George Augustus Bennett

George Augustus Bennett | |

|---|---|

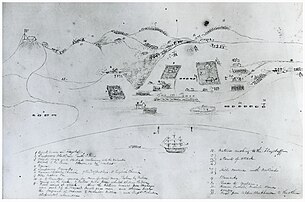

The New-Zealand Festival, 11 May 1844. Artist: Joseph Jenner Merrett[1] | |

| Born | 6 January 1807 |

| Died | 30 April 1845 (aged 38) Auckland, New Zealand[2] |

| Buried | Block E 45, Symonds Street Cemetery, Auckland (removed mid-1960s) |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Board of Ordnance |

| Years of service | 1827–1845 |

| Rank | 2nd Captain |

| Service number | 611 |

| Unit | Corps of Royal Engineers |

| Commands | Hill Drawing Department, Statistics and Antiquities, Ordnance Survey of Ireland, 1838– CRE, New Zealand, 1842–45 |

| Campaigns | Tauranga Campaign, 1842 (military works)[3]: 47–50 Flagstaff War, 1844–45 (military works) |

| Memorials | General Anglican Memorial, Symonds Street Cemetery |

| Relations | William James Early Bennett Frederick Hamilton Bennett |

Captain George Augustus Bennett (6 January 1807 – 30 April 1845) was an English military engineer of the Corps of Royal Engineers, Board of Ordnance.[4]: 25 He served in Corfu (1828–1832), on the Ordnance Survey of Ireland (1832–1841), as Commanding Royal Engineer in New Zealand (1842–1845) and first president of the Auckland Mechanics' Institute (1842–1845).[2] Whilst serving in Ireland he devised and implemented the system of contours for Ordnance Survey maps. In the Colony of New Zealand he designed the flagstaff blockhouse central to the Battle of Kororāreka (1845)[3]: 52–54 and other military works.[5]: 97

Early life

Bennett, born 6 January 1807, was the second of three sons of William Bennett of Portsea, Hampshire, a major in the Corps of Royal Engineers, and Mary Early.[6] William served at Fort Cumberland, Hampshire, and overseas at Nova Scotia commanding the 12th Company, Royal Sappers and Miners,[7]: 157 Sicily in 1810 and 1812–1815,[4]: 14 and Ireland, but died of consumption at Gosport, Hampshire, on or about 18 June 1821, aged 37 years. Mary married Major Thomas Alston Brandreth, RA, some years later, in 1826.[8]: 281 [9]

Paternal grandfather, George Augustus Bennett, had served as an officer of the Royal Marine Force; great-grandfather, William Bennett, attained the rank of rear admiral in the Royal Navy.[8]: 2 [10] Maternal grandfather, James Early, was an officer of the 1st Royal Garrison Battalion;[6] great-grandfather, Early, a farmer at Datchet, near Windsor, had been, by family legend, greatly in favour with George III on farming matters.[8]

Bennett was educated at Portora Royal School, Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, Ireland, for some of his early years.[11]: f14r His brother, Frederick, was born in Ireland in or about 1816. Carrying on a family line of military service[8]: 282–283 and profession of military engineer, he trained at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, from 1823 to 11 July 1827.

Breaking from family traditions, his brothers' callings were to the clergy, both taking their degrees at Christ Church, Oxford. William James Early Bennett, went on to make a remarkable contribution to the Oxford Movement.[8]: i

Career

Gentleman Cadet Bennett was commissioned as no. 611, 2nd lieutenant in the Corps of Royal Engineers, Board of Ordnance, at Woolwich, on 13 July 1827.[4]: 25 [12] He remained there for six months and, after a short leave, was posted to the Mediterranean.[13]

Corfu

In 1828, he was stationed at Corfu, Ionian Islands, where fortifications were being repaired and constructed by a company of Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners. As the works at Corfu were too extensive for the garrison there, a smaller fort to command the anchorage had been devised for the island of Vido, which, constructed from 1825, would be finished by 1831–32.[14]

Ireland

Ordnance Survey

In 1832 Bennett was assigned to the Ordnance survey of Ireland under command of Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Frederick Colby, RE, and Lieutenant Thomas Aiskew Larcom, RE, and advanced to rank of lieutenant on 10 December.[4]: 25 By the end of 1834 he'd worked through producing survey memoirs for many county Antrim, Down and Armagh parishes—Glenavy, Aghaderg, Annaclone, Clonallan, Donacloney, Donaghmore, Dromara, Dromore, Drumballyroney, Drumgath, Garvaghy, Magherally, Magheralin, Newry, Seapatrick, Shankill, Tullylish, Warrenpoint, Ballymore, Drumcree, Kilmore, Montiaghs, Seagoe—[15][16] and with Lieutenant Henry Tucker, RE, took charge of the operations in County Louth from about 1834.[17] Then, as Captain Robert Kearsley Dawson, RE, moved on to England in connection with the Reform Commission in 1835, Bennett took over his hill drawing role, superintending the hill-sketchers.[18]

