Output gap

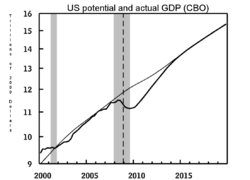

The GDP gap or the output gap is the difference between actual GDP or actual output and potential GDP, in an attempt to identify the current economic position over the business cycle. The measure of output gap is largely used in macroeconomic policy (in particular in the context of EU fiscal rules compliance). The GDP gap is a highly criticized notion, in particular due to the fact that the potential GDP is not an observable variable, it is instead often derived from past GDP data, which could lead to systemic downward biases.[3][4][5][6]

Calculation

The calculation for the output gap is (Y–Y*)/Y* where Y is actual output and Y* is potential output. If this calculation yields a positive number it is called an inflationary gap and indicates the growth of aggregate demand is outpacing the growth of aggregate supply—possibly creating inflation; if the calculation yields a negative number it is called a recessionary gap—possibly signifying deflation.[7]

The percentage GDP gap is the actual GDP minus the potential GDP divided by the potential GDP.

- .

For example, February 2013 data from the Congressional Budget Office showed that the United States had a projected output gap for 2013 of roughly $1 trillion, or nearly 6% of potential GDP.[8]

Using approximation, the following equation holds.

Okun's law: the relationship between GDP gap and unemployment

Okun's law is based on regression analysis of U.S. data that shows a correlation between unemployment and GDP gap. Okun's law can be stated as: For every 1% increase in cyclical unemployment (actual rate of unemployment – natural rate of unemployment), GDP gap will decrease by β%.

- %GDP gap = −β x %Cyclical unemployment

This can also be expressed as:

where:

- u is the actual rate of unemployment

- ū is the natural rate of unemployment

- β is a constant derived from regression to show the link between deviations from natural output and natural unemployment. β > 0.

Consequences of a large output gap

A persistent, large output gap has severe consequences for, among other things, a country's labor market, a country's long-run economic potential, and a country's public finances. First, the longer the output gap persists, the longer the labor market will underperform, as output gaps indicate that workers who would like to work are instead idled because the economy is not producing to capacity. The United States' labor market slack is evident in an October 2013 unemployment rate of 7.3 percent, compared with an average annual rate of 4.6 percent in 2007, before the brunt of the recession struck.[9]

Second, the longer a sizable output gap persists, the more damage will be inflicted on an economy's long-term potential through what economists term “hysteresis effects.” In essence, workers and capital remaining idle for long stretches due to an economy operating below its capacity can cause long-lasting damage to workers and the broader economy.[10] For example, the longer jobless workers remain unemployed, the more their skills and professional networks can atrophy, potentially rendering these workers unemployable. For the United States, this concern is especially salient given that the long-term unemployment rate—the share of the unemployed who have been out of work for more than six months—stood at 36.9 percent in September 2013.[11] Also, an underperforming economy can result in reduced investments in areas that pay dividends over the long term, such as education, and research and development. Such reductions are likely to impair an economy's long-run potential.

Third, a persistent, large output gap can have deleterious effects on a country's public finances. This is partially because a struggling economy with a weak labor market results in forgone tax revenue, as unemployed or underemployed workers are either paying no income taxes, or paying less in income taxes than they would if fully employed. Additionally, a higher incidence of unemployment increases public spending on safety-net programs (in the United States, these include unemployment insurance, food stamps, Medicaid, and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program). Reduced tax revenue and increased public spending both exacerbate budget deficits. Indeed, research has found that for each dollar U.S. gross domestic product moves away from potential output, U.S. cyclical budget deficits increase 37 cents.[12]

Controversy on the EU's output gap measurements

The calculations of the output gap by the European Commission has come under heavy criticism by a range of academics and think tanks, in large part fostered by Robin Brooks, chief economist of the prestigious Institute of International Finance, who have launched a "campaign against nonsense output gaps."[13][14] The criticism addressed to the European Commission include the complexity and contradictions in the methodology (which is in fact the one proposed by experts sitting in the "Output Gap Working Group" and approved by finance ministers in the ECOFIN meetings). Critics argue the methodology results in a highly pro-cyclical output gap indexes, and sometimes implausible outcomes, in particular in the case of Italy. [15]

In September 2019, several senior officials from the European Commission's including the Director General of the DG ECFIN, Mr Marco Buti, have written a joint article refuting this criticism.[16] But the critics said they remained unconvinced.[17][18][5]

See also

References

- ^ 100*(Real Gross Domestic Product-Real Potential Gross Domestic Product)/Real Potential Gross Domestic Product | FRED | St. Louis Fed

- ^ Real Potential Gross Domestic Product, Real Gross Domestic Product | FRED | St. Louis Fed

- ^ Barkema, Jelle; Gudmundsson, Tryggvi; Mrkaic, Mico (2020-12-06). "Output gaps in practice: Proceed with caution". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- ^ ""Output Gap Nonsense" and the EU's Fiscal Rules". Institute for New Economic Thinking. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- ^ a b "True, the output gap is an elusive concept that should never have become a gauge for conducting public policy, and it may be larger than thought.", Monetary policy: lifting the veil of effectivenes, Speech by Benoit Cœuré, 18 December 2019

- ^ Orphanides, Athanasios and Simon van Norden (2002) '"The unreliability of output gap estimates in real time"', Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(4), November 2002, pp. 569–583

- ^ Lipsey, Richard G.; Chrystal, Alec (2007). Economics (Eleventh ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 423. ISBN 9780199286416.

- ^ "February 2013 Baseline Economic Forecast". Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ "Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ Brad DeLong; Lawrence Summers. "Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ "The Employment Situation—September 2013" (PDF). Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ Josh Bivens; Kathryn Edwards. "Cheaper Than You Think: Why Smart Efforts to Spur Jobs Cost Less Than Advertised" (PDF). Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ "The campaign against 'nonsense' output gaps | Bruegel". Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ 2019, May, Robin Brooks, Jonathan Fortun Campaign against nonsense output gaps, Institute of International Finance

- ^ "Output gap nonsense – Adam Tooze". Social Europe. 2019-04-30. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ Buti, Marco; Carnot, Nicolas; Hristov, Atanas; Morrow, Kieran Mc; Roeger, Werner; Vandermeulen, Valerie (2019-09-23). "Potential output and EU fiscal surveillance". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ Darvas, Zsolt. "Why structural balances should be scrapped from EU fiscal rules | Bruegel". Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ ""Output Gap Nonsense" and the EU's Fiscal Rules". Institute for New Economic Thinking. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

External links

- Recurring Reports | Congressional Budget Office - Budget and Economic Outlook and Updates include US real potential GDP.

- 100*(Real Gross Domestic Product-Real Potential Gross Domestic Product)/Real Potential Gross Domestic Product | FRED | St. Louis Fed - US GDP gap