Gold ground

Gold ground (both a noun and adjective) or gold-ground (adjective) is a term in art history for a style of images with all or most of the background in a solid gold colour. Historically, real gold leaf has normally been used, giving a luxurious appearance. The style has been used in several periods and places, but is especially associated with Byzantine and medieval art in mosaic, illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings, where it was for many centuries the dominant style for some types of images, such as icons. For three-dimensional objects, the term is gilded or gold-plated.

Gold in mosaic began in Roman mosaics around the 1st century AD, and originally was used for details and had no particular religious connotation, but in Early Christian art it came to be regarded as very suitable for representing Christian religious figures, highlighting them against a plain but glistering background that might be read as representing heaven, or a less specific spiritual plane. Full-length figures often stand on more naturalistically coloured ground, with the sky in gold, but some are shown fully surrounded by gold. The style could not be used in fresco, but was adapted very successfully for miniatures in manuscripts and the increasingly important portable icons on wood. In all of these the style required a good deal of extra skilled work, but because of the extreme thinness of the gold leaf used, the cost of the gold bullion used was relatively low; lapis lazuli blue seems to have been at least as expensive to use.[1]

The style remains in use for Eastern Orthodox icons to the present day, but in Western Europe fell from popularity in the Late Middle Ages, as painters developed landscape backgrounds. Gold leaf remained very common on the frames of paintings. There were pockets of revivalist use thereafter, as for example in Gustav Klimt's so-called "Golden period". It was also used in Japanese painting and Tibetan art, and sometimes in Persian miniatures and at least for borders in Mughal miniatures.

Writing in 1984, Otto Pächt said "the history of the colour gold in the Middle Ages forms an important chapter which has yet to be written",[2] a gap which perhaps has still only been partly filled.[3] Apart from large gold backgrounds, another aspect was chrysography or "golden highlighting", the use of gold lines in images to define and highlight features such as the folds of clothing. The term is often extended to include gold lettering and linear ornamentation.[4]

Effects

Recent scholarship has explored the effects of gold ground art, especially in Byzantine art, where the gold is best understood as representing light. Byzantine theology was interested in light, and could distinguish several different kinds of it. The New Testament and patristic accounts of the Transfiguration of Christ were an especial focus of analysis, as Jesus is described as emitting or at least bathed in a special light, whose nature was discussed by theologians. Unlike the main late medieval theory of optics in the West, where the viewer's eye was believed to emit rays that reached the viewed object, Byzantium believed the light proceeded from the object to the viewer's eye, and Byzantine art was very sensitive to alterations in the light conditions in which art was seen.[5]

Otto Pächt wrote that "medieval gold ground was always interpreted as a symbol of transcendental light. In the light transmitted by the gold of Byzantine mosaics there was eternal cosmic space dissolved at its most palpable in the unreal, or even, in the supernatural; and yet our senses are directly touched by this light."[6]

According to one scholar, "in a gold ground painting, the sacred image the Virgin, for example was firmly located on the material surface of the picture plane. She was, in this way, real, and the painting as much presented the Madonna as represented her ... [gold ground paintings] ...which blurred the distinction between the subject and its representation, were considered to have a physical and psychological presence like that of a real person."[7]

Technique

In mosaics the figures and other areas in colours were normally added first, then the gold placed around them. In painting the opposite sequence was used, with the figures "reserved" around their outline in the underdrawing.[8]

Mosaic

Gold leaf was glued to glass sheets about 8 mm thick with gum arabic, then a very thin extra layer of glass added on top for durability. In ancient times, the technique of creating "gold sandwich glass" was already known in Hellenistic Greece by around 250 BC, and used for gold glass vessels. In mosaics the top layer was applied by covering the sheet with powdered glass and firing the sheet enough to melt the powder and fuse the layers.[9] In 15th-century Venice the method changed and the top layer of molten glass was blown onto the other two at high temperature. This gave a better bond at the weakest point of a tessera, when the gold joined the thicker bottom layer of glass.[10]

The sheets of glass were then broken into small tesserae. There are then two methods of fixing to the wet cement on a prepared wall, which already had a number of different layers of plaster, sometimes giving as much as 5 cm between the stone or brick of the wall and the glass. Either the tesserae were individually pushed into place onto the wall, which gave a slightly uneven surface with tesserae at different angles. These could to some extent be controlled by the artisan, and allowed for subtle shimmering effects as light fell onto the surface. The other method was to use a water-soluble glue to fix the tesserae face down to a thin sheet; in modern times this is paper. The sheet was then pressed into the cement on the wall, and when this had dried the paper and glue are wetted and scrubbed away. This gives a much smoother surface.[11]

Painting

There are a number of different methods for applying the gold. The prepared surface of wood or vellum to be painted was underdrawn with at least the outlines of the figures and other elements. Then (or perhaps before) a layer of a reddish clay mix called bole was added. This gave depth to the gold colour, and prevented a greenish tinge that gold leaf on a white background tended to display. After several centuries, this layer is often revealed where the gold leaf has been lost.[12]

On top of this the gold leaf was added. Most commonly this was done a whole "leaf" at a time, by the water gilding technique. The leaf could then be "burnished", carefully rubbed with either the tooth of a dog or wolf, or a piece of agate, giving a brightly shining surface. Alternatively mordant gilding was used, which needed to be left as unburnished leaf giving a more muted effect. After several hundred years the different appearance of the two is often greatly reduced for modern viewers.[13]

Shell gold was gold paint with powdered gold as its pigment. This was generally used only for small areas, usually details and highlights within the coloured parts of the painting. The name came from the habit of using seashells to hold mixed paint of all types when painting. "Gilded applied relief" was unburnished gold leaf applied by mordant gilding to a moulded relief surface of gesso or pastiglia. The flat surfaces might then be "tooled" with punches and line-making tools, to make patterns within the gold, very often on halos or other features, but sometimes all over the background. Several of these techniques might be used on the same piece to give a variety of effects.[14]

Manuscripts

Any gold leaf was applied, and usually burnished, before painting began.[15] According to Otto Pächt, it was only in the 12th century that Western illuminators learnt how to achieve the full burnished gold leaf effect from Byzantine sources. Previously, for example in Carolingian manuscripts, "a gold pigment of sandy, grainy character, with only a faint glitter, was used."[16] The techniques in manuscript painting are similar to those for panel paintings, though on a smaller scale. One difference, both in Western and Islamic works, is that the gesso or bole ground is reduced in depth at its edges, giving the gold areas a very slight curve, which makes gold reflect the light differently. In manuscripts silver could also be used, but this has now generally oxidized to black.[17]

History

Paintings

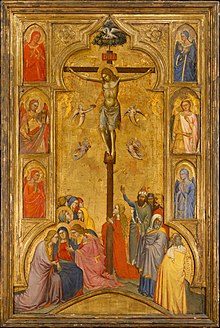

In the West, the style was usual in Italo-Byzantine icon-style paintings from the 13th century onwards, inspired by the Byzantine icons reaching Europe after the Sack of Constantinople in 1204. These soon developed into the polyptych wooden-framed altarpiece, which also usually used the gold ground style, especially in Italy. By the end of the century, increased numbers of Italian frescos were developing naturalistic backgrounds, as well as effects of mass and depth.[18] This trend began to spread to panel paintings, although many still used the golden backgrounds until well into the 14th century, and indeed beyond, especially in more conservative centres such as Venice and Siena, and for major altarpieces. Lorenzo Monaco, who died about 1424, represents "the final gasp of gold-ground brilliance in Florentine art".[19]

In Early Netherlandish painting the gold ground style was initially used, as in the Seilern Triptych of c. 1425 by Robert Campin, but a few years later his Mérode Altarpiece is given a famously detailed naturalistic setting.[20] The "near-elimination of gold backgrounds began in early Netherlandish painting around the mid-1420s", and was fairly rapid, with some exceptions like Rogier van der Weyden's Medici Altarpiece, which was probably painted after 1450, perhaps for an Italian patron who requested the earlier style.[21]