Contours

On Sunday, 1 April 1838, Bennett gave 4th Division over to Lieutenant St George Lyster, RE, and took charge of the Hill-Drawing Department, Statistics and Antiquities; a change of scene that he hoped would restore his health after the pressures of divisional work. Colby and Larcom briefed him at Phoenix Park, Dublin, in 1–2 April. Larcom was keen to introduce light and shade into drawing hills and was attempting it on the rail road map. Colby revealed his scheme for heights of hills or elevation by a series of contours at 50 ft each having a darker shade near the hilltop, which Larcom thought noble but impractical. A French engraver's example with houses, woods and other features worked into the shade with good effect was also shown, but trees were not distinct and Bennett disliked it.[11]: f1

Hill sketching work was expensive and after years of experiments Colby had not then seen any mode of drawing hills on maps that was perfectly satisfactory.[19] Colby reported to the Inspector General of Fortifications, 6 May 1840:

In the Cadastral Map of Ireland the altitudes marked are extremely numerous, and afford great assistance to the sketchers; still this information alone does not enable them to perfect sketches for definite use. Captain Larcom suggested running contour lines instrumentally at certain distances, as affording accurate data to regulate the detorication of hills.[20]: 45

In pursuit of the definite and useful map, Larcom instigated contouring in 1838, with Bennett specifically tasked with perfecting and implementing the new system.[19][21]: 61 In mid-April, Bennett set the department's senior civil assistant, Charles Whybrow Ligar,[22]: 154 to making a scale model from card in 50 ft contour heights which, quickly done, worked well. Having taken an office-residence at Armagh in April 1838, and inspected the civilian sketchers' work from Dungannon to Coleraine and the Giant's Causeway, he resolved that for efficacy and economy, the Royal Sappers and Miners must do the contour work. Settling in Armagh in early May he noted: "got all right and comfortable—shall now set to work—head aches as bad nearly as ever with eternal flushings well it will end one way or another—" The headaches and sore eyes continued, nevertheless, he worked through the method of instrumental contours and by the end of May had made a scale skeleton model of "Bendradagh" in 50 ft contour heights, and soon after cast a plaster model of it. He wrote on 29 May:

I question whether if the contours are taken every 25 ft. above the sea by the instrument, there be anything left for the sketcher to do—It seems to me that these 25 ft contours put to the 1 inch scale will fill the sheet—If so, it becomes a matter of calculation, whether an active Sapper cannot contour with an instrument a square mile a day the present rate of sketching only—One most valuable desideratum for the improvement of the country & easily comprehended by all classes (the other only understood by initiated and useless "to the general"—These contours I think can also systematically be united with light and shade, a union of art and mechanism which would perfect & render simple what has hitherto been a system of hyeroglyphics.[11]: f11r

The model proved useful to the sappers and by 13 June Bennett noted that they seemed to be getting on well, that: "the contour system works excellently and I have no doubt of its ultimate success—we shall contour soon a square mile a day instrumentally. How immeasurably superior to the sketching".[11]: f15v Colby clarified the development of instrumental contouring in 1840:

The use of contour lines had often been proposed by the Continental writers, on military plans for fortifications, &c., but the extensive use of contours obtained by the aid of levelling instruments had never been tried, from an apprehension of the difficulty and expense of the operation. Lieutenant Bennett has tried them over a small part of the north of Ireland with great apparent success; the time and cost has been small compared with the result.[20]: 45

Similarly, Larcom reported to the Commissioners enquiring into the Ordnance Memoir of Ireland in July 1843, that: "contouring was introduced under the direction of Lieutenant Bennett with such energy and ability that the average cost of contouring different parts of Donegal and Louth amounted only to about 10s. a square mile, or a farthing per acre, which was an addition so small as to be quite justifiable."[21]: 61

Bennett's contour map work, 1838–1840, including Inishowen, County Donegal, were successful and well received. Specimens and models of the Donegal work were sent to Chatham to be used in the Royal Engineers training course. Colby moved to contour County Louth before Donegal was complete, but Bennett was moving on and the work passed to his successor,[22]: 115 who then turned all hill department draftsmen into contourers.[21]: 62

England

Royal Engineers, under command of Captain George Barney, RE, had been stationed in New South Wales, Australia, since 1835. From there, Lieutenant Henry Williamson Lugard, RE, and Clerk of Works George Graham had been assigned to New Zealand following the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. Whilst Bennett was at Woolwich, England, in early 1841, the Master General of the Ordnance appointed him to assume command of the engineer department in New Zealand. He and his dog embarked at Plymouth on the Lady Clarke for passage to New Zealand on 4 September 1841.[5]</ref>: 94 [11]: f42r [23]

New Zealand

Stopovers

The Lady Clarke arrived in Sydney, New South Wales, on 26 December 1841.[24] After sightseeing trips to Newcastle and the river to Maitland, to Sydney, Parramatta, Windsor and a brief stay with Sir George and Lady Gipps, then to Wollongong where the hills, forest and rivers to Campbelltown caught his eye for picturesque landscape,[11]: f68–f69 Bennett continued on to New Zealand by the brig Bristolian on 28 January 1842. He was joined by several passengers he'd met on the voyage out, a coach-maker and wife, James and Elizabeth Soall.[5]: 94 [25]

The Bristolian arrived at Kororāreka, Bay of Islands, on 15 February. With a little effort he located the non-existent towns of Victoria, and Russell, inspected Lugard's military works, then moved on to Auckland.[26][5]: 94

