Giant mouse lemur

| Giant mouse lemur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Northern giant mouse lemur (M. zaza) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | Cheirogaleidae |

| Genus: | Mirza J. E. Gray, 1870 |

| Type species | |

| Cheirogalus coquereli A. Grandidier, 1867 | |

| Species | |

| |

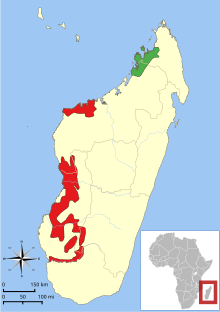

| Distribution of Mirza: | |

The giant mouse lemurs are members of the strepsirrhine primate genus Mirza. Two species have been formally described; the northern giant mouse lemur (Mirza zaza) and Coquerel's giant mouse lemur (Mirza coquereli). Like all other lemurs, they are native to Madagascar, where they are found in the western dry deciduous forests and further to the north in the Sambirano Valley and Sahamalaza Peninsula. First described in 1867 as a single species, they were grouped with mouse lemurs and dwarf lemurs. In 1870, British zoologist John Edward Gray assigned them to their own genus, Mirza. The classification was not widely accepted until the 1990s, which followed the revival of the genus by American paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall in 1982. In 2005, the northern population was declared a new species, and in 2010, the World Wide Fund for Nature announced that a southwestern population might also be a new species.

Giant mouse lemurs are about three times larger than mouse lemurs, weighing approximately 300 g (11 oz), and have a long, bushy tail. They are most closely related to mouse lemurs within Cheirogaleidae, a family of small, nocturnal lemurs. Giant mouse lemurs sleep in nests during the day and forage alone at night for fruit, tree gum, insects, and small vertebrates. Unlike many other cheirogaleids, they do not enter a state of torpor during the dry season. The northern species is generally more social than the southern species, particularly when nesting, though males and females may form pair bonds. The northern species also has the largest testicle size relative to its body size among all primates and is atypical among lemurs for breeding year-round instead of seasonally. Home ranges often overlap, with related females living closely together while males disperse. Giant mouse lemurs are vocal, although they also scent mark using saliva, urine, and secretions from the anogenital scent gland.

Predators of giant mouse lemurs include the Madagascar buzzard, Madagascar owl, fossa, and the narrow-striped mongoose. Giant mouse lemurs reproduce once a year, with two offspring born after a 90-day gestation. Babies are initially left in the nest while the mother forages, but are later carried by mouth and parked in vegetation while she forages nearby. In captivity, giant mouse lemurs will breed year-round. Their lifespan in the wild is thought to be five to six years. Both species are listed as endangered due to habitat destruction and hunting. Like all lemurs, they are protected under CITES Appendix I, which prohibits commercial trade. Despite breeding easily, they are rarely kept in captivity. The Duke Lemur Center coordinated the captive breeding of an imported collection of the northern species, which rose from six individuals in 1982 to 62 individuals by 1989, but the population fell to six by 2009 and was no longer considered a breeding population.

Taxonomy

The first species of giant mouse lemur was described by the French naturalist Alfred Grandidier in 1867 based on seven individuals he had collected near Morondava in southwestern Madagascar. Of these seven specimens, the lectotype was selected in 1939 as MNHN 1867–603, an adult skull and skin. Naming the species after the French entomologist Charles Coquerel,[4] Grandidier placed Coquerel's giant mouse lemur (M. coquereli) with the dwarf lemurs in the genus Cheirogaleus (which he spelled Cheirogalus) as C. coquereli. He selected this generic assignment based on similarities with fork-marked lemurs (Phaner), which he considered to also be members of Cheirogaleus. The following year, the German naturalist Hermann Schlegel and Dutch naturalist François Pollen independently described the same species and coincidentally gave it the same specific name, coquereli, basing theirs on an individual from around the Bay of Ampasindava in northern Madagascar. Unlike Grandidier, they placed their specimen in the genus Microcebus (mouse lemurs); however, these authors also listed all Cheirogaleus under Microcebus and based the classification of their species on similarities with the greater dwarf lemur (M. typicus, now C. major).[5]

