Genetic studies on Sami

Genetic studies on Sami is the genetic research that have been carried out on the Sami people. The Sami languages belong to the Uralic languages family of Eurasia.

Siberian origins are still visible in the Sámi, Finns and other populations of the Finno-Ugric language family.[2]

An abundance of genes has journeyed all the way from Siberia to Finland.[3] As late as the Iron Age, people with a genome similar to that of the Sámi people lived much further south in Finland compared to today. The first study on the DNA of the ancient inhabitants of Finland has been published, with results indicating that a copious number of Siberian genetic variants are present in modern Sami populations.

Genetic material from remains associated with Neo-Siberians has been found in the inhabitants of the Kola Peninsula from as far back as approximately 4,000 years ago, later spreading also to Finland. The study also corroborates the assumption that people genetically similar to the Sámi lived much further south than currently. Neo-Siberian populations diverged from East Asian people >11,000 years ago and expanded into Siberia, where they mixed with and replaced the previous Paleosiberian peoples. The spread of early Neo-Siberian ancestry westwards may be associated with the dispersal of Uralic languages.[4][5]

The genetic samples compared in the study were collected from human bones found in a 3,500-year-old burial place in the Kola Peninsula and the 1,500-year-old lake burial site at Levänluhta in South Ostrobothnia, Finland. All of the samples contained identical Siberian genes.

Y-DNA

Three Y chromosome haplogroups dominate the distribution among the Sami: N1c (formerly N3a), I1 – today more commonly known as I-M253 – and R1a, at least in the study carried out by K. Tambets et al. in 2004. The most common haplogroup among the Sami is N1c, with I1 as a close second according to that study. Haplogroup R1a in Sami is mostly seen in the Swedish Sami and Kola Sami populations, with a low level among the Finnish Sami according to Tambets and colleagues, a finding that suggests that N1c and R1a probably reached Fennoscandia from eastern Europe, where these haplogroups can be found in high frequencies.[6] In Finland there is also a general difference within the Finnish population between eastern and western Finland, where eastern show a dominance of N-haplogroup and the west a dominance of I-haplogroup, where the latter is explained by a migration from southern parts of today's Norway and Sweden over to Finland as we know it today.[citation needed]

But the spread of R1a-haplogroup amongst Sami in Sweden shows a big span from 10.1% to 36.0%, with an average of 20%, to be compared with Sami in Finland with a span from 9% to 9.9%[6] Because Sami groups in Sweden show differences between haplogroups – such as U5b and V even thought that are mtDNA-groups – in the south of Sweden and in the north of the country (see below), the spread of Y-haplogroups such as R1a amongst groups of Sami in Sweden might be significant as well. No such study has yet been done though.

However the two haplogroups R1a and N1c have a distinctly distribution when it comes to linguistic. R1a is common among Eastern Europeans speaking Indo-European languages, while N1c correlates closely with the distribution of the Finno-Ugrian languages. For example, N1c is common among the Finns, while haplogroup R1a is common among all the neighbours of the Sami.[7]

Haplogroup I1 is the most common haplogroup in Sweden, and the Jokkmokk Sami in Sweden have similar structure to Swedes and Finns for haplogroup I1 and N1c. Haplogroup I-M253 in Sami is explained by immigration (of men) during the 14th century.[8] That is quite late in Sami history bearing in mind that a distinctive Sami culture can be traced and first observed back to 1000 BC.[9]

The Sami languages are thought to have split from their common ancestor about 3300 years ago.[10]

mtDNA

Classification of the Sami mtDNA lineages revealed that the majority are clustered in a subset of the European mtDNA pool. The two haplogroup V and U5b dominate, between them accounting for about 89% of the total. This gives the Sami regions the highest level of haplogroups V and U5b thus far found. Both haplogroups V and U5b are spread at moderate frequencies across Europe, from Iberia to the Ural Mountains. Haplogroups H, D5 and Z represent most of the remaining averaged total. Overall 98% of the Sami mtDNA pool is encompassed within haplogroups V, U5b, H, Z, and D5. Local frequencies among the Sami vary.[6]

The divergence time for the Sami haplogroup V sequences was estimated by Max Ingman and Ulf Gyllensten at 7600 YBP (years before present), and for U5b1b1 as 5500 YBP amongst Sami and 6600 YBP amongst Sami and Finns. This suggests to them an arrival in the region soon after the retreat of the glacial ice.[11]

Other research on Sami shows that most of them do not belong to the mtDNA Haplogroup I[11] (not to be confused for the aforementioned paternal Haplogroup I-M170) that is shared by many Finnic peoples.

