Farrukhsiyar

| Farrukhsiyar | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

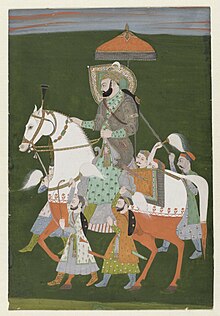

Emperor Farrukhsiyar holding a jewel c. 1717 | |||||||||

| Emperor of Hindustan | |||||||||

| Reign | 11 January 1713 – 28 February 1719 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Jahāndār Shāh | ||||||||

| Successor | Rafī-ud-Darajāt | ||||||||

| Born | 20 August 1683 Aurangabad, Ahmadnagar Subah, Mughal Empire | ||||||||

| Died | 9 April 1719 (aged 35) Shahjahanabad, Delhi, Mughal Empire | ||||||||

| Cause of death | Execution by Immurement | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Spouse |

| ||||||||

| Issue |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| House | House of Babur | ||||||||

| Dynasty | Timurid Dynasty | ||||||||

| Father | Azīm-ush-Shān | ||||||||

| Mother | Sahiba Niswan | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (Hanafi) | ||||||||

| Military career | |||||||||

| Battles / wars | |||||||||

| Mughal emperors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Farrukhsiyar (Persian pronunciation: [faɾ.ˈɾux saj.ˈjɑːɾ]; 20 August 1683 – 9 April 1719), also spelled as Farrukh Siyar, was the tenth Mughal Emperor from 1713 to 1719. He rose to the throne after deposing his uncle Jahandar Shah.[1] He was an emperor only in name, with all effective power in the hands of the courtier Sayyid brothers.[2] He was born during the reign of his great-grandfather Aurangzeb, as the son of Azim-ush-Shan (the second son of Emperor Bahadur Shah I) and Sahiba Niswan. Reportedly a handsome man who was easily swayed by his advisers, he was said to lack the ability, knowledge and character to rule independently. He was executed by Maharaja Ajit Singh of Marwar.

Early life

Muhammad Farrukhsiyar was born on 20 August 1683 (9th Ramzan 1094 AH) in the city of Aurangabad on the Deccan plateau, to a Kashmiri mother, Sahiba Niswan.[3] He was the second son of Azim-ush-Shan, the Grand son of emperor Bahadur Shah I and a great grandson of emperor Aurangzeb.

In 1696, Farrukhsiyar accompanied his father on his campaign to Bengal. Aurangzeb recalled Azim-ush-Shan from Bengal in 1707 and instructed Farrukhsiyar to take charge of the province. Farrukhsiyar spent his early years governing Dhaka (in present-day Bangladesh) the capital city of Bengal Subah.[4]

In 1712 Azim-ush-Shan anticipated Bahadur Shah I's death and a struggle for power, and recalled Farrukhsiyar. He was marching past Azimabad (present-day Patna, Bihar, India) when he learned of the Mughal emperor's death. On 21 March, Farrukhsiyar proclaimed his father's accession to the throne, issued coinage in his name and ordered khutba (public prayer).[4] On 6 April, he learned of his father's defeat to an alliance orchestrated by Zulfiqar Khan Nusrat Jung between Jahandar Shah, and his younger brothers Rafi-us-Shan and Jahan Shah. Although the prince considered suicide, he was dissuaded by his friends from Bengal.[5]

Deposing Jahandar Shah

In 1712, Jahandar Shah (Farrukhsiyar's uncle) ascended the throne of the Mughal Empire by defeating Farrukhsiyar's father, Azim-ush-Shan. Farrukhsiyar wanted revenge for his father's death and was joined by Hussain Ali Khan (the subahdar of Bengal) and Abdullah Khan, his brother and the subahdar of Allahabad.[6]

When they reached Allahabad from Azimabad, Jahandar Shah's military general Syed Abdul Ghaffar Khan Gardezi and 12,000 troops clashed with Abdullah Khan, resulting in Abdullah retreating to the Allahabad Fort. However, Gardezi's army fled when they learned about his death. After the defeat, Jahandar Shah sent general Khwaja Ahsan Khan and his son Aazuddin. When they reached Khajwah (present-day Fatehpur district, Uttar Pradesh, India), they learned that Farrukhsiyar was accompanied by Hussain Ali Khan and Abdullah Khan. With Abdullah Khan commanding the vanguard, Farrukhsiyar began the attack. After a night-long artillery fight, Aazuddin and Khwaja Ahsan Khan fled and the camp fell to Farrukhsiyar.[6]

On 10 January 1713, Farrukhsiyar and Jahandar Shah's forces met at Samugarh, 14 kilometres (9 mi) east of Agra in present-day Uttar Pradesh. Jahandar Shah was defeated and imprisoned, and the following day Farrukhsiyar proclaimed himself the Mughal emperor.[7] On 12 February, Farrukhsiyar marched to the Mughal capital of Delhi, capturing the Red Fort and the citadel. Jahandar Shah's head, mounted on a bamboo rod, was carried by an executioner on an elephant and his body was carried by another elephant.[8]

Reign

Hostility towards the Sayyid Brothers

Farrukhsiyar defeated Jahandar Shah with the aid of the Sayyid brothers, and one of the brothers, Abdullah Khan, wanted the post of wazir (prime minister). His demand was rejected, since the post was promised to Ghaziuddin Khan, but Farrukhsiyar offered him a post as regent under the name of wakil-e-mutlaq. Abdullah Khan refused, saying that he deserved the post of wazir since he led Farrukhsiyar's army against Jahandar Shah. Farrukhsiyar ultimately gave in to his demand, and Abdullah Khan became wazir.[9] His brother Hussain Ali Khan became the Mir Bakhshi or Commander-in-Chief.

According to historian William Irvine, Farrukhsiyar's close aides Mir Jumla III and Khan Dauran sowed seeds of suspicion in his mind that they might usurp him from the throne. Learning about these developments, the other Sayyid brother (Hussain Ali Khan) wrote to Abdullah Khan: "It was clear, from the Prince's talk and the nature of his acts, that he was a man who paid no regard to claims for service performed, one void of faith, a breaker of his word and altogether without shame".[10] Hussain Ali Khan felt it necessary to act in their interests "without regard to the plans of the new sovereign".[11] Farrukhsiyar could not confront them, as the Sayyid Brothers maintained control of the strongest part of the army, and thus the latter became de facto rulers of the empire.[12]

Campaign against Ajmer

Maharaja Ajit Singh of Marwar captured Ajmer with the support of the Marwari nobles and expelled Mughal diplomats from his state. Farrukhsiyar sent Hussain Ali Khan to subjugate him. However, the anti-Sayyid brothers faction in the Mughal emperor's court compelled him to send secret letters to Ajit Singh assuring him of rewards if he defeated Hussain Ali Khan.[13] Hussain Ali Khan left Delhi for Ajmer on 6 January 1714, accompanied by Sarbuland Khan and Afrasyab Khan. As his army reached Sarai Sahal, Ajit Singh sent diplomats who failed to negotiate a peace. As Hussain Ali Khan advanced to Ajmer via Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Merta, Ajit Singh retreated to the deserts hoping to dissuade the Mughal general from a battle. Ajit Singh surrendered at Merta.[14] As a result, Mughal authority was restored in Rajputana. Ajit Singh gave his second daughter, Kunwari Indira Kanwar, as a bride to Farrukhsiyar.[15] His son, Kunwar Abhai Singh, was compelled to accompany him to see the Mughal emperor his brother-in-law.[16]

Campaign against the Jats

Due to Aurangzeb's 25-year campaign on the Deccan plateau, Mughal authority weakened in North India with the rise of local rulers. Taking advantage of the situation, the Jats advanced.[17] In early 1713, Farrukhsiyar unsuccessfully sent subahdar of Agra, Chabela Ram to defeat the Jat leader Churaman. However, his successor, Samsamud Daulah Khan, compelled Churaman to negotiate with the Mughal emperor. Raja Bahadur Rathore accompanied him to the Mughal court, where negotiations with Farrukhsiyar failed.[18]

