George Ade

George Ade | |

|---|---|

Ade in 1904 | |

| Born | February 9, 1866 Kentland, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | May 16, 1944 (aged 78) Brook, Indiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Fairlawn Cemetery, Kentland, Indiana |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, newspaper columnist, and playwright |

| Parents |

|

George Ade (February 9, 1866 – May 16, 1944) was an American writer, syndicated newspaper columnist, librettist, and playwright who gained national notoriety at the turn of the 20th century with his "Stories of the Streets and of the Town", a column that used street language and slang to describe daily life in Chicago, and a column of his fables in slang, which were humorous stories that featured vernacular speech and the liberal use of capitalization in his characters' dialog.

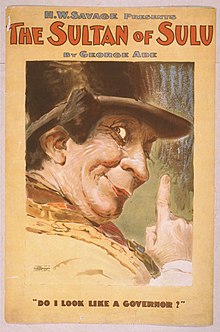

Ade's fables in slang gained him wealth and fame as an American humorist, as well as earning him the nickname of the "Aesop of Indiana". His notable early books include Artie (1896); Pink Marsh (1897); Fables in Slang (1900), the first in a series of books; and In Babel (1903), a collection of his short stories. His first stage work produced for the Broadway stage was the operetta The Sultan of Sulu, for which he wrote the libretto in 1901. The Sho-Gun and his best-known plays, The County Chairman and The College Widow, were simultaneously appearing on Broadway in 1904. Ade also wrote scripts and had some of his fables and plays adapted into motion pictures.

During the first quarter of the 20th century, Ade, along with Booth Tarkington, Meredith Nicholson, and James Whitcomb Riley helped to create a Golden Age of literature in Indiana.

The Purdue University graduate from rural Newton County, Indiana, began his career in journalism as a newspaper reporter in Lafayette, Indiana, before moving to Chicago, Illinois, to work for the Chicago Daily News. In addition to writing, Ade enjoyed traveling, golf, and entertaining at Hazelden, his estate home near Brook, Indiana. Ade was also a member of Purdue University's board of trustees from 1909 to 1916, a longtime member of the Purdue Alumni Association, a supporter of Sigma Chi (his college fraternity), and a former president of the Mark Twain Association of America. In addition, he donated funds for construction of Purdue's Memorial Gymnasium, its Memorial Union Building, and with David Edward Ross, contributed land and funding for construction of Purdue's Ross–Ade Stadium, named in their honor in 1924.

Early life and education

George Ade was born in Kentland, Indiana, on February 9, 1866, to farmer and bank cashier John and Adaline Wardell (Bush) Ade.[1] George was the second youngest of the family's seven children (four boys and three girls). George's father served as the Newton County, Indiana, recorder, and was also a banker in Kentland; his mother was a homemaker. George enjoyed reading from an early age, but he disliked manual labor and was not interested in becoming a farmer. Although he graduated from Kentland High School in 1881, his mother did not think he was ready for college. As a result, Ade remained in high school for another year before enrolling at Purdue University in 1883 on scholarship.[2][3][4]

Ade studied science at Purdue, but his grades began to falter after his first year when he became more active in the college's social life. Ade also developed an interest in the theater and became a regular at the Grand Opera House in Lafayette, Indiana. In addition, he joined the Sigma Chi fraternity. Ade also met and began a lifelong friendship with cartoonist and Sigma Chi fraternity brother John T. McCutcheon. Ade graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree from Purdue in 1887. He briefly thought about becoming a lawyer, but abandoned the idea to pursue a career in journalism.[2][5][6][7]

Career

Newspaper reporter

Ade did not begin his writing career in college. In 1887, after graduating from Purdue University, he worked in Lafayette, Indiana, as a reporter and telegraph editor for the Lafayette Morning News and then the Lafayette Call.[1] After the newspaper discontinued publication, Ade earned a meager paycheck writing testimonials for a patent-medicine company. By 1890 he had moved to Chicago, Illinois, and resumed his career as a newspaper reporter, joining John T. McCutcheon, his college friend and Sigma Chi fraternity brother, at the Chicago Daily News (which later became the Chicago Morning News and the Chicago Record), where McCutcheon worked as an illustrator.[2][7]