In 1870, the British zoologist John Edward Gray placed Coquerel's giant mouse lemur into its own genus, Mirza. This classification was widely ignored and later rejected in the early 1930s by zoologists Ernst Schwarz, Guillaume Grandidier, and others, who felt that its longer fur and bushy tail did not merit a separate genus and instead placed it in Microcebus.[6] British anatomist William Charles Osman Hill also favored this view in 1953, noting that despite its larger size (comparable to Cheirogaleus), its first upper premolar was proportionally small as in Microcebus.[7] In 1977, French zoologist Jean-Jacques Petter also favored the Microcebus classification, despite the threefold size difference between Coquerel's giant mouse lemur and the other members of the genus.[8]

The genus Mirza was resurrected in 1982 by American paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall[5][8][9] to represent an intermediate branch between Microcebus and Cheirogaleus,[5] citing the Coquerel's giant mouse lemur's significantly larger size than the largest Microcebus and locomotor behavior more closely aligned with Cheirogaleus.[5][8] Adoption of Mirza was slow,[10] though in 1994 it was used in the first edition of Lemurs of Madagascar by Conservation International.[11][12] In 1993, primatologist Colin Groves initially favored the Microcebus classification in the second edition of Mammal Species of the World,[11] but began supporting the resurrection of Mirza in 2001.[8][13] In 1991, prior to adopting Mirza, Groves was the first to use the common name "giant mouse lemur". Prior to that, they were popularly referred to as "Coquerel's mouse lemur".[14]

In 2005, Peter M. Kappeler and Christian Roos described a new species of giant mouse lemur, the northern giant mouse lemur (M. zaza).[8][15] Their studies compared the morphology, behavioral ecology, and mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences of specimens from both Kirindy Forest in central-western Madagascar and around Ambato in northwestern Madagascar,[8][15] part of the Sambirano valley.[8] Their study demonstrated distinct differences in size, sociality, and breeding, as well as sufficient genetic distance to merit specific distinction between the northern and central-western populations. Because Grandidier's description was based on a southern specimen, they named the northern population as a new species.[15]

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) announced in 2010 that a biodiversity study from 2009 in the gallery forest of Ranobe near Toliara in southwestern Madagascar revealed a population of giant mouse lemurs previously unknown to science, and possibly a new species. They noted a significant difference in coloration between the two known species and the specimen they observed. However, further testing was required to confirm the discovery.[16]

Etymology

| Competing phylogenies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mirza, Microcebus, and Allocebus form a clade within Cheirogaleidae, regardless of whether Phaner is a sister group (top—Weisrock et al. 2012)[17] or more closely related to Lepilemur (bottom—Masters et al. 2013).[18] |

The etymology of Mirza puzzled researchers for many years. Gray often created mysterious and unexplained taxonomic names—a trend continued with his description of not only Mirza in 1870, but also the genera Phaner (fork-marked lemurs) and Azema (for M. rufus, now a synonym for Microcebus), both of which were described in the same publication. In 1904, American zoologist Theodore Sherman Palmer attempted to document the etymologies of all mammalian taxa, but could not definitively explain these three genera. For Mirza, Palmer only noted that it derived from the Persian title mîrzâ ("prince"), a view tentatively supported by Alex Dunkel, Jelle Zijlstra, and Groves in 2012. However, because the reference to Persian princes might have come from Arabian Nights, a popular piece of literature at the time, Dunkel et al. also searched the general literature published around 1870. The origin of all three names was found in a British comedy The Palace of Truth by W. S. Gilbert, which premiered in London on 19 November 1870, nearly one and a half weeks prior to the date written on the preface of Gray's manuscript (also published in London). The comedy featured characters bearing all three names: King Phanor (sic), Mirza, and Azema. The authors concluded that Gray had seen the comedy and then based the names of three lemur genera on its characters.[19]

