Gebel el-Silsila

Gebel el-Silsila جبل السلسلة ẖny Khenu | |

|---|---|

Remains of rock quarries and rock-cut temples along the west bank of the Nile | |

| Coordinates: 24°38′N 32°56′E / 24.633°N 32.933°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aswan Governorate |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EST) |

| Area code | (+20) 97 |

| |

| ||||

| Kheny ẖny in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Kheny ẖny in hieroglyphs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gebel el-Silsila or Gebel Silsileh (Arabic: جبل السلسلة - Jabal al-Silsila or Ǧabal as-Silsila – "Chain of Mountains" or "Series of Mountains"; Egyptian: ẖny, Khenyt,[1] Kheny or Khenu – "The Place of Rowing"; German: Dschabal as-Silsila – "Ruderort", or "Ort des Ruderns" – "Place of Rowing"; Italian: Gebel Silsila – "Monte della Catena" – "Upstream Mountain Chain") is 65 km (40 mi) north of Aswan in Upper Egypt, where the cliffs on both sides close to the narrowest point along the length of the entire Nile. The location is between Edfu[2] in the north towards Lower Egypt and Kom Ombo[2] in the south towards Upper Egypt. The name Kheny (or sometimes Khenu) means "The Place of Rowing". It was used as a major quarry site on both sides of the Nile from at least the 18th Dynasty to Greco-Roman times. Silsila is famous for its New Kingdom stelai and cenotaphs.

Sandstone quarry

During the 18th Dynasty the Egyptians switched from limestone to sandstone. At this time the quarries at Gebelein were not yielding as much limestone as before. Gebel el-Silsila became a source of sandstone.[3] The use of this stone allowed for the use of larger architraves.[3]

Many of the talatats used by Akhenaten were quarried from here and used in buildings at Luxor and Amarna. A stele from the early part of Akhenaten's reign shows the king offering to Amun beneath the winged sun-disk. The inscription records that stone was cut for the great Benben of Harakhty in Thebes.[4] Akhenaten's sculptor Bek oversaw the opening of a stone quarry here.

Shrines, chapels and temples

The site provided numerous stone quarries on both the west and east sides of the Nile. The site contains many shrines erected by officials who would have been in charge of quarrying the stone. Almost all of Ancient Egypt's great temples derived their sandstone from here,[2] such as Karnak,[2] Luxor,[2] Ramesses III's Medinet Habu, Kom Ombo, and the Ramesseum.

Principal deity Sobek

The principal deity of Gebel el-Silsila is Sobek,[5][6] the god of crocodiles and controller of the waters.[2] Silsila is located within the Ancient Egyptian nome of Kom Ombo (or Ombos), Kom Ombo being 15 km (9.3 mi) to the south or upriver. The Roman coins of the Ombite nome exhibit the crocodile and the effigy of the crocodile-headed god Sobek.

West bank subsites

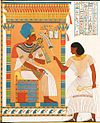

The rock-cut temple of Horemheb is referred to as the Great Speos and may have been created in a former sandstone quarry. The temple is dedicated to seven deities, including Amun, the local god Sobek and Horemheb himself.[3] Later rulers included further scenes and inscriptions to this structure. The scenes on the facade of the Great Speos include Ramesses III offering Maat to Amun-Re, Mut, Khonsu and Sobek in one scene and offering Maat to Anhur-Shu in another scene. Elsewhere Ramesses II is depicted in the company of his Vizier Neferronpet, while offering Maat to Ptah and Sobek. The central doorway contains a stele showing Sety II before Amun-Re, Mut and Khons.[7]

The Great Speos also contains two chapels belonging to Viziers. On the south end of the entrance is the chapel of Panehesy, Vizier to Merenptah. Panehesy is shown adoring Merenptah. Panehesy is also depicted on a stele showing Merenptah, Queen Isetnofret, and Prince Sety-Merenptah (later Seti II).[7] On the northern end is a similar chapel of the Vizier Paser from the reign of Ramesses II. A stele in the doorway shows Ramesses II, Queen Isetnofret and Princess-Queen Bintanath. The king is offering Maat to Ptah and Nefertem.[7]