Ade's first assignment was writing a daily weather story for the Morning News. He also covered some major news events, including the explosion of the steamer Tioga on the Chicago River; the heavyweight championship boxing match between John L. Sullivan and James J. Corbett in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1892; and the World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago World's Fair) in 1893.[6]

Syndicated columnist

While working for the Chicago Record, Ade developed his talent for turning local human-interest stories into humorous satire, which became his trademark.[8] Beginning in 1893, Ade was put in charge of the daily column, "Stories of the Streets and of the Town," which frequently included McCutcheon's illustrations. Through Ade's use of street language and slang, the column described daily life in Chicago and introduced some of his early literary characters, which included Artie, an office boy; Doc Horne, a "gentlemanly liar"; and Pink Marsh, an African American shoeshine boy who worked in a barbershop.[6][9] Collections of Ade's columns were subsequently published as books, such as Artie (1896), Pink Marsh (1897), and Doc' Horne (1899), which also helped to increase the popularity of his column. Ade's newspaper columns also included dialog and short plays containing his humorous observations of everyday life.[8]

Ade first introduced his fables in slang in the Chicago Record in 1897. "The Fable of Sister Mae, Who Did As Well As Could Be Expected" appeared on September 17, 1897; the second one, "A Fable in Slang," appeared a year later; others followed in a weekly column. These humorous stories, complete with morals, featured vernacular speech and Ade's idiosyncratic capitalization of the characters' dialog. Ade left the Chicago Record in 1899 to work on nationallysyndicated newspaper column of his fables in slang. Fables in Slang (1900), the first in a series of book of Ade's fables, was popular with the public and for nearly twenty years more collections of his fables were compiled into additional books, ending with Hand-Made Fables (1920). Ade's fables also appeared in periodicals, the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company produced them as motion-picture shorts, and Art Helfant also turned them into comic strips.[6][8][10]

Playwright, librettist, and author

After Ade's newspaper columns went into syndication in 1900, he began writing plays. His first stage work produced for Broadway was the musical The Night of the Fourth[11] which premiered on January 21, 1901 at the Victoria Theatre. Ade wrote the book to this musical with Max Hoffmann as composer and J. Sherrie Mathews as lyricist. It was a critical flop and closed after fourteen performances.[12]

Ade's next show on Broadway was The Sultan of Sulu; an operetta with music by Alfred G. Wathall for which Ade was the librettist.[13] The opera's plot was about the American military's efforts to assimilate natives of the Philippines into American culture.[14] It premiered at Wallack's Theatre on December 29, 1902 in a production produced by opera impresario Henry W. Savage.[15] A popular success, it ran for 200 performances at that theatre; closing on Jun 13, 1903. It then embarked on a national tour which included a return engagement to Broadway in November 1903, this time at the Grand Opera House. The composer Nathaniel D. Mann contributed one song to the operetta, "My Sulu Lulu Loo".[16]

His other works for Broadway include Peggy from Paris (1903), a musical comedy; The County Chairman (1903), a piece about small-town politics; The Sho-Gun (1904), a musical set in Korea; and The College Widow (1904), a comedy about college life and American collegiate football.[4][17][18]

Not all of Ade's theatrical productions were successes, such as The Bad Samaritan (1905), but three of his plays (The College Widow, The Sho-Gun, and The County Chairman) were simultaneously appearing on Broadway in 1904. The best known and among the most successful of Ade's Broadway plays are The County Chairman and The College Widow, which were also adapted into motion pictures. Ade's final Broadway play before he retired from playwriting was The Old Town, produced in 1910.[4][17][18]

After Ade retired from writing Broadway plays in 1910, he continued to write one-act plays that small theater companies presented in theatres across the United States.[19] Marse Covington is considered to be among the best of his one-act plays. Ade also wrote scripts for moving pictures, such as Our Leading Citizen (1922 silent film), Back Home and Broke (1922 silent film), and Woman-Proof (1923 silent film) for actor Thomas Meighan. Ade also wrote two films for Will Rogers, U.S. Minister Bedlow (adapted from his 1911 play of the same name) and The County Chairman, a 1935-screen version of the play, but Ade did not get along with Hollywood filmmakers.[4][20]

