Gambling and information theory

Statistical inference might be thought of as gambling theory applied to the world around us. The myriad applications for logarithmic information measures tell us precisely how to take the best guess in the face of partial information.[1] In that sense, information theory might be considered a formal expression of the theory of gambling. It is no surprise, therefore, that information theory has applications to games of chance.[2]

Kelly Betting

Kelly betting or proportional betting is an application of information theory to investing and gambling. Its discoverer was John Larry Kelly, Jr.

Part of Kelly's insight was to have the gambler maximize the expectation of the logarithm of his capital, rather than the expected profit from each bet. This is important, since in the latter case, one would be led to gamble all he had when presented with a favorable bet, and if he lost, would have no capital with which to place subsequent bets. Kelly realized that it was the logarithm of the gambler's capital which is additive in sequential bets, and "to which the law of large numbers applies."

Side information

A bit is the amount of entropy in a bettable event with two possible outcomes and even odds. Obviously we could double our money if we knew beforehand what the outcome of that event would be. Kelly's insight was that no matter how complicated the betting scenario is, we can use an optimum betting strategy, called the Kelly criterion, to make our money grow exponentially with whatever side information we are able to obtain. The value of this "illicit" side information is measured as mutual information relative to the outcome of the betable event:

where Y is the side information, X is the outcome of the betable event, and I is the state of the bookmaker's knowledge. This is the average Kullback–Leibler divergence, or information gain, of the a posteriori probability distribution of X given the value of Y relative to the a priori distribution, or stated odds, on X. Notice that the expectation is taken over Y rather than X: we need to evaluate how accurate, in the long term, our side information Y is before we start betting real money on X. This is a straightforward application of Bayesian inference. Note that the side information Y might affect not just our knowledge of the event X but also the event itself. For example, Y might be a horse that had too many oats or not enough water. The same mathematics applies in this case, because from the bookmaker's point of view, the occasional race fixing is already taken into account when he makes his odds.

The nature of side information is extremely finicky. We have already seen that it can affect the actual event as well as our knowledge of the outcome. Suppose we have an informer, who tells us that a certain horse is going to win. We certainly do not want to bet all our money on that horse just upon a rumor: that informer may be betting on another horse, and may be spreading rumors just so he can get better odds himself. Instead, as we have indicated, we need to evaluate our side information in the long term to see how it correlates with the outcomes of the races. This way we can determine exactly how reliable our informer is, and place our bets precisely to maximize the expected logarithm of our capital according to the Kelly criterion. Even if our informer is lying to us, we can still profit from his lies if we can find some reverse correlation between his tips and the actual race results.

Doubling rate

Doubling rate in gambling on a horse race is [3]

where there are horses, the probability of the th horse winning being , the proportion of wealth bet on the horse being , and the odds (payoff) being (e.g., if the th horse winning pays double the amount bet). This quantity is maximized by proportional (Kelly) gambling:

for which

where is information entropy.

Expected gains

An important but simple relation exists between the amount of side information a gambler obtains and the expected exponential growth of his capital (Kelly):

for an optimal betting strategy, where is the initial capital, is the capital after the tth bet, and is the amount of side information obtained concerning the ith bet (in particular, the mutual information relative to the outcome of each betable event).

This equation applies in the absence of any transaction costs or minimum bets. When these constraints apply (as they invariably do in real life), another important gambling concept comes into play: in a game with negative expected value, the gambler (or unscrupulous investor) must face a certain probability of ultimate ruin, which is known as the gambler's ruin scenario. Note that even food, clothing, and shelter can be considered fixed transaction costs and thus contribute to the gambler's probability of ultimate ruin.

This equation was the first application of Shannon's theory of information outside its prevailing paradigm of data communications (Pierce).

Applications for self-information

The logarithmic probability measure self-information or surprisal,[4] whose average is information entropy/uncertainty and whose average difference is KL-divergence, has applications to odds-analysis all by itself. Its two primary strengths are that surprisals: (i) reduce minuscule probabilities to numbers of manageable size, and (ii) add whenever probabilities multiply.

For example, one might say that "the number of states equals two to the number of bits" i.e. #states = 2#bits. Here the quantity that's measured in bits is the logarithmic information measure mentioned above. Hence there are N bits of surprisal in landing all heads on one's first toss of N coins.

