Geography of Mesoamerica

The geography of Mesoamerica describes the geographic features of Mesoamerica, a culture area in the Americas inhabited by complex indigenous pre-Columbian cultures exhibiting a suite of shared and common cultural characteristics. Several well-known Mesoamerican cultures include the Olmec, Teotihuacan, the Maya, the Aztec and the Purépecha. Mesoamerica is often subdivided in a number of ways. One common method, albeit a broad and general classification, is to distinguish between the highlands and lowlands. Another way is to subdivide the region into sub-areas that generally correlate to either culture areas or specific physiographic regions.

Geographic location

Mesoamerica – meaning "middle of America" – is located in the mid-latitudes (between 10° and 22° N) of the Americas in the southern portion of North America, encompassing much of the isthmus that joins it with South America. Situated within the wider region known as Middle America,[1] Mesoamerica extends from south-central Mexico southeastward to include the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Yucatán Peninsula, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and the Pacific coast of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica down to the Gulf of Nicoya.

The term Mesoamerica may occasionally refer to the contemporary region comprising the nine southeastern states of Mexico (Campeche, Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz, and Yucatán) and the countries of Central America (including Panama).[2]

Physiography

The region possesses a complex combination of ecological systems. Archaeologist and anthropologist Michael D. Coe grouped these different niches into two broad categories: lowlands (those areas between sea level and 1000 meters) and altiplanos or highlands (those situated between 1000 and 2000 meters above sea level). In the low-lying regions, sub-tropical and tropical climates are most common, as is true for most of the coastline along the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. The highlands show much more climatic diversity, ranging from dry tropical to cold mountainous climates, the dominant climate is temperate with warm temperatures and moderate rainfall.

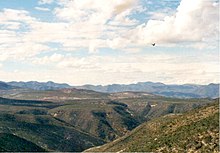

Highlands

The highlands of Mesoamerica generally contain two separate regions: the mountainous zone of central and western Mexico, and the highlands of Guatemala and the Mexican state of Chiapas. The topography, climate, and soil fertility of the highlands can vary dramatically. In central and western Mexico, the most fertile soil is found among the low-lying valleys. Several of these, including the Valley of Oaxaca, Puebla-Tlaxcala, and the Valley of Mexico (now Mexico City), were historically important locations where complex pre-Columbian societies developed. The tall mountainous peaks of the Sierra Madres, however, impedes the movement of clouds and reduces the amount of rainfall the region receives. Indeed, the hot arid valleys of the Mixtec area and in the state of Guerrero are among two of the driest areas in the highlands.

Initial hypotheses concerning environmental conditions postulated that the highland climate was more hospitable in the past.[citation needed] More recent research has made it clear that the climate past was not very different from that of today, even though the ecosystems do show a significant degree of decline due to human activity.[citation needed] Many parts of the highlands show evidence of early deforestation, and various species have disappeared from their former habitats.[citation needed]

The highlands of Mesoamerica, while not extraordinarily rich, Were sufficiently fertile to allow the development of the high agricultural cultures of ancient, pre-Hispanic times.[citation needed] In fact, the situation was quite similar to that of other regions of the world where early civilizations thrived, as in the north of Peru, or in the valley of the Indus River in Asia.[citation needed] In these sites, as in Mesoamerica, humans developed methods in which the limited available resources could be fully exploited. Highland agrarian cultures learned to store water or divert it from its sources in the mountains to the cultivable lands.[citation needed] One of the most well-known adaptations was the use of chinampas, or artificial islands upon which plants could be cultivated. Chinampas were originally used by the Purépechas in western Guerrero and by the Aztec in the Valley of Mexico. Several chinampas still survive in Xochimilco.

The lowlands, however, offered a great variety of usable flora and fauna resources. These included resources that could not only be consumed in lieu of full-scale agriculture, but also traded to obtain other goods. Furthermore, the greater accessibility of the coast facilitated transportation, interregional communication, and trade.

Cultural areas

Mesoamerica as a whole is considered a culture area within which a number of cultural sub-areas existed. While all cultures in Mesoamerica share a number of common characteristics, cultural sub-areas are defined by a higher level of specificity in defining elements (i.e., classification of cultural sub-areas is based on more specific criteria than the more broadly defined Mesoamerica). The sub-areas generally correlate with known cultural groups, such as the areas where the Maya, Huastec, and Olmec were found, for example. This is not to say that all the peoples in an area share a common ethnicity (indeed, in many cases they do not even share the same language) or lived within or under a single polity. At the same time, based on cultural similarities, it is clear that various kinds of interaction occurred within sub-areas, be them historical relationships, political interaction (e.g., alliances, conflict), and/or economic or commercial agreements. Listed below are the sub-areas found in Mesoamerica.

Considerable research has been conducted about regional communications in ancient Mesoamerica. There were apparent trade routes starting in the Mexico Central Plateau, and going down to the Pacific coast. These contacts then went on as far as Central America. These trade networks operated with various interruptions from the earliest times and up to the Late Classical Period (600–900 CE).