Fort Britomart and residence

Soon after his arrival in Auckland on 21 February, Governor William Hobson granted Ordnance an elevated Lot 1, Section 8, in front of Fort Britomart for the wooden Royal Engineer office-residence he'd shipped with him. Levelled by a strong gale during its construction on 18 March, Bennett rebuilt it in local brick, positioned with a picturesque view of the Waitematā Harbour. He also employed the Soalls to keep the office-residence and its grounds.[5]: 94 Though Lugard had completed the front portion of Fort Britomart's barrack building in September 1841, the rear section had by 28 February 1842 only been built to the loopholes on one side when he returned to Sydney. Like the barracks at Russell, Lugard had constructed Auckland's fort and soldiers' barracks as a matter of immediate necessity under a paucity of means with soldiers drawn from the 80th Regiment acting as military artificers. Bennett set to completing the work, amongst other matters, and resolving cost overrun caused by New Zealand's unforeseeable circumstances.

Auckland Mechanics' Institute

A meeting had been held as early as mid-July 1841 to establish the Auckland Mechanics' Institute, its objective—"the acquirement and diffusion of useful knowledge, by means of a library, museum, reading room, and discussions and lectures" confined to mechanical science and natural productions—and the rules.[27] On 5 September 1842 the Institute elected the Commanding Royal Engineer, George Bennett, as their president, along with his former senior civil assistant in Ireland and newly appointed Surveyor General, Charles Whybrow Ligar, as vice-president.[28] The Acting Governor, Willoughby Shortland, accepted nomination as patron on 22 September.[29] The Institute opened its library in rented cottage from 7:00 pm, 30 September 1842, with John Kitchen as librarian.[30] By 1843 they could provide members with a selection of works by approved authors, and their president hoped the ongoing debates "will be instructive and engender a well directed taste for reading."[31]

Tauranga Campaign of 1842

Following the death of the Governor, Captain William Hobson, RN, on 10 September 1842, Acting Governor Willoughby Shortland, RN, intervened in a Maori dispute of ancient origins with a view to end such conflicts. The Tauranga Campaign, December 1842 to January 1843, led by Major Thomas Bunbury, 80th Regiment, exposed the deficiency of military capacity in New Zealand, if not a better process for justifying such campaigns.

Bennett took opportunity to examine pā. Impressed by Maori knowledge of and practice in fortification and stratagem, his Report on the pahs of New Zealand, and the means necessary to attack them with plans and sections of some pahs to the Inspector General of Fortifications in 1843 conceived that without sufficient artillery, assaulting a strong pā would result in considerable loss to the assailants.[3]: 47–49 Tragedy through belligerence with insufficiency of means and ignorance of expert assessment was later felt in the siege of the new pā of Puketutu and Ōhaeawai in May and July 1845. Collinson commented that "the field pieces were such as Lieutenant Bennett, two years before, had pronounced useless against ordinary pahs, and this was known to be one of extraordinary strength."[3]: 59–62

Bennett had equipped the expedition for field operations, with tools and materials including some remaining from his house, and carried on the construction of barracks and other facilities at Hopukiore / Mt Drury, Maunganui, with the mechanics.[32]: 391 In consequence of Bunbury's letter to the General commending the engineer's exertions, Bennett advanced to rank of 2nd Captain in September 1843.

Thorndon Barracks

On 23 January 1844 he ventured to Wellington in the Colonial Brig Victoria, to arrange barracks for soldiers of the 65th Regiment.[33] As a prison had been blunderingly built on part of the Mount Cook military ground in 1843, rendering it unfit for military barracks, Bennett gained authorisation from Governor Robert FitzRoy, having recently arrived in New Zealand and then in Wellington, to obtain a piece of the 10 acre Native Reserve at Thorndon Flat.[34][11]: f103 In exchange, land preferred by and better suited to Maori would be set apart for their exclusive use.[35]: 55

Thorndon Barracks required the triangular area within the fork and ditches of the Whakahikuwai and Tiakiwai streams, from Molesworth Street to a frontage on Hobson Street. Confident of a land grant, Bennett completed the barrack proposal by May 1844—estimate and plans of the site, hospital, hospital kitchen and privy, soldiers' barracks, officers quarters, officers' kitchen and officers' privy, guard room and cells, barrack sergeant's quarters and store—some being copies of Fort Britomart buildings. Like Albert Barracks in 1845, he would not have considered it justifiable to propose barrack buildings on ground not made over to the Board of Ordnance, and no permanent structures were built. In 1848 Lieutenant Collinson, RE, followed up the request for the Crown grant of the land to Ordnance but the Executive Council declined a grant, though allowed temporary use. Attorney General Daniel Wakefield's view was that reserved lands couldn't be granted without the consent of the Maori beneficially interested in them.[35]: 60–61 The site is now remodelled as Katherine Mansfield Memorial Park, Queen Margaret College, and SH 1 Wellington Urban Motorway.

Great South Road

Bennett mentioned building roads through the island, ready for military use, in 1843.[11]: f98v The Southern Cross, 6 April 1844, expressed the want of proper roads to convey surplus produce to markets. Cutting roads from Auckland through the interior to Wellington and to the Bay of Islands would be immediately beneficial. If troops were needed, "they would at least be better employed in making roads than idle in barracks or drinking in town. Captain Bennett, the Officer of Engineers, would also have an opportunity of keeping himself in the practice of his profession, and connecting his name with the most useful undertaking in the Colony. Under his directions we might expect to have the best lines selected for the most important of our roads."[36] The Great South Road from Newmarket, apparent since 1843,[37] forced its way south as a military road from 1861.

