Gauls

The Gauls (Latin: Galli; Ancient Greek: Γαλάται, Galátai) were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (Gallia). They spoke Gaulish, a continental Celtic language.

The Gauls emerged around the 5th century BC as bearers of La Tène culture north and west of the Alps. By the 4th century BC, they were spread over much of what is now France, Belgium,[1] Switzerland, Southern Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic,[1] by virtue of controlling the trade routes along the river systems of the Rhône, Seine, Rhine, and Danube. They reached the peak of their power in the 3rd century BC. During the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, the Gauls expanded into Northern Italy (Cisalpine Gaul), leading to the Roman–Gallic wars, and into the Balkans, leading to war with the Greeks. These latter Gauls eventually settled in Anatolia (contemporary Turkey), becoming known as Galatians.[1]

After the end of the First Punic War, the rising Roman Republic increasingly put pressure on the Gallic sphere of influence. The Battle of Telamon (225 BC) heralded a gradual decline of Gallic power during the 2nd century BC. The Romans eventually conquered Gaul in the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), making it a Roman province, which brought about the hybrid Gallo-Roman culture.

The Gauls were made up of many tribes (toutās), many of whom built large fortified settlements called oppida (such as Bibracte), and minted their own coins. Gaul was never united under a single ruler or government, but the Gallic tribes were capable of uniting their armies in large-scale military operations, such as those led by Brennus and Vercingetorix. They followed an ancient Celtic religion overseen by druids. The Gauls produced the Coligny calendar.

Name

The ethnonym Galli is generally derived from a Celtic root *gal- 'power, ability' (cf. Old Breton gal 'power, ability', Irish gal 'bravery, courage').[2][3] Brittonic reflexes give evidence of an n-stem *gal-n-, with the regular development *galn- > gall- (cf. Middle Welsh gallu, Middle Breton gallout 'to be able', Cornish gallos 'power').[3] The ethnic names Galátai and Gallitae, as well as Gaulish personal names such as Gallus or Gallius, are also related.[3] The modern French gaillard ('brave, vigorous, healthy') stems from the Gallo-Latin noun *galia- or *gallia- ('power, strength').[2][3] Linguist Václav Blažek has argued that Irish gall ('foreigner') and Welsh gâl ('enemy, hostile') may be later adaptations of the ethnic name Galli that were introduced to the British Isles during the 1st millennium AD.[2]

According to Caesar (mid-1st c. BC), the Gauls of the province of Gallia Celtica called themselves Celtae in their own language, and were called Galli in Latin.[4] Romans indeed used the ethnic name Galli as a synonym for Celtae.[2]

The English Gaul does not come from Latin Galli but from Germanic *Walhaz, a term stemming from the Gallic ethnonym Volcae that came to designate more generally Celtic and Romance speakers in medieval Germanic languages (e.g. Welsh, Waals, Vlachs).[5]

History

Origins and early history

Gaulish culture developed over the first millennium BC. The Urnfield culture (c. 1300–750 BC) represents the Celts as a distinct cultural branch of the Indo-European-speaking people.[6] The spread of iron working led to the Hallstatt culture in the 8th century BC; the Proto-Celtic language is often thought to have been spoken around this time. The Hallstatt culture evolved into La Tène culture in around the 5th century BC. The Greek and Etruscan civilizations and colonies began to influence the Gauls, especially in the Mediterranean area. Gauls under Brennus invaded Rome circa 390 BC.

By the 5th century BC, the tribes later called Gauls had migrated from Central France to the Mediterranean coast.[7] Gallic invaders settled the Po Valley in the 4th century BC, defeated Roman forces in a battle under Brennus in 390 BC, and raided Italy as far south as Sicily.[1]

In the early 3rd century BC, the Gauls attempted an eastward expansion, toward the Balkan peninsula. At that time, it was a Greek province. The Gauls' intent was to reach and loot the rich Greek city-states of the Greek mainland. However, the Greeks exterminated the majority of the Gallic army, and the few survivors were forced to flee.

Many Gauls were recorded as serving in the armies of Carthage during the Punic Wars. One of the leading rebel leaders of the Mercenary War, Autaritus, was of Gallic origin.

Balkan wars

During the Balkan expedition, led by Cerethrios, Brennos and Bolgios, the Gauls raided the Greek mainland twice.

At the end of the second expedition, the Gallic raiders had been repelled by the coalition armies of the various Greek city-states and were forced to retreat to Illyria and Thrace, but the Greeks were forced to grant safe passage to the Gauls who then made their way to Asia Minor and settled in Central Anatolia. The Gallic area of settlement in Asia Minor was called Galatia; there they created widespread havoc. They were checked through the use of war elephants and skirmishers by the Greek Seleucid king Antiochus I in 275 BC, after which they served as mercenaries across the whole Hellenistic Eastern Mediterranean, including Ptolemaic Egypt, where they, under Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC), attempted to seize control of the kingdom.[8]

In the first Gallic invasion of Greece (279 BC), they defeated the Macedonians and killed the Macedonian king Ptolemy Keraunos. They then focused on looting the rich Macedonian countryside, but avoided the heavily fortified cities. The Macedonian general Sosthenes assembled an army, defeated Bolgius and repelled the invading Gauls.