South of Horemheb's Great Speos are a collection of erected royal stelae. The stelae date to a variety of reigns. They include a rock stela depicting Ramesses V before Amun-Re, Mut, Khons and Sobek.[7] Ramesses III is shown offering Maat to Amun-Re, Mut and Khons.[7] From a much later time is the stele of Shoshenq I. The scene shows Shoshenq accompanied by his son Iuput. The text is dated to year 21 of his reign. The goddess Mut leads the king and his son before Amun-Re, Re-Harakhti and Ptah.[7]

South of the royal stelae several cut shrines are found. These include shrines for the Scribe of the Treasury of Thutmose, the Overseer of the Seal of Min (from the time of Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III), an official named Maa, and the Scribe of the Nome Ahmose (from the time of Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III).[7]

North of the royal stelae more shrines can be found. One shrine belonged to an official dated to the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III: User, vizier. A shrine at this site records User's family, including his father Amethu called Ahmose.[7][8]

Further shrines were constructed near the river. Most of these date to the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III. Included are the shrines of some high-ranking officials such as the Overseer of the Granaries Minnakht, the Overseer of the Seal and Royal Herald Sennufer, the Overseer of the Seal Nehesy, the Overseer of the Prophets of Upper and Lower Egypt Hapuseneb, and the Great Steward of the Queen Senenmut.[7] Senenmut's is noteworthy because the inscriptions show a change in the status of Hatshepsut. She is said to be the "King's First-born Daughter" and she is depicted as a pharaoh in a striding fashion.[8]

Additionally, three rock-cut shrines were constructed and the site also shows some royal stelae. The shrines belong to Seti I, Ramesses II and Merenptah.[3][7] One of the stele depicts Ramesses III offering wine to Amun-Re, Re-Harakhty and Hapi. The stele mentions year 6 of the reign of Ramesses III. Adjoining this is another stele, this one depicting Horemheb adoring Sety I.[7]

Between the shrines of Merenptah and Ramesses II a stele was erected depicting Merenptah and a son (likely Sety-Merenptah, but the name has been destroyed) offering Maat to Amun-Re. The royals are accompanied by the Vizier Panehesy.[7]

East bank subsites

Survey work of the east bank has revealed 49 quarries, the largest being Quarry 34 (Q34) (reviewed in 7 partitions due to its immensity) containing 54 stone huts.

The East bank holds several stele from the time of Amenhotep III. The stele and their texts are described in Karl Richard Lepsius' Denkmahler. The stelae are damaged, but one of them was inscribed in year 35. Amenhotep is shown adoring Amun-Re and is called "beloved of Sobek" in the inscriptions.[9] The stela have been studied and described by Georges Legrain.[7]

A shrine with stele on three sides depicting Amenhotep III is located at Gebel el-Silisila East.[9] In the scenes Amenhotep III is accompanied by an official named Amenhotep, who held the title "Eyes of the King in the whole land".[7]

A stela was discovered showing Akhenaten—named Amenhotep IV—before Amun-Re.[7]

Further finds date to the time of Sety I. An inscription from year 6 shows Sety I before Amun-Re, Ptah and a goddess. Another stele shows the Commander of troops of the fortress of the Lord of the Two Lands, named Hapi adoring the cartouche of Sety I.[7]

The rediscovery of the Temple of Kheny[2] is a significant find for the east bank.[5] The other item of significance is the collection of over 5,000 epigraphic symbols and hieroglyphs collected from this site and all over Egypt.[5] There appears to be an image depicting the actual transport of the sandstone blocks to temple sites.[5]

The east bank also has two unfinished ram-headed sphinxes or criosphinxes.