Grange and gardens

Bennett had purchased land about Auckland—suburban farms at Epsom and Mt Eden near Three Kings in 1842 and 1843, as well as a site for his new residence on the heights of Khyber Pass Road, Lot 7, Section 3, just over 5 acres, at the head of Grafton Gully / Glen Ligar in July 1843. There, with its commanding view over the harbour and islands, Government House and cemetery, he established Bennett's Grange, later reported as named Glenhead.[38] The view was painted by several notable landscape artists—John Guise Mitford[39][40][41] and the Reverend John Kinder[42] in the 1840s and 1850s.

The newly formed Agricultural Society in Auckland held its first show on Tuesday, 19 December 1843: "The exhibition of Floral, Horticultural, and Farm Produce, was held in the large room of Hart's Hotel, and was in every respect highly creditable to the colony, and to this settlement in particular. Considering the very early stage of the agriculture of this settlement, the exhibition may be said to have exceeded the expectations of the most sanguine. The flowers from the garden of Lieutenant Bennet were exceedingly beautiful, and show how much the lovers of Flora may expect in such a delightful climate as this." "Mr. Bennett" was awarded the prize for the Flower Bouquet category.[43] Many flowering plants, which he was the first to have in the Colony, went by his name.[5]: 100

Flax fibre industry

The flax trade was extensive in the north of Ireland when Bennett left for New Zealand. It was thought that a national good might be achieved from it, and to that end a society was formed in Belfast in 1841 to advance good practice and economy. A fibre industry in New Zealand made good export sense and to that end efforts were put to mechanising the production of fibre from New Zealand flax, Phormium tenax.[44] By October 1843 and late 1844, Bennett's cultivation of common flax, Linum usitatissimum, at his Auckland suburban farm and experiments in processing by boiling green flax with fullers earth, producing some very fine examples, caught the interest of The Southern Cross: "We understand Mr. Bennet is about adapting machinery to the after process of cleaning. We trust his experiments will succeed. Mr. Bennet has always manifested a praiseworthy interest in furthering the prosperity of the colony since he came amongst us."[45][46]

The New-Zealand Festival

In May 1844 about two or three thousand Maori from various tribes and remote districts peacefully assembled together for a week at Epsom, about three miles from Auckland town. Though The Southern Cross reported that the meeting was "for the purpose of still more cementing that friendship and good feeling which their now superior knowledge teaches to be essential to their comfort and happiness", Bennett noted that it was "for the purposes of a correro with the Governor—The natives wish to sell their land to whom they please, & the native chiefs wish to be governor over their own people with their own laws—how far this is applicable with English rule I leave for wiser heads."

Joseph Jenner Merrett's panorama of the event on Saturday 11 May 1844, The New-Zealand Festival, looking across the Market Road / Great South Road intersection to Mount Saint John, depicts the arrival of Governor Robert FitzRoy in naval uniform, followed by a military officer, Attorney General William Swainson, Colonial Treasurer Alexander Shepherd and others on horseback, with Maori chiefs and Europeans in procession along "Market Road" from Remuera. Colonel William Hulme and officers of the 96th Foot went on foot.[1][11][47] "Each tribe occupied a separate portion of the ground, where temporary huts had been erected for their accommodation; and His Excellency visited each of them, shaking hands with the principal chiefs, and addressing them in short speeches, which were interpreted by the Chief Protector of Aborigines. After these proceedings were over, the natives performed a war dance in honor of His Excellency."[48] Having seen Maori war dances once or twice, Bennett found it entertaining rather than frightful.[11]

In the area of today's Mount Saint John Avenue, Apihai Te Kawau's Auckland tribes had arranged, as presents for distribution to their visitors, a 500 yard long tent of blankets, in front of which was a wall of potatoes in kete (basket) and salted sharks for flavour. Bennett commented: "These were all meant for presents to the Visitors & were distributed much to their satisfaction—The day after the distribution took place Auckland was visited by a succession of Maoris each with his share of potatoes on sale" [11]

Bay of Islands trouble

Following Hōne Heke's flagstaff felling in July 1844, Governor FitzRoy, Lieutenant Colonel William Hulme, 96th Regiment, Bennett and 15 soldiers, sailed for the Bay of Islands in the brig Victoria and HMS Hazard on 22 August, to amicably settle grievances. Bishop Selwyn and George Clarke, Protector of Aborigines, also travelled to the Bay of Islands.[49] They found 160 troops from New South Wales, camped at the Bay. The total force including Hazard's sailors and marines amounted to some 250 men, confident of being able to give Heke and followers a severe chastisement, even at his pā. FitzRoy, Hulme and Bennett thought differently.[50]: 31

FitzRoy asked Bennett to report on the roads to Kerikeri and Waimate. They were good in places but impractical for moving heavy artillery in others. Bennett also tried to draw local farmers' drays and bullocks into military service, but not without encountering their fear of revenge if they were to ever seen to be voluntarily involved. If the Government required them, the soldiers would take them, resolved the matter.[11]: f107 [51] Bennett had also observed that the country was "utterly impracticable for the evolutions of disciplined troops".[50]: 33