By the mid-1920s, Ade's plays were no longer in fashion, but he continued to write essays, short stories, and articles for newspapers and magazines in addition to film scripts.[21] Ade also wrote about his extensive travels, but he is best known for his humorous columns, essays, books, and plays. His fables in slang stories and series of books, in addition to making him wealthy, gained him notoriety as an American writer.[5][8] His final book, The Old-Time Saloon, was published in 1931.[4]

Writing style

Ade's literary reputation rests upon his achievements as a humorist of American character. When the United States began a population shift as the first large wave of migration from rural communities to urban cities and the county transitioned from an agrarian to an industrial economy, Ade used his wit and keen observational skills to record in his writings the efforts of ordinary people to get along and to cope with these changes. Because Ade grew up in a Midwestern farming community and also knew about urban living in cities like Chicago, he could develop stories and dialog that realistically captured daily life in either of these settings. His fictional men and women typically represented the common, undistinguished, average Americans, who were often "suspicious of poets, saints, reformers, eccentricity, snobbishness, and affectation," as well as newcomers.[22]

While his humor depicts Midwestern speech and manners, it also reflects mannerisms found in late 19th-century America as well. Like Ade himself, his characters also found humor in everyday experiences, mocked pretentious social situations, and tried not take life too seriously.[22] Using a writing style similar to Mark Twain's, Ade was adept in the use of the American language. Ade's fables in slang," for example, were written in the American colloquial vernacular. He also offered genial satire and provided "a social record of how ridiculous some people make themselves."[22]

Striking features of Ade's essays and fables in slang are his creative figures of speech and liberal use of capitalization.[22][23] An example of Ade's non-standard punctuation and writing style appears in this description of a modern single woman and what Ade believes to be her high standards for an ideal husband:

Once upon a Time there was a slim Girl with a Forehead which was Shiny and Protuberant, like a Bartlett Pear.... In all the Country around there was not a Man who came up to her Plans and Specifications for a Husband. Neither was there any Man who had any time for Her. So she led a lonely Life, dreaming of the One—the Ideal. He was a big and pensive Literary Man, wearing a Prince Albert coat, a neat Derby Hat and godlike Whiskers. When He came he would enfold Her in his Arms and whisper Emerson's Essays to her. [non-standard capitalization in original][24]

In 1915, Sir Walter Raleigh, Oxford professor and man of letters, while on a lecture tour in America, called George Ade "the greatest living American writer."[25] H. L. Mencken considered selections that appeared in Ade's book, In Babel, as "some of the best short stories in America."[26]

Personal life

Hazelden farm

By the early 1900s, after twelve years in Chicago, Ade's writing had brought him financial success and he retired to a leisurely life in the country. Ade invested his earnings in Newton County, Indiana, farmland, eventually owning about 2,400 acres (970 hectares).[18][27] In 1902, George's brother, William Ade, purchased on his behalf a 417-acre (169-hectare) site of wooded land along the Iroquois River near the town of Brook in Newton County, Indiana. George initially intended to build a summer cottage. Instead, Chicago architect Billie Mann, a Sigma Chi fraternity brother, designed for Ade a two-story, fourteen-room country manor, which was constructed at an estimated cost of US$25,000. Ade named the property Hazelden, after his English grandparents' home, and moved from Chicago into the newly built residence in 1904. In addition to the Tudor Revival-style home, the property eventually included landscaped grounds, a swimming pool, greenhouse, barn, and caretaker's cottage, among other outbuildings. Ade also added an adjacent golf course and country club in 1910.[18][27][28]

Ade frequently entertained at his Indiana estate. In addition to serving as a summer home (and his permanent residence beginning in 1905), Hazelden was used for political gatherings and community events. Hazelden was the site where Republican William Howard Taft announced his candidacy for president of the United States and launched his campaign in 1908. It was also used as the site for a political rally for Theodore Roosevelt's Bull Moose Party in 1912 and a venue for an address from vice presidential candidate Charles W. Dawes in 1924. (Ade, a political conservative, supported Republican Party candidates.) Ade also hosted a homecoming party for soldiers and sailors on July 4, 1919, as well as parties and gatherings for the community, local children, Purdue University alumni, Sigma Chi fraternity brothers, members of the Indiana Society of Chicago, and golf tournaments.[8][27][29]