By the late 15th century the style represented a deliberate archaism, which was sometimes still used. The Roman painter Antoniazzo Romano and his workshop continued to use it into the first years of the 16th century, as he "made a speciality of repainting or interpreting older images, or generating new cult images with an archaic flavor",[22] Carlo Crivelli (died c. 1495), who for much of his career worked for relatively provincial patrons in the Marche region, also made late use of the style, to achieve sophisticated effects.[23] Joos van Cleve painted a gold ground Salvator Mundi in 1516–18 (now Louvre).[24] Albrecht Altdorfer's Crucifixion of c. 1520 in Budapest is a very late example, that also "reprises an iconographic type (the "Crucifixion with Crowd") and a non-naturalistic approach to space long out of fashion."[25]

Greek painters continued emulating the Byzantine masters in Crete and the Ionian Islands. Most Italian painters adopted oil painting opposing the egg tempera technique. Giorgio Vasari's famous book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects commented on the technique. Vasari coined the phrase Maniera Greca. By the mid-1500s the style was considered the Maniera Greca. It was one of the first post-classical European terms for style in art.[26] The technique was used from 1400 to 1830s in both the Cretan School and the Heptanese School. Michael Damaskinos began to mix Venetian painting and the traditional Greek Italian Byzantine painting style. The technique became an important component of the Cretan School. Gilded backgrounds were important to the painters but they escaped tradition by adopting modern Italian painting techniques.[27]

By the 1600s, painters began to adopt variations to their painting styles. During the mid 1600s Greek painters in the Venetian world utilized the flemish artistic style. While continuing the tradition of the gilded background they painted works featuring complex three-dimensional figures.

Theodore Poulakis integrated the gilded technique in most of his modernized paintings, one example was his work entitled Noah's Ark. Clearly, the painter intentionally replaces the sky in his work with gold sheet while maintaining the modern flemish painting style escaping the Greek Italian Byzantine tradition.[28] Another painter who emulated Titian's work was Stephanos Tzangarolas. Tzangarolas used Madonna Col Bambino as his inspiration to paint Virgin Glykofilousa with the Akathist Hymn. The gold-gilded background exults the theological figures into a supreme realm. Each biblical story in the painting is inlaid with gold. The traditional style is often continued in the Greek world until today.[29]

In later periods of European art, the style was sometimes revived, usually just with gold paint. In 1762 George Stubbs painted three compositions with racehorses on a blank gold or honey background, much the largest being Whistlejacket (now National Gallery). All were for their owner, the Marquess of Rockingham, who may have suggested the idea.[30] Given his passion for "the turf", there was possibly a joke on his high regard for the horses. In the 19th century the style became popular for church paintings in Gothic Revival architecture, and was used for ceilings or smaller high up lunettes in large public or church buildings, loosely recalling Byzantine precedents, reflecting the light and also saving the trouble of painting backgrounds. The paintings in the staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna by Hans Makart (1881–84) are one example of many. Another are the ceiling paintings Lord Leighton painted (exhibited Royal Academy 1886) for the Manhattan home of Henry Marquand, which he insisted use a painted gold ground rather than the "sylvan setting" the patron wanted for the figures, from classical mythology, saying in an interview: "if you look into it you will find it a luminous surface…. Viewing the pictures from this point you get a brilliant effect, like the brightness of day upon it; if from the other side you observe the light resolves itself into the rich, warm glow of the setting sun".[31]

Gustav Klimt's "Golden Phase" lasted from about 1898 and 1911, and included some his best-known paintings, including The Kiss (1907–08), the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), and the frieze in the Stoclet Palace (1905–11). The last was designed by Klimt and executed in mosaic by Leopold Forstner, an artist who did much work in mosaic including gold. Apparently Klimt's interest in the style intensified after a visit to Ravenna in 1903, where his companion said that "the mosaics made an immense, decisive impression on him".[32] He used large amounts of gold leaf and gold paint in a variety of ways, for the clothes of his subjects as well as the backgrounds.[33]

- 14th-century Italian Crucifixion by Allegretto Nuzi; much of the gold leaf has worn away, revealing the red bole below.