Central Mexico

One of the most important areas in the pre-Columbian history of Mexico is known as 'Central Mexico'. This area is composed of moderate to cold valleys in the southern part of the Mexican high plateau and in the north of the Balsas River basin. It is an ecological niche characterized by its temperate climate and absence of significant water sources. The rains arrive between the months of April and September, and are not abundant. This led to the early development of hydraulic projects, among them the building of canals from the rivers–reservoirs in the hillsides for storing water.

The valley of Tehuacá, located in the southeast of this region, is important for the early evidence of maize cultivation and some of the oldest ceramic artifacts (sherds) in Mesoamerica. The Valley of Mexico, location of Lake Texcoco, was the home for several important cultures, including Cuicuilco, Teotihuacan, Tula (Toltec), and the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.

Maya Region

The Mayan Region is the largest in Mesoamerica. As such, it encompasses a vast and varied landscape, from the mountainous regions of the Sierra Madre to the semi-arid plains of northern Yucatán. Climate in the Maya region can vary tremendously, as the low-lying areas are particularly susceptible to the hurricanes and tropical storms that frequent the Caribbean. The region is generally divided into three loosely defined zones: the southern Maya highlands, the southern (or central) Maya lowlands, and the northern Maya lowlands. The southern Maya highlands include all of elevated terrain in Guatemala and the Chiapas Highlands. The southern lowlands lie just north of the highlands, and incorporate the Petén of northern Guatemala, Belize, and the southern portions of the Mexican states of Campeche and Quintana Roo. The northern lowlands cover the remainder of the Yucatán Peninsula, including the Puuc hills. Geologically, the Maya region consists of a limestone plateau that rises slightly toward the south, ending where the mountainous zone interrupts the plain.

Northern Maya lowlands

The climate of the northern Maya lowlands can vary greatly. The northwestern part of the peninsula is considered semi-arid and one of the driest in the Maya region, while the northeast receives a greater amount of rainfall. There is an overall lack of surface water in the northern lowlands, though cenotes are common and provide a source of water. Generally, the water table (or aquifer) is not particularly deep, and the excavation of wells is possible once the bedrock cap is pierced. With the exception of the Puuc hills, which range from central and southern Yucatán into the northern parts of Campeche, there is little topographic variation in the lowlands.

Southern Maya lowlands

The southern lowlands receive much more rainfall and, climatically, contain tropical and sub-tropical zones. Rivers, such as the Usumacinta and the Pasion, originate in the highlands and pass through several areas of the southern lowlands. In contrast to the north, there are a number of lakes in the southern lowlands, such as Lake Petén Itza.

Southern Maya highlands

Unlike the highland regions of central Mexico, the southern Maya highlands are generally cool, temperate in climate, and covered in thick vegetation. The eastern portions of the highlands are somewhat drier. The Sierra Madre mountains are volcanic, and Tajumulco Volcano, at an elevation of 4,220 m (13,845 ft), is the highest point in Central America. The highlands of Guatemala has a total of 37 volcanoes, four of which are active (Pacaya, Santiaguito, Fuego and Tacaná). Earthquakes are frequent, and flooding and mudslides occur.

Oaxaca

The Oaxacan region has been one of the most diverse since the Mesoamerican epoch. It is a completely mountainous territory, marked by the Sierra Madre del Sur and the Mixteca shield. It includes a portion of the Balsas River basin, characterized by its dryness and complicated geographical relief. Its river beds are shallow and of small capacity. In this sense, it appears much like Central Mexico.

There were two principal scenarios in the cultural history of the Oaxacan people. On the one hand, the central Valley of Oaxaca saw the development of the Zapotec culture, one of the most ancient and well known of the Mesoamerican region. This culture was developed by the chiefdoms that controlled the arable land (which was very fertile, albeit dry) of the small valleys of Etla, Tlacolula, and Miahuatlán. Some of the first examples of great architecture in Mesoamerica were in this region, for example, the ceremonial center of San José Mogote. The hegemony of this center in the Valley region passed into the hands of Monte Albán, the Classic capital of the Zapotec. The fall of Teotihuacán in the 8th century CE permitted the great heights achieved by the Zapotec culture. However, the city of Monte Albán was abandoned in the 10th century CE, and gave way to a series of regional centers that fought among each other for political dominance.

The other principal scenario was that of the Mixtec region, which lies to the west of the Central Valley. The Mixtec region has also been occupied since prehistoric times. It has an extremely mountainous terrain of variable altitude, rising to more than 3,000 metres (9,800 ft). The climate varies from mountainous and temperate to tropical and dry, and rain is generally scarce. There is little running surface water, and presently, a good part of the area has become alarmingly deforested, a result of the ground-clearing agricultural practices of the ancient inhabitants of the region.

By the Preclassic period there were already important population centers in the region, such as Yucuita and Cerro de las Minas. However, the Mixtec capitals did not reach the magnitude of their Zapotec neighbors. The summit of the Mixtec culture was reached in the Postclassic period, when Lord 8 Deer of Tututepec and Tilantongo embarked on a campaign of political unification of the Mixtec city-states, and came to occupy the Central Valley of Oaxaca.