Evolution

Based on studies using morphology, immunology, repetitive DNA, SINE analysis, multilocus phylogenetic tests,[17] and mitochondrial genes (mtDNA),[20] giant mouse lemurs are most closely related to mouse lemurs within the family Cheirogaleidae, and together they form a clade with the hairy-eared dwarf lemur (Allocebus). Both dwarf lemurs and fork-marked lemurs are more distantly related,[17][18][21] with fork-marked lemurs being either a sister group of all cheirogaleids,[17][21] or more closely related to sportive lemurs (Lepilemur).[18]

Although Mirza, Microcebus, and Allocebus form a clade within Cheirogaleidae, the three lineages are thought to have diverged during a narrow window of time, so the relationships within this clade are difficult to determine and may change with further research.[22] All three are thought to have diverged at least 20 mya (million years ago),[18] although another estimate using mtDNA places the divergence between Mirza and Microcebus at 24.2 mya. Divergence between the two recognized species of giant mouse lemur is estimated at 2.1 mya.[23]

Description

Though giant mouse lemurs are relatively small cheirogaleids,[9] they are more than three times larger than the smallest members of the family, the mouse lemurs.[8] Their body weight averages 300 g (11 oz).[8][9] At around 300 mm (12 in), their bushy and long tail is longer than their head-body length, which averages 233 mm (9.2 in).[9] Their forelimbs are shorter than the hind limbs (with an intermembral index of 70), a trait shared with mouse lemurs.[24] The skull is similar to that of dwarf and mouse lemurs,[25] and the auditory bullae are small.[26]

Like other cheirogaleids, the dental formula for giant mouse lemurs is 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 × 2 = 36; on each side of the mouth, top and bottom, there are two incisors, one canine, three premolars, and three molars—a total of 36 teeth.[27] Their upper teeth converge towards the front of the mouth, but are straighter than those in mouse lemurs.[26] The first upper premolar (P2) is relatively small, but nearly as tall as the next premolar (P3). Unlike mouse lemurs and more like dwarf lemurs, giant mouse lemurs have a prominent anterior lower premolar (P2). Also more aligned with dwarf lemurs, the first two upper molars (M1–2) have a more anterior hypocone that sits opposite the metacone, compared to the mouse lemurs' more posterior hypocone, which is presumably a symplesiomorphic (ancestral) trait.[25] Also on M1 and M2, the cingulum (a crest or ridge on the tongue side) comprises two small cuspules.[26] In all other dental characteristics, giant mouse lemurs are noticeably similar to both dwarf and mouse lemurs.[25]

Giant mouse lemurs have two pairs of mammae, one on the chest (pectoral) and one on the abdomen (abdominal).[28] Their fur is typically grayish-brown on the dorsal (back) side and more gray in color on the ventral (front) side.[9][29] The tail is typically black-tipped.[9] The new population found by WWF in 2010 has an overall lighter color, along with reddish or rusty patches near the hands and feet on the dorsal side of the arms and legs. This population also has a red tail, which darkens at the end.[16] Vibrissae are found above the eyes (superciliary), above the mouth (buccal), under the lower jaw (genal), near the top of the jaw (interramal), and on the wrist (carpal).[30] Like mouse lemurs, the ears are large and membranous.[31]

Ear size is one differentiating factor between the northern giant mouse lemur and Coquerel's giant mouse lemur, with the former having shorter, rounded ears,[29] while the latter has relatively large ears.[9] The northern giant mouse lemur is generally larger and also has a shorter tail and shorter canine teeth.[29] This species also has the largest testicles relative to body size of any living primate, with an average volume of 15.48 cm3 (0.945 cu in),[32][33] corresponding to 5.5% of its body weight. If human males had comparably sized testes, they would weigh 4 kg (8.8 lb) and be the size of a grapefruit.[33]