Other interests

Ade spent the summer months at his Hazelden estate in Newton County, Indiana, and vacationed during the winter months at a rented home in Miami, Florida. He was also an avid traveler who made trips around the world, as well as multiple trips to Europe, the West Indies, China, and Japan. In addition to his frequent travels, Ade enjoyed horse racing and golf.[19][8]

Ade, who never married, corresponded regularly with a wide circle of friends and was active in literary, civic, and political organizations. In 1905 he was a cofounder with Edward M. Holloway and John T. McCutcheon of the Indiana Society of Chicago, a literary organization. Ade also served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Chicago in 1908.[19][8]

Ade was a longtime supporter of Purdue University and Sigma Chi,his college fraternity. He served as national president of Sigma Chi in his later years[7][8] and as a member of Purdue's board of trustees from 1909 to 1916. Ade was also a member of the Purdue Alumni Association.[4] Ade donated funds for construction of Purdue's Memorial Gymnasium and its Memorial Union Building. In 1922, Ade and David Edward Ross, another Purdue alumni, bought 65 acres (26 hectares) of land for use as the site of a new football stadium at Purdue's campus in West Lafayette, Indiana. In addition, Ade and Ross provided financial support construction of the facility, which was formally dedicated on November 22, 1924, and named Ross–Ade Stadium in their honor.[19][29] Ade also led a fund-raising campaign to endow the Sigma Chi mother house at Miami University, where the fraternity was originally established. Ade also authored the Sigma Chi Creed in 1929, which is one of the central documents of the fraternity's philosophies.[citation needed]

In his later years Ade was a member of National Institute of Arts and Letters (American Academy of Arts and Letters) and an executive committee member of the Authors Guild. Purdue University awarded Ade an honorary degree in the humanities in 1926 and Indiana University awarded him an honorary law degree in 1927. During the early 1940s, he also served as president of the Mark Twain Association of America. Ade's activities slowed after he suffered a stroke in June 1943 that left him partially paralyzed and a series of heart attacks in 1944.[4][30]

Death and legacy

Ade fell into a coma after suffering a heart attack and died on May 16, 1944 in Brook, Indiana at the age of 78. His remains are interred at Fairlawn Cemetery in Kentland, in Iroquois Township, Newton County, Indiana.[30]

Ade is considered a humorist, satirist, and a moralist with keen observational skills, as well as and "one of the greatest writers of his time."[22] Ade's writings reached the height of their popularity in the 1910s and 1920s. Along with the works of other Hoosier writers, such as James Whitcomb Riley, Booth Tarkington, and Meredith Nicholson, among others, Ade's writing was part of the Golden Age of Indiana Literature of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. His fables in slang gained him wealth and fame as an American humorist, in addition to earning him the nickname of the "Aesop of Indiana."[18] In more recent decades, his works have been largely forgotten.[6]

The better known of his plays that were produced on Broadway are The County Chairman and The College Widow, which were also adapted into motion pictures.[4] While the presentations of his plays and musical comedies increased his wealth and international renown, Ade's legacy includes numerous newspaper columns, magazine articles, essays, and books that describe his perspective on American life in the late nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth century.[5]

Ade bequeathed his library, manuscripts, and papers as well as most of his art objects to Purdue University.[31] Following Ade's death, ownership of Hazelden, his former home in Newton County, Indiana, was transferred to Purdue University, who relinquished the property to the State of Indiana when it could no longer afford its upkeep. The State of Indiana, unable to maintain the home, turned it over to Newton County, Indiana, officials. Ade's remaining land was distributed among his relatives. In 1962 the George Ade Memorial Association raised funds to acquire, renovate, and restore the home.[27][31] Hazelden (the George Ade House) was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.[32] The Association disbanded in 2018, and, as of 2019, Newton county officials are assessing the home's condition and plans for restoring it for use as a public historic site and events venue.[18]

Honors and awards

- Honorary degree in the humanities from Purdue University, 1926[4]

- Honorary law degree from Indiana University, 1927[4]

- Ross–Ade Stadium at Purdue University was named in honor of Ade and David E. Ross, both of whom were Purdue alumni and major donors.[19]

- The World War II Liberty Ship SS George Ade was named in his honor.