Indications have been noted of possible stables providing horses to the Roman Caesars.[5]

Table of monuments

This is a list of notable monuments for Gebel el-Silsila.

| MONUMENTS AT GEBEL el-SILSILA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monument Name | Alternate Name | Bank (West/East) |

Type | Characteristic | Stone | Dedicated to | Features | Notes |

| West Bank | ||||||||

| Temple of Horemheb | The Great Speos | West | Temple | Rock-cut | Sandstone | 7 deities, including Amun, the local god Sobek, and Horemheb | Facade scene includes Ramesses III offering Maat to Amun-Re, Mut, Khonsu, and Sobek; another scene offers Maat to Anhur-Shu. | Largest structure at Silsila. |

| Chapel of Panehesy | Speos south chapel | West | Chapel within temple | Sandstone | ||||

| Chapel of Paser | Speos north chapel | West | Chapel within temple | Sandstone | ||||

| East Bank | ||||||||

| Temple of Kheny | East | Temple | Limestone early; Sandstone later | Local god Sobek | Remnants. 4 floors. | |||

Temple of Kheny (Temple of Sobek)

Remains of the Temple of Kheny have been rediscovered[2] as surface remnants at Gebel el Silsila,[2][5] showing the temple foundations and blockwork.[2] The ruins are one of the few remnants of the settlement of Kheny or Khenu, the ancient Egyptian name, meaning "Rowing Place", for Gebel el-Silsila.[2] The finding confirms that Gebel el Silsila is a sacred site in addition to its quarry function.[2] It is unknown at this time to whom the temple is dedicated,[2] but there are indications that it may be to Sobek.[5] Further, the site seems to lean towards solar worship.[5]

The worship center was described as a destroyed Ramesside[2] temple on a 1934 published rudimentary map by Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt[2] after being recorded between 1906 and 1925.[2] The temple was then forgotten and lost.[2]

The temple appears to have four "dressed floor levels".[2] Two painted sandstone fragments indicate that the temple's ceiling had an astronomical motif with stars and sky representing the celestial heavens.[2]

The rediscovery and on-site work have been conducted since 2012 by teams led by archeologists Maria Nilsson[2] and John Ward[2] as part of the Gebel el Silsila Survey Project.[2]

Possible official change from limestone to sandstone in Ancient Egypt

The changeover of constructing temples in Ancient Egypt from limestone to sandstone may have started with the Temple of Kheny.[2][5] It appears that the Temple of Kheny may be the "mother temple" to all future temples built with sandstone.[5]

According to Nilsson:[2]

The oldest building phase of the temple was made up by limestone, which is unique within a sandstone quarry, and may signify the official changeover from limestone construction to sandstone.

Gebel el Silsila Epigraphic Survey Project

The entire site of Gebel el Silsila covering about 20 square kilometers is in a multi-year epigraphic survey project directed by archaeologist Maria Nilsson[2] under the auspices of Lund University,[2] and assistant-director John Ward. As of 2015, the team had 13 members, 2 SCA inspectors, and assistants.[2][11] Various teams organized by them have been working on-site since 2012. Emphasis has been placed on the east bank due to insufficient recording in the past and deteriorating conditions in the present epigraphically. Its major finding is the Temple of Kheny. The project is also noted for its use of digital archaeology.

The survey project has also found a blue scarab, an amulet depiction of a dung beetle.

Recent discoveries

In February in 2019, joint Swedish-Egyptian archaeologists revealed a 16.4-feet longs and 11.5-feet high ram-headed sphinx (or a criosphinx) carved from sandstone dated back to the reign of Amenhotep III. In addition to this finding, an "uraeus" or wrapped cobra symbol and hundreds of stone fragment engraved with hieroglyphs were also found.[12][13][14]

Climate

The present-day climate of Gebel el-Silsila (Khenu) is extremely clear, dry, bright, and sunny year-round, in all seasons, with low seasonal variation, and with about 4,000 hours of annual sunshine, very close to the maximum theoretical sunshine duration. Silsila is located in one of the sunniest regions on Earth.

The Köppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies the weather of Gebel el-Silsila as a hot desert climate (BWh), like the rest of Egypt.

Winters are short, brief, and extremely warm. Wintertime is very pleasant and enjoyable while summertime is unbearably hot with blazing sunshine, made only more bearable because the desert air is dry.

The climate of Khenu is extremely dry year-round, with less than 1 mm of average annual precipitation. The desert locale is one of the driest ones in the world, and rainfall does not occur every year. The air is mainly dry here and becomes drier southward and upriver towards Aswan. The air becomes more humid northward and downriver towards Luxor.

24°38′N 32°56′E / 24.633°N 32.933°E

See also

- Regarding quarrying

- Regarding Sobek or religion

- Other

- Cultural tourism in Egypt

- List of ancient Egyptian sites

- List of megalithic sites

- Outline of ancient Egypt

- Glossary of ancient Egypt artifacts

- Index of ancient Egypt-related articles

References

- Citations

- ^ Kitchen (1983).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa DNews (2015).

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson (2000), pp. 40, 65, 208.

- ^ Tyldesley (1998), p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Intrepid radio interview (2015).

- ^ Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, 218–220

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Porter & Moss (1937, 2004), vol. 5.

- ^ a b O'Connor & Cline (2006), pp. 48, 74.

- ^ a b c d e Lepsius (1849).

- ^ Lepsius (1849), Vol. 4 (Texts) (Upper Egypt), p. 97.

- ^ "Gebel el Silsila Survey Project". Gebel el Silsila Survey Project. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ February 2019, Stephanie Pappas 27. "Ram-Headed Sphinx Abandoned by King Tut's Grandfather Found in Egypt". livescience.com. Retrieved 2020-09-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Crio sphinx linked to King Tut's grandfather discovered". EgyptToday. Retrieved 2020-09-13.

- ^ Rogers, James (2019-03-01). "Amazing ram-headed sphinx linked to King Tut's grandfather discovered in Egypt". Fox News. Retrieved 2020-09-13.

Books

- English

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1983). Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt, Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0856682155.

- O'Connor, David and Cline, Eric H. (2006). Thutmose III: A New Biography. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472114672.

- Nilsson, Maria; Almásy-Martin, Adrienn; Ward, John (2023). Greek inscriptions on the East Bank. Leiden Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004540682.

- Porter, Bertha; and Moss, Rosalind (1937). Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings, V Upper Egypt: Sites (Volume 5). Griffith Institute. 1937, 1962; 2004: ISBN 978-0900416835.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (1998). Nefertiti: Egypt's Sun Queen. Penguin. ISBN 0-670-86998-8.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt, Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05100-3.

- German

- Lepsius, Karl Richard (1849). [Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia]. Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien nach den Zeichnungen der von Seiner Majestät dem Koenige von Preussen, Friedrich Wilhelm IV., nach diesen Ländern gesendeten, und in den Jahren 1842–1845 ausgeführten wissenschaftlichen Expedition auf Befehl Seiner Majestät. 13 vols. Berlin: Nicolaische Buchhandlung. (Reprinted Genève: Éditions de Belles-Lettres, 1972). Retrieved online Lepsius Denkmahler.

Audio/radio

- Interview by Scott Roberts of Maria Nilsson and John Ward (while both in Sweden), The Intrepid Radio Program broadcast, Intrepid Paradigm Broadcast Network, 2015 May 31 Sunday 9-11 p.m. CDT (2015 June 1 UTC 0400-0600 UTC), Wisconsin, U.S.A., archived podcast 2015 June 1; accessed 2011 June 11.

Web

- "Long-Lost Egyptian Temple Found". DNews (Discovery News). Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

External links

- Friends of Silsila Archived 2021-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Gebel el Silsila (Epigraphic) Survey Project blog

- Photo gallery of "Gebel el Silsileh: The Quarries East and West", part of "The Egyptian Theben Desert Portfolio" by Yarko Kobylecky