Government House at Russell (Okiato) had been destroyed by fire in 1842 and Lugard's temporary barracks, just a few years old, had fallen into disrepair. On 30 August, Hulme and Bennett agreed that it was "useless to repair or let it remain" and had all windows, iron fastenings, doors, hinges and locks removed. Fitzroy, Hulme, Bennett, Lieutenant Barclay and Mr Hamilton arrived back in Auckland on the Government Brig Victoria on 6 September, with HMS Hazard and the troops.[52] FitzRoy's consultations with Maori and consequent solutions seemed to have helped. The Southern Cross wrote: "We do not apprehend anything serious from these war-like preparations. Our friends in the other colonies need have no fear for our safety."[49]

Trouble had also been brewing at Port Nicholson and in late January the Robert FitzRoy intended sending Bennett there to examine the Hutt, in preparation for an expedition to occupy and build a fort. To FitzRoy's order, he designed a transportable wooden blockhouse to shelter 20 soldiers, of which five would be made for Auckland, Russell, Whangārei and the Hutt Valley. The blockhouses measured internally 17 ft x 20 ft x 9 ft stud, with common gable weatherboard roof, loopholed walls of 6 in × 6 in (150 mm × 150 mm) kauri posts vertically arranged between top and bottom plates; room enough for 16 beds. It was envisaged they could be erected in less than twenty-four hours in any location conveyed to by water and serve as temporary barracks for some of the troops expected from Sydney.[53]

Defence of Kororāreka

Heke had resumed agitation by felling Kororāreka's flagstaff again on 10 January 1845. On 23 January, in consultation with Hulme and Bennett, the Executive Council ordered a blockhouse be placed to protect the flagstaff reinstated in its original position on Flagstaff Hill.[54]: 113–114 Perhaps aware of his possible casualty, Bennett signed his will on 25 January.

In the latter half of February, one of Bennett's transportable blockhouses was shipped to Kororāreka, with Graham, on HMS Hazard. Its components were brought ashore between 4:00–10:00 am on 17 February and carried up Flagstaff Hill by Hazard's crew, where it was erected by them over the next two days of squalls and fine weather. The flagstaff was taken up on 22 February, erected, ironclad, rigged on 28 February and 1 March, and painted on 5 March.[55] Complete, the blockhouse flanked an ironclad flagstaff enclosed within a strong triangular palisade, all surrounded by a "V" ditch 16 ft wide x 12 ft deep and inaccessible scarp; all devised by Bennett to "puzzle John Heki to cut it down a fourth time."[11]: f117v A second blockhouse, Fort Phillpotts, with a breastwork and two guns on a platform, was built by civilians lower down the hill. The navy installed a gun battery over Matavia Pass.[56] Then, in the early morning of 11 March 1845, the Battle of Kororāreka began. Bennett noted in his journal:

without any concerted plan of operations Poor young Campbell having unfortunately left the Blockhouse (leaving only 3 men within) to dig some foolish trench some half mile off—allowed his post to be surprised—The 4 men were killed—on looking back & seeing the Bl. Ho. surrounded & in possession of a mass of natives he retired down the hill to a second Bl. Ho. made by the Civilians—& thus the flagstaff & key of the Position fell into John Heki's hands.[5]: 97–98

Defence of Auckland

Bennett had been working through improvements to Fort Britomart through 1844–1845—designs and estimates for cells, magazine, sentry boxes, guardhouse, commissariat store. News of Kororāreka having been attacked on 11 March arrived in Auckland by the Government Brig Victoria on 14 March, landing women and children from the Bay of Islands. The Legislative Council, meeting on Saturday, 15 March 1845, put their agenda aside to read the despatches from Kororāreka, and after discussion, passed the resolution:

That the Barracks be immediately made impregnable against musketry attack, and sufficient as a place of refuge for the habitants of Auckland—and that the Male population of the Settlement be sworn in as special Constables and efficiently armed, and that such arrangements and precautions be made that such an armed force can be brought into active service at the shortest notice under experienced and efficient leaders.[57][58][59]

Rumour spread that Heke would attack Auckland, perhaps within a day or two; his forces generously estimated to be about two thousand men.[50]: 46 Bennett commenced preparing Fort Britomart to the Governor's instruction and the approved plan from 17 March, employing all available military and civilian labour. The fort was strengthened with ditch and parapet dimensions based on those used at the Lines of Torres Vedras of the Peninsular War. The remaining four blockhouses were reassigned—two to flank Fort Britomart's parapet, one inside its gate and one, surrounded by a ditch, to the hill about 300 yards behind Government House. George Graham fortified St Paul's Church as a refuge for the people. FitzRoy's coordination of the defence plan tended to ruffle, particularly Hulme and Bennett. In any case, what happened at Kororāreka was not to be repeated at Auckland.

