Free State of Brunswick

| Free State of Brunswick Freistaat Braunschweig (German) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State of Germany | |||||||||||

| 1918–1946 | |||||||||||

The Free State of Brunswick within the Weimar Republic | |||||||||||

Territory of Brunswick (shown here with the post-World War II inner German border between East and West Germany) | |||||||||||

| Capital | Brunswick (Braunschweig) | ||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||

| • Type | Republic (de facto until 1933) National Socialist one-party totalitarian dictatorship (de facto 1933-1945) | ||||||||||

| Council Chairman | |||||||||||

• 1918–1919 | Sepp Oerter | ||||||||||

• 1919–1920 | Heinrich Jasper | ||||||||||

| Minister-President | |||||||||||

• 1919–1920 (first) | Heinrich Jasper | ||||||||||

• 1946 (last) | Alfred Kubel | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Landtag | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||||

• Established | 10 November 1918 | ||||||||||

• Abolition de facto | 14 October 1933 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1 November 1946 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||||||

The Free State of Brunswick (German: Freistaat Braunschweig) was a state of the German Reich in the time of the Weimar Republic. It was formed after the abolition of the Duchy of Brunswick in the course of the German revolution of 1918–1919. Its capital was Braunschweig (Brunswick). In 1933 it was de facto abolished by Nazi Germany. The free state was disestablished after the Second World War in November 1946.

History

The Duchy of Brunswick had been established after the 1814 Congress of Vienna, as a sovereign successor state of the German Confederation.[1] It roughly comprised the incoherent territory of the former Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, stretching from Holzminden on the Weser River in the west to Blankenburg in the Harz mountain range and Calvörde in the east.[2]

The Brunswick territory was largely surrounded by the Prussian provinces of Hanover (the former Kingdom of Hanover) and Saxony.[2] From 1913 it was ruled by Duke Ernest Augustus of the House of Hanover.[3]

Revolution

The reports on the Kiel mutiny of 3 November 1918 sparked unrest in Braunschweig, when local revolutionaries led by the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) stormed the local prison, occupied the railway station and the police headquarters, and also attacked Brunswick Palace. On 8 November Duke Ernest Augustus of Brunswick was forced to abdicate and went into exile.[4][5] Two days later, a workers' council proclaimed the "Socialist Republic of Brunswick", ruled by a council of USPD revolutionaries.

However, their intentions to implement a Soviet republic failed, as in the first parliamentary elections on 22 December 1918 the USPD officials were outnumbered by the Social Democrats (SPD), who reached 27.7% of the votes cast.[6] On 22 February 1919, both parties formed a coalition government led by the USPD politician Joseph ("Sepp") Oerter,[7] that shifted the state's constitution towards a parliamentary republic. However, the government had to deal with subsequent uprisings in the capital Braunschweig, led by the Communist Spartacus League, which on 9 April called a general strike. Four days later, the Reich government declared the state of emergency in Brunswick and crushed the Spartacist revolt with the aid of invading Freikorps troops under Georg Ludwig Rudolf Maercker.[8][9]

On 30 April 1919, the Brunswick Landtag legislature elected a new state government under the Social Democratic prime minister Heinrich Jasper, based on a coalition of SPD, USPD and the liberal German Democratic Party (DDP). The Freikorps troops left Braunschweig ten days later, and the Reich government officially lifted emergency rule on 5 June.

Free State

Jasper's government stabilized public policy. However, in the 1920 state election, the SPD suffered a heavy loss of votes and the succeeding coalition government was again led by his USPD rival Sepp Oerter. The Brunswick free state constitution was adopted on 6 January 1922.

In the 1922 elections, the SPD/USPD government finally lost its majority, whereafter the Social Democrats under Heinrich Jasper formed a coalition with the DDP and the national liberal German People's Party (DVP). At the same time, the rising Nazi Party (NSDAP) established first local branches in Braunschweig and Wolfenbüttel, until it was banned by the state government on 13 September 1923. Nevertheless, the party was represented in the Brunswick Landtag, when Sepp Oerter switched from left to right and joined the NSDAP in 1924.