In the second Gaulish invasion of Greece (278 BC), the Gauls, led by Brennos, suffered heavy losses while facing the Greek coalition army at Thermopylae, but helped by the Heracleans they followed the mountain path around Thermopylae to encircle the Greek army in the same way that the Persian army had done at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC, but this time defeating the whole of the Greek army.[9] After passing Thermopylae, the Gauls headed for the rich treasury at Delphi, where they were defeated by the re-assembled Greek army. This led to a series of retreats of the Gauls, with devastating losses, all the way up to Macedonia and then out of the Greek mainland. The major part of the Gaul army was defeated in the process, and those Gauls survived were forced to flee from Greece. The Gallic leader Brennos was seriously injured at Delphi and committed suicide there. (He is not to be confused with another Gaulish leader bearing the same name who had sacked Rome a century earlier (390 BC).

Galatian war

In 278 BC, Gaulish settlers in the Balkans were invited by Nicomedes I of Bithynia to help him in a dynastic struggle against his brother. They numbered about 10,000 fighting men and about the same number of women and children, divided into three tribes, Trocmi, Tolistobogii and Tectosages. They were eventually defeated by the Seleucid king Antiochus I (275 BC), in a battle in which the Seleucid war elephants shocked the Galatians. Although the momentum of the invasion was broken, the Galatians were by no means exterminated, and continued to demand tribute from the Hellenistic states of Anatolia to avoid war. Four thousand Galatians were hired as mercenaries by the Ptolemaic Egyptian king Ptolemy II Philadelphus in 270 BC. According to Pausanias, soon after arrival the Celts plotted “to seize Egypt”, and so Ptolemy marooned them on a deserted island in the Nile River.[8]

Galatians also participated at the victory at Raphia in 217 BC under Ptolemy IV Philopator, and continued to serve as mercenaries for the Ptolemaic dynasty until its demise in 30 BC. They sided with the renegade Seleucid prince Antiochus Hierax, who reigned in Asia Minor. Hierax tried to defeat king Attalus I of Pergamum (241–197 BC), but instead, the Hellenized cities united under Attalus's banner, and his armies inflicted a severe defeat upon the Galatians at the Battle of the Caecus River in 241 BC. After this defeat, the Galatians continued to be a serious threat to the states of Asia Minor. In fact, they continued to be a threat even after their defeat by Gnaeus Manlius Vulso in the Galatian War (189 BC). Galatia declined and at times fell under Pontic ascendancy. They were finally freed by the Mithridatic Wars, in which they supported Rome. In the settlement of 64 BC, Galatia became a client state of the Roman empire, the old constitution disappeared, and three chiefs (wrongly styled "tetrarchs") were appointed, one for each tribe. But this arrangement soon gave way before the ambition of one of these tetrarchs, Deiotarus, a contemporary of Cicero and Julius Caesar, who made himself master of the other two tetrarchies and was finally recognized by the Romans as 'king' of Galatia. The Galatian language continued to be spoken in central Anatolia until the 6th century.[10]

Roman wars

In the Second Punic War, the famous Carthaginian general Hannibal used Gallic mercenaries in his invasion of Italy. They played a part in some of his most spectacular victories, including the battle of Cannae. The Gauls were so prosperous by the 2nd century that the powerful Greek colony of Massilia had to appeal to the Roman Republic for defense against them. The Romans intervened in southern Gaul in 125 BC, and conquered the area eventually known as Gallia Narbonensis by 121 BC.

In 58 BC, Julius Caesar launched the Gallic Wars and had conquered the whole of Gaul by 51 BC. He noted that the Gauls (Celtae) were one of the three primary peoples in the area, along with the Aquitanians and the Belgae. Caesar's motivation for the invasion seems to have been his need for gold to pay off his debts and for a successful military expedition to boost his political career. The people of Gaul could provide him with both. So much gold was looted from Gaul that after the war the price of gold fell by as much as 20%. While they were militarily just as brave as the Romans, the internal division between the Gallic tribes guaranteed an easy victory for Caesar, and Vercingetorix's attempt to unite the Gauls against Roman invasion came too late.[11][12] After the annexation of Gaul, a mixed Gallo-Roman culture began to emerge.

Roman Gaul

After more than a century of warfare, the Cisalpine Gauls were subdued by the Romans in the early 2nd century BC. The Transalpine Gauls continued to thrive for another century, and joined the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones in the Cimbrian War, where they defeated and killed a Roman consul at Burdigala in 107 BC, and later became prominent among the rebelling gladiators in the Third Servile War.[13] The Gauls were finally conquered by Julius Caesar in the 50s BC despite a rebellion by the Arvernian chieftain Vercingetorix. During the Roman period the Gauls became assimilated into Gallo-Roman culture and by expanding Germanic tribes. During the crisis of the third century, there was briefly a breakaway Gallic Empire founded by the Batavian general Postumus.