Bennett also advised FitzRoy on a substantial barrack needed to quarter the expected troops. Albert Barracks, as it came to be called, was proposed to be built on the high ground specially reserved for public purposes behind Government House, though for military use, title was required to be granted to the Board of Ordnance. Bennett's proposal of enclosing the barracks, assuming that FitzRoy would agree that temporary field works were inadequate for keeping soldiers in, was for a loopholed defensible wall. The bastioned loopholed scoria stone wall was built several years later, in 1848. In due course Bennett received orders to prepare plans and estimates for a temporary barrack, officers quarters, mess house and kitchens, cook houses, guard house and cells for five-hundred men. Graham carried through with plans and estimates, and with Bennett's consent, discussion with FitzRoy, from which a temporary wooden barrack for 86 men would be built first.[60]

By late March Bennett was reporting very ill, fearing "getting worse every week". He had endured months of increasingly severe headaches but persevered. He turned out with the rest ready for action during a scare at 3:00 am, 1 April, but after half an hour, with nothing likely to happen and barely able to stand, he had to retire.[5]: 98–99 Whilst FitzRoy dealt to military plans with Hulme, The Southern Cross, 12 April, reported:

Much as has been done towards placing the barracks in a tenable state of defence, to the great credit of the Engineer department, we think that more is indispensable, anticipating an actual insurrection and attack from the Natives. The western side of the town is quite unprotected, and Queen-street and its neighbourhood might be ransacked and burnt with impunity.[61]

The Auckland Battalion of Militia moved to construct Fort Ligar, an earth redoubt with surrounding ditch and a Martello gun tower at its centre, on the western ridge in mid April. Surveyor General Charles Ligar had been appointed as their Lieutenant Colonel. Defended by two militia companies, it intended to provide further refuge and stores.[62][63]: 121 [64]: 24

Death

Captain George Augustus Bennett died about 11:00 am, Wednesday, 30 April 1845. Some thought had been given to a return to England, though he was deteriorating to general debility with some four hours of activity each day.[5]: 99 Arrangements were being made in New South Wales for Captain William Biddlecomb Marlow, RE, to relieve him for a return to Sydney for the benefit of his health.[65] Mrs Soall was unremitting in his care. The Reverend John Churton who'd visited that morning, imagined the cause to be a rapid swelling of the throat. Commander David Robertson-Macdonald, RN, HMS Hazard, severely wounded at Kororāreka, was also recovering there.[5]: 99, 102 [11]: 99

The Governor and suite, and almost all Aucklanders, attended the funeral at St Paul's Church on 2 May. It was performed with full military honours and the flag was lowered. He was buried adjacent to Governor Hobson's grave at St Paul's burial grounds in Symonds Street cemetery. The Auckland Times wrote:

The death of this Officer was not in the slightest degree suspected, as a likely event, by any, but his medical attendants. Capt. BENNETT was only 38 years of age; but in the Colony, few, if any were more respected. Not being a married man, he nevertheless invested a considerable capital in the country, and gave encouragement, to others to follow his example. Captain Bennett ever set an example of being a Colonist among us, as well as an Officer of the Government service, and doubtless, he will be much missed, by the Auckland people, even if it were only on that account. But his spontaneous kindness as "President of the Mechanic's Institute," and his other encouragement by every useful purpose, or contrivance for the advancement of the Colony, of course, made his sudden disappearance, a loss to the place,—a loss which they cannot but deplore, especially at the present critical moment,—when it is so necessary, and yet so difficult, to provide for the renewal of actual Colonists.[2]

Bennett's grave vanished during the 1960s Auckland Southern Motorway works, and construction of the Anglican memorial wall and platform surrounding Captain Hobson's grave.[5]: 105–106

Legacy

Contour line

Contour lines "united with light and shade for perfection and clarity" persist in new map technologies[66]

Auckland Libraries

The Auckland Mechanics' Institute carried on with technical classes, lectures and a fine arts and industrial exhibition in 1873[67] but foundered in the depression that decade. The institute, with its library established under Bennett's presidency, passed to the Auckland City Council to form the Auckland Free Public Library in 1879.[68] The merging of Auckland's territorial local authorities into one Auckland Council on 1 November 2010, reformed the public-library network into the largest in Australasia—Auckland Libraries.[69]

St David's Presbyterian Church

Elizabeth, daughter of James and Elizabeth Soall, inherited Bennett's property, Glenhead, in Khyber Pass Road. In 1901, she sold a section of it to the Presbyterian Church for the relocation of St David's Presbyterian Church in early 1902. In 1924, the Presbyterian Church purchased Glenhead to build larger church for the growing congregation and as a war memorial to members who had died in the Great War. Bennett's house was replaced with the old wooden church. The foundation stone for the new brick church was laid on Anzac Day 1927 and the opening dedication service held on 13 October.[70]

The New Zealand Engineers were permitted to install within the church on 3 June 1928, a memorial tablet to 3 Field Company members lost in the war. The Engineers chose St David's for it being a soldiers' memorial church, its location and in respect to the Reverend William Gray Dixon, Minister of St David's, 1899–1910, who'd had been their chaplain, 1906–1910. The Corps of Royal New Zealand Engineers have held an annual memorial service there since.[70] Their choice of place, in it also being on the former estate of the Commanding Royal Engineer of New Zealand, was seemingly serendipitous.[5]: 106

Military Works

Though Hōne Heke had burnt Bennett's flagstaff blockhouse after the battle in 1845, its platform and defensive ditch survive in good order. The present flagstaff dates from 1858.[64]: 18

Crest of Bennett

Crest—Out of a mural crown or, a lion's head gules. Motto—De bon vouloir servir le roy (To serve the king with good will).[71]

Publications

- Bennett, George Augustus (1860). "Pah". Aide-mémoire to the Military Sciences. 2 (2 ed.). London: John Weale; Lockwood & Co.: 587–588.

