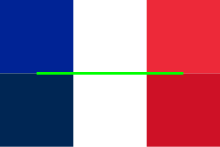

Flag of France

| |

| Tricolore | |

| Use | National flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 (habitual) |

| Adopted | 15 February 1794 (darker variant on 13 July 2020)[a] |

| Design | A vertical tricolour of blue, white, and red |

| Designed by | Jacques-Louis David |

| |

| Use | National flag |

| Proportion | 2:3 (habitual) |

| Adopted | 1976[1] |

| Design | An interchangeable variant of the national flag with lighter shades |

The national flag of France (drapeau national de la France) is a tricolour featuring three vertical bands coloured blue (hoist side), white, and red. The design was adopted after the French Revolution, whose revolutionaries were influenced by the horizontally striped red-white-blue flag of the Netherlands.[2][3] While not the first tricolour, it became one of the most influential flags in history. The tricolour scheme was later adopted by many other nations in Europe and elsewhere, and, according to the Encyclopædia Britannica has historically stood "in symbolic opposition to the autocratic and clericalist royal standards of the past".

Before the tricolour was adopted the royal government used many flags, the best known being a blue shield and gold fleurs-de-lis (the Royal Arms of France) on a white background, or state flag. Early in the French Revolution, the Paris militia, which played a prominent role in the storming of the Bastille, wore a cockade of blue and red,[4] the city's traditional colours. According to French general Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, white was the "ancient French colour" and was added to the militia cockade to form a tricolour, or national, cockade of France.[5]

This cockade became part of the uniform of the National Guard, which succeeded the militia and was commanded by Lafayette.[6] The colours and design of the cockade are the basis of the Tricolour flag, adopted in 1790,[7] originally with the red nearest to the flagpole and the blue farthest from it. A modified design by Jacques-Louis David was adopted in 1794. The royal white flag was used during the Bourbon Restoration from 1815 to 1830; the tricolour was brought back after the July Revolution and has been used since then, except for an interruption for a few days in 1848.[8] Since 1976, there have been two versions of the flag in varying levels of use by the state: the original (identifiable by its use of navy blue) and one with a lighter shade of blue. Since July 2020, France has used the older variant by default, including at the Élysée Palace.[9][10]

Design

Article 2 of the French constitution of 1958 states that "the national emblem is the tricolour flag, blue, white, red".[11] No law has specified the shades of these official colours.[12][13] In English blazon, the flag is described as tierced in pale azure, argent and gules.

The blue stripe has usually been a dark navy blue; a lighter blue (and lighter red) version was introduced in 1976[1] by President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing.[10][13] Both versions were used from then; town halls, public buildings and barracks usually fly the darker version of the flag, but the lighter version was sometimes used even on official State buildings.[9]

On 13 July 2020, President Emmanuel Macron reverted,[9] without any statement and with no orders for other institutions to use a specific version, to the darker hue for the presidential Élysée Palace, as a symbol of the French Revolution.[14] The move was met with comments both in favour of and against the change, but it was noted that both the darker and lighter flags have been in use for decades.[10]

| Authority | Scheme | Blue | White | Red |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Defense[15][16] | AFNOR NFX 08002 |

A 503 | A 665 | An 805 |

| Embassy to Germany (lighter colours)[17] |

Pantone | Reflex blue | Safe | Red 032 |

| CMYK | 100.80.0.0 | 0.0.0.0 | 0.100.100.0 | |

| RGB | (0,85,164) | (255,255,255) | (239,65,53) | |

| HEX | #0055A4 | #FFFFFF | #EF4135 |

Currently, the flag is one and a half times wider than its height (i.e. in the proportion 2:3) and, except in the French Navy, has stripes of equal width. Initially, the three stripes of the flag were not equally wide, being in the proportions 30 (blue), 33 (white) and 37 (red). Under Napoleon I, the proportions were changed to make the stripes' width equal, but by a regulation dated 17 May 1853, the navy went back to using the 30:33:37 proportions, which it now continues to use, as the flapping of the flag makes portions farther from the halyard seem smaller.

When the French president or prime minister is expected to be photographed at an official or televised event, a flag with a much narrower white stripe is often used as a backdrop to ensure that all three stripes are visible when the cameras are focused on them, as using a flag with equal stripes might show only the white stripe in frame.[18][19]

Symbolism

Blue and red are the traditional colours of Paris, used on the city's coat of arms. Blue is identified with Saint Martin, red with Saint Denis.[20] At the storming of the Bastille in 1789, the Paris militia wore blue and red cockades on their hats. White had long featured prominently on French flags and is described as the "ancient French colour" by Lafayette.[5] White was added to the "revolutionary" colours of the militia cockade to "nationalise" the design, thus forming the cockade of France.[5] Although Lafayette identified the white stripe with the nation, other accounts identify it with the monarchy.[21] Lafayette denied that the flag contains any reference to the red-and-white livery of the Duc d'Orléans. Despite this, Orléanists adopted the tricolour as their own.

Blue and red are associated with the Virgin Mary, the patroness of France, and were the colours of the oriflamme. The colours of the French flag may also represent the three main estates of the Ancien Régime (the clergy: white, the nobility: red and the bourgeoisie: blue). Blue, as the symbol of class, comes first and red, representing the nobility, comes last. Both extreme colours are situated on each side of white referring to a superior order.[22]

The cockade of France was adopted in July 1789, a moment of national unity that soon faded. Royalists began wearing white cockades and flying white flags, while the Jacobins, and later the Socialists, flew the red flag. The tricolour, which combines royalist white with republican red, came to be seen as a symbol of moderation and of a nationalism that transcended factionalism.

The French government website states that the white field was the colour of the king, while blue and red were the colours of Paris.

The three colours are occasionally taken to represent the three elements of the revolutionary motto, liberté (freedom: blue), égalité (equality: white), fraternité (brotherhood: red); this symbolism was referenced in Krzysztof Kieślowski's three colours film trilogy, for example.

In the aftermath of the November 2015 Paris attacks, many famous landmarks and stadiums around the world were illuminated in the flag colours to honour the victims.

History

Kingdom of France

During the early Middle Ages, the oriflamme, the flag of Saint Denis, was used—red, with two, three, or five spikes. Originally, it was the royal banner under the Capetians. It was stored in Saint-Denis abbey, where it was taken when war broke out. French kings went forth into battle preceded either by Saint Martin's red cape, which was supposed to protect the monarch, or by the red banner of Saint Denis.

Later during the Middle Ages, these colours came to be associated with the reigning house of France. In 1328, the coat-of-arms of the House of Valois was blue with gold fleurs-de-lis bordered in red. From this time on, the kings of France were represented in vignettes and manuscripts wearing a red gown under a blue coat decorated with gold fleurs-de-lis. Charles V of France changed the design from an all-over scattering of fleurs-de-lis to a group of three in about 1376; these two coats are known in heraldic terminology as France Ancient and France Modern, respectively.

During the Hundred Years' War, England was recognised by a red cross; Burgundy, a red saltire; and France, a white cross. This cