Gaithersburg, Maryland

Gaithersburg, Maryland | |

|---|---|

Top to bottom, left to right: the NIST Advanced Measurement Laboratory, the Gaithersburg city hall, a row of Gaithersburg townhouses, the Saint Rose of Lima Catholic Church, the John A. Belt Building, and the Washingtonian Waterfront | |

| Nickname: "Gburg" | |

| Motto: "A Character Counts! city" | |

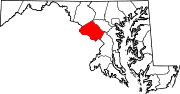

Location in Montgomery County and Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°7′55″N 77°13′35″W / 39.13194°N 77.22639°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Settled (as Log Town) | 1765 |

| Founded | 1802 |

| Incorporated (as a town) | April 5, 1878 |

| Ascension (to city status) | 1968[1] |

| Named for | Benjamin Gaither |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jud Ashman[2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 10.44 sq mi (27.05 km2) |

| • Land | 10.32 sq mi (26.73 km2) |

| • Water | 0.12 sq mi (0.32 km2) |

| Elevation | 350 ft (110 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 69,657 |

| • Density | 6,749.06/sq mi (2,605.78/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Area codes | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-31175 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2390591[4] |

| Website | gaithersburgmd |

Gaithersburg (/ˈɡeɪθərzbɜːrɡ/ GAY-thərz-burg) is a city in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. At the time of the 2020 census, Gaithersburg had a population of 69,657, making it the ninth-most populous community in the state.[5] Gaithersburg is located to the northwest of Washington, D.C., and is considered a suburb and a primary city within the Washington metropolitan area. Gaithersburg was incorporated as a town in 1878 and as a city in 1968.

Gaithersburg is located east and west of Interstate 270. The eastern section includes the historic area of the town. Landmarks and buildings from that time can still be seen in many places but especially in the historic central business district of Gaithersburg called "Olde Towne". The east side also includes City Hall, the Montgomery County Fairgrounds, and Bohrer Park (a well-known joint community recreation center and outdoor water park for kids and families). The west side of the city has many wealthier neighborhoods that were designed with smart growth techniques and embrace New Urbanism. These include the Kentlands community, the Lakelands community, and the Washingtonian Center (better known as Rio), a shopping/business district. Two New Urbanism communities are under construction, including Watkins Mill Town Center (Casey East and West), and the massive "Science City"[citation needed]. The state has a bus rapid transit line, Corridor Cities Transitway or "CCT", planned for the western portion of the city starting at Shady Grove Metro Station and connecting all the high-density western Gaithersburg neighborhoods with a total of eight stops planned in the city.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is headquartered in Gaithersburg directly west of I-270.[N 1] Other major employers in the city include IBM, Lockheed Martin Information Systems and Global Services business area headquarters, AstraZeneca. Gaithersburg is also the location of the garrison of the United States Army Reserve Legal Command.

Gaithersburg is noted for its ethnic and economic diversity; it was ranked second for ethnic diversity among the 501 largest U.S. cities, and first among smaller U.S. cities, by WalletHub in 2021.[6][7] In 2023, Wallethub announced that Gaithersburg was back in the number one spot for diversity in the U.S.[8]

History

Gaithersburg was settled in 1765 as a small agricultural settlement known as Log Town near the present day Summit Hall on Ralph Crabb's 1725 land grant "Deer Park".[9] The northern portion of the land grant was purchased by Henry Brookes, and he built his brick home "Montpelier" there, starting first with a log cabin in 1780/3. This 1,000-acre tract became part of the landmark IBM Headquarters complex built on the then-new I-270 Interstate "Industrial", now "Technology", Corridor in the late 1960s to the 1970s. Benjamin Gaither married Henry's daughter Margaret, and Benjamin and Margaret inherited a portion of Henry's land prior to Henry's death in 1807. Gaither built his home on the land in 1802.[10] By the 1850s the area had ceased to be called Log Town and was known to inhabitants as Gaithersburg.[11]

19th century

The Forest Oak Post Office, named for a large tree in the town, was located in Gaither's store in 1851.

On July 10, 1864, using the route of present-day 355, over 10,000 Confederate troops camped overnight in the area, including the present Bohrer Park, after a one-day march from Frederick after the Battle of Monocacy. The next day the troops continued towards Washington in an unsuccessful attempt to take the city.

When the railroad was built through town in 1873, the new station was called Gaithersburg, an officially recognized name for the community for the first time. Also in 1873 the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad constructed a station at Gaithersburg,[9] designed by Ephraim Francis Baldwin as part of his well-known series of Victorian stations in Maryland.[12] Rapid growth occurred shortly thereafter, and on April 5, 1878, the town was officially incorporated as the Town of Gaithersburg.