Selected published works

- "Stories of the Streets and of the Town" (a series of newspaper columns published from 1894 to 1900)[5]

- What a Man Sees Who Goes Away from Home (1896)[33]

- Circus Day [1896][34]

- Artie (1896)[2]

- Pink Marsh (1897)[2]

- Doc' Horne (1899)[35]

- Fables in Slang (New York, 1900)[36]

- More Fables (1900)[37]

- American Vacations in Europe (1901)[38]

- Forty Modern Fables (1901)[39]

- The Girl Proposition (1902)[2]

- The Sultan of Sulu (1902–03), a comic opera and a one-act play[40]

- Peggy from Paris (1903), a musical comedy[41]

- The County Chairman (1903 and 1924), a play[42]

- In Babel (1903)[43]

- People You Know (1903)[2]

- Handsome Cyril (1903,Strenuous Lad's Library, no. 1)[44]

- Clarence Allen (1903, Strenuous Lad's Library, no. 2)[45]

- Rollo Johnson (1904, Strenuous Lad's Library, no. 3[46]

- Breaking into Society (1904)[2]

- The Sho-Gun (1904), a comic opera[2]

- The College Widow (1904 and 1924), adapted as Leave It to Jane, a musical by Jerome Kern, Guy Bolton, and P. G. Wodehouse in 1917.[7]

- True Bills (1904)[2]

- The Bad Samaritan (1905), a play[47]

- Just Out of College (1905 and 1924), a play[48][5]

- In Pastures New (1906)[2]

- Marse Covington (1906), a one-act play[49]

- Round about Cairo, with and without the Assistance of the Dragoman or Simon Legree of the Orient (1906), from In Pastures New[50]

- The Slim Princess (1907)[2]

- The Fair Co-ed (1908), a musical[47]

- Father and the Boys (1908), a comedy-drama play[51][52]

- The Old Town (1910), a musical[50][47]

- I Knew Him When: A Hoosier Fable Dealing with the Happy Days of Away Back Yonder (1910)[53]

- Hoosier Hand Book and True Guide for the Returning Exile (1911)[54]

- Verses and Jingles (1911)[55]

- On the Indiana Trail (1911)[56]

- The Revised Legend for One Who Came Back (1912)[5]

- Knocking the Neighbors (1912)[55]

- Ade's Fables (1914)[57]

- The Fable of the Busy Business Boy and the Droppers-In (1914)

- The Fable of the Roistering Blades (1915)

- Invitation to You and Your Folks from Jim and Some More of the Home Folks (1916)[58]

- Hand-made Fables (1920)[59]

- Single Blessedness and Other Observations (1922)[60]

- Mayor and the Manicure (1923), a one-act play[61]

- Nettie (1923), a one-act play[62]

- Speaking to Father (1923), a one-act play[5]

- Thirty Fables in Slang (1926; reprinted in 1933)[63]

- Bang! Bang! (1928)[64]

- Old-time Saloon: Not Wet—Not Dry, Just History (1931)[65]

- One Afternoon with Mark Twain (1939)[66]

- Notes & Reminiscences (with John T. McCutcheon) (1940)[67]

Collected works

- The America of George Ade, 1866–1944; Fables, Short Stories, Essays (1960, edited and introduced by Jean Shepherd)

- Stories of the Streets and of the Towns (1941, edited by Franklin J. Meine)

Film adaptations

- The County Chairman (1914)

- The Fable of the Busy Business Boy and the Droppers-In (short, 1914)

- The Slim Princess (1915)

- Father and the Boys (1915)

- The College Widow (1915)

- Marse Covington (1915)[68]

- The Fable of the Roistering Blades (short, 1915)

- Just Out of College (1920)[69]

- The Slim Princess (1920)

- The Fair Co-Ed (1927)

- The College Widow (1927)

- The County Chairman (1935)

- Freshman Love (1936), an adaption of The College Widow[70]

- Part of Till the Clouds Roll By (1946), which includes two songs adapted from The College Widow

Other

- "Authors!—Burn Up Your Alibis!," Photoplay, September 1923, p. 46.