Distribution and habitat

Coquerel's giant mouse lemur has a spotty distribution across western Madagascar's dry deciduous forests due to the forest fragmentation throughout the region.[34] The dry forests in this lowland region vary in elevation from sea level to 700 m (2,300 ft).[2][34] The range of this species is divided into northern and southern subpopulations,[2] which are separated by several hundred kilometers. Both historical and current populations between these ranges are uncertain.[9] The southern region is bound by the Onilahy River in the south and the Tsiribihina River in the north, while the northern population is found in the northwestern corner of the island at Tsingy de Namoroka National Park.[2][34][35] They are most commonly found in forests near rivers and ponds.[11][36]

The northern giant mouse lemur is found in isolated forest patches along the northwest coast[37] in both the more humid Sambirano valley[2][36] and Sahamalaza Peninsula, as well as the Ampasindava Peninsula.[3] Its range extends from the Maeverano River in the south to the Mahavavy River in the north.[37] The new population reported by the WWF in 2010 is found in the gallery forests of Ranobe near Toliara in southwestern Madagascar.[16]

Behavior

Giant mouse lemurs were first studied in the wild by Petter and colleagues in 1971.[9][38] His observations were secondary to his primary research interest, the fork-marked lemurs north of Morondava. Both northern and southern populations were studied intermittently between 1978 and 1981, and in 1993, long-term social and genetic studies began in Kirindy Forest. Behavioral studies of captive individuals have also been performed at the Duke Lemur Center (DLC) in Durham, North Carolina during the 1990s.[9]

Population density and territory

Before the recognition of more than one species, differences in population density were noted between southern forests like Kirindy and northern forests near Ambanja.[9] Later, it was recognized that Coquerel's giant mouse lemur was found in lower densities than the northern giant mouse lemur.[39] The former range between 30 and 210 individuals per square kilometer (250 acres),[40] with lower densities in open areas of the forest,[9] while the latter has been recorded with 385 to 1,086 individuals per km2. However, in the case of the northern giant mouse lemur, populations were found in more isolated forest fragments and it is thought that their consumption of introduced cashew and mango help sustain these higher populations.[39]

According to studies of Coquerel's giant mouse lemur, home ranges of both sexes vary from 1 to 4 hectares (2 to 10 acres) with frequent overlap,[40][41][42] particularly on the periphery of their range.[43] Individuals most heavily use and aggressively defend a smaller core area within their range.[40][43] Individuals can have up to eight neighbors.[41] Home ranges of males tend to overlap with those of both females and other males,[40] and typically expand to four times the size during the mating season.[40][41] Female home ranges show no variability in size, and can remain stable for years. At Kirindy Forest, genetic studies showed that the home ranges of related females tend to clump closely together, while unrelated males may overlap their range, suggesting male dispersal and migration is responsible for gene flow.[41]

Activity patterns

Both species are strictly nocturnal,[9] leaving their nests around sunset to stretch and self-groom for a few minutes.[41][44][45] Both species typically forage between 5 and 10 m (16 and 33 ft) above the forest floor, though Coquerel's giant mouse lemur has been observed on the ground.[44] They primarily move by quadrupedal running and occasionally leaping between branches, and use the same feeding postures as mouse lemurs, such as clinging to tree trunks.[42] When moving through the trees, giant mouse lemurs scurry rapidly like mouse lemurs, unlike dwarf lemurs, which use more deliberate movement.[25] Slow movements are usually seen in lower, denser foliage when hunting for insects, while more rapid motion and leaping is typically seen at moderate heights of 2–5 m (6.6–16 ft). Surveillance of the home range involves slower movements in lighter foliage near the tops of large trees, while movements along the border of a home range is more rapid and occurs at a lower height. Similar movement patterns have been observed in captivity as well.[46]