Gaithersburg boomed during the late 19th century and churches, schools, a mill, grain elevators, stores, and hotels were built. Much of this development focused around the railroad station.[11]

In 1899, Gaithersburg was selected as one of six global locations for the construction of an International Latitude Observatory as part of a project to measure the Earth's wobble on its polar axis. The Gaithersburg Latitude Observatory is (as of 2007) the only National Historic Landmark in the City of Gaithersburg. The observatory and five others in Japan, Italy, Russia, and the United States gathered information that is still used by scientists today, along with information from satellites, to determine polar motion; the size, shape, and physical properties of the earth; and to aid the space program through the precise navigational patterns of orbiting satellites. The Gaithersburg station operated until 1982 when computerization rendered the manual observation obsolete.

Late 20th century

In 1968, Gaithersburg was upgraded from a town to a city.

Gaithersburg remained a predominantly rural farm town until the 1970s when more construction began. As the population grew, with homes spreading throughout the area, Gaithersburg began taking on a suburban and semi-urban feel, leaving its farming roots behind. During the late 1990s and 2000s, it had become one of the most economically and ethnically diverse areas in the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area as well as the State of Maryland, with people from all walks of life calling Gaithersburg home. This can be seen in the local schools, with Gaithersburg High School and Watkins Mill High School having two of the most diverse student bodies in the region.

During a 1997 rainstorm, the 295-year-old forest oak tree that gave its name to the Forest Oak Post Office crashed down.[13] The tree served as the inspiration for the city's logo,[13] which is also featured prominently on the city's flag.[13]

21st century

In 2007, parts of the film Body of Lies were filmed in the city, at a building on 100 Edison Park Drive. The film was released in 2008 and the building is now the Montgomery County Police Department's headquarters.[14]

On July 16, 2010, Gaithersburg was part of the area where a 3.6 magnitude earthquake was felt, one of the strongest to occur in Maryland.

After years of decline and loss of tenants, including three of its four anchor stores in 2019, Lakeforest Mall closed on March 31, 2023,[15] with plans to demolish it and redevelop the area.[16]

Gaithersburg is also the location of the United States Army Reserve Legal Command.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.34 square miles (26.78 km2), of which 10.20 square miles (26.42 km2) is land and 0.14 square miles (0.36 km2) is water.[17]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 547 | — | |

| 1910 | 625 | 14.3% | |

| 1920 | 729 | 16.6% | |

| 1930 | 1,068 | 46.5% | |

| 1940 | 1,021 | −4.4% | |

| 1950 | 1,755 | 71.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,847 | 119.2% | |

| 1970 | 8,344 | 116.9% | |

| 1980 | 26,424 | 216.7% | |

| 1990 | 39,542 | 49.6% | |

| 2000 | 52,613 | 33.1% | |

| 2010 | 59,933 | 13.9% | |

| 2020 | 69,657 | 16.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] 2010–2020[5] | |||

2022 ACS

As of the 2022 American Community Survey, there were 68,952 people and 24,523 households in the town. The racial makeup of the town was 33% White, 13% Black, 15% Asian, and 1% from other races. Hispanic people of any race were 36% of the population.

The median household income was 95,453, and 6% of people were under the poverty line.

The average time to work was 30 minutes, 57% of people drove alone, 11% carpooled, 8% took public transit, 1% biked, 2% walked and 20% work from home.[19]

2010 census

As of the census[20] of 2010, there were 59,933 people, 22,000 households, and 14,548 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,875.8 inhabitants per square mile (2,268.7/km2). There were 23,337 housing units at an average density of 2,287.9 per square mile (883.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 31.9% non-Hispanic White, 16.3% African American, 0.5% Native American, 16.9% Asian (6.01 Chinese, 4.77% Indian, 2.03% Korean, 1.69% Filipino, 1.02% Vietnamese, 0.62% Burmese), 0.1% Pacific Islander, 10.7% from other races, and 4.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 24.2% of the population (8.3% Salvadoran, 2% Honduran, 1.9% Mexican, 1.9% Peruvian, 1.7% Guatemalan).

There were 22,000 households, of which 37.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.3% were married couples living together, 12.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 33.9% were non-families. 26.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 3.24.

The median age in the city was 35.1 years. 24.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 7.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 33.8% were from 25 to 44; 24.6% were from 45 to 64; and 9.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.6% male and 51.4% females.