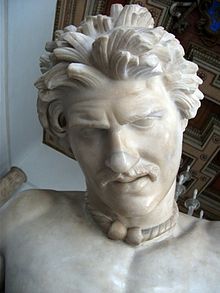

Physical appearance

First-century BC Roman poet Virgil wrote that the Gauls were light-haired, and golden their garb:

Golden is their hair and golden their garb. They are resplendant in their striped cloaks and their milk white necks are circled in gold.[14]

First-century BC Greek historian Diodorus Siculus described them as tall, generally heavily built, very light-skinned, and light-haired, with long hair and mustaches:

The Gauls are tall of body, with rippling muscles, and white of skin, and their hair is blond, and not only naturally so, but they make it their practice to increase the distinguishing color by which nature has given it. For they are always washing their hair in limewater, and they pull it back from their forehead to the top of the head and back to the nape of the neck... Some of them shave their beards, but others let it grow a little; and the nobles shave their cheeks, but they let the mustache grow until it covers the mouth.[15]

Jordanes, in his Origins and Deeds of the Goths, indirectly describes the Gauls as light-haired and large-bodied by comparing them to Caledonians, as a contrast to the Spaniards, whom he compared to the Silures. He speculates based on this comparison that the Britons originated from different peoples, including Gauls and Spaniards.

The Silures have swarthy features and are usually born with curly black hair, but the inhabitants of Caledonia have reddish hair and large loose-jointed bodies. They [the Britons] are like the Gauls and the Spaniards, according as they are opposite either nation. Hence some have supposed that from these lands the island received its inhabitants.

Tacitus noted the Caledonians had "red hair and large limbs" which he felt pointed to a "Germanic origin."

In the novel Satyricon by Roman courtier Gaius Petronius, a Roman character sarcastically suggests that he and his partner "chalk our faces so that Gaul may claim us as her own" in the midst of a rant outlining the problems with his partner's plan of using blackface to impersonate Aethiopians. This suggests that Gauls were thought of on average to be much paler than Romans.[16] Jordanes describes the physical attributes of the Gauls as including "reddish hair and large loose-jointed bodies."[17]

Culture

All over Gaul, archeology has uncovered many pre-Roman gold mines (at least 200 in the Pyrenees), suggesting they were very rich, also evidenced by large finds of gold coins and artifacts. Also there existed highly developed population centers, called oppida by Caesar, such as Bibracte, Gergovia, Avaricum, Alesia, Bibrax, Manching and others. Modern archeology strongly suggests that the countries of Gaul were quite civilized and very wealthy. Most had contact with Roman merchants and some, particularly those that were governed by Republics such as the Aedui, Helvetii and others, had enjoyed stable political alliances with Rome. They imported Mediterranean wine on an industrial scale, evidenced by large finds of wine vessels in digs all over Gaul, the largest and most famous of which being the one discovered in Vix Grave, which stands 1.63 m (5′ 4″) high.[citation needed]

Art

Gallic art corresponds to two archaeological material cultures: the Hallstatt culture (c. 1200–450 BC) and the La Tène culture (c. 450–1 BC). Each of these eras has a characteristic style, and while there is much overlap between them, the two styles recognizably differ. From the late Hallstatt onwards and certainly through the entirety of La Tène, Gaulish art is reckoned to be the beginning of what is called Celtic art today.[17] After the end of the La Tène and from the beginning of Roman rule, Gaulish art evolved into Gallo-Roman art.

Hallstatt decoration is mostly geometric and linear, and is best seen on fine metalwork finds from graves. Animals, with waterfowl a particular favorite, are often included as part of ornamentation, more often than humans. Commonly found objects include weapons, in latter periods often with hilts terminating in curving forks ("antenna hilts"),[18] and jewelry, which include fibulae, often with a row of disks hanging down on chains, armlets, and some torcs. Though these are most often found in bronze, some examples, likely belonging to chieftains or other preeminent figures, are made of gold. Decorated situlae and bronze belt plates show influence from Greek and Etruscan figurative traditions. Many of these characteristics were continued into the succeeding La Tène style.[19]

La Tène metalwork in bronze, iron and gold, developing technologically out of the Hallstatt culture, is stylistically characterized by "classical vegetable and foliage motifs such as leafy palmette forms, vines, tendrils and lotus flowers together with spirals, S-scrolls, lyre and trumpet shapes".[20] Such decoration may be found on fine bronze vessels, helmets and shields, horse trappings, and elite jewelry, especially torcs and fibulae. Early on, La Tène style adapted ornamental motifs from foreign cultures into something distinctly new; the complicated brew of influences include Scythian art as well as that of the Greeks and Etruscans, among others. The Achaemenid occupation of Thrace and Macedonia around 500 BC is a factor of uncertain importance.[21]