Giant mouse lemurs begin foraging moments before the sun disappears,[41] occasionally participate in social activities during the last half of the night,[44][46] and return to one of their nests prior to sunrise.[41] Cold temperatures cause them to leave the nest later and return early, sometime during the second half of the night.[41][44][45] During the first half of the night, giant mouse lemurs are more likely to rest for an hour or more, usually at the expense of social activities, but not feeding time. Rest periods are longer when temperatures are low.[45] Unlike many other cheirogaleids, they remain active all year and do not enter daily or seasonal torpor.[41][44][42]

Nesting

Both species sleep in round nests up to 50 cm (20 in) across made of interlaced lianas, branches, leaves, and twigs gathered from nearby trees and woven using the mouth and hands. Nests are typically between 2 and 10 m (6.6 and 33 ft) above the ground in the fork of large tree branches or surrounded by dense lianas.[45][47][48] Trees covered in thick lianas as well as trees with year-round leaf cover (e.g. Euphorbiaceae) are favored for nest construction, though large bare trees may be used by building the nest higher.[45] In addition to nesting in dense lianas, individual giant mouse lemurs will rotate between 10 and 12 nests every few days to avoid predators.[47][48] Only females have been observed building nests in the wild,[48] though males, females, and young have been observed building nests in captivity.[45] Multiple nests are sometimes built in the same tree or in nearby trees and are shared by neighboring giant mouse lemurs, fork-marked lemurs, and the introduced black rat (Rattus rattus). Unlike most other nocturnal lemurs, giant mouse lemurs do not appear to sleep in tree holes.[48]

Social structure

Both species usually are solitary foragers,[41][47][49] although the northern giant mouse lemur tends to be the most social, possibly due to its higher population density.[50] Up to eight (typically four) adult males, adult females, and juveniles may be found in a northern giant mouse lemur nest,[15][41][51] whereas Coquerel's giant mouse lemurs do not nest communally, except when females share their nest with their offspring.[41][47] Males do groom and call to females when they come into contact, and according to radio-tracking and direct observations at Analabe near Kirindy, they form pair bonds,[41] sometimes briefly traveling together during the dry season.[40] However, most interactions between adults are infrequent and typically occur later at night and particularly during the dry season in overlapping core areas, often involving chases and other agonistic behavior, and only rarely social grooming.[42][52] During the mating season, males act aggressively towards one another, pulling out fur around the head and shoulders and biting the head.[52]

Giant mouse lemurs use at least eight vocalizations, the most common of which are contact calls, which sound like "hum" or a "hein" and are used when moving and when meeting familiar individuals. A "mother-infant meeting call" used at dawn before returning to the nest consists of short, modulated whistles. Both males and females have distinct single note calls used in territorial behavior; the female call sounds like "pfiou" and the male call is a short, loud whistle. Both sexes use an alarm call, which sounds like a "croak", and an agonistic call, which consists of repeated "tisk-tisk-tisk" sounds.[53] Females exhibit a "waking call sequence",[54] sometimes referred to as "loud calls", which start when foraging commences and then switch to quieter "hon" calls possibly to indicate their position to their neighbors.[44][52][54] A long "sexual call sequence" consisting of soft whistle and several modulated, hoarse "brroak" calls is used by both sexes during estrus.[54] Studies of captive individuals have found other vocalizations, but their purpose has not been determined.[52] The northern giant mouse lemur appears to be the most vocal of the two species.[50] Although vocalizations are the primary form of social communication,[52] they also scent mark using saliva, urine, and secretions from the anogenital scent gland on small branches and other objects.[44][52]

Reproduction

Reproduction starts in November for Coquerel's giant mouse lemur at Kirindy Forest;[44] the estrous cycle runs approximately 22 days, while estrus lasts only a day or less.[11] The mating season in this southern population is limited to a few weeks, whereas the northern giant mouse lemur is thought to breed throughout the year, a trend seen in only two other species of lemur: the aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis) and the red-bellied lemur (Eulemur rubriventer).[32] The northern giant mouse lemur had been observed breeding year-round in captivity if their litter did not survive or was removed,[11] but at the time this population was thought to be Coquerel's giant mouse lemur.[32]

