Spain under Joseph Bonaparte

Kingdom of the Spains and the Indies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1808–1813 | |||||||||

| Motto: Plus Ultra (Latin) "Further Beyond" | |||||||||

| Anthem: Marcha Real (Spanish) "Royal March" | |||||||||

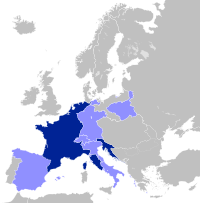

Spanish territory controlled at some point during the war by King Joseph Bonaparte. Military governments dependent on Paris (since 1810): Biscay, Navarre and Aragon Military government of Catalonia, dependent on Paris (since 1810) / Territory annexed to the French Empire (since 1812). Territory never controlled by Joseph Bonaparte's government, besides Spanish America: Canary Islands, Cadiz, Ceuta, Melilla, Cartagena, Alicante and Balearic Islands. | |||||||||

| Status | Client state of the French Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Madrid | ||||||||

| Official languages | French (dynastic) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism (State Religion) | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Spaniard, Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary semi-constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1808–1813 | Joseph I | ||||||||

| Regent | |||||||||

• 1808 | Joachim Murat | ||||||||

| First Secretary of State | |||||||||

• 1808–1813 | Mariano Luis de Urquijo | ||||||||

• 1813 | Juan O'Donoju O'Ryan | ||||||||

• 1813 | Fernando de Laserna | ||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Generales | ||||||||

| Historical era | Napoleonic Wars | ||||||||

| 6 May 1808 | |||||||||

| 8 July 1808 | |||||||||

| 21 June 1813 | |||||||||

| 11 December 1813 | |||||||||

| Currency | Spanish real | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Spain | ||||||||

| History of Spain |

|---|

18th century map of Iberia |

| Timeline |

Napoleonic Spain was the part of Spain loyal to Joseph I during the Peninsular War (1808–1813), forming a Bonapartist client state officially known as the Kingdom of the Spains and the Indies after the country was partially occupied by the French Imperial Army of the First French Empire.

The Napoleonic government was opposed by various regions remaining loyal to Ferdinand VII of the old Bourbon kingdom, which formed a series of Juntas allied with the Coalition forces of Britain and Portugal. Fighting across the Iberian Peninsula would be largely inconclusive until a series of Coalition victories from 1812 to 1813 at Salamanca and Vitoria meant the defeat of the Bonapartist régime and the expulsion of Napoleon I's troops. The Treaty of Valençay recognized Ferdinand VII as the legitimate King of Spain.[1]

Background: From alliance with First French Republic and First French Empire to the Peninsular War

The abdications of Ferdinand VII and Charles IV

Spain had been allied with France against Britain since the Second Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1796. After the defeat of the combined Spanish and French fleets by the British at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, cracks began to appear in the alliance, with Spain preparing to invade France from the south after the outbreak of the War of the Fourth Coalition. In 1806, Spain readied for an invasion in case of a Prussian victory, but Napoleon I's rout of the Prussian Army at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt caused Spain to back down. However, Spain continued to resent the loss of its fleet at Trafalgar and the fact that it was forced to join the Continental System. Nevertheless, the two allies agreed to partition Portugal, a long-standing British trading partner and ally, which refused to join the Continental System.

Napoleon was fully aware of the disastrous state of Spain's economy and administration, and its political fragility. He came to believe that it had little value as an ally in the current circumstances. He insisted on positioning French troops in Spain to prepare for an invasion of Portugal, but once this was done, he continued to move additional French troops into Spain without any sign of an advance into Portugal. The presence of French troops on Spanish soil was extremely unpopular in Spain, resulting in the Tumult of Aranjuez by supporters of Ferdinand VII, the heir apparent to the throne. Charles IV of Spain abdicated in March 1808 and his prime minister, Manuel de Godoy was also ousted.

Ferdinand VII was declared the legitimate monarch, and returned to Madrid expecting to take up his duties as king. Napoleon Bonaparte summoned Ferdinand VII to Bayonne, France, and he went, fully expecting Napoleon Bonaparte to approve his position as monarch. Napoleon I had also summoned Charles IV, who arrived separately. Napoleon I pressed Ferdinand VII to abdicate in favor of his father, who had abdicated under duress. Charles IV then abdicated in favor of Napoleon I, since he did not want his despised son to be heir to the throne. Napoleon I placed his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the throne. The formal abdications were designed to preserve the legitimacy of the new sitting monarch.