- Antoniazzo Romano, Virgin and Child with donor portrait, c. 1480

- Erato, by Lord Leighton, 1886, one of a ceiling set for Henry Marquand

Japanese painting

In Azuchi–Momoyama period Japan (1568–1600), the style became used in the large folding screens (byōbu) in the shiro or castles of the daimyo families by the late 16th century. The subjects included landscapes, birds and animals, and some crowded scenes from literature, or of everyday life. These were used in the rooms used for entertaining guests, while those for the family tended to use screens with ink and some colours. Gold leaf squares were used on paper, with their edges sometimes left visible.[34] These rooms had rather small windows, and the gold reflected light into the room; ceilings might be decorated the same way.[35] The full background might be in gold leaf, or sometimes just the clouds in the sky.[36] The Rinpa school made extensive use of gold ground.[37]

In Kano Eitoku's Cypress Trees screen (c. 1590), most of the "sky" behind the trees is gold, but the coloured areas of the foreground and the distant mountain peaks show that this gold is intended to represent a mountain mist. The immediate foreground surface is also a duller gold. Alternatively, backgrounds could be painted with a thin gold wash, allowing for more variation in effect in landscapes.[38] The style was not so suitable for Japanese scroll paintings, which were often kept rolled up. Some smaller wooden panels were given gold leaf backgrounds.[39]

Mosaics

It was only in the 1st and 2nd centuries that wall, as opposed to floor, mosaics became common in the Greco-Roman world, at first for damp tombs and nymphea, before being used in religious settings by the late 4th century. At first they were concentrated on or around the apse and sanctuary behind the main altar.[40] It was found that "by careful lighting, they seemed to not to enclose but to enlarge the space which they surrounded".[41]

One of the earliest surviving groups of gold-ground mosaics, from before about 440, is in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, on the "triumphal arch" and nave (the apse mosaics are much later), although those in the nave are placed too high to be seen clearly. The amount of gold background varies between scenes, and is often mixed with architectural settings, blue skies, and other elements. Later, mosaic became "the vehicle of choice for conveying the truth of Orthodox beliefs", as well as "the imperial medium par excellence".[42]

The traditional view, now challenged by some scholars, is that patterns of mosaic use spread from the court workshops of Constantinople, from which teams were sometimes despatched to other parts of the empire, or beyond as diplomatic gifts, and that their involvement can be deduced from the relatively higher quality of their production.[43]

Manuscripts

Technically, the term illuminated manuscript is limited to manuscripts whose pages are embellished with metals, of which gold is the most common. However, in modern usage manuscripts with miniatures and initials only using other colours are normally covered by the term.[44]

In manuscripts gold was used in the larger letters and borders as much as for a full background to miniatures. Typically only a few pages made much use of it, and those were usually at the front of the book, or marking a major new section, for example the start of each gospel in a Gospel Book. In Western Europe the use of gold grounds on a large scale is mostly found either in the most sumptuous royal or imperial manuscripts in earlier periods such as Ottonian art, or towards the end of the Middle Ages, when gold became more widely available. The 14th-century Golden Haggadah in the British Library has a prefatory cycle of 14 miniatures of biblical subjects on gold ground tooled with a regular pattern, as was also typical in luxury Christian illumination at this period, as well as using gold letters for major headings.[45]

Gold was used in manuscripts in Persia, India and Tibet, for text, in miniatures and borders.[46] In Persia it was used as a background to text, typically with a plain "bubble" left around the letters. In Tibet, as well as China, Japan and Burma, it was used to form the letters or characters of the text, in all cases for especially important or luxurious manuscripts, usually of Buddhist texts, and often using paper dyed blue for a good contrast. In Tibet it became, relatively late, used as a background colour for images, restricted to some subjects only.[47] In India it was mostly used in borders, or in elements of images, such as the sky; this is especially common in the showy style of Deccan painting. Mughal miniatures may have beautifully painted landscape and animal borders painted on gold on a background of a similar colour. Gold flecks might also be added during the making of the paper.[48]

Gallery

- Folio 117r of the Pericopes of Henry II, Reichenau, c. 1002 - 1012: the Angel on the Tomb

- Gelati Gospels, Georgia, 12th century. The Crucifixion.

- Persian miniature, Khusraw discovers Shirin bathing in a pool. The water is oxidized silver.