- A belt made of 2.8 kilograms (6.2 lb) of pure gold, discovered in Guînes, France, 1200–1000 BC

- Celtic gold bracelet found in Cantal, France

- Celtic helmet decorated with gold "triskeles", found in Amfreville-sous-les-Monts, France, 400 BC

- Gaul, Curiosolites coin showing stylized head and horse (c. 100–50 BC)

- Gaul, Armorica coin showing stylized head and horse (Jersey moon head style, c. 100–50 BC)

Social structure

Gaulish society was dominated by the druid priestly class.[citation needed] The druids were not the only political force, however, and the early political system was complex. The fundamental unit of Gallic politics was the tribe, which itself consisted of one or more of what Caesar called "pagi".[citation needed] Each tribe had a council of elders, and initially a king. Later, the executive was an annually-elected magistrate.[citation needed] Among the Aedui tribe the executive held the title of "Vergobret", a position much like a king, but its powers were held in check by rules laid down by the council.[citation needed]

The tribal groups, or pagi as the Romans called them (singular: pagus; the French word pays, "country", comes from this term) were organized into larger super-tribal groups that the Romans called civitates. These administrative groupings would be taken over by the Romans in their system of local control, and these civitates would also be the basis of France's eventual division into ecclesiastical bishoprics and dioceses, which would remain in place—with slight changes—until the French Revolution imposed the modern departmental system.

Though the tribes were moderately stable political entities, Gaul as a whole tended to be politically divided, there being virtually no unity among the various tribes.[citation needed] Only during particularly trying times, such as the invasion of Caesar, could the Gauls unite under a single leader like Vercingetorix. Even then, however, the faction lines were clear.[citation needed]

The Romans divided Gaul broadly into Provincia (the conquered area around the Mediterranean), and the northern Gallia Comata ("free Gaul" or "wooded Gaul"). Caesar divided the people of Gaulia Comata into three broad groups: the Aquitani; Galli (who in their own language were called Celtae); and Belgae. In the modern sense, Gallic tribes are defined linguistically, as speakers of Gaulish. While the Aquitani were probably Vascons, the Belgae would thus probably be counted among the Gauls tribes, perhaps with Germanic elements.[citation needed]

Julius Caesar, in his book, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, comments:

All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, whereas those who in their own language are called Celts and in ours Gauls, the third.

All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws.

The river Garonne separates the Gauls from the Aquitani; the rivers Marne and Seine separate them from the Belgae.

Of all these, the Belgae are the bravest, because they are furthest from the civilisation and refinement of (our) Province, and merchants least frequently resort to them, and import those things which tend to effeminate the mind; and they are the nearest to the Germani, who dwell beyond the Rhine, with whom they are continually waging war; for which reason the Helvetii also surpass the rest of the Gauls in valour, as they contend with the Germani in almost daily battles, when they either repel them from their own territories, or themselves wage war on their frontiers. One part of these, which it has been said that the Gauls occupy, takes its beginning at the river Rhône; it is bounded by the river Garonne, the Atlantic Ocean, and the territories of the Belgae; it borders, too, on the side of the Sequani and the Helvetii, upon the river Rhine, and stretches toward the north.

The Belgae rises from the extreme frontier of Gaul, extend to the lower part of the river Rhine; and look toward the north and the rising sun.

Aquitania extends from the Garonne to the Pyrenees and to that part of the Atlantic (Bay of Biscay) which is near Spain: it looks between the setting of the sun, and the north star.

Language

Gaulish or Gallic is the name given to the Celtic language spoken in Gaul before Latin took over. According to Caesar's Commentaries on the Gallic War, it was one of three languages in Gaul, the others being Aquitanian and Belgic.[22] In Gallia Transalpina, a Roman province by the time of Caesar, Latin was the language spoken since at least the previous century. Gaulish is paraphyletically grouped with Celtiberian, Lepontic, and Galatian as Continental Celtic. Lepontic and Galatian are sometimes considered dialects of Gaulish.

The exact time of the final extinction of Gaulish is unknown, but it is estimated to be around or shortly after the middle of the 1st millennium.[23] Gaulish may have survived in some regions as the mid to late 6th century in France.[24] Despite considerable Romanization of the local material culture, the Gaulish language is held to have survived and had coexisted with spoken Latin during the centuries of Roman rule of Gaul.[24] Coexisting with Latin, Gaulish played a role in shaping the Vulgar Latin dialects that developed into French, with effects including loanwords and calques,[25][26] sound changes shaped by Gaulish influence,[27][28] as well as in conjugation and word order.[25][26][29] Recent work in computational simulation suggests that Gaulish played a role in gender shifts of words in Early French, whereby the gender would shift to match the gender of the corresponding Gaulish word with the same meaning.[30]

Religion

Like other Celtic peoples, the Gauls had a polytheistic religion.[31] Evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology and Greco-Roman accounts.[32]