In September 1716 Raja Jai Singh II undertook a campaign against Churaman, who lived in Thun (in present-day Rajasthan, India). By 19 November, Jai Singh II began besieging the Thun fort.[19] In December Churaman's son, Muhkam Singh, marched from the fort and battled Jai Singh II; the Raja claimed victory. With the Mughals running out of ammunition, Syed Muzaffar Khan was ordered to bring gunpowder, rockets and mounds of lead from the arsenal at Agra.[20]

By January 1718, the siege had lasted for more than a year. With rain coming late in 1717, prices of commodities increased and Raja Jai Singh II found it difficult to continue the siege. He wrote to Farrukhsiyar for reinforcement, saying that he had overcome "many encounters" with the Jats. This failed to impress Farrukhsiyar, so Jai Singh II (via his agent in Delhi) informed Hussain Ali Khan that he would give three million rupees to the government and two million rupees to the minister if he championed his cause to the emperor. With negotiations between Hussain Ali Khan and Farrukhsiyar successful, he accepted his demands and dispatched Syed Khan Jahan to bring Churaman to the Mughal court. Farrukhsiyar issued a farman (royal decree) to Raja Jai Singh II, thanking him for the siege.[21]

On 19 April 1718, Churaman was presented to Farrukhsiyar; they negotiated for peace, with Churaman accepting Mughal authority. Khan Jahan was given the title of Bahadur ("brave"). It was decided that Churaman would pay five million rupees in cash and goods to Farrukhsiyar via Syed Abdullah.[22]

Campaign against the Sikhs

Banda Singh Bahadur was a Sikh leader who, by early 1710s, had captured parts of the Punjab region.[23] Mughal emperors Bahadur Shah I and Jahandar Shah failed to suppress Banda's uprising.[24]

In 1714, the Sirhind faujdar (garrison commander) Zainuddin Ahmad Khan attacked the Sikhs near Ropar. In 1715, Farrukhisyar sent 20,000 troops under Qamaruddin Khan, Abdus Samad Khan and Zakariya Khan Bahadur to defeat Bahadur.[23] After an eight-month siege at Gurdaspur, Banda Singh Bahadur surrendered after he ran out of ammunition. Banda Singh Bahadur and his 200 companions were arrested and brought to Delhi; he was paraded around the city of Sirhind.[25]

Banda Singh Bahadur was put into an iron cage and the remaining Sikhs were chained.[26] They were pressured to give up their faith and become Muslims.[27] Although the emperor promised to spare the Sikhs who converted to Islam, according to William Irvine "not one prisoner proved false to his faith". On their firm refusal all were ordered to be executed.[28] The Sikhs were brought to Delhi in a procession with the 780 Sikh prisoners, 2,000 Sikh heads hung on spears, and 700 cartloads of heads of slaughtered Sikhs used to terrorise the population.[29][30] When Farrukhsiyar's army reached the Red Fort, the Mughal emperor ordered Banda Singh Bahadur, Baj Singh, Fateh Singh and their companions to be imprisoned in Tripolia.[31] After three months of confinement,[32] on 19 June 1716 Farrukhsiyar had Banda Singh Bahadur and his followers executed, despite the wealthy Khatris of Delhi offering money for his release.[33] Banda Singh Bahadur's eyes were gouged out, his limbs were severed, his skin removed, and then he was killed.[34]

Campaign against rebels at the Indus River

Shah Inayat was the leader of poor peasants of Sindh who led a decisive movement against zamindars of Sindh and redistributed land among poor peasants and tillers. He was executed on the order of Emperor Farrukhsiyar in the early eighteenth century.[35]