Notes

- ^ Nuechterlein, "The use of gold in luxury objects and pre-Eyckian Netherlandish painting"

- ^ Pächt, 140

- ^ Folda, xxiii–xxiv, xxv

- ^ Pächt, 140; Folda, xxv–xxvi, 15; chrysography is the subject of most of Folda's book

- ^ Barber, 114–119; Runciman, 37, 59, 104

- ^ Pächt, 140; Folda, 15 makes similar remarks.

- ^ Nygren, 15

- ^ Nuechterlein, "A brief overview of gilding techniques"; Meagher

- ^ Bustacchini, 53

- ^ Bustacchini, 55; Connor, 6

- ^ Bustacchini, 56

- ^ Nuechterlein, "A brief overview of gilding techniques"; Meagher

- ^ Nuechterlein, "A brief overview of gilding techniques"; Meagher

- ^ Nuechterlein, "A brief overview of gilding techniques"; Meagher

- ^ Gill, 64

- ^ Pächt, 140–141, 140 quoted

- ^ Fuchs, 114–119; Saha, 22–23; Gill, 64–66

- ^ Pächt, 141

- ^ Bent, George R., "Lorenzo Monaco", Britannica.com, accessed 7 April 2021

- ^ Nuechterlein, "The use of gold in luxury objects and pre-Eyckian Netherlandish painting"

- ^ Nuechterlein, "From gold grounds to depicted space".

- ^ Nagel, Alexander, and Wood, Christopher S., Anachronic Renaissance, pp 323–324, 2020, Zone Books, MIT Press, ISBN 9781942130345, google books

- ^ Wright, 57–59, 62–66

- ^ "Salvator Mundi", Louvre page (in French): "signe d’archaïsme à la Van Eyck, rare chez Van Cleve et inconnu de ses copistes".

- ^ Nagel & Wood, 13–14; the painting

- ^ Drandaki, Anastasia (2014). A Maniera Greca: Content, Context and Transformation of a Term" Studies in Iconography Volume 35. Princeton, New Jersey: Index of Christian Art, Princeton University. pp. 39–72.

- ^ Hatzidakis, Manolis (1987). Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450–1830). Τόμος 1: Αβέρκιος – Ιωσήφ [Greek Painters after the Fall of Constantinople (1450–1830). Volume 1: Averkios – Iosif]. Athens: Center for Modern Greek Studies, National Research Foundation. pp. 241–251. hdl:10442/14844. ISBN 960-7916-01-8.

- ^ Tselenti-Papadopoulou, Niki G. (2002). Οι Εικονες της Ελληνικης Αδελφοτητας της Βενετιας απο το 16ο εως το Πρωτο Μισο του 20ου Αιωνα: Αρχειακη Τεκμηριωση [The Icons of the Greek Brotherhood of Venice from 1600 to the First Half of the 20th Century] (PDF). Athens: Ministry of Culture Publication of the Archaeological Bulletin No. 81. pp. 199–200. ISBN 960-214-221-9.

- ^ Katselakì, Andromache (1999). Εικόνα Παναγίας Γλυκοφιλούσας από την Κεφαλονιά στο Βυζαντινό Μουσείο [An Icon of the Panagia Glykophilousa from Kephalonia in the Byzantine Museum]. Athens: Journal of the Christian Archaeological Society ChAE 20 Period Delta. p. 380.

- ^ Egerton, Judy, National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The British School, 243–244, 1998, ISBN 1857091701

- ^ Sotheby's, "Master Paintings & Sculpture Part I", 28 January 2021, New York, online (see "Catalogue Note"

- ^ Nelson, 15 (quoted)

- ^ Richman-Abdou; Nelson, 15–18

- ^ Momoyama, 2–3, #s 7, 9, 15, 24, 25, 26; Stanley-Baker, 141–143; Mymet

- ^ Stanley-Baker, 141

- ^ for example in Momoyama, # 28

- ^ Department of Asian Art (October 2003). "Rinpa Painting Style". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ Momoyama, #s 4, 6, 11

- ^ Momoyama, # 10

- ^ Connor, 5–7

- ^ Runciman, 27

- ^ Connor, 8; Runciman, 27–29

- ^ Connor, 8 and Chapter 2; Runciman, 48–49, 66–73, 128, 107 for the traditional view; this view is challenged forcefully by Liz James in her "Introduction" (also Robin Cormack).