2000 census

As of the census[21] of 2000, there were 52,613 people, 19,621 households, and 12,577 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,216.2 inhabitants per square mile (2,014.0/km2). There were 20,674 housing units at an average density of 2,049.7 per square mile (791.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city is 34.7% White, 19.5% Black or African American, 0.2% Native American, 13.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 3.6% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. 24.8% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 34.3% of Gaithersburg's population was foreign-born.

There were 19,621 households, out of which 34.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.6% were married couples living together, 11.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.9% were non-families. 27.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.65 and the average family size was 3.14 the population was spread out, with 25.0% under the age of 18, 9.0% from 18 to 24, 37.7% from 25 to 44, 20.0% from 45 to 64, and 8.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.4 males.

Economy

According to the city's 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[22] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AstraZeneca (formerly MedImmune) | 4,000 |

| 2 | National Institute of Standards and Technology | 2,798 |

| 3 | Leidos (merged with Lockheed Martin) | 1,515 |

| 4 | Asbury Methodist Village | 771 |

| 5 | Hughes Network Systems, LLC | 729 |

| 6 | Sodexo USA | 536 |

| 7 | Adventist HealthCare | 495 |

| 8 | GeneDx | 350 |

| 9 | Kaiser Permanente | 350 |

| 10 | Emergent BioSolutions | 347 |

Gaithersburg also receives significant income from its conference organization platform including prominent conferences such as the CHI 84 conference.

Patton Electronics was founded in Gaithersburg during 1984. [23]

Government

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 77.5% 21,286 | 20.0% 5,487 | 2.5% 694 |

| 2016 | 75.2% 18,987 | 19.1% 4,820 | 5.7% 1,430 |

Gaithersburg has an elected, five-member City Council, which serves as the legislative body of the city. The mayor, who is also elected, serves as non-voting president of the council. The day-to-day administration of the city is overseen by a career city manager.

The city's current mayor is Jud Ashman, who has held the office since 2014. On October 6, 2014, the Gaithersburg City Council selected city council member Jud Ashman to serve as mayor until the next City of Gaithersburg election in November 2015, replacing resigning mayor Sidney Katz. Ashman was re-elected in November 2015 and would be re-elected to full terms in 2017 and 2021.[25]

| Position | Name | In office since |

Next Election |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mayor | Jud Ashman | 2015 | 2025 |

| Council (At Large) | Lisa Henderson | 2021 | 2025 |

| Council (At Large) | Jim McNulty | 2021 | 2025 |

| Council (At Large) | Neil Harris | 2014 | 2027 |

| Council (At Large) | Yamil Hernández | 2023 | 2027 |

| Council (At Large) | Robert Wu | 2015 | 2027 |

Previous mayors include:

- George W. Meem 1898–1904

- Carson Ward 1904–1906

- John W. Walker 1906–1908

- E. D. Kingsley 1908–1912

- Richard H. Miles 1912–1918

- John W. Walker 1918–1924

- Walter M. Magruder 1924–1926

- William McBain 1926–1948

- Harry C. Perry, Sr. 1948–1954

- Merton F. Duvall 1954–1966

- John W. Griffith 1966–1967

- Harold C. Morris 1967–1974

- Susan E. Nicholson, May–September 1974

- Milton M. Walker 1974–1976

- B. Daniel Walder 1976–1978

- Bruce A. Goldensohn 1978–1986

- W. Edward Bohrer, Jr. 1986–1998

- Sidney A. Katz 1998 – 2014

- Jud Ashman, November 2014 – Present

The departments of the city of Gaithersburg and their directors include:

- Office of the City Manager, Tanisha R. Briley

- Finance and Administration, Janice Hartman

- Planning and Code Administration, John Schlichting

- Community, Neighborhood and Housing Services, Tom Lonergan-Seeger

- Human Resources, Kimberly Yocklin

- Information Technology, Ruth Lutero

- Parks, Recreation, and Culture, Carolyn Muller

- Chief of Police, Mark Sroka

- Public Works, Anthony Berger

Education

The following Montgomery County Public Schools are located in Gaithersburg:[26]

Elementary schools

- Brown Station

- Darnestown

- Diamond

- DuFief

- Fields Road

- Flower Hill

- Gaithersburg

- Goshen

- Harriet R. Tubman

- Jones Lane

- Judith A. Resnik

- Laytonsville

- Rachel Carson

- Rosemont

- South Lake

- Stedwick

- Strawberry Knoll

- Summit Hall

- Thurgood Marshall

- Washington Grove

- Watkins Mill

- Whetstone

- Woodfield

Middle schools

- Forest Oak

- Gaithersburg

- Lakelands Park Middle School

- Ridgeview

- Shady Grove

High schools

Media

Gaithersburg is primarily served by the Washington, D.C. media market.