The installation of Joseph Bonaparte

Charles IV hoped that Napoleon I, who by this time had 100,000 troops stationed in Spain, would help him regain the throne. However, Napoleon I refused to help Charles IV, and also refused to recognize his son - Ferdinand VII, as the new king. Instead, he succeeded in pressuring both Charles IV and Ferdinand VII to cede the crown to his brother, Joseph Bonaparte. The head of the French forces in Spain, Marshal Joachim Murat, meanwhile pressed for the former Prime Minister of Spain, Manuel de Godoy, whose role in inviting the French forces into Spain had led to the mutiny of Aranjuez, to be set free. The failure of the remaining Spanish government to stand up to Murat caused popular anger. On 2 May 1808, the younger son of Charles IV, the Infante Francisco de Paula, left Spain for France, leading to a widespread rebellion in the streets of Madrid.

The Council of Castile, the main organ of central government in Spain under Charles IV, was now in Napoleon's control. However, due to the popular anger at French rule, it quickly lost authority outside the population centers which were directly French-occupied. To oppose this occupation, former regional governing institutions, such as the Cortes of Aragon and the Board of the Principality of Asturias, resurfaced in parts of Spain; elsewhere, juntas (councils) were created to fill the power vacuum and lead the struggle against French imperial forces. Provincial juntas began to coordinate their actions; regional juntas were formed to oversee the provincial ones. Finally, on 25 September 1808, a single Supreme Central Junta was established in Aranjuez to serve as the acting resistance government for all of Spain.

The French occupation

Joachim Murat established a plan of conquest, sending two large armies to attack pockets of pro-Ferdinand resistance. One army secured the route between Madrid and Vitoria and besieged Zaragoza, Girona, and Valencia. The other, sent south to Andalusia, sacked Córdoba. Instead of proceeding to Cádiz as planned, General Dupont was ordered to march back to Madrid, but was defeated by General Castaños at the Battle of Bailén on 22 July 1808. This victory encouraged the resistance against the French in several countries elsewhere in Europe. After the battle, King Joseph left Madrid to take refuge in Vitoria. In the fall of 1808, Napoleon himself entered Spain, entering Madrid on 2 December and returning Joseph I to the capital. Meanwhile, a British army entered Spain from Portugal but was forced to retreat to Galicia. In early 1810, the Napoleonic offensive reached the vicinity of Lisbon, but were unable to penetrate the fortified Lines of Torres Vedras.

Reign of Joseph I

The Josephine State had its legal basis in the Bayonne Statute.

When Ferdinand VII left Bayonne, in May 1808, he asked that all institutions co-operate with the French authorities. On 15 June 1808 Joseph Bonaparte, the elder brother of Napoleon I was made King. The Council of Castile assembled in Bayonne, though only 65 of the total 150 members attended. The Assembly ratified the transfer of the Crown to Joseph Bonaparte and adopted with little change apart from a constitutional text drafted by Napoleon I. Most of those assembled did not perceive any contradiction between patriotism and collaboration with the new king. Moreover, it was not the first time a foreign dynasty had assumed the Spanish Crown: at the start of the eighteenth century, the House of Bourbon came to Spain from France after the last of the Spanish Habsburgs, Charles II, died without offspring.

Napoleon Bonaparte and Joseph Bonaparte both underestimated the level of opposition that the appointment would create. Having successfully appointed Joseph I King of Naples in 1806 and other family rulers in Holland in 1806 and Westphalia in 1807, it came as a surprise to have created a political and later military disaster.[2]

Joseph Bonaparte promulgated the Bayonne Statute on 7 July 1808. As a constitutional text, it is a royal charter, because it was not the result of a sovereign act of the nation assembled in Parliament, but a royal edict. The text was imbued with a spirit of reform, in line with the Bonaparte ideals, but adapted to the Spanish culture so as to win the support of the elites of the old regime. It recognized the Catholic religion as the official religion and forbade the exercise of other religions. It did not contain an explicit statement about the separation of powers, but asserted the independence of the judiciary. Executive power lay in the King and his ministers. The courts, in the manner of the old regime, were constituted of the estates of the clergy, the nobility and the people. Except with regard to the budget, its ability to make laws was influenced by the power of the monarch. In fact, the King was only forced to call Parliament every three years. It contained no explicit references to legal equality of citizens, although it was implicit in the equality in taxation, the abolition of privileges and equal rights between Spanish and American citizens.[vague] The Constitution also recognized the freedom of industry and trade, the abolition of trade privileges and the elimination of internal customs.

The Constitution established the Cortes Generales, an advisory body composed of the Senate which was formed by the male members of the royal family and 24 members appointed by the king from the nobles and the clergy, and a legislative assembly, with representatives from the estates of the nobility and the clergy. The Constitution established an authoritarian regime that included some enlightened projects, such as the abolition of torture, but preserving the Inquisition.

The Spanish uprising resulted in the Battle of Bailén on 16–19 July 1808, which resulted in a French defeat and Joseph I with the French high command fleeing Madrid and abandoning much of Spain.[2]

During his stay in Vitoria, Joseph Bonaparte had taken important steps to organise the state institutions, including creating an advisory Council of State. The king appointed a government, whose leaders formed an enlightened group which adopted a reform program. The Inquisition was abolished, as was the Council of Castile which was accused of anti-French policy. He decreed the end of feudal rights, the reduction of religious communities and the abolition of internal customs charges.