Some deities were venerated only in one region, but others were more widely known.[31] The Gauls seem to have had a father god, who was often a god of the tribe and of the dead (Toutatis probably being one name for him); and a mother goddess who was associated with the land, earth and fertility[33] (Matrona probably being one name for her). The mother goddess could also take the form of a war goddess as protectress of her tribe and its land.[33] There also seems to have been a male celestial god—identified with Taranis—associated with thunder, the wheel, and the bull.[33] There were gods of skill and craft, such as the pan-regional god Lugus, and the smith god Gobannos.[33] Gallic healing deities were often associated with sacred springs,[33] such as Sirona and Borvo. Other pan-regional deities include the horned god Cernunnos, the horse and fertility goddess Epona, Ogmios, Sucellos[31][32] and his companion Nantosuelta. Caesar says the Gauls believed they all descended from a god of the dead and underworld, whom he likened to Dīs Pater.[31] Some deities were seen as threefold,[34] like the Three Mothers.[35] According to Miranda Aldhouse-Green, the Celts were also animists, believing that every part of the natural world had a spirit.[32]

Greco-Roman writers say the Gauls believed in reincarnation. Diodorus says they believed souls were reincarnated after a certain number of years, probably after spending time in an afterlife, and noted they buried grave goods with the dead.[36]

Gallic religious ceremonies were overseen by priests known as druids, who also served as judges, teachers, and lore-keepers.[37] There is evidence that the Gauls sacrificed animals, almost always livestock. An example is the sanctuary at Gournay-sur-Aronde. It appears some were offered wholly to the gods (by burying or burning), while some were shared between gods and humans (part eaten and part offered).[38] There is also some evidence that the Gauls sacrificed humans, and some Greco-Roman sources claim the Gauls sacrificed criminals by burning them in a wicker man.[39]

The Romans said the Gauls held ceremonies in sacred groves and other natural shrines, called nemetons.[31] Celtic peoples often made votive offerings: treasured items deposited in water and wetlands, or in ritual shafts and wells, often in the same place over generations.[31]

Among the Romans and Greeks, the Gauls had a reputation as head hunters. There is archaeological evidence of a "head cult" among the Gallic Salyes, who embalmed and displayed severed heads, for example at Entremont.[40][41]

The Roman conquest gave rise to a syncretic Gallo-Roman religion, with deities such as Lenus Mars, Apollo Grannus, and the pairing of Rosmerta with Mercury.

List of Gaulish tribes

The Gauls were made up of many tribes who controlled a particular territory and often built large fortified settlements called oppida. After completing the conquest of Gaul, the Roman Empire made most of these tribes civitates. The geographical subdivisions of the early church in Gaul were then based on these, and continued as French dioceses until the French Revolution.

The following is a list of recorded Gaulish tribes, in both Latin and the reconstructed Gaulish language (*), as well as their capitals during the Roman period.

Modern reception

The Gauls played a certain role in the national historiography and national identity of modern France. Attention given to the Gauls as the founding population of the French nation was traditionally second to that enjoyed by the Franks, out of whose kingdom the historical kingdom of France arose under the Capetian dynasty; for example, Charles de Gaulle is on record as stating, "For me, the history of France begins with Clovis, elected as king of France by the tribe of the Franks, who gave their name to France. Before Clovis, we have Gallo-Roman and Gaulish prehistory. The decisive element, for me, is that Clovis was the first king to have been baptized a Christian. My country is a Christian country and I reckon the history of France beginning with the accession of a Christian king who bore the name of the Franks."[43]

However, the dismissal of "Gaulish prehistory" as irrelevant for French national identity has been far from universal. Pre-Roman Gaul has been evoked as a template for French independence especially during the Third French Republic (1870–1940). An iconic phrase summarizing this view is that of "our ancestors the Gauls" (nos ancêtres les Gaulois), associated with the history textbook for schools by Ernest Lavisse (1842–1922), who taught that "the Romans established themselves in small numbers; the Franks were not numerous either, Clovis having but a few thousand men with him. The basis of our population has thus remained Gaulish. The Gauls are our ancestors."[44]

Astérix, the popular series of French comic books following the exploits of a village of "indomitable Gauls", satirizes this view by combining scenes set in classical antiquity with modern ethnic clichés of the French and other nations.

Similarly, in Swiss national historiography of the 19th century, the Gaulish Helvetii were chosen as representing the ancestral Swiss population (compare Helvetia as national allegory), as the Helvetii had settled in both the French and the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, and their Gaulish language set them apart from Latin- and German-speaking populations in equal measure.