Re-Imposition of Jizyah

Farrukhsiyar gave power to a number of Kashmiri nobles such as Inayatullah Kashmiri, an old Alamgiri noble, and Muhammad Murad Kashmiri, who he was related to by marriage. This was because he needed a close party of supporters who were directly related to him in dealing with the Sayyid brothers.[36][37][38][3] Inayatullah Khan was appointed the Diwan-i-Tan-o Khalisa, and the governor of Kashmir in 1717. He set fire to the Hindu area of Srinagar and forbade the Pandits from wearing turbans.[39] Inayatullah Khan was further responsible for the re-imposition of Jizyah in the Mughal Empire after the death of Aurangzeb. Farrukhsiyar said to the Hindus:[40]

"Inayatullah has placed before me a letter from the Sherif of Mecca urging that the collection of jizya is obligatory according to our Holy book. In a matter of faith, I am powerless to interfere."

Trade concession in Bengal

In 1717, Farrukhsiyar issued a farman giving the British East India Company the right to reside and trade in the Mughal Empire. They were allowed to trade freely, except for a yearly payment of 3,000 rupees, in gratitude for William Hamilton, a surgeon associated with the company, curing Farrukhsiyar of a disease.[41] The company was given the right to issue dastak (passes) for the movement of goods, which was misused by company officials for personal gain.[42] The farman allowed the British East India company to carry out duty-free trade in the province of Bengal. They were given dastaks (passes), which were misused by the employees of the Company. The dastaks were used for their own private trade, angering the Nawab of Bengal, Alivardi Khan.

Final struggle with the Sayyid Brothers

By 1715, Farrukhsiyar had given Mir Jumla III the power to sign documents on his behalf: "The word and seal of Mir Jumla are my word and seal". Mir Jumla III began approving proposals for jagirs and mansabs without consulting Syed Abdullah, the prime minister.[43] Syed Abdullah's deputy Ratan Chand accepted bribes for him to do work and was involved in revenue farming, which was forbidden by the Mughal emperor. Taking advantage of the situation, Mir Jumla III told Farrukhsiyar that the Sayyids were unfit to hold office and accused them of insubordination. Hoping to depose the brothers, Farrukhsiyar began making military preparations and increased the number of soldiers under Mir Jumla III and Khan Dauran.[44]

After Syed Hussain learned about Farrukhsiyar's plans, he felt that their position could be cemented by controlling "important provinces". He asked to be appointed viceroy of the Deccan, instead of Asaf Jah I; Farrukhsiyar refused, transferring him to the Deccan instead. Fearing attack by Farrukhsiyar's supporters, the brothers began making military preparations. Although Farrukhsiyar initially considered giving the task of crushing the brothers to Mohammad Amin Khan (who wanted the position of prime minister in return), he decided against it because removing him would be difficult.[45]

Arriving at the Deccan, Syed Hussain made a treaty with Maratha ruler Shahu I in February 1718. Shahu was allowed to collect sardeshmukhi in Deccan, and received the lands of Berar and Gondwana to govern. In return, Shahu agreed to pay one million rupees annually and maintain an army of 15,000 horses for the Sayyids. This agreement was reached without Farrukhsiyar's approval,[46] and he was angry when he learned about it: "It was not proper for the vile enemy to be overbearing partners in matters of revenue and government."[47]

State of the Mughal Empire

Appointments

Farrukhsiyar appointed Sayid Abdullah Khan as chief minister and placed Muhammad Baqir Mutamid Khan in charge of the Exchequer. The title of bakshi was first conferred on Hussain Ali Khan (with the titles of Umdat-ul-Mulk, Amir-ul-umara and Bahadur Firuz Jung) and then to Chin Qilich Khan and Afrasayab Khan Bahadur.[48]