One to three offspring (typically two) are born after 90 days of gestation,[41][42][44] weighing approximately 12 g (0.42 oz). Because they are poorly developed, they initially remain in their mother's nest for up to three weeks, being transported by mouth between nests.[41][42] Once they have grown sufficiently, typically after three weeks, the mother will park her offspring in vegetation while she forages nearby.[41][44] After a month, the young begin to participate in social play and grooming with their mother, and between the first and second month, young males begin to exhibit early sexual behaviors (including mounting, neck biting, and pelvic thrusting).[55] By the third month, the young forage independently, though they maintain vocal contact with their mother[41][44][55] and use a small part of her range.[55]

Females start reproducing after ten months, while males develop functional testicles by their second mating season.[41] Testicle size in the northern giant mouse lemur does not appear to fluctuate by season,[32] and is so large relative to the animal's body mass that it is the highest among all primates.[41][32] This emphasis on sperm production in males, as well as the use of copulatory plugs, suggests a mating system best described as polygynandrous[32] where males use scramble competition (roaming widely to find many females).[42][32] In contrast, male Coquerel's giant mouse lemurs appear to fight for access to females (contest competition) during their breeding season.[32] Males disperse from their natal range, and the age at which they leave varies from two years to several. Females reproduce every year, although postpartum estrus has been observed in captivity. In the wild, the lifespan of giant mouse lemurs is thought to rarely exceed five or six years,[41] though in captivity they can live up to 15 years.[11]

Ecology

Both species are omnivorous, eating fruit, flowers, buds, insect excretions, tree gums, large insects, spiders, frogs, chameleons, snakes, small birds,[41][42][44] and eggs.[56] Coquerel's giant mouse lemur is thought to opportunistically prey on mouse lemurs[41][44] after an individual was found with a half-eaten gray mouse lemur (M. murinus) in a trap.[57] During June and July, at the peak of the dry season, this species relies on sugary excretions from the larvae of hemipteran and cochineal insects as well as tree gums.[41][44] The sugary excretions are obtained by either licking them from the back of the insect or collecting the crystallized sugars that accumulate beneath the insect colony.[56] During this time of year, feeding on insect secretions can account for 60% of feeding activity.[42] In contrast, the northern giant mouse lemur relies on cashew fruits during the dry season.[50]

Giant mouse lemurs are often sympatric with mouse lemurs, such as M. murinus, though they are typically found higher in the canopy and favor thicker, taller gallery forests.[42] At the Marosalaza forest (north of Morondava), Coquerel's giant mouse lemur is sympatric with four other nocturnal lemurs (mouse lemurs, sportive lemurs, dwarf lemurs, and fork-marked lemurs), but manages niche differentiation by feeding at different times and specializing on insect secretions during the dry season.[58]

Diurnal birds of prey such as the Madagascar buzzard (Buteo brachypterus) are their most significant predators. Other documented predators of giant mouse lemurs include the fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox), Madagascar owl (Asio madagascariensis), and the narrow-striped mongoose (Mungotictis decemlineata).[59]

Conservation

In 2012, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) assessed both Coquerel's giant mouse lemur and the northern giant mouse lemur as endangered. Prior to that, both species had been listed as vulnerable. Populations of both species are in decline due to habitat destruction, primarily for slash-and-burn agriculture and charcoal production. Also, they are both hunted for bushmeat.[2][3] The population announced by the WWF in 2010 was found outside the limits of a nearby protected area, PK32-Ranobe, which was granted temporary protection status in December 2008 and is co-managed by the WWF. Its forests were not included in the protected area due to existing concessions for mining activities.[16]

As with all lemurs, giant mouse lemurs were first protected in 1969 when they were listed as "Class A" of the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. This prohibited hunting and capture without authorization, which would be given only for scientific purposes or the national interest. In 1973, they were also protected under CITES Appendix I, which strictly regulates their trade and forbids commercial trade. Although enforcement is patchy, they are also protected under Malagasy law.[10]