Genetics

A genetic study published in PLOS One in December 2018 examined 45 individuals buried at a La Téne necropolis in Urville-Nacqueville, France.[45] The people buried there were identified as Gauls.[45] The mtDNA of the examined individuals belonged primarily to haplotypes of H and U.[45] They were found to be carrying a large amount of steppe ancestry (originating near what is now Ukraine and southwestern Russia), and to have been closely related to peoples of the preceding Bell Beaker culture, suggesting genetic continuity between Bronze Age and Iron Age France. Significant gene flow with Great Britain and Iberia was detected. The results of the study partially supported the belief that French people are largely descended from the Gauls.[45]

A genetic study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science in October 2019 examined 43 maternal and 17 paternal lineages for the La Téne necropolis in Urville-Nacqueville, France, and 27 maternal and 19 paternal lineages for La Téne tumulus of Gurgy ‘Les Noisats’ near modern Paris, France.[46] The examined individuals displayed strong genetic resemblance to peoples of the earlier Yamnaya culture, Corded Ware culture and Bell Beaker culture.[46] They carried a diverse set of maternal lineages associated with steppe ancestry.[46] The paternal lineages were on the other hand belonged entirely to haplogroup R and R1b, both of whom are associated with steppe ancestry.[46] The evidence suggested that the Gauls of the La Téne culture were patrilineal and patrilocal, which is in agreement with archaeological and literary evidence.[46]

A genetic study published in iScience in April 2022 examined 49 genomes from 27 sites in Bronze Age and Iron Age France. The study found evidence of strong genetic continuity between the two periods, particularly in southern France. The samples from northern and southern France were highly homogenous, with northern samples displaying links to contemporary samples form Great Britain and Sweden, and southern samples displaying links to Celtiberians. The northern French samples were distinguished from the southern ones by elevated levels of steppe-related ancestry. R1b was by far the most dominant paternal lineage, while H was the most common maternal lineage. The Iron Age samples resembled those of modern-day populations of France, Great Britain and Spain. The evidence suggested that the Gauls of the La Téne culture largely evolved from local Bronze Age populations.[47]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d "Gaul (ancient region, Europe)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d Blažek 2008, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Matasović 2009, p. 150.

- ^ Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres, quarum unam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquitani, tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur. Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Book I, chapter 1

- ^ "Gaul definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary".

- ^ Pinault, Georges-Jean (2007). Gaulois et celtique continental (in French). Librairie Droz. p. 381. ISBN 9782600013376.

- ^ "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 5, chapter 34". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ^ a b Hinds, Kathryn (2009). Ancient Celts. Marshall Cavendish. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4165-3205-7.

- ^ Scholten, Joseph Bernard (1987). Aetolian Foreign Relations During the Era of Expansion, Ca. 300–217 B.C. University of California, Berkeley. p. 104.

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). "Galatian language". In John T. Koch (ed.). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. Vol. III: G—L. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 788. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

Late classical sources—if they are to be trusted—suggest that it survived at least into the 6th century AD.

- ^ "France: The Roman conquest". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

Because of chronic internal rivalries, Gallic resistance was easily broken, though Vercingetorix's Great Rebellion of 52 bce had notable successes.

- ^ "Julius Caesar: The first triumvirate and the conquest of Gaul". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

Indeed, the Gallic cavalry was probably superior to the Roman, horseman for horseman. Rome's military superiority lay in its mastery of strategy, tactics, discipline, and military engineering. In Gaul, Rome also had the advantage of being able to deal separately with dozens of relatively small, independent, and uncooperative states. Caesar conquered these piecemeal, and the concerted attempt made by a number of them in 52 bce to shake off the Roman yoke came too late.

- ^ Strauss, Barry (2009). The Spartacus War. Simon and Schuster. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-4165-3205-7.

- ^ Marcellinus, Ammianus (1862). The roman history of Ammianus Marcellinus: during the reigns of the emperors Constantius, Julian, Jovianus, Valentinian, and Valens, Volume 1. H. G. Bohn. p. 80. ISBN 9780141921501. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ James Bromwich. "The Roman Remains of Northern and Eastern France: A Guidebook." P. 341. Citing "Bibliotheca Historica," 5.28, 1–3.

- ^ Gaius Petronius, "Satyricon", 1st century AD, p. 208.

- ^ a b Megaw, 30

- ^ Megaw, 40

- ^ Megaw, 34–39; Sandars, 223–225; Laing, chapter 2

- ^ Wallace, 126

- ^ Sandars, 226–233; Laing, 34–35

- ^ "Gallic Wars" I.1.

- ^ Stifter, David (2012). "Old Celtic Languages (lecture notes)". University of Kopenhagen. p. 109.

- ^ a b Laurence Hélix (2011). Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5.

Le déclin du Gaulois et sa disparition ne s'expliquent pas seulement par des pratiques culturelles spécifiques: Lorsque les Romains conduits par César envahirent la Gaule, au 1er siecle avant J.-C., celle-ci romanisa de manière progressive et profonde. Pendant près de 500 ans, la fameuse période gallo-romaine, le gaulois et le latin parlé coexistèrent; au VIe siècle encore; le temoignage de Grégoire de Tours atteste la survivance de la langue gauloise.

- ^ a b Savignac, Jean-Paul (2004). Dictionnaire Français-Gaulois. Paris: La Différence. p. 26.