Newspapers

- The Town Courier newspaper is based in Kentlands and focuses on Gaithersburg's west side neighborhoods, in addition to publishing Rockville and Urbana editions.

Infrastructure

Police

Being a city, Gaithersburg also has its own police department, which was created in 1963.[27]

Transportation

Roads and highways

The most prominent highways serving Gaithersburg are Interstate 270 and Interstate 370. I-270 is the main highway leading northwest out of metropolitan Washington, D.C., beginning at Interstate 495 (the Capital Beltway) and proceeding northwestward to Interstate 70 in Frederick. I-370 is a short spur, starting just west of I-270 in Gaithersburg and heading east to its junction with Maryland Route 200. Via MD 200, I-370 connects Gaithersburg with Interstate 95 near Laurel.

Maryland Route 355 was the precursor to I-270 and follows a parallel route. It now serves as the main commercial roadway through Gaithersburg and neighboring communities. Other state highways serving Gaithersburg include Maryland Route 117, Maryland Route 119 and Maryland Route 124. Maryland Route 28 passes just outside the Gaithersburg corporate limits.

Transit

Gaithersburg is connected to the Washington Metro via Shady Grove station, which is located just outside the city limits and is the north-western terminus of the Red Line.

The Corridor Cities Transitway is a proposed bus rapid transit line that would have 8 stops in Gaithersburg, generally in the western half of the city.

Maryland's MARC system operates commuter rail services connecting Gaithersburg to Washington, D.C., with two stations in the city, at Old Town Gaithersburg and Metropolitan Grove, and a third station — Washington Grove — just outside city limits.

Bus service in Gaithersburg consists of Metrobus routes operated by WMATA and Ride-On routes operated by Montgomery County, as well as paratransit service provided by MetroAccess.

Airport

Montgomery County Airpark is located 3 miles (5 km) northeast of the city.

Notable people

- Sankar Adhya, member of the National Academy of Sciences

- Utkarsh Ambudkar, actor, rapper

- Lawson Aschenbach, NASCAR driver

- Georges C. Benjamin, former secretary of the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

- Kimberly J. Brown, actress who starred in Halloweentown

- Mark Bryan, lead guitarist of Hootie & the Blowfish

- Isabel McNeill Carley, published music teacher, lived in Gaithersburg from 2004 until her death in 2011

- Justin Carter (born 1987), basketball player for Maccabi Kiryat Gat of the Israeli Premier League

- Kiran Chetry, CNN anchor

- Chris Coghlan, Major League Baseball player

- Jeanine Cummins, author

- Dominique Dawes, three-time women's Olympic gymnastics team member, member of the Magnificent Seven

- Stefon Diggs, football player for the Houston Texans

- Trevon Diggs, football player for the Dallas Cowboys

- Brandon Victor Dixon, American actor, singer and theatrical producer

- Astrid Ellena, Miss Indonesia 2011

- Hank Fraley, former football player in the NFL

- Judah Friedlander, actor, most notably from the television show 30 Rock

- Jake Funk, football player for the Los Angeles Rams and Super Bowl LVI champion

- Joshua Harris, author and former Christian pastor

- Dwayne Haskins, NFL quarterback for the Pittsburgh Steelers

- Matt Holt, former singer of Nothingface and Kingdom of Snakes

- Paul James, actor, most notably from the television show Greek

- Kelela, R&B singer

- Courtney Kupets, 2004 Olympic gymnast and three-time NCAA champion

- Tim Kurkjian, ESPN baseball analyst, appears on SportsCenter and Baseball Tonight

- Charles Lee, Charlotte Hornets head coach

- Matthew Lesko, author of Free Money from the government books

- Logic (Robert Bryson Hall II), hip hop musician, rapper, musical engineer

- Lucas and Marcus, dancers and YouTube personalities

- Shane McMahon, WWE wrestler and commissioner of WWE SmackDown Live

- Jim Miklaszewski, chief Pentagon correspondent for NBC News

- Malcolm Miller, basketball player and NBA champion for the Toronto Raptors

- Nick Mullen, a comedian

- John Papuchis, college football coach

- Andrew Platt, former Maryland House of Delegates member

- Guy Prather, football player

- Paul Rabil, lacrosse player (midfield), four-time All-American at Johns Hopkins University

- Eddie Stubbs, country musician, disc jockey, and Grand Ole Opry announcer

- Jodie Turner-Smith, actress and model[28]

- Wale, hip hop musician and rapper

- Jessica Watkins, NASA astronaut

- David P. Weber, former assistant inspector general for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