- The Sigma Chi Creed (1929)

In fiction

- Ade journeys to Mars with Nikola Tesla and Mark Twain in Sesh Heri's novel Wonder of the Worlds (2005).[citation needed]

- P. G. Wodehouse refers to Ade's "The Fable of the Author Who Was Sorry for What He Did to Willie" in Love Among the Chickens (1909).[71]

References

- ^ a b Johnson 1906, p. 58

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Leonard, John William; Marquis, Albert Nelson, eds. (1908). Who's who in America. Vol. 5. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who, Incorporated. p. 13.

- ^ Boomhower, Ray E. (2000). Destination Indiana: Travels Through Hoosier History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 60. ISBN 0871951479.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Biographical Sketch" in Mendes, Joanne, compiler (2007). A Guild to the George Ade Papers (PDF). West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections. pp. 7–10.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Banta, R. E., compiler (1949). Indiana Authors and Their Books, 1816–1916, biographical sketches of authors who published during the first century of Indiana statehood with lists of their books. Crawfordsville, Indiana: Wabash College. pp. 3–4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Gugin, Linda C.; James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

- ^ a b c d Matson, Lowell (1962). Ade: Who Needed None. p. 9. OCLC 10291088.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Inventory of the George Ade Papers, 1865–1971: Biography of George Ade". The Newberry. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ Matson, p. 12.

- ^ Matson, p. 14.

- ^ Coyle, p. 53

- ^ Dietz, p. 57-58

- ^ Franceschina, John (2018). "Wathall, Alfred G[eorge]". Incidental and Dance Music in the American Theatre from 1786 to 1923, Volume 3: Biographical and Critical Commentary - Alphabetical Listings from Edgar Stillman Kelley to Charles Zimmerman. BearManor Media.

- ^ Mendoza, Victor Román (December 17, 2015). "Chapter IV; The Sultan of Sulu 's Epidemic of Intimacies". Metroimperial Intimacies: Fantasy, Racial-Sexual Governance, and the Philippines in U.S. Imperialism, 1899-1913. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822374862.

- ^ Bordman, Gerald Martin (1982). American Musical Comedy: From Adonis to Dreamgirls. Oxford University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780195031041.

- ^ Dietz, p. 138-140

- ^ a b Matson, pp. 18 and 22.

- ^ a b c d e f "Author's Northern Indiana Home Prepares for Next Chapter: A Rural Retreat". Indiana Landmarks. January 23, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Gugin and St. Clair, eds., pp. 4–5.

- ^ Matson, pp. 23–24 and 26.

- ^ Matson, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e Shumaker, Arthur, "George Ade," in Greasley, Philip A. (2001). Dictionary of Midwestern Literature. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0-253-33609-0.

- ^ Sante, Luc (February 9, 2011). "George Ade". HILOBROW. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ Excerpt from "The Fable Of The Slim Girl Who Tried To Keep A Date That Was Never Made" in Ade, George (1899). Fables in Slang. Chicago: Herbert S. Stone and Company. (via Project Gutenberg)

- ^ Coyle, p. 7

- ^ "Introduction" in Kelly, Fred (1947). The Permanent Ade: The Living Writings of George Ade. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill Company. OCLC 1075682.

- ^ a b c d Boomhower, pp. 63–64.

- ^ "Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved June 10, 2019. Note: This includes George R. Funk (November 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: George Ade House" (PDF). Retrieved June 10, 2019. and Accompanying photographs.

- ^ a b "Biographical Sketch" in Emily Castle (2006). George Ade Letter, 6 may 1923 Collection Guide (PDF). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society.

- ^ a b Kelly, Fred (1947). George Ade, Warmhearted Satirist. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill Company. pp. 264–65. OCLC 606708.

- ^ a b Kelly, George Ade, Warmhearted Satirist, p. 266.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Russo, Dorothy Ritter (1947). A Biography of George Ade, 1866–1944. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 14. OCLC 1059626.

- ^ Russo, p. 16.

- ^ Russo, p. 28.

- ^ Russo, p. 30.

- ^ Russo, p. 36.

- ^ Russo, p. 129.

- ^ Russo, p. 38.

- ^ Russo, pp. 45–48 and 53.

- ^ Matson, p. 20.

- ^ Russo, pp. 97–98

- ^ Russo, p. 59.

- ^ Russo, p. 55.

- ^ Russo, p. 57

- ^ Russo, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Matson, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Russo, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Russo, p. 85.

- ^ a b Russo, p. 71.