U5b

The great majority of Sami belong to U5b U5b even though a small proportion falls into U4. The percentage of total Sami mtDNA samples tested by K. Tambets and her colleagues (published in 2004) which were U5b ranged from 56.8% in Norwegian Sami to 26.5% in Swedish Sami.[6]

In research made by M. Ingman and U. Gyllensten in 2006 is a slightly different setting shown: Norwegian Sami belongs to U5b as well as U5b1b1 to 56.8%, Finnish Sami with 40.6%, Northern Sami in Sweden to 35.5% and Southern Sami in Sweden within reindeer herding to 23.9% while Southern Sami in Sweden outside of reindeer herding/other occupation belong to U5b to 16.3% and to U5b1b1 to 12%.[12]

Sami U5b falls into subclade U5b1b1. The Sami U5b1b1 [6] sub-clade is present in many different populations, e.g. 3% or higher frequencies in Karelia, Finland, and Northern-Russia.[6] The Sami U5b1 motif is additionally found in very low frequencies for instance in the Caucasus region, however this is explained as recent migration from Europe.[13] However 38% of the Sami U5b1b1 mtDNAs have haplotype so far exclusive to the Sami, containing a transition at np 16148.[6]

Alessandro Achilli and colleagues noted that the Sami and the Berbers share U5b1b, which they estimated at 9,000 years old, and argued that this provides evidence for a radiation of the haplogroup from the Franco-Cantabrian refuge area of southwestern Europe.[14]

M. Engman's and U. Gyllensten's study on mtDNA amongst Sami in Scandinavia also reveals that haplogroup H is 15.2% within the Sami traditional group in the south of Sweden, and 34.8% amongst Southern Sami in Sweden, and as high as 44.6% amongst Southern non-traditional Sami in Sweden, but just 2.6% amongst Northern Sami in Sweden, and 2.9 within the Sami group in Finland and amongst Sami in Norway to 4.7%.[12] That result points in the direction that South Sami in Sweden have been more exposed to and/or intermarried the continental European haplogroup H earlier, and much more frequent, than Sami in the north of Sweden, in Finland and in Norway, which can be explained by Scandinavian/Swedish settlers that migrated into Southern Sami areas in Sweden from areas like Mälardalen.

V

The divergence time for the Sami haplogroup V sequences is estimated by M. Ingman and U. Gyllensten at 7,600 years ago. But there is a difference within the Sami group in Sweden according to their study. North Sami (Sami in the North of Swedish Lapland) belong to haplogroup V with 58.6% and South Sami (Sami in the South of Swedish Lapland) within reindeer herding to 37.0% and South Sami outside reindeer herding/other occupation to 8.7%. That can be compared with Sami in Norway that has a 33.1% belonging to haplogroup V and Sami in Finland to 37.7%. Sami in Finland and South Sami within reeinder herding in Sweden have the same percentage belonging to haplogroup V.[11]

But according to K. Tambets' et al. study is haplogroup V the most frequent haplogroup in the Swedish Sami and is present at significantly lower frequencies in Norwegian and Finnish subpopulations.[6] Note though, that in the study made by K. Tambet's et al. has no differentation between Sami in the north and the south of Sweden been made, which otherwise probably would change the outcome of their study.

Torroni and colleagues have suggested that the spread of haplogroup V in Scandinavia and in eastern Europe is due to its late Pleistocene/early Holocene expansion from a Franco-Cantabrian glacial refugium.[15]

However subsequent studies found that haplogroup V is also significantly present in eastern Europeans. Furthermore, haplogroup V lineages with HVS-I transitions 16153 and 16298 that are frequent in the Sami population are much more widespread in eastern than in western Europe. So haplogroup V might have reached Fennoscandia via central/eastern Europe. Such a scenario is indirectly supported by the absence, among the Sami, of the pre-V mtDNAs that are characteristic of southwestern Europeans and northwestern Africans.[6]

Z

Haplogroup Z is found at low frequency in the Sami and Northern Asian populations but is virtually absent in Europe. Several conserved substitutions group the Sami Z lineages with those from Finland and the Volga-Ural region of Russia. The estimated dating of the lineage at 2700 years suggests a small, relatively recent contribution of people from the Volga-Ural region to the Sami population.[11]

Haplogroup Z is most frequent in Northeastern Asia.[16] It is also present in Siberian populations as well as in the region of Volga-Ural,[6] as just mentioned.