Guerrero

Guerrero has traditionally been considered part of Western Mexico. However, recent discoveries have reoriented the divisions of the Mesoamerican cultural areas, and in the works of recent authors, Guerrero is regarded as an independent cultural area. The Guerrero region occupies approximately the area of the southern Mexican state of the same name. It can be divided into three regions with different characteristics: in the north, the Basin of the Balsas River, whose current is the defining characteristic of the regional geography. The Balsas Basin is a low-lying region, with a hot climate and scarce rainfall, whose dryness is mitigated by the presence of the Balsas River and its numerous branches. Central Guerrero corresponds to the Sierra Madre del Sur, a region rich in mineral deposits but poor in agricultural potential. Lastly, the southern part of the region consists of the Pacific coast, a wide coastal plain, full of mangroves and palms, battered by hurricanes from the south.

Guerrero was the site of the first pottery traditions in Mesoamerica. The most ancient remains have been found in Puerto Marqués, near Acapulco, and are about 3500 years old. During the Preclassic period, the Balsas Basin became an area of vital importance for the cultural development of the Olmec, who left signs of their presence in areas such as Teopantecuanitlán and the grottos of Juxtlahuaca. Later came the development of a sculptural tradition known as Mezcala, characterized by its geometrization of the human form. During the Postclassic period, the greater part of Guerrero remained under the domination of the Mexica, and only the Tlapanec lands of Yopitzinco remained independent.

The West

Western Region is one of the least known areas of Mesoamerica. It is an extensive region that comprises the slopes of the Sierra Madre Occidental, a part of the Sierra Madre del Sur and the middle and lower basin of the Lerma River. The foothills of the mountain were covered by forests of pine and oak, but forestry in the area has reduced its size. The land is suited to cultivation due to its fertility and abundant water resources, especially in the coastal plain of Sinaloa, the Bajío, and the Tarascan Plateau. The climate varies from cold in the mountains, in the east of Michoacán, to tropical along the coast of Nayarit.

This region was inhabited by Uto-Aztecan-speaking peoples, such as the Cora, the Huichol, and the Tepehuano. The incorporation of these peoples into the sphere of Mesoamerican civilization was very gradual, and it is presumed that the first ceramics developed in this region were linked to traditions of the Andean people of Ecuador and Peru. The changes that clearly affected the rest of the region are less observable in the West, and for that reason, the cultural traditions of the Preclassic period, such as those of the Colima, Jalisco and Nayarit, or those of the tumbas de tiro survived well into the Classic period (150–750 CE). The best known of the western societies is the Purépecha, which rivaled the power of the Mexica during the 15th century CE.

The North

The North of Mesoamerica formed part of the cultural super area only during the Classic era (150-750 CE), during which Teotihuacan's apogee, and population growth, favored migration towards the north and commerce with distant Oasisamerica. The region is flat, compressed between the mountain ranges of the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Sierra Madre Oriental. The climate is dry, if not desert-like, with scarce vegetation, for which reason agriculture was only possible through the canalization of surface water currents (especially the Pánuco River and the Lerma tributaries) and the storage of rain water. The excessive dependence on good weather led the people of the North to abandon the region in the middle of the 8th century after enduring a prolonged drought and invasions of Aridoamerican people.

The centers of population in the North were dependent on the network of commerce that was established between Teotihuacan and the Oasis America societies. Sites such as La Quemada in Zacatecas, and La Ferrería in Durango served as forts to guard the commercial routes. When agriculture and the social system collapsed in the North, the occupants of the region migrated towards the West, the Gulf, and the Center of Mexico.

Centroamerica

The area known as Centroamerica occupies the Pacific coasts of El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica. The climate of this region is tropical, with important geological activity, and includes the great Mediterranean lakes of Central America: Lake Nicaragua and Lake Managua. As in the case of the northern region, Centroamerica formed part of the Mesoamerican world only temporarily. It is customary to count the Centroamerican peoples as part of the transition zone between the Andean world and Mesoamerica. Their first contact with the center of Mesoamerica occurred in the Preclassic period, as indicated by the Olmec influence in the area. However, in the Classic period relations were interrupted and Centroamerica received significant cultural influences from the Colombian Altiplano. The development of metallurgy in Centroamerica, for example, occurred much earlier than in the rest of Mesoamerica. During the Postclassic period, the area was again part of the Mesoamerican sphere, as Pipil and Nicarao people, both speakers of Nawat, migrated to this area during the time of the Toltec Empire. Speakers of Subtiaba and Mangue are also thought to have migrated to the area from Mesoamerica proper, though the circumstances of such a migration remain unclear.

See also

Sources

- ^ Dow, James W. 1999. The Cultural Anthropology of Middle America Archived 2007-07-04 at the Wayback Machine: "Mesoamerica is a sub-area of Middle America ..."

- ^ OECD. 2006. OECD Territorial Reviews: The Mesoamerican Region: Southeastern Mexico and Central America (ISBN 92-64-02191-4). Retrieved 24 February 2007.