Giant mouse lemurs are rarely kept in captivity, though they breed easily. In 1989, the Duke Lemur Center held more than 70% of the captive population (45 of 62 individuals). At the time, the DLC was coordinating a captive breeding program for Coquerel's giant mouse lemur, and all individuals kept at American facilities were descended from six individuals imported by the DLC in 1982[10] from the region around Ambanja.[9] As of 2009 the International Species Information System (ISIS) recorded only six remaining individuals registered in the United States and Europe, all reclassified as northern giant mouse lemurs and considered a non-breeding population;[44] in 2015 only a single female remained on record.[60]

References

Citations

- ^ "Checklist of CITES Species". CITES. UNEP-WCMC. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Andriaholinirina, N.; et al. (2012). "Mirza coquereli". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Andriaholinirina, N.; et al. (2012). "Mirza zaza". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Beolens, Watkins & Grayson 2009, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b c d Tattersall 1982, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Osman Hill 1953, p. 325.

- ^ Osman Hill 1953, p. 333.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mittermeier et al. 2010, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kappeler 2003, p. 1316.

- ^ a b c Harcourt 1990, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f Nowak 1999, p. 67.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 1994, p. 80.

- ^ Groves 2001, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Dunkel, Zijlstra & Groves 2012, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Kappeler et al. 2005, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d "New population of rare giant-mouse lemurs found in Madagascar". World Wildlife Fund. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d Weisrock et al. 2012, p. 1626.

- ^ a b c d Masters et al. 2013, p. 209.

- ^ Dunkel, Zijlstra & Groves 2012, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Masters et al. 2013, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b Roos, Schmitz & Zischler 2004, p. 10653.

- ^ Weisrock et al. 2012, pp. 1627–1628.

- ^ Kappeler et al. 2005, p. 15.

- ^ Fleagle 2013, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c d Tattersall 1982, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Groves 2001, p. 70.

- ^ Swindler 2002, p. 73.

- ^ Tattersall 1982, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Kappeler et al. 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Tattersall 1982, p. 129.

- ^ Fleagle 2013, pp. 60–62.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rode-Margono et al. 2015.

- ^ a b Walker, M. (3 July 2015). "Lemur found with giant testicles". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2015-07-09. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Mittermeier et al. 2010, p. 164.

- ^ Markolf, Kappeler & Rasoloarison 2008, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Harcourt 1990, p. 45.

- ^ a b Markolf, Kappeler & Rasoloarison 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Pages 1980, p. 97.

- ^ a b Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 168–170.

- ^ a b c d e f Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Kappeler 2003, p. 1317.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fleagle 2013, p. 62.

- ^ a b Harcourt 1990, p. 46.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Mittermeier et al. 2010, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e f Pages 1980, p. 101.

- ^ a b Pages 1980, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d Mittermeier et al. 2010, p. 166.

- ^ a b c d Kappeler 2003, pp. 1316–1317.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2010, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Mittermeier et al. 2010, p. 171.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b c d e f Kappeler 2003, p. 1318.

- ^ Pages 1980, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Pages 1980, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b c Pages 1980, p. 112.

- ^ a b Pages 1980, p. 98.

- ^ Goodman 2003, p. 1222.

- ^ Pages 1980, p. 115.

- ^ Goodman 2003, pp. 1222–1223.

- ^ Species holding report for: Mirza / Mouse lemur (Report). International Species Information System (ISIS). 2015.

Literature cited

- Beolens, B.; Watkins, M.; Grayson, M. (2009). The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9304-9. OCLC 270129903.

- Dunkel, A.R.; Zijlstra, J.S.; Groves, C.P. (2012). "Giant rabbits, marmosets, and British comedies: etymology of lemur names, part 1" (PDF). Lemur News. 16: 64–70. ISSN 1608-1439. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

- Fleagle, J.G. (2013). Primate Adaptation and Evolution (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-378632-6. OCLC 820107187.