Subhaplogroup Z1 is present in lineages in Western Asia and Northern Europe [6] as well as in the Koryak and Itel'men populations.[16] Interestingly enough, is haplogroup Z is most frequent amongst maritime Koryaks with just a bit over 10%, but is not at all present in reindeer-herding Koryaks.[16]: 12 table 3

The Itel'men and Koryak populations live on the Kamchatka peninsula, the former in the south and the latter in the very north.[16]

Autosomal DNA

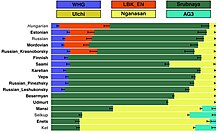

Autosomal genetic analyses have found that the Sámi people cluster in a distinct position, shifted away from other Europeans, with a significant proportion of the genome originating from a Neo-Siberian source population, best represented by the Nganasan people. The specific Siberian-like ancestry is proposed to have arrived in Northeast Europe during the early Iron Age, linked to the arrival of Uralic languages. The Siberian component is estimated to make up roughly 25%. The Mesolithic "Western European Hunter-Gatherer" (WHG) component is close to 15%, while that of the Neolithic "European early farmer" (LBK) is 10%. About 50% is associated with the Bronze Age "Yamna" component, the earliest trace of which is observed in the Pit–Comb Ware culture in Estonia, but in a 2.5-fold lower percentage.[1][18]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b Tambets K, Yunusbayev B, Hudjashov G, Ilumäe AM, Rootsi S, Honkola T, et al. (September 2018). "Genes reveal traces of common recent demographic history for most of the Uralic-speaking populations". Genome Biology. 19 (1): 139. doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1522-1. PMC 6151024. PMID 30241495.

Saami stand out from other NE European populations by drawing up to 30% of their autosomal ancestry from Asian genetic components (Fig. 3). They also display long-range genetic affinities with both the Uralic- and non-Uralic-speaking Siberians (Figs. 4 and 5). We show that (1) the Uralic speakers are genetically most similar to their geographical neighbours; (2) nevertheless, most Uralic speakers along with some of their geographic neighbours share a distinct ancestry component of likely Siberian origin.

- ^ Der Sarkissian C, Balanovsky O, Brandt G, Khartanovich V, Buzhilova A, Koshel S, et al. (2013-02-14). "Ancient DNA reveals prehistoric gene-flow from siberia in the complex human population history of North East Europe". PLOS Genetics. 9 (2): e1003296. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003296. PMC 3573127. PMID 23459685.

- ^ "Ancient DNA shows the Sámi and Finns share identical Siberian genes | University of Helsinki". www.helsinki.fi. 2018-11-27. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Narasimhan VM, Patterson N, Moorjani P, Rohland N, Bernardos R, Mallick S, et al. (September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- ^ Sikora, Martin; Pitulko, Vladimir V.; Sousa, Vitor C.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Vinner, Lasse; Rasmussen, Simon; Margaryan, Ashot; de Barros Damgaard, Peter; de la Fuente, Constanza; Renaud, Gabriel; Yang, Melinda A.; Fu, Qiaomei; Dupanloup, Isabelle; Giampoudakis, Konstantinos; Nogués-Bravo, David (June 2019). "The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene". Nature. 570 (7760): 182–188. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..182S. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1279-z. hdl:1887/3198847. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31168093. S2CID 174809069.

Most modern Siberian speakers of Neosiberian languages genetically fall on an East- West cline between Europeans and Early East Asians. Taking Even speakers as representatives, the Neosiberian turnover from the south, which largely replaced Ancient Paleosiberian ancestry, can be associated with the northward spread of Tungusic and probably also Turkic and Mongolic. However, the expansions of Tungusic as well as Turkic and Mongolic are too recent to be associable with the earliest waves of Neosiberian ancestry, dated later than ~11 kya, but discernible in the Baikal region from at least 6 kya onwards. Therefore, this phase of the Neosiberian population turnover must initially have transmitted other languages or language families into Siberia, including possibly Uralic and Yukaghir.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tambets K, Rootsi S, Kivisild T, Help H, Serk P, Loogväli EL, et al. (April 2004). "The western and eastern roots of the Saami--the story of genetic "outliers" told by mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosomes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (4): 661–682. doi:10.1086/383203. PMC 1181943. PMID 15024688.

- ^ Lappalainen T, Koivumäki S, Salmela E, Huoponen K, Sistonen P, Savontaus ML, Lahermo P (July 2006). "Regional differences among the Finns: a Y-chromosomal perspective". Gene. 376 (2): 207–215. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.004. PMID 16644145.