The following were governors of the provinces; the governor of South India was Chin Qilich Khan, who appointed deputy governors:[49][50][51]

| North India | South India | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Governor/Chief Minister | Province | Deputy governor |

| Agra | Shams ud Daula Shah Khan-i Dauran | Berar | Iwaz Khan |

| Ajmer | Syed Muzaffar Khan Barha | Bidar | Amin Khan |

| Allahabad | Khan Jahan Barha | Bijapur | Mansur Khan |

| Awadh | Sarbuland Khan | Khandesh | Shukrullah Khan |

| Bengal | Farkhunda Bakht | Hyderabad | Yusuf Khan |

| Bihar | Sayyid Hussain Ali Khan Barha | Carnatic | Saadatullah Khan Nawayath |

| Delhi | Muhammad Yar Khan | ||

| Gujarat | Shahamat Khan | ||

| Kabul | Bahadur Nasir Jang | ||

| Kashmir | Saadat Khan | ||

| Lahore | Abd al-Samad Khan | ||

| Malwa | Raja Jai Singh of Amber | ||

| Multan | Qutb-ul-Mulk Barha | ||

| Orissa | Murshid Quli Khan | ||

Personal life

Family

Farrukhsiyar's first wife was Fakhr-Un-Nissa Begum, also known as Gauhar-Un-Nissa, the daughter of Mir Muhammad Taqi (known as Hasan Khan and then Sadat Khan). Taqi, from the Persian province of Mazandaran, married the daughter of Masum Khan Safawi; if she was the mother of Fakhr-un-nissa, this would account for her daughter's selection as the prince's wife.[52]

His second wife was Bai Indira Kanwar, the daughter of Maharajah Ajit Singh. [53] She married Farrukhsiyar on 27 September 1715, during the fourth year of his reign, and they had no children. After Farrukhsiyar's deposition and death she left the imperial harem on 16 July 1719, she returned to her father with her property and lived her remaining years in Jodhpur.[54]

Farrukhsiyar's third wife was Bai Bhup Devi, daughter of Jaya Singh (the Raja of Kishtwar, who had converted to Islam and received the name of Bakhtiyar Khan). After Jaya Singh's death he was succeeded by his son, Kirat Singh. In 1717, in response to a message from the Mufti of Delhi, her brother Kirat Singh sent her to Delhi with her brother Mian Muhammad Khan. Farrukhsiyar married her, and she entered the imperial harem on 3 July 1717.[54][55]

Titles

His full name was Abul Muzaffer Muinuddin Muhammad Farrukhsiyar Badshah.[56]

Posthumously, he was known as "Shahid-i-marhum" (the martyr received with mercy).[57]

Coinage

On coins issued during Farrukhsiyar's reign, the following phrase was inscribed: "Sikka zad az fazl-i-Haq bar sim o zar/ Padshah-i-bahr-o-bar Farrukhsiyar" (By the grace of the true God, struck on silver and gold, the emperor of land and sea, Farrukhsiyar).[57] There are 116 coins from his reign on display at the Lahore Museum and the Indian Museum in Kolkata. The coins were minted in Kabul, Kashmir, Ajmer, Allahabad, Bidar and Berar.[57]

Deposition and death

With the help of Ajit Singh and Marathas, Farrukhsiyar was blinded, imprisoned and then executed by the Sayyid Brothers in 1719.[58][59] Upon his death, Ajit Singh reclaimed his widowed daughter along with dowry and returned to Jodhpur.[60]

Legacy

The town of Farrukhnagar in Gurgaon district, 32 kilometres (20 mi) south of Delhi, was named for him. During his reign, he built a Sheesh Mahal (palace) and a Jama Masjid (mosque) there.

The town of Farrukhabad in Uttar Pradesh was also named after him.

References

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 193. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

- ^ Sanjay Subrahmanyam (2017). Europe's India. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674977556.

- ^ a b Journal and Proceedings Volume 73, Parts 1-3. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. 1907. p. 306.

- ^ a b Irvine 2006, p. 198.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 199.

- ^ a b Asiatic Society of Bengal 2009, p. 273.

- ^ Asiatic Society of Bengal 2009, p. 274.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 255.

- ^ Tazkirat ul-Mulk by Yahya Khan p.122

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 282.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 283.

- ^ Michael Fischer (2015). A Short History of the Mughal Empire. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 9780857727770.

- ^ The Cambridge Shorter history of India p.456

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 288–290.

- ^ Fisher, p. 78.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 290.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 322.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 323.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 324.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 325.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 326.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 327.