- Goodman, S.M. (2003). "Predation on lemurs". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1221–1228. ISBN 978-0-226-30306-2. OCLC 51447871.

- Groves, C.P. (2001). Primate Taxonomy. Smithsonian. ISBN 978-1-56098-872-4. OCLC 44868886.

- Harcourt, C. (1990). Thornback, J (ed.). Lemurs of Madagascar and the Comoros: The IUCN Red Data Book (PDF). World Conservation Union. ISBN 978-2-88032-957-0. OCLC 28425691.

- Kappeler, P.M. (2003). "Mirza coquereli, Coquerel's Dwarf Lemur". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1316–1318. ISBN 978-0-226-30306-2. OCLC 51447871.

- Kappeler, P.M.; Rasoloarison, R.M.; Razafimanantsoa, L.; Walter, L.; Roos, C. (2005). "Morphology, behaviour and molecular evolution of giant mouse lemurs (Mirza spp.) Gray 1870, with description of a new species" (PDF). Primate Report. 71: 3–26.

- Markolf, M.; Kappeler, P.M.; Rasoloarison, R. (2008). "Distribution and conservation status of Mirza zaza" (PDF). Lemur News. 13: 37–40. ISSN 1608-1439.

- Masters, J. C.; Silvestro, D.; Génin, F.; DelPero, M. (2013). "Seeing the wood through the trees: The current state of higher systematics in the Strepsirhini" (PDF). Folia Primatologica. 84 (3–5): 201–219. doi:10.1159/000353179. hdl:2318/140024. PMID 23880733.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Tattersall, I.; Konstant, W.R.; Meyers, D.M.; Mast, R.B. (1994). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (1st ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 1-881173-08-9. OCLC 32480729.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Louis, E.E.; Richardson, M.; Schwitzer, C.; et al. (2010). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (3rd ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 978-1-934151-23-5. OCLC 670545286.

- Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Osman Hill, W.C. (1953). Primates Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy I – Strepsirhini. Edinburgh Univ Pubs Science & Maths, No 3. Edinburgh University Press. OCLC 500576914.

- Pages, E. (1980). "Ethoecology of Microcebus coquereli during the dry season". In Charles-Dominique, P.; Cooper, H.M.; Hladik, A.; Hladik, C.M.; Pages, E.; Pariente, G.F.; Petter-Rousseaux, A.; Schilling, A.; Petter, J.J. (eds.). Nocturnal Malagasy Primates: Ecology, Physiology, and Behavior. Academic Press. pp. 97–116. ISBN 978-0-323-15971-5. OCLC 875506676.

- Rode-Margono, E.J.; Nekaris, K.; Kappeler, P.M.; Schwitzer, C. (2015). "The largest relative testis size among primates and aseasonal reproduction in a nocturnal lemur, Mirza zaza". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 158 (1): 165–169. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22773. PMID 26119092.

- Roos, C.; Schmitz, J.; Zischler, H. (2004). "Primate jumping genes elucidate strepsirrhine phylogeny". PNAS. 101 (29): 10650–10654. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110650R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403852101. PMC 489989. PMID 15249661.

- Swindler, D.R. (2002). Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-43150-7. OCLC 70728410.

- Tattersall, I. (1982). The Primates of Madagascar. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-04704-3. OCLC 7837781.

- Weisrock, D.W.; Smith, S.D.; Chan, L.M.; Biebouw, K.; Kappeler, P.M.; Yoder, A.D. (2012). "Concatenation and concordance in the reconstruction of mouse lemur phylogeny: An empirical demonstration of the effect of allele sampling in phylogenetics". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (6): 1615–1630. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss008. PMC 3351788. PMID 22319174.

External links

- Original description of Mirza by J.E. Gray, 1870 – Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Original description of C. coquereli by A. Grandidier, 1867 – Biodiversity Heritage Library (in French)

- Description of M. coquereli by Schlegel and Pollen, 1868 – Biodiversity Heritage Library (in French)