- ^ Karlsson AO, Wallerström T, Götherström A, Holmlund G (August 2006). "Y-chromosome diversity in Sweden - a long-time perspective". European Journal of Human Genetics. 14 (8): 963–970. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201651. PMID 16724001.

- ^ Hansen LI (2014). Hunters in Transition: An Outline of Early Sámi History. The Northern World. Vol. 63 North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. p. 14. ISBN 978-90-04-25254-7.

- ^ Blažek V. "Uralic Migrations: The Linguistic Evidence" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d Ingman M, Gyllensten U (January 2007). "A recent genetic link between Sami and the Volga-Ural region of Russia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (1): 115–120. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201712. PMID 16985502.

- ^ a b Ingman M, Gyllensten U (January 2007). "A recent genetic link between Sami and the Volga-Ural region of Russia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (1): 115–20. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201712. PMID 16985502. S2CID 21483916.

- ^ Richards M, Macaulay V, Hickey E, Vega E, Sykes B, Guida V, et al. (November 2000). "Tracing European founder lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA pool". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (5): 1251–1276. doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)62954-1. PMC 1288566. PMID 11032788.

- ^ Achilli A, Rengo C, Battaglia V, Pala M, Olivieri A, Fornarino S, et al. (May 2005). "Saami and Berbers--an unexpected mitochondrial DNA link". American Journal of Human Genetics. 76 (5): 883–886. doi:10.1086/430073. PMC 1199377. PMID 15791543.

- ^ Torroni A, Bandelt HJ, Macaulay V, Richards M, Cruciani F, Rengo C, et al. (October 2001). "A signal, from human mtDNA, of postglacial recolonization in Europe". American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (4): 844–852. doi:10.1086/323485. PMC 1226069. PMID 11517423.

- ^ a b c d Schurr TG, Sukernik RI, Starikovskaya YB, Wallace DC (January 1999). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in Koryaks and Itel'men: population replacement in the Okhotsk Sea-Bering Sea region during the Neolithic". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 108 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199901)108:1<1::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 9915299.

- ^ Jeong, Choongwon; Balanovsky, Oleg; Lukianova, Elena; Kahbatkyzy, Nurzhibek; Flegontov, Pavel; Zaporozhchenko, Valery; Immel, Alexander; Wang, Chuan-Chao; Ixan, Olzhas; Khussainova, Elmira; Bekmanov, Bakhytzhan; Zaibert, Victor; Lavryashina, Maria; Pocheshkhova, Elvira; Yusupov, Yuldash (June 2019). "The genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (6): 966–976. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0878-2. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 6542712. PMID 31036896.

- ^ * Lamnidis TC, Majander K, Jeong C, Salmela E, Wessman A, Moiseyev V, et al. (November 2018). "Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe". Nature Communications. 9 (1). Nature Research: 5018. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.5018L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07483-5. PMC 6258758. PMID 30479341.

This model, however, does not fit well for present-day populations from north-eastern Europe such as Saami, Russians, Mordovians, Chuvash, Estonians, Hungarians, and Finns: they carry additional ancestry seen as increased allele sharing with modern East Asian populations1,3,9,10. Additionally, within the Bolshoy population, we observe the derived allele of rs3827760 in the EDAR gene, which is found in near-fixation in East Asian and Native American populations today, but is extremely rare elsewhere37, and has been linked to phenotypes related to tooth shape38 and hair morphology39 (Supplementary Data 2). To further test differential relatedness with Nganasan in European populations and in the ancient individuals in this study, we calculated f4(Mbuti, Nganasan; Lithuanian, Test) (Fig. 3). Consistent with f3-statistics above, all the ancient individuals and modern Finns, Saami, Mordovians and Russians show excess allele sharing with Nganasan when used as Test populations.

"Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe: Fig. 4". Nature Communications. 9. 27 November 2018 – via www.nature.com.

Further reading

- Malmström H, Gilbert MT, Thomas MG, Brandström M, Storå J, Molnar P, et al. (November 2009). "Ancient DNA reveals lack of continuity between neolithic hunter-gatherers and contemporary Scandinavians". Current Biology. 19 (20). Cell Press: 1758–1762. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.017. PMC 4275881. PMID 19781941.

- Mittnik A, Wang CC, Pfrengle S, Daubaras M, Zariņa G, Hallgren F, et al. (January 2018). "The genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region". Nature Communications. 9 (1). Nature Research: 442. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..442M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02825-9. PMC 5789860. PMID 29382937.