- ^ Russo, pp. 95–96.

- ^ "George Ade". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Russo, p. 76.

- ^ Russo, p. 77.

- ^ a b Russo, p. 78.

- ^ Russo, p. 133.

- ^ Russo, p. 83.

- ^ Russo, p. 84.

- ^ Russo, p. 86.

- ^ Russo, p. 88.

- ^ Russo, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Matson, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Russo, p. 53.

- ^ Russo, pp. 100–1.

- ^ Russo, p. 102.

- ^ Russo, p. 104.

- ^ Russo, p. 105.

- ^ Carewe, Edwin (July 12, 1915), Marse Covington (Drama), Edward Connelly, Louise Huff, John J. Williams, Rolfe Photoplays, retrieved September 21, 2024

- ^ Green, Alfred E. (November 27, 1920), Just Out of College (Comedy), Jack Pickford, Molly Malone, George Hernandez, Goldwyn Pictures Corporation, retrieved September 21, 2024

- ^ Matson, p. 8.

- ^ Wodehouse wrote: "The whole thing began like Mr. George Ade's fable of the author. An author — myself — was sitting at his desk trying to turn out something that could be converted into breakfast food, when a friend came in and sat down on the table and told him to go right on and not mind him." (Chapter XII, Love Among the Chickens) Wodehouse also wrote: "I felt, like the man in the fable, as if some one had played a mean trick on me, and substituted for my brain a side order of cauliflower." (Chapter XVILove Among the Chickens) Wodehouse makes a reference to the "mean trick" again in Mike (1909): "But that Adair should inform him, two minutes after Mr. Downing's announcement of Psmith's confession, that Psmith, too, was guiltless, and that the real criminal was Dunster — it was this that made him feel that somebody, in the words of an American author, had played a mean trick on him, and substituted for his brain a side-order of cauliflower." (Chapter LVIII, Mike)

Sources

- "Author's Northern Indiana Home Prepares for Next Chapter: A Rural Retreat". Indiana Landmarks. January 23, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- "Biographical Sketch" in Castle, Emily (2006). George Ade Letter, 6 May 1923 Collection Guide (PDF). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society.

- "Biographical Sketch" in Mendes, Joanne (compiler) (2007). A Guild to the George Ade Papers (PDF). West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections. pp. 7–10.

- Boomhower, Ray E. (2000). Destination Indiana: Travels Through Hoosier History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. pp. 58–65. ISBN 0871951479.

- Coyle, Lee (1964). George Ade. New York: Twayne Publisher, Inc. OCLC 1087895012.

- Dietz, Dan (2022). The Complete Book of 1900s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781538168943.

- Gugin, Linda C.; St. Clair, James E., eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

- "Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved June 10, 2019. Note: This includes Funk, George R. (November 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: George Ade House" (PDF). Retrieved June 10, 2019.

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Ade, George". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. p. 58.

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Ade, George". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. p. 58.- Kelly, Fred (1947). George Ade, Warmhearted Satirist. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill Company. OCLC 606708.

- Kelly, Fred (1947). The Permanent Ade: The Living Writings of George Ade. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill Company. OCLC 1075682.

- Leonard, John William; Marquis, Albert Nelson, eds. (1908). Who's who in America. Vol. 5. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who, Incorporated. p. 13.

- Matson, Lowell (1962). Ade: Who Needed None. OCLC 10291088.

- Russo, Dorothy Ritter (1947). A Biography of George Ade, 1866–1944. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. OCLC 1059626.

Further reading

- Coyle, Lee (1964). George Ade. Twayne's United States Authors Series. New Haven College and University Press. OCLC 1087895012.

- DeMuth, James (1980). Small Town Chicago: The Comic Perspectives of Finley Peter Dunne, George, Ade, and Ring Lardner. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 9780804692526.

External links

- George Ade at the Internet Broadway Database

- Works by George Ade at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about George Ade at the Internet Archive

- Works by George Ade at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- George Ade at IMDb

- Over 150 George Ade stories read in Mister Ron's Basement Podcast, now indexed to make them easy to find

- George Ade Digital Exhibit at Purdue University Libraries The Libraries Archives and Special Collections holds many of Ade's original works.

- George Ade Papers 1865–1971 at The Newberry Library