References

- ^ a b The New-Zealand Festival, Hobart: Samuel Augustus Tegg, 1845 – via Alexander Turnbull Library

- ^ a b c "Died on Wednesday last, Captain G. A. Bennett, R.E. &c, &c". Auckland Times. Vol. 3, no. 121. 6 May 1845. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Collinson, Thomas Bernard (1853). "2. Remarks on the Military Operations in New Zealand" (PDF). Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corp of Royal Engineers. New Series 3. London: John Weale: 47–50.

- ^ a b c d Connolly, Thomas William John (1898). Richard Fielding Edwards (ed.). Roll of Officers of the Corps of Royal Engineers from 1660 to 1898. Chatham: The Royal Engineers Institute.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Heath, Philip; Grimmett, Ross (November 2005). "A Tale of Two Letters: The Death of Captain George Augustus Bennett, Royal Engineers". The Volunteers: The Journal of the New Zealand Military Historical Society. 31 (2).

- ^ a b William J C Moens, ed. (1893). The Publications of the Harleian Society: Hampshire Allegations for Marriage Licences Granted by the Bishop of Winchester. 1689 to 1837. Vol. 1. London: The Harleian Society. p. 63.

- ^ Connolly, Thomas William John (1857). History of the Royal Sappers and Miners, from the Formation of the Corp in March 1772, to the Date When its Designation was Changed to that of Royal Engineers in October 1856. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts.

- ^ a b c d e Bennett, Frederick (1909). The Story of W. J. E. Bennett: Founder of S. Barnabas', Pimlico and Vicar of Froome-Selwood and of His Part in the Oxford Church Movement of the Nineteenth Century. London: Longmans, Green, & Co.

- ^ "Col Thomas Alston Brandreth (24890)". Edward Liveing Fenn. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ "William Bennett (d.1790)". Three Decks—Warships in the Age of Sail. Cy Harrison. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bennett, George Augustus (1832–1845), Journal, unpublished – via National Library of New Zealand

- ^ "Friday Night's Gazette". Hampshire Chronicle. 23 July 1827. p. 4.

- ^ Research Essay on the Journal of George Augustus Bennett, Wellington: unpublished, c. 1967 – via National Library of New Zealand

- ^ The House of Commons (1828). Reports from Committees: (2.) Public Income and Expenditure. Vol. 5. The House of Commons. pp. 94–95.

- ^ "Proceedings and Papers". The Journal of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society. 4 (1): 23–35. 1862. JSTOR 25502619. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ McWilliams, Patrick (2002). Ordnance Survey Memoirs of Ireland: Index of People and Places. Belfast: The Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University Belfast.

- ^ Stubbs, FW (1908). "Place Names in the County of Louth". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society: 39.

- ^ "Report from the Select Committee on Ordnance Survey (Ireland); Together with Minutes of Evidence, Appendix and Index". Parliamentary Papers, Session 1846. 15. Great Britain: House of Commons: 33. 1846.

- ^ a b Portlock, Joseph Ellison (1869). Memoir of the Life of Major-General Colby. London: Seeley, Jackson & Halliday. pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b "Report from the Select Committee on Ordnance Survey (Ireland); Together with Minutes of Evidence, Appendix and Index". Parliamentary Papers, Session 1846. 15. London: The House of Commons. 1846.

- ^ a b c "Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Inquire into the Facts Relating to the Ordnance Memoir of Ireland; Together with Minutes of Evidence, Appendix and Index". Parliamentary Papers, Session 1844. 30. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. 1844.

- ^ a b Andrews, John Harwood (1975). A Paper Landscape: The Ordnance Survey in the Nineteenth Century. Clarendon Press.

- ^ "New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator". Vol. 2, no. 125. 19 March 1842. p. 2 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Shipping Intelligence". The Australian. 28 December 1841. p. 2. Retrieved 17 May 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ "Departures". The Sydney Herald. 31 January 1842. p. 2. Retrieved 20 May 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ "New Zealand Herald and Auckland Gazette". Vol. 1, no. 55. 26 February 1842. p. 2.

- ^ "Domestic Intelligence. Mechanics' Institute". New Zealand Herald and Auckland Gazette. Vol. 1, no. 2. 17 July 1841. p. 3.

- ^ Auckland Mechanics' Institute (1832–1880), Minute Books – via Auckland Libraries, Special Collections

- ^ "Auckland Times". Vol. 1, no. 7. 26 September 1842. p. 2.

- ^ "Auckland Mechanics' Institute. Opening of the Library". Auckland Times. Vol. 1, no. 7. 26 September 1842. p. 1.

- ^ Northey, Glenda (1998). Accessible to All? Libraries in the Auckland Provincial Area, 1842–1919 (MA). Auckland: University of Auckland, Department of History.