- ^ a b Matasovic, Ranko (2007). "Insular Celtic as a Language Area". The Celtic Languages in Contact (Papers from the Workshop within the Framework of the XIII International Congress of Celtic Studies). Potsdam University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-3-940793-07-2.

- ^ Henri Guiter, "Sur le substrat gaulois dans la Romania", in Munus amicitae. Studia linguistica in honorem Witoldi Manczak septuagenarii, eds., Anna Bochnakowa & Stanislan Widlak, Krakow, 1995.

- ^ Eugeen Roegiest, Vers les sources des langues romanes: Un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania (Leuven, Belgium: Acco, 2006), 83.

- ^ Adams, J. N. "Chapter V – Regionalisms in provincial texts: Gaul". The Regional Diversification of Latin 200 BC – AD 600. Cambridge. pp. 279–289. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511482977.006.

- ^ Polinsky, Maria; Van Everbroeck, Ezra (2003). "Development of Gender Classifications: Modeling the Historical Change from Latin to French". Language. 79 (2): 356–390. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.134.9933. doi:10.1353/lan.2003.0131. JSTOR 4489422. S2CID 6797972.

- ^ a b c d e f Cunliffe, Barry (2018) [1997]. "Chapter 11: Religious systems". The Ancient Celts (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 275–277, 286, 291–296.

- ^ a b c Green, Miranda (2012). "Chapter 25: The Gods and the supernatural", The Celtic World. Routledge. pp. 465–485

- ^ a b c d e Koch, John (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1488–1491.

- ^ Sjoestedt, Marie-Louise (originally published in French, 1940, reissued 1982). Gods and Heroes of the Celts. Translated by Myles Dillon, Turtle Island Foundation ISBN 0-913666-52-1, pp. 16, 24–46.

- ^ Inse Jones, Prudence, and Nigel Pennick. History of pagan Europe. London: Routledge, 1995. Print.

- ^ Koch (2006), p. 850

- ^ Sjoestedt (1982) pp. xxvi–xix.

- ^ Green, Miranda (2002). Animals in Celtic Life and Myth. Routledge. pp. 94–96.

- ^ Koch, John (2012). The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 687–690. ISBN 978-1598849646.

- ^ Salma Ghezal, Elsa Ciesielski, Benjamin Girard, Aurélien Creuzieux, Peter Gosnell, Carole Mathe, Cathy Vieillescazes, Réjane Roure (2019), "Embalmed heads of the Celtic Iron Age in the south of France", Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 101, pp. 181–188, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.09.011.

- ^ "The Gauls really did embalm the severed heads of enemies, research shows". The Guardian. 7 November 2018.

- ^ Bouillet, Marie-Nicolas; Chassang, Alexis (1878), Dictionnaire universel d'histoire et de géographie [Universal Dictionary of History and Geography] (printed monograph) (in French) (26th ed.), Paris: Hachette, p. 1905, retrieved July 16, 2013,

Peuple de la Gaule Narbonnaise entre les Allobroges au N. et les Segalauni au S., avait pour capit. Augusta Tricastinorum (Aoust-en-Diois)

- ^ "Pour moi, l'histoire de France commence avec Clovis, choisi comme roi de France par la tribu des Francs, qui donnèrent leur nom à la France. Avant Clovis, nous avons la Préhistoire gallo-romaine et gauloise. L'élément décisif pour moi, c'est que Clovis fut le premier roi à être baptisé chrétien. Mon pays est un pays chrétien et je commence à compter l'histoire de France à partir de l'accession d'un roi chrétien qui porte le nom des Francs." Cited in the biography by David Schœnbrun, 1965.

- ^ Les Romains qui vinrent s'établir en Gaule étaient en petit nombre. Les Francs n'étaient pas nombreux non plus, Clovis n'en avait que quelques milliers avec lui. Le fond de notre population est donc resté gaulois. Les Gaulois sont nos ancêtres." (cours moyen, p. 26).

- ^ a b c d Fischer, Claire-Elise; et al. (2018). "The multiple maternal legacy of the Late Iron Age group of Urville-Nacqueville (France, Normandy) documents a long-standing genetic contact zone in northwestern France". PLOS One. 13 (12). PLOS: e0207459. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1307459F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207459. PMC 6283558. PMID 30521562.

- ^ a b c d e Fischer, Claire-Elise; et al. (2019). "Multi-scale archaeogenetic study of two French Iron Age communities: From internal social- to broad-scale population dynamics". Journal of Archaeological Science. 27 (101942). Elsevier: 101942. Bibcode:2019JArSR..27j1942F. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.101942.

- ^ Fischer, Claire-Elise; et al. (2022). "Origin and mobility of Iron Age Gaulish groups in present-day France revealed through archaeogenomics". iScience. 25 (4). Cell Press: 104094. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j4094F. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.104094. PMC 8983337. PMID 35402880.