This period saw measures to liberalize trade and agriculture and the creation of a stock exchange in Madrid. The State Council undertook the division of land into 38 provinces.

As the popular revolt against Joseph I spread, many who had initially co-operated with the House of Bonaparte left their ranks. But there remained numerous Spanish, known as afrancesados, who nurtured his administration and made the Peninsular War partially a civil war. The afrancesados saw themselves as heirs of enlightened absolutism and saw the arrival of Bonaparte as an opportunity to modernize the country. Many had been a part of government in the reign of Charles IV, for example, François Cabarrus, former head of finance and Mariano Luis de Urquijo, Secretary of State from November 1808 to April 1811.[2] But there were also writers like playwright Leandro Fernández de Moratín, scholars like Juan Antonio Llorente, the mathematician Alberto Lista, and musicians such as Fernando Sor.

Throughout the war, Joseph I tried to exercise full authority as the King of Spain, preserving some autonomy against the designs of his brother Napoleon I. In this regard, many afrancesados believed that the only way to maintain national independence was to collaborate with the new dynasty, as the greater the resistance to the French, the greater would be the subordination of Spain to the French Imperial Army and its war requirements. In fact, the opposite was the case: although in the territory controlled by King Joseph I modern rational administration and institutions replaced the Old Regime, the permanent state of war reinforced the power of the French marshals, barely allowing the civil authorities to act.

The military defeats suffered by the French Imperial Army forced Joseph I to leave Madrid on three occasions:

- In July 1808, following the French defeat in the Battle of Bailén, until it was recaptured by the French in November.[2]

- From 12 August until 2 November 1812 whilst the Anglo-Portuguese Army occupied his capital - Madrid.

- Joseph I left Madrid in May 1813 for the last time, and later Spain in June 1813, following the French defeat in Battle of Vitoria, ending the failed stage of enlightened absolutism. Most of Joseph I's supporters (about 10,000 and 12,000) fled to France into exile, along with the retreating French troops after the war, and their property was confiscated. Joseph I abdicated.

Post-abdication

Joseph Bonaparte spent time in France, he commanded the Battle of Paris, then travelling to the United States (where he sold the jewels he had taken from Spain). He lived there from 1817 to 1832,[3] initially in New York City and Philadelphia, where his house became the centre of activity for French expatriates, he married American Ann Savage in Society Hill.

Joseph Bonaparte returned to Europe, where he died in Florence, Tuscany (present day Italy), and was buried in the Les Invalides building complex in Paris, France.[4]

Second government of Spain – Cortes of Cádiz

In 1810, the Cortes of Cádiz was created, it operated as a government in exile. The Cortes Generales had to move from Seville to Cádiz to escape the French advance (The French enforced the Siege of Cádiz from 5 February 1810 to 24 August 1812, and the port city never surrendered). Its members disbanded and transferred its powers to a Council of Regency. The five regents convened the meeting of the Cortes in Cadiz. Cortes were representatives of the estates, but were unable to hold elections either in Spain or in the American colonies. The assembly thus lost its estates in favor of territorial representation.

The Constitution of Cádiz

The Cortes opened their sessions in September 1810 on the Isla de León. They consisted of 97 deputies, 47 of whom were alternates from Cádiz residents, who approved a decree expressing represent the Spanish nation and declared legally constituted in general and special courts in which lay the national sovereignty.[5]

The constitution they wrote did not last long. On 24 March 1814, six weeks after returning to Spain, Ferdinand VII abolished the constitution and had all monuments to it torn down.

The Allied victory

In March 1813, threatened by the Anglo-Spanish army, Joseph I had left the capital and the Coalition offensive intensified and culminated in the Battle of Vitoria in June. French troops were finally evicted from Spain following the conclusion of the Siege of San Sebastián in September 1813, so removing any possibility of a return. In December 1813, the Treaty of Valençay provided for the restoration of Ferdinand VII.

See also

- History of Spain

- Peninsular War

- Chronology of events of the Peninsular War

- Napoleonic Wars

- Afrancesados

References

- ^ José Luis Comellas (1988). Historia de España Contemporánea. Ediciones Rialp. ISBN 978-84-321-2441-9. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d "King Joseph Iís Government in Spain and its Empire". napoleon-series.org.

- ^ "Joseph Bonaparte at Point Breeze". Flat Rock. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ Kwoh, Leslie (10 June 2007). "Yes, a Bonaparte feasted here". Star Ledger. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ "Spain - THE LIBERAL ASCENDANCY - The Cadiz Cortes". countrystudies.us.