- ^ Best, Abel Dottin William (1966). Nancy M. Taylor (ed.). The Journal of Ensign Best, 1837–1843. Wellington: R. E. Owen.

- ^ "Shipping List". Auckland Times. Vol. 2, no. 55. 30 January 1844. p. 2.

- ^ "Barracks". New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator. Vol. 4, no. 323. 10 February 1844. p. 2.

- ^ a b Quinn, S P (29 January 1995), Draft Report on: The Wellington Tenths Reserve Lands (PDF)

- ^ "Domestic Intelligence: Roads and Bridges". The Southern Cross. Vol. 51. 6 April 1844. p. 2.

- ^ "A Farm to Let". The Southern Cross. Vol. 4, no. 197. 31 March 1849. p. 1.

- ^ "Married". New Zealander. Vol. 17, no. 1620. 26 October 1861. p. 3.

- ^ Mitford, John Guise (1843), Grafton Gully, 1942/6 – via Auckland Art Gallery

- ^ Mitford, John Guise (1843), "View from above Grafton Gully showing Graveyard and Government House, Auckland", The Hobson Album, E-216-f-111 – via National Library of New Zealand

- ^ Mitford, John Guise (1843), "Entrance to the Harbour, Auckland", The Hobson Album, E-216-f-041 – via National Library of New Zealand

- ^ Kinder, John (1856), Glen Ligar from Mr Connell's garden at the head of the glen, 12,099

- ^ "Domestic Intelligence: Agricultural Society". The Southern Cross. Vol. 1, no. 36. 23 December 1843. p. 3.

- ^ "New Zealand Flax Made at Last Available as an Export". The Southern Cross. Vol. 1, no. 25. 7 October 1843. p. 2.

- ^ "Domestic Intelligence: Flax Dressing". The Southern Cross. Vol. 1, no. 28. 28 October 1843. p. 3.

- ^ "Original Correspondence". The Southern Cross. Vol. 2, no. 83. 16 November 1844. p. 3.

- ^ "Domestic Intelligence: Native Feast". Auckland Chronicle and New Zealand Colonist. Vol. 2, no. 41. 16 May 1844. p. 2.

- ^ "Native Feast". The Southern Cross. Vol. 2, no. 57. 18 May 1844. p. 2.

- ^ a b "John Heki". The Southern Cross. Vol. 2, no. 71. 24 August 1844.

- ^ a b c FitzRoy, Robert (1846). Remarks on New Zealand in February 1846. London: W. and H. White.

- ^ Williams, William; Williams, Jane (1974). Frances Porter (ed.). The Turanga Journals, 1840–1850: Letters and Journals of William and Jane Williams, Missionaries to Poverty Bay. Victoria University Press. pp. 270–313.

- ^ "Shipping List". The Southern Cross. Vol. 2, no. 73. 7 September 1844.

- ^ Graham, George (24 January 1845), WO 44/175: No. 13. Details of an Estimate for Portable Defensible Blockhouses conformably with the order of Lieut. Colonel Hulme 96th Regt Commanding Troops in New Zealand, pp. 269–270 – via The National Archives

- ^ Wards, Ian (1968). The Shadow of the Land: A study of British policy and racial conflict in New Zealand 1832–1852. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs.

- ^ Captains' Logs, HMS Hazard, 1 April 1841–6 May 1847. 1841–1847.

- ^ "Narrative of Events at the Bay of Islands". The New-Zealander. Vol. 1, no. 1. 7 June 1845. p. 2.

- ^ Legislative Council of New Zealand, Session 5, 1845, Auckland, 1845

- ^ "Legislative Council: Saturday, March 15, 1845". The Southern Cross. Vol. 2, no. 101. 22 March 1845. p. 3.

- ^ Buick, Thomas Lindsay (1926). New Zealand's First War, or the Rebellion of Hone Heke. Wellington: W.A.G. Skinner, Government Printer. pp. 85–88.

- ^ Graham, George (12 June 1845), WO 44/175: No. 16. Graham to the Inspector General of Fortifications, pp. 262–263 – via The National Archives

- ^ "Defence of the Town". The Southern Cross. Vol. 2, no. 104. 12 April 1845. p. 3.

- ^ "The Southern Cross". Vol. 3, no. 105. 19 April 1845. p. 3.

- ^ Smith, Ian (1989). "Fort Ligar: A Colonial Redoubt in Central Auckland". New Zealand Journal of Archaeology. 11: 117–141.

- ^ a b Prickett, Nigel (2016). Fortifications of the New Zealand Wars (PDF). Wellington: Department of Conservation.

- ^ "Military Intelligence". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 May 1845. p. 2. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ "Londonderry/Derry". topographic-map.com. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ "Mechanics' Institute. The Fine Arts and Industrial Exhibition". The Daily Southern Cross. Vol. 29, no. 5101. 29 December 1873. p. 3.

- ^ Auckland Free Public Library Aid Act 1879. General Assembly of New Zealand in Parliament. 19 December 1879. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "History of Auckland Libraries". Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ a b Ryburn, W M (1964). The Story of St. David's Presbyterian Church, Auckland, 1864–1964. Len Bolton & Company.

- ^ Almack, Edward (1904). Bookplates. London: Methuen & Co. p. 66.

External links

- "Captain George Augustus Bennett". Find a Grave.