Bibliography

- Blažek, Václav (2008). "Gaulish language". Studia Minora Facultatis Philosophicae Universitatis Brunensis. 13: 37–65. ISSN 0231-7710.

- Brunaux, Jean-Louis (2005). Les Gaulois. Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-41028-9.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2018). The Ancient Celts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-875292-9.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Derks, Ton (1998). Gods, Temples, and Ritual Practices: The Transformation of Religious Ideas and Values in Roman Gaul. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-254-3.

- Drinkwater, John F. (2014) [1983]. Roman Gaul: The Three Provinces, 58 BC–AD 260. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-75074-1.

- Fichtl, Stephan (2004). Les peuples gaulois: IIIe-Ier siècles av. J.-C. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-290-2.

- Green, Miranda (2012). The Celtic World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-63243-4.

- Koch, John T. (2012). The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-964-6.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1994). La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-089-2.

- Laing, Lloyd and Jenifer. Art of the Celts, Thames and Hudson, London 1992 ISBN 0-500-20256-7

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. ISBN 9789004173361.

- Megaw, Ruth and Vincent, Celtic Art, 2001, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28265-X

- Sandars, Nancy K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art), 1968 (nb 1st edn.)

- Williams, J. H. C. (2001). Beyond the Rubicon: Romans and Gauls in Republican Italy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815300-9.

- Wallace, Patrick F., O'Floinn, Raghnall eds. Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities ISBN 0-7171-2829-6

Further reading

- Villani, Paola. "About the Kassites also known as the Gauls and then gens Cassia." International Journal of Archaeology 1.2 (2013): 1–13.

- Barlow, Jonathan (1998). Julius Caesar as Artful Reporter: The War Commentaries as Political Instruments. Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-2859-1.

- Barruol, Guy (1969). Les Peuples préromains du Sud-Est de la Gaule: étude de géographie historique. E. de Boccard. OCLC 3279201.

- Brogan, Olwen (1953). Roman Gaul. Harvard University Press. OCLC 876050141.

- Brunaux, Jean-Louis; Lambot, Bernard (1987). Guerre et armement chez les Gaulois: 450–52 av. J.-C. Errance. ISBN 978-2-903442-62-0.

- Brunaux, Jean-Louis (1996). Les religions gauloises: rituels celtiques de la Gaule indépendante. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-128-8.

- Brunaux, Jean-Louis (2004). Guerre et religion en Gaule: essai d'anthropologie celtique. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-259-9.

- Chevallier, Raymond (1983). La romanisation de la Celtique du Pô. Essai d'histoire provinciale. Vol. 249. Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises d'Athènes et de Rome. ISBN 978-2728300488.

- Chilver, G. E. F. (1941). Cisalpine Gaul: Social and Economic History from 49 B.C. to the Death of Trajan. Clarendon Press. OCLC 1120882705.

- Dottin, Georges (1918). La langue gauloise: grammaire, textes et glossaire. C. Klincksieck. OCLC 609773108.

- Drinkwater, John F.; Elton, Hugh (2002). Fifth-Century Gaul: A Crisis of Identity?. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52933-4.

- Ebel, Charles (1976). Transalpine Gaul: The Emergence of a Roman Province. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04384-8.

- Evans, D. Ellis (1967). Gaulish Personal Names: A Study of Some Continental Celtic Formations. Clarendon Press. OCLC 468437906.

- Hatt, Jean-Jacques (1966). Histoire de la Gaule romaine (120 avant J.-C.-451 aprés J.-C.), colonisation ou colonialisme?. Payot.

- Jullian, Camille (1908). Histoire de la Gaule. Hachette. OCLC 463155800.

- King, Anthony (1990). Roman Gaul and Germany. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06989-3.

- Kruta, Venceslas (2000). Les Celtes, histoire et dictionnaire : des origines à la romanisation et au christianisme. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-05690-6.

- Mathisen, Ralph W. (1993). Roman Aristocrats in Barbarian Gaul: Strategies for Survival in an Age of Transition. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-75806-3.

- Mullen, Alex (2013). Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean: Multilingualism and Multiple Identities in the Iron Age and Roman Periods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-34165-4.

- Rivet, A. L. F. (1988). Gallia Narbonensis: With a Chapter on Alpes Maritimae : Southern France in Roman Times. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5860-2.

- Thévenot, Emile (1987). Histoire des Gaulois. Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-067863-2.

- Van Dam, Raymond (1992). Leadership and Community in Late Antique Gaul. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07895-6.

- Whatmough, Joshua (1950). The Dialects of Ancient Gaul: Prolegomena and Records of the Dialects. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-20280-1.

- Wightman, Edith M. (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05297-0.

- Woolf, Greg (1998). Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41445-6.

External links

- Acy-Romance, the Gauls of Ardennes Archived 2014-05-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Lattes, Languedoc and the Southern Gauls Archived 2016-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- The Gauls in Provence: the Oppidum of Entremont Archived 2016-04-02 at the Wayback Machine