The additive nature of surprisals, and one's ability to get a feel for their meaning with a handful of coins, can help one put improbable events (like winning the lottery, or having an accident) into context. For example if one out of 17 million tickets is a winner, then the surprisal of winning from a single random selection is about 24 bits. Tossing 24 coins a few times might give you a feel for the surprisal of getting all heads on the first try.

The additive nature of this measure also comes in handy when weighing alternatives. For example, imagine that the surprisal of harm from a vaccination is 20 bits. If the surprisal of catching a disease without it is 16 bits, but the surprisal of harm from the disease if you catch it is 2 bits, then the surprisal of harm from NOT getting the vaccination is only 16+2=18 bits. Whether or not you decide to get the vaccination (e.g. the monetary cost of paying for it is not included in this discussion), you can in that way at least take responsibility for a decision informed to the fact that not getting the vaccination involves more than one bit of additional risk.

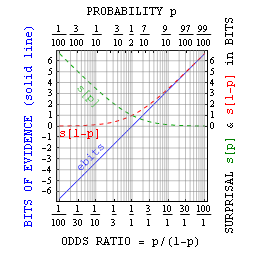

More generally, one can relate probability p to bits of surprisal sbits as probability = 1/2sbits. As suggested above, this is mainly useful with small probabilities. However, Jaynes pointed out that with true-false assertions one can also define bits of evidence ebits as the surprisal against minus the surprisal for. This evidence in bits relates simply to the odds ratio = p/(1-p) = 2ebits, and has advantages similar to those of self-information itself.

Applications in games of chance

Information theory can be thought of as a way of quantifying information so as to make the best decision in the face of imperfect information. That is, how to make the best decision using only the information you have available. The point of betting is to rationally assess all relevant variables of an uncertain game/race/match, then compare them to the bookmaker's assessments, which usually comes in the form of odds or spreads and place the proper bet if the assessments differ sufficiently.[5] The area of gambling where this has the most use is sports betting. Sports handicapping lends itself to information theory extremely well because of the availability of statistics. For many years noted economists have tested different mathematical theories using sports as their laboratory, with vastly differing results.

One theory regarding sports betting is that it is a random walk. Random walk is a scenario where new information, prices and returns will fluctuate by chance, this is part of the efficient-market hypothesis. The underlying belief of the efficient market hypothesis is that the market will always make adjustments for any new information. Therefore no one can beat the market because they are trading on the same information from which the market adjusted. However, according to Fama,[6] to have an efficient market three qualities need to be met:

- There are no transaction costs in trading securities

- All available information is costlessly available to all market participants

- All agree on the implications of the current information for the current price and distributions of future prices of each security

Statisticians have shown that it's the third condition which allows for information theory to be useful in sports handicapping. When everyone doesn't agree on how information will affect the outcome of the event, we get differing opinions.

See also

References

- ^ Jaynes, E.T. (1998/2003) Probability Theory: The Logic of Science (Cambridge U. Press, New York).

- ^ Kelly, J. L. (1956). "A New Interpretation of Information Rate" (PDF). Bell System Technical Journal. 35 (4): 917–926. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1956.tb03809.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Thomas M. Cover, Joy A. Thomas. Elements of information theory, 1st Edition. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1991. ISBN 0-471-06259-6, Chapter 6.

- ^ Tribus, Myron (1961) Thermodynamics and Thermostatics: An Introduction to Energy, Information and States of Matter, with Engineering Applications (D. Van Nostrand Company Inc., 24 West 40 Street, New York 18, New York, U.S.A) ASIN: B000ARSH5S.

- ^ Hansen, Kristen Brinch. (2006) Sports Betting from a Behavioral Finance Point of View Archived 2018-09-20 at the Wayback Machine (Arhus School of Business).

- ^ Fama, E.F. (1970) "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Independent Work", Journal of Financial Economics Volume 25, 383-417

![{\displaystyle W(b,p)=\mathbb {E} [\log _{2}S(X)]=\sum _{i=1}^{m}p_{i}\log _{2}b_{i}o_{i}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7709e5610bd7a212201e0e6ff5219ed4468515bd)