After the 1924 elections, the DVP led a right-wing coalition government of several national liberal and conservative parties, among them the National Socialist Freedom Movement (NSFB), a substitute of the outlawed Nazi Party. The Social Democrats under Heinrich Jasper once again were able to form a government upon the 1927 elections, however, it lost its majority in the following elections of 1930. The NSDAP reached 22.9% of the votes cast, whereafter the Nazi politician Anton Franzen joined the new right-wing government as Minister of the Interior,[10] succeeded by his party fellow Dietrich Klagges on 15 September 1931.

Klagges was instrumental for the dismissal of opposition public servants and in organizing the anti-democratic Harzburg Front in October 1931. He is especially known for naturalizing the former Austrian citizen Adolf Hitler, who had been stateless for seven years and aimed to run in the 1932 German presidential election.[11] After the failure of a first attempt to obtain him a tenure at Braunschweig University of Technology, Minister Klagges finally managed to appoint Hitler as a public functionary at the Brunswick delegation to the Reichsrat in Berlin in 1932, which gave him citizenship of Brunswick, and thus automatically of Germany.[12] There are no records of any activity by Hitler in this (high-paid) position. After his appointment as Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933, he was officially dismissed.

Before and after the Nazi Machtergreifung, Communist and SPD politicians were persecuted and arrested in Brunswick.[13] As part of the Gleichschaltung (coordination) process, the "Provisional Law on the Coordination of the States with the Reich" was enacted on 30 March 1933. This dissolved all the sitting Landtage and reconstituted them on the basis of the recent 5 March 1933 Reichstag election results, which had given the Nazi Party and its coalition partner the DNVP a working majority. Klagges was elected Minister-president of Brunswick on 6 May, and together with his party colleagues Justice Minister Friedrich Alpers and Chief of Police Friedrich Jeckeln, he established a terror regime. He nevertheless found himself superseded by Reichsstatthalter (Reich Governor) Wilhelm Friedrich Loeper, whose office had been established on 7 April by the "Second Law on the Coordination of the States with the Reich." The last Landtag session was held on 13 June 1933, it was dissolved on 14 October and no new elections were scheduled. On 30 January 1934, the "Law on the Reconstruction of the Reich" formally abolished all the Landtage and transferred the sovereignty of the states to the central government.

Allied occupation

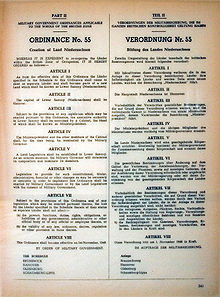

On 12 April 1945, US forces took the city of Brunswick and deposed the Nazi government. The Brunswick territory became part of the British occupation zone, with the exception of the eastern Blankenburg and Calvörde areas, which fell to Soviet-administered Saxony-Anhalt. On 7 May 1946, the British authorities appointed the Social Democratic politician Alfred Kubel minister-president, the last before the Brunswick territory within the British zone merged with the State of Hanover (the former Prussian province), the Free States of Oldenburg and Schaumburg-Lippe into the newly founded state (Land) of Lower Saxony, effective on 1 November 1946.[14]

The Brunswick region remained a Lower Saxon Verwaltungsbezirk (from 1978: Regierungsbezirk) until its dissolution in 2004. The Brunswick state constitution of 1922 was not repealed until a 2011 resolution by the Landtag of Lower Saxony.

Leaders

Chairmen of the Council of People's Commissioners, 1918–1919

- 1918–1919: Sepp Oerter (USPD)

- 1919–1920: Heinrich Jasper (SPD)

Ministers-President, 1919–1946

- 1919–1920: Heinrich Jasper (SPD)

- 1920–1921: Sepp Oerter (USPD)

- 1921–1922: August Junke (SPD)

- 1922: Otto Antrick (SPD)

- 1922: Heinrich Jasper (SPD)

- 1924–1927: Gerhard Marquordt (DVP)

- 1927–1930: Heinrich Jasper (SPD)

- 1930–1933: Werner Küchenthal (DNVP)

- 1933–1945: Dietrich Klagges (NSDAP)

- 1945–1946: Hubert Schlebusch (SPD)

- 1946: Alfred Kubel (SPD)

Reichsstatthalter

Reichsstatthalter for Anhalt and Brunswick (headquarters in Dessau)

- 1933–1935: Wilhelm Loeper

- 1935–1937: Fritz Sauckel

- 1937–1945: Rudolf Jordan

Administration

The Free State of Brunswick initially comprised the City of Braunschweig and the following rural districts:

- Blankenburg (divided in 1945 between British and Soviet zone of occupation)

- Braunschweig

- Gandersheim

- Holzminden (to the Prussian province of Hanover on 1 November 1941 in return for the District of Goslar and the City of Goslar)

- Helmstedt

- Wolfenbüttel

On 1 April 1942 the city district of Watenstedt-Salzgitter was established on Goslar and Wolfenbüttel territory.

Bibliography

- Reinhard Bein: Braunschweig zwischen rechts und links. Der Freistaat 1918 bis 1930. Döring, Braunschweig 1990, ISBN 3-925268-05-7.

- Reinhard Bein: Im deutschen Land marschieren wir. Freistaat Braunschweig 1930–1945. 6th edition. Döring, Braunschweig 1992, ISBN 3-925268-02-2.

- Horst-Rüdiger Jarck, Gerhard Schildt (eds.): Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region. 2nd edition. Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2001, ISBN 3-930292-28-9.

- Helmut Kramer (ed.): Braunschweig unterm Hakenkreuz. Magni Buchladen, Braunschweig 1981, ISBN 3-922571-03-4.

- Jörg Leuschner, Karl Heinrich Kaufhold, Claudia Märtl (eds.): Die Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte des Braunschweigischen Landes vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. 3 vols. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 2008, ISBN 978-3-487-13599-1.

- Richard Moderhack (ed.): Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte im Überblick. 3rd edition, Braunschweigischer Geschichtsverein, Braunschweig 1979.

- Werner Pöls, Klaus Erich Pollmann (eds.): Moderne Braunschweigische Geschichte. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 1982, ISBN 3-487-07316-1.

- Hans Reinowski: Terror in Braunschweig – Aus dem 1. Quartal der Hitlerherrschaft. Zurich 1933.

- Ernst-August Roloff: Braunschweig und der Staat von Weimar. Waisenhaus-Buchdruckerei und Verlag, Braunschweig 1964.

- Ernst-August Roloff: Bürgertum und Nationalsozialismus 1930–1933. Braunschweigs Weg ins Dritte Reich. Hanover 1961.

- Ehm Welk: Im Morgennebel. 2nd edition, Verlag Volk und Welt, East Berlin 1954 (novel).

See also

References

- ^ Gerhard Schildt: Von der Restauration zur Reichsgründungszeit, in Horst-Rüdiger Jarck / Gerhard Schildt (eds.), Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region, Braunschweig 2000, pp. 751–753

- ^ a b Wolfgang Meibeyer: Die Landesnatur. Territorium - Lage - Grenzen, in Horst-Rüdiger Jarck / Gerhard Schildt (eds.), Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region, Braunschweig 2000, p. 23

- ^ Klaus Erich Pollmann (2000): Das Herzogtum im Kaiserreich (1871–1914), in Horst-Rüdiger Jarck / Gerhard Schildt (eds.), Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region, Braunschweig 2000, pp. 821–830

- ^ Moderhack, Richard (1997). Braunschweiger Stadtgeschichte (in German). Braunschweig: Wagner. pp. 193–194. ISBN 3-87884-050-0.

- ^ Rother, Bernd (1990). Die Sozialdemokratie im Land Braunschweig 1918 bis 1933 (in German). Bonn: Verlag J. H. W. Dietz Nachf. pp. 27–30. ISBN 3-8012-4016-9.

- ^ Rother 1990, pp. 36–37

- ^ Rother 1990, pp. 288

- ^ Rother 1990, pp. 67–72

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Ludewig (2000): Der Erste Weltkrieg und die Revolution (1914–1918/19), in: Horst-Rüdiger Jarck / Gerhard Schildt (eds.), Die Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. Jahrtausendrückblick einer Region, Braunschweig 2000, pp. 935–943

- ^ Rother 1990, p. 234

- ^ Rother 1990, p. 247

- ^ Hajo Holborn (1 December 1982). 1840-1945. Princeton University Press. pp. 689–. ISBN 978-0-691-00797-7.

- ^ Rother 1990, pp. 247–248

- ^ "Lower Saxony". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2 November 2015.