- ^ a b "Marathas and the English Company 1707–1800". San Beck. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ Richards 1995, p. 258.

- ^ Singha, p. 15.

- ^ Duggal, Kartar (2001). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Last to Lay Arms. Abhinav Publications. p. 41. ISBN 9788170174103.

- ^ Singh, Gurbaksh (1927). The Khalsa Generals. Canadian Sikh Study & Teaching Society. p. 12. ISBN 0969409249.

- ^ Jawandha, Nahar (2010). Glimpses of Sikhism. Sanbun Publishers. p. 89. ISBN 9789380213255.

- ^ Johar, Surinder (1987). Guru Gobind Singh. The University of Michigan: Enkay Publishers. p. 208. ISBN 9788185148045.

- ^ Sastri, Kallidaikurichi (1978). A Comprehensive History of India: 1712–1772. The University of Michigan: Orient Longmans. p. 245.

- ^ Singha, p. 16.

- ^ Singh, Ganda (1935). Life of Banda Singh Bahadur: Based on Contemporary and Original Records. Sikh History Research Department. p. 229.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 319.

- ^ Singh, Kulwant (2006). Sri Gur Panth Prakash: Episodes 1 to 81. Institute of Sikh Studies. p. 415. ISBN 9788185815282.

- ^ Ansari, Sarah F. D. (1992). Sufi saints and state power : the pirs of Sind, 1843-1947. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40530-0. OCLC 23694258.

- ^ G. S. Cheema (2002). The Forgotten Mughals:A History of the Later Emperors of the House of Babar, 1707-1857. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 142. ISBN 9788173044168.

- ^ A Study of Eighteenth Century India: Political history, 1707-1761. Saraswat Library. 1976.

- ^ Jagadish Narayan Sarkar (1976). A Study of Eighteenth Century India: Political history, 1707-1761. Saraswat Library.

- ^ Victoria Schofield (1996). Kashmir in Conflict:India, Pakistan and the Unending War. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 23. ISBN 9781860640360.

- ^ R.K. Gupta, S.R. Bakshi (2008). Rajasthan Through the Ages. Sarup & Sons. p. 174. ISBN 9788176258418.

- ^ Samaren Roy (May 2005). Calcutta: Society and Change 1690–1990. iUniverse. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-595-34230-3.

- ^ Vipul Singh, Jasmine Dhillon, Gita Shanmugavel. History and Civics. Pearson India. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-317-6320-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chandra 2007, p. 476.

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 477.

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 478.

- ^ Ram Sivasankaran (22 December 2015). The Peshwa: The Lion and the Stallion. Westland. p. 5. ISBN 978-93-85724-70-1.

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 481.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 258.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 261.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 262.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 263.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 400-1.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 400.

- ^ a b Irvine 2006, p. 401.

- ^ Proceedings – Punjab History Conference – Volumes 29-30. Punjabi University. 1998. p. 85.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 398.

- ^ a b c Irvine 2006, p. 399.

- ^ Irvine 2006, p. 390.

- ^ Kenneth Pletcher (April 2010). The History of India. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 978-1615302017.

- ^ Melia Belli Bose (2015). Royal Umbrellas of Stone: Memory, Politics, and Public Identity in Rajput Funerary Art. Brill. p. 176. ISBN 9789004300569.

Bibliography

- Asiatic Society of Bengal (18 August 2009). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 47. Bishop's College Press.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Chandra, Satish (July 2007), Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughal Empire, Har Anand Publications Pvt Ltd., ISBN 978-81-241-1269-4

- Irvine, William (2006), The Later Mughals, Low Price Publications, ISBN 81-7536-406-8

- Fisher, Michael H. (1 October 2015), A Short History of the Mughal Empire, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-0-85772-976-7

- Richards, John F. (1995), The New Cambridge History of India: Part I, Volume V - The Mughal Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521566032

- Singha, H.S. (1 January 2005), Sikh Studies, Book 6, Hemkunt Press, ISBN 978-81-7010-258-8