- James White, basketball player who played for the San Antonio Spurs and Houston Rockets

- Frederick Yeh, biologist and animal welfare activist

- 6ix, record producer

- Chop Robinson defensive end for the Miami Dolphins

In popular culture

- Part of the 2006 film Borat was filmed in Gaithersburg in 2005.[29]

- Part of an episode of Da Ali G Show was filmed in Gaithersburg in 2004.[30]

- It is mentioned by character Fox Mulder in episodes of The X-Files and as a story location.[31][32][33]

- Some of The Blair Witch Project was filmed in Seneca Creek State Park[34]

Notes

- ^ Although NIST's mailing address states Gaithersburg, and the City of Gaithersburg surrounds NIST's property, the land where NIST is situated is not incorporated into the City of Gaithersburg. Instead, it is in an unincorporated part of Montgomery County. Owing to how land has been added to Gaithersburg over the years, there are multiple such unincorporated enclaves within the perimeter; see the City's Zoning Map for details (3MB PDF).

References

- ^ "A Master Plan Element" (PDF). Maryland: City of Gaithersburg. October 5, 2007. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ "Mayor & City Council". www.gaithersburgmd.gov. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Gaithersburg, Maryland

- ^ a b "QuickFacts: Gaithersburg city, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Zumer, Bryna (April 19, 2021). "2 Montgomery County cities ranked among most diverse in the U.S." Fox 5 News. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ "4 Maryland cities in top 10 for most culturally diverse cities in U.S., according to WalletHub". Fox 5 DC. February 17, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ "This Maryland city was named 'most diverse' in United States: Report". April 23, 2023.

- ^ a b

- Eddy, Kristin (September 17, 1987). "Md. Offers Two Fairs for Sunday". The Washington Post. p. M09.

- Eddy, Kristin (September 17, 1987). "Md. Offers Two Fairs for Sunday". The Washington Post. p. M09.

- ^ "20,000 Expected to Wish Gaithersburg Happy Birthday". The Washington Post. September 4, 1950. p. 3.

- ^ a b Offutt, William; Sween, Jane (1999). Montgomery County: Centuries of Change. American Historical Press. pp. 166–167.

- ^ "Gaithersburg Station". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. October 17, 1985. p. MDA4. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c Vogel, Steve (June 28, 1997). "Gaithersburg Tree Goes Down in History: Storm Fells City's Famed Forest Oak". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. B1. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016.

- ^ Robinson, Chris (March 17, 2015). "Spy thriller brings a touch of Hollywood to the county". Gazette.Net. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015.

- ^ Tyko, Kelly (January 5, 2023). "Macy's stores closing 2023: Liquidation sales to start in January". Axios. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Demo/Construction at Lakeforest has 2024 Target Date; Dining Area With Boardwalk in the Early Plans - The MoCo Show". The MoCo Show. October 20, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Gaithersburg, MD - Profile data - Census Reporter". March 20, 2024. Archived from the original on March 20, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "FY 2020 City of Gaithersburg, MD Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Patton Electronics - Products, Competitors, Financials, Employees, Headquarters Locations". www.cbinsights.com.

- ^ "Dave's Redistricting". Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ "Council Member Jud Ashman Selected as Mayor of Gaithersburg". www.gaithersburgmd.gov.

- ^ "List of Schools" (PDF). Montgomery County Public Schools. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "Police Department History". Maryland: City of Gaithersburg. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ Perry, Kevin EG (April 29, 2021). "Jodie Turner-Smith: "The last three years of my life have been completely mad"". NME. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ "Accidental Stars of 'Borat' Want the Last Laugh". ABC News. November 13, 2006.

- ^ "Gaithersburg detective appears on HBO comedy show". www.gazette.net.

- ^ "The Erlenmeyer Flask – 1X23". www.insidethex.co.uk.

- ^ "All Souls – 5X17". www.insidethex.co.uk.

- ^ "The End – 5X20". www.insidethex.co.uk.

- ^ "Tour The Locations Where 'The Blair Witch Project' Was Filmed". CBS News. October 22, 2019.

Further reading

- Curtis, Shaun (2010). Then and Now: Gaithersburg. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-8551-2. LCCN 2009936602. OCLC 500822779.

- Curtis, Shaun (2020). Around Gaithersburg. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1467104623.

- Myers, Brian (2020). Greater than a Tourist: Gaithersburg, Maryland. Loch Haven, Pennsylvania: CZYK Publishing. ISBN 979-8643248019.

External links

- Official website

- a photographic tour of the city's history Archived August 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine