Georg Eberhard Rumphius

Georg Eberhard Rumphius (originally: Rumpf; baptized c. 1 November 1627 – 15 June 1702) was a German-born botanist employed by the Dutch East India Company in what is now eastern Indonesia, and is best known for his work Herbarium Amboinense produced in the face of severe personal tragedies, including the death of his wife and a daughter in an earthquake, going blind from glaucoma, loss of his library and manuscripts in major fire, and losing early copies of his book when the ship carrying it was sunk.

Early life

Rumphius was the oldest son of August Rumpf, a builder and engineer in Hanau, and Anna Elisabeth Keller, sister of Johann Eberhard Keller, governor of the Dutch-speaking Kleve (Cleves), at that time a district of the Electorate (Kurfürstentum) of Brandenburg. Around 1 November 1627, he was baptized Georg Eberhard Rumpf in Wölfersheim, likely indicating he was born in October 1627. He grew up in Wölfersheim and attended the Gymnasium in Hanau.

Although born and raised in Germany, he spoke and wrote in Dutch from an early age, probably as learned from his mother. He was recruited by the West India Company, ostensibly to serve the Republic of Venice, but was put on a ship "De Swarte Raef" (The Black Raven) in 1646 bound for Brazil where the Dutch and Portuguese were fighting over territory. Either through shipwreck or capture he landed in Portugal, where he remained for nearly three years. Around 1649 he returned to Hanau where he helped his father's business.[1]

Merchant of Ambon

A week after his mother's funeral (20 December 1651) he left Hanau for the last time. Perhaps through contacts of his mother's family, he enlisted with the Dutch East Indies Company (as Jeuriaen Everhard Rumpf) and left as a midshipman on 26 December 1652 aboard the ship Muyden for the Dutch East Indies. He arrived in Batavia in July 1653, and proceeded to the Ambon archipelago in 1654. By 1657 his official title was "engineer and ensign", at which point he requested a transfer to the civilian branch of the company and became second merchant ("onderkoopman") on Hitu island, north of Ambon. He became a merchant ("koopman") in 1662. He then started to undertake a study of the flora and fauna of these Spice Islands. In 1666 he was appointed as "secunde" at Ambon directly under Joan Maetsuycker, the governor-general in Batavia, who would later give him dispensation from his ordinary duties to complete this study. Maetsuycker was a barrister-at-law and a patron of science. Rumphius would become known as Plinius Indicus (the Pliny of the Indies).[1] This was the name under which he was made a member by the Academia Naturae Curiosorum in Vienna in 1681.[2]

Herbarium Amboinense

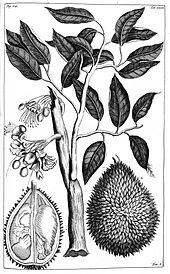

Rumphius is best known for his authorship of Het Amboinsche kruidboek or Herbarium Amboinense, a catalogue of the plants of the island of Amboina (in modern-day Indonesia), published posthumously in 1741. The work covers 1,200 species, 930 with definite species names, and another 140 identified to genus level.[3] The publication of this book was possible because of the governor Johannes Camphuys. Camphuys, an amateur astronomer, personally reviewed the manuscript and ensured a copy was made before the ill-fated manuscript was sent off to Europe for printing. Rumphius provided illustrations and descriptions for nomenclature types for 350 plants, and his material contributed to the later development of the binomial scientific classification by Linnaeus.[4] His book provided the basis for all future study of the flora of the Moluccas and his work is still referred to today.[4] Despite the distance, he was in communication with scientists in Europe, was a member of a scientific society in Vienna, and even sent a collection of Moluccan sea shells to the Medicis in Tuscany.

After going blind in 1670 due to glaucoma, Rumphius continued work on his six-volume manuscript with the help of others. His wife and a daughter were killed by a wall collapse during a major earthquake and tsunami on 17 February 1674. On 11 January 1687, with the project nearing completion, a great fire in the town destroyed his library, numerous manuscripts, original illustrations for his Herbarium Amboinense, volumes of the Hortus Malabaricus, and works by Jacobus Bontius.[1] Persevering, Rumphius and his helpers first completed the book in 1690, but the ship carrying the manuscript to the Netherlands was attacked and sunk by the French, forcing them to start over from a copy that had fortunately been retained thanks to Camphuys.[2] The Herbarium Amboinense finally arrived in the Netherlands in 1696. However, the East India Company decided that it contained so much sensitive information that it would be better not to publish it.[5] Rumphius died in 1702, so he never saw his work in print; the embargo was lifted in 1704, but then no publisher could be found for it. It finally appeared in 1741, thirty-nine years after Rumphius's death, in a Latin translation by Johannes Burman (1707–79).[6][7] Much of the natural history in Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën ("Old and New East-India") by François Valentijn was by Rumphius and they were close friends.

The original manuscript of Het Amboinsch Kruidboek (MS BPL 314) is held at Leiden University Libraries and a digital version is available in its Digital Collections.[8]

The Herbarium Amboinense as published in 1741 consisted of six large folio volumes. Being blind, Rumphius required the assistance of others to produce it. His wife, Suzanna, was one of the early assistants and she was commemorated in Flos Susannae a white orchid (now Pecteilis susannae) described by Rumphius. His son Paul August made many of the plant illustrations as also the only known portrait of Rumphius. Other assistants included Philips van Eyck, a draughtsman, Daniel Crul, Pieter de Ruyter a soldier trained by Van Eyck, Johan Philip Sipman, Christiaen Gieraerts J. Hoogeboom[1] An English translation by E. M. Beekman, which took seven years to make, was posthumously published in 2011.[9]

Among the many species described in the Herbarium was the upas tree (Antiaris toxicaria); the toxicity of the tree was exaggerated and caught the fancy of Europeans.[10] Other plants included a description of the clove, the starfruit and durian. Rumphius used multinomial names and his descriptions were largely missed by Linnaeus as he received it after he had worked on Species Plantarum.[9] Rumphius was the first to interpret the function of the pitchers in pitcher plants. He also discovered that some mosquitoes bred in their pools. He analysed edible nest swiftlets and came to the conclusion that the substance was produced by the swiftlets and not marine algae as had been earlier believed.[2]

The other major work D'Amboinsche Rariteitkamer ("Amboinese Cabinet of Curiosities"), a manuscript he had sent to Dr Hendrik D'Acquet of Delft in 1701 consisted mainly of plates of seashells and crabs.[6]

After Rumphius' death, his son Paul August was appointed "merchant of Amboina", the position his father had held. A monument was erected to the memory of Rumphius at Amboina but this was destroyed by the English who believed they would find gold under it. In 1824 a second monument was built by Governor-General van der Capellen but this was destroyed by a bomb in World War II.[1]

Works

- Schijnvoet, Simon, ed. (1705). D'Amboinsche Rariteitkamer: Behelzende eene beschryvinge van allerhande zoo weeke als harde Schaalvisschen, te weeten raare Krabben, Kreeften, en diergelyke Zeedieren, als mede allerhande Hoorntjes en Schulpen, die men in d'Amboinsche Zee vindt (in Dutch). T'Amsterdam: gedrukt by François Halma boekverkoper.

- Beekman, Eric Montague, ed. (1999). The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet (in Dutch and English). Translated, edited, annotated, and with an introduction. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07534-0.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1741). Het Amboinsche kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 1. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Jan Catuffe, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1741). Het Amboinsche kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 2. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Jan Catuffe, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1743). Het Amboinsch kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 3. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Jan Catuffe, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1743). Het Amboinsch kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 4. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Jan Catuffe, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1747). Het Amboinsch kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 5. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1750). Het Amboinsch kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 6. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Amboinsch Kruid-boek. Auctuarium (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Meyndert Uytwerf (2.). 1755.

- Amboinsche Historie (Amboina History)

- Amboinsche Lant-beschrijvinge (a social geography)

- Amboinsch Dierboek (Amboina animal book, lost)

References

- ^ a b c d e de Wit, H.C.D. (1952). "In Memory of G. E. Rumphius (1702-1952)". Taxon. 1 (7): 101–110. doi:10.2307/1217885. JSTOR 1217885.

- ^ a b c Meeuse, B.J.D. (1965). "Straddling two worlds: A biographical sketch of Georg Everhard Rumphius, Plinius Indicus". The Biologist. 68 (3–4): 42–54.

- ^ Merrill, Elmer D. (1 Nov 1917). An Interpretation of Rumphius's Herbarium Amboinense. Vol. Publication No. 9. Manila, Philippines: Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Bureau of Science. pp. 1–595.

- ^ a b Monk, K.A.; Fretes, Y.; Reksodiharjo-Lilley, G. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 4. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

- ^ "museumboerhaave.nl". Archived from the original on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ^ a b Sarton, George (1937). "Rumphius, Plinius Indicus (1628-1702)". Isis. 27 (2): 242–257. doi:10.1086/347243. S2CID 144849243.

- ^ Baas, Pieter and Jan Frits Veldkamp (2013). "Dutch pre-colonial botany and Rumphius's Ambonese Herbal" (PDF). Allertonia. 13: 9–19.

- ^ "Digital version of G.E. Rumphius, Amboinsch Kruidboek, boeken I-XII, met het Auctuarium of Toegift - BPL 314". Leiden University Libraries. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ a b Margulis, Lynn; Peter Raven (2009). "Macroscope: The Herbal of Rumphius". American Scientist. 97 (1): 7–9. doi:10.1511/2009.76.7.

- ^ Bastin, John (1985). "New light on J.N. Foersch and the celebrated poison tree of Java". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 58 (2): 25–44.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Rumph.

Sources

- Wehner, U., W. Zierau, & J. Arditti The merchant of Ambon: Plinius Indicus, in Orchid Biology: Reviews and Perspectives, pp 8–35. Tiiu Kull, Joseph Arditti, editors, Springer Verlag 2002

- Georg Eberhard Rumpf and E.M. Beekman (1999). The Ambonese curiosity cabinet - Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, Yale University Press (New Haven, Connecticut): cxii + 567 p. (ISBN 0300075340) English translation preceded by an account of his life and work and with annotations.

External links

Media related to Georg Eberhard Rumpf at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Georg Eberhard Rumpf at Wikimedia Commons- An interpretation of Rumphius's Herbarium amboinense (1917) by E.D. Merrill

- Rumphius Gedenkboek (1902) [="Rumphius memorial book" in Dutch]

- Rumpf, George Eberhard (1741) D'Amboinsche rariteitkamer - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library