodosius I, the empire was split into a Western Roman Empire and an Eastern Roman Empire. It was not clear where the dividing line exactly lay. A problem arose when in 395 Alaric, a former general in the Roman army and king of the Visigoths, revolted and invaded Greece (Gothic revolt of Alaric I). Stilicho, the commander-in-chief of the western armies, and shortly before his superior, wanted to drive him back, but was repulsed by the Eastern Authority, because he moved outside his territory.

After Stilicho was gone the Goths still were a threat for the Eastern Empire and because they did not have enough manpower to face them alone, they agreed a peace agreement with the Goths in 398. In doing so, the Eastern Empire made all kinds of commitments to the Goths. Alarik obtained the title of magister militum per Illyricum,[1] which meant that he held the highest military rank in this province. They also agreed to the settlement of the Goths in the Illyricum prefecture which was disputed with the Western Empire.[2]

The war

Prelude

It is unclear why Alaric moved west. The ancient sources do not indicate for what purpose Alaric invaded northern Italy. What is certain, is that the Gothic revolt of Tribigild, followed by the coup d'état of Gainas in the Eastern Roman Empire, turned to be unfavorable for the Goths in Illyricum. Gainas, commander-in-chief of the army and the new strongman, saw Alaric as a competitor. Taking advantage of his power, Gainas ordered the emperor Arcadius to renounce the services of Alaric and to cede the province of Illyricum, where the Visigoths stayed, to the West.

Due to this administrative change, Alaric lost his military rank of general and the right to legal provisions for his men. Gainas hoped to lose a dangerous opponent to the Western Empire with this. [3] However Gainas was overthrown with the help of the Huns of Uldin, which may also has been a reason for Alaric to move west.[4] Historian Thomas Burns suggests that Alaric was probably desperate for provisions to feed his army. [5]

Using Claudianus as his source, historian Guy Halsall reports that Alaric's attack actually began in late 401, but since Stilicho was in Raetia "to settle border matters", the two only met for the first time in Italy in 402. [6]

Stilicho's campaign in the North

Stilicho had assembled a large army in northern Italy. [7] [8] With this army he planned in 401 to march against the Vandals and Alans, who posed a major threat to the Western Roman Empire. The Vandals and Alans themselves were hunted by the Huns and the border provinces Raetia and Noricum were in danger of being overrun by the drifting peoples. After Stilicho had completed his preparations, he marched with the imperial army to the North against the invaders.

Siege of Asti

Alaric took advantage of this troop movement by invading the Prefecture of Italia, which happened in the autumn of that year. [9] Alaric's entry into Italy followed the route indicated in Claudian's poetry, when he crossed the Alpine border of the peninsula near the city of Aquileia. Over a period of six to nine months there were reports of Gothic attacks along the northern Italian roads, where Alaric was spotted by Roman travelers. Without encountering much resistance, he marched plundering to Mediolanum (Milan), where Emperor Honorius was staying. The emperor hastily fled from the rapid advance of the Goths, but did not get further than the city of Hasta, which was soon besieged by Alaric.

Stilicho stayed with the main force north of the Alps. The approaching winter prevented him from relieving the emperor. As soon as the Alpine passes permitted in March 402, Stilicho returned to Italy with a selected vanguard. Alaric first encountered Stilicho along the route over the Via Postumia. In doing so he forced Alaric to break the siege. [10]

Battles of Pollentia and Verona

Two battles were fought. The first was at Pollentia on 4 April 402 (Easter Sunday), where Stilicho (according to Claudian) won an impressive victory by capturing Alaric's wife and children, and more importantly, by seizing much of the treasure take that Alaric had captured over the past five years. [11] Stilicho pursued Alaric's retreating troops and offered to return the prisoners, but was refused. The second battle was at Verona, where Alaric was defeated for the second time. [11]

Despite the defeat, Alaric was given a free retreat by Stilicho. Stilicho offered Alaric a truce and allowed him to withdraw from Italy. He was allowed to travel to Illyria with his remaining troops and even received financial support for food. Kulikowski explains this confusing, if not outright conciliatory behavior by stating: "given Stilicho's cold war with Constantinople, it would have been foolish to destroy a potential weapon as biddable and violent, as Alaric might later prove to be". Halsall's observations are similar, as he argues that the Roman general's "decision to allow Alaric's withdrawal to Pannonia makes sense when we see that Alaric's force falls into the service of Stilicho and that Stilicho's victory is less total than Claudianus us wants to make you believe". [12] Perhaps more revealing is the account of the Greek historian Zosimus - who wrote half a century later: "which indicates that an agreement was made between Stilicho and Alaric in 405" - suggesting that Alaric was at that time in 'western service', probably as a result of an arrangement made in 402. [13] Between 404 and 405, Alaric stayed in one of the four Pannonian provinces, from which he could "play East against West while potentially threatening both".

Consequences

A direct consequence of this war was the relocation of the Emperor's residence to Ravenna. Milan, the city where Emperor Honorius stayed, turned out not to be so safe after all. Therefore, it was decided to move the court to Ravenna, a city surrounded by a swampy area. The only access was an artificial road, which could easily be defended if necessary. The Roman victory was initially received with joy by the population and Honorius went to Rome to celebrate the triumph in the company of his general.

According to historian A.D. Lee, Alaric's return to the northwestern Balkans brought Italy only a temporary reprieve, for a new war broke out when in 405 another Gothic tribe joined with other barbarians, this time from outside the empire, crossed the middle Danube and advanced into northern Italy, where they plundered the countryside and besieged towns and villages. This tribe was led by Radagaisus. [14] Although the imperial government struggled to muster sufficient troops to contain these barbarian invasions, Stilicho managed to quell the tribal threat under Radagaisus when he split his forces into three separate groups. Stilicho cornered Radagaisus near Florence and starved the invaders into submission. [14] Meanwhile, Alaric - who had been given the codicils of magister militum by Stilicho and was now being held by the West - waited delivered - on one side or the other to incite him to action, causing Stilicho to face difficulties from even more barbarians.[15]

Sources

- Claudius Claudianus

- Aurelius Prudentius Clemens

- Zosimus, Historia Nov.

- Blockley, R.C. (1998). "The Dynasty of Theodosius". In Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History.

- Burns, Thomas S. (1994). Barbarians within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, CA. 375–425 A.D. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253312884.

- Gibbon, Edward (1781). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

- Halsall, Guy (2007). Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge University Press.

- Hughes, Ian (2010). Stilicho: The Vandal Who Saved Rome. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military.

- Kulikowski, Michael (2006). Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84633-2.

- Kulikowski, Michael (2019). The Tragedy of Empire: From Constantine to the Destruction of Roman Italy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674660137.

- Lee, A.D. (2013). From Rome to Byzantium AD 363 to 565: The Transformation of Ancient Rome. Edinburgh University Press.

- Schreiber, Hermann (1979). De Goten, Vorsten en vazallen, Amsterdam: Meulenhoff ISBN 9789010024169.

References

- ^ Kulikowski 2019, p. 126.

- ^ Blockley 1998, p. 115.

- ^ Burns 1994, p. 175.

- ^ Blockley 1998, p. 117.

- ^ Burns 1994, p. 190.

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 201.

- ^ Hughes 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Claudius Claudianus, de Bello Getico, 279-80; 348-9; 363-5; 400f.

- ^ Hughes 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Gibbon 1781, p. 1.055.

- ^ a b Kulikowski 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 201–202.

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 202.

- ^ a b Lee 2013, p. 112.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, pp. 170–171.