- ^ Gill, 54

- ^ Tahan, Ilana, The Golden Haggadah (Treasures in Focus), 5, 2011, British Library, ISBN 9780712358125

- ^ Saha, 22

- ^ Jana Igunma, San San May, Burkhard Quessel, "Illuminated Buddhist Manuscripts", 2019, British Library

- ^ Saha, 22–23

References

- Barber, Charles. "Out of Sight: Painting and Perception in Fourteenth-Century Byzantium". Studies in Iconography, vol. 35, 2014, pp. 107–120, JSTOR

- Bustacchini, G., Gold in mosaic art and technique, 1973, Gold Bulletin, 6, No . 2, pp . 52 – 56, Online pdf

- Connor, Carolyn Loessel, Saints and Spectacle: Byzantine Mosaics in Their Cultural Setting, 2016, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780190457624, 0190457627, google books

- Folda, Jaroslav, Byzantine Art and Italian Panel Painting: The Virgin and Child Hodegetria and the Art of Chrysography, 2015, Cambridge University Press

- Fuchs, Robert, in: Gillian Fellows-Jensen, Peter Springborg (eds), Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 5: Proceedings of the Fifth International Seminar Held at the University of Copenhagen 19th–20th April 1999, 2000, Royal Library, Copenhagen, ISBN 9788770230766, 8770230765, google books

- "Getty": Getty Museum, "Gold-ground panel painting", 2019, Video and transcript

- Gill, D.M., Illuminated Manuscripts, 1996, Brockhamton Press, ISBN 1841861014

- Meagher, Jennifer. "Italian Painting of the Later Middle Ages", 2010, In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, online

- "Momoyama": Momoyama, Japanese Art in the Age of Grandeur, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

- "Mymet", "Why Artists Use Gold Leaf and How You Can Make Your Own Ethereal Paintings", Kelly Richman-Abdou, 1 March 2018

- Nagel, Alexander, and Wood, Christopher S., Anachronic Renaissance, 2020, Zone Books, MIT Press, ISBN 9781942130345, google books

- Nelson, Robert S., "Modernism's Byzantium Byzantium's Modernism", Chapter 1 in Betancourt, Roland; Taroutina, Maria (eds.).Byzantium/Modernism: The Byzantine as Method in Modernity, BRILL, Leiden, ISBN 9789004300019, google books

- Nygren, Barnaby. "We first pretend to stand at a certain window': Window as Pictorial Device and Metaphor in the Paintings of Filippo Lippi". Notes in the History of Art, vol. 26, no. 1, 2006, pp. 15–21, JSTOR

- Nuechterlein, Jeanne, "From Medieval to Modern: Gold and the Value of Representation in Early Netherlandish Painting", 2013, University of York, Department of History of Art, History of Art Research Portal, online (or PDF) – individual PDF page titles used, see first page.

- Pächt, Otto, Book Illumination in the Middle Ages (trans fr German), 1986, Harvey Miller Publishers, London, ISBN 0199210608

- Pencheva, Bissera V, The Sensual Icon: Space, Ritual and the Senses in Byzantium, 2010, Penn State Press, google books

- Richman-Abdou, Kelly, "The Splendid History of Gustav Klimt’s Glistening “Golden Phase”", Mymet, 16 September 2018

- Steven Runciman, Byzantine Style and Civilization, 1975, Penguin

- Saha, Anindita Kundu, The Conservation of Endangered Archives and Management of Manuscripts in Indian Repositories, 22–23, 2020, Cambridge Scholars Publisher, ISBN 9781527560901, 1527560902, google books

- Stanley-Baker, Joan, Japanese Art, 2000 (2nd edn), Thames and Hudson, World of Art, ISBN 0500203261

- Wright, Alison, "Crivelli's Divine Materials" (pdf) in Ornament & illusion : Carlo Crivelli of Venice, 2015, Paul Holberton Publishing / Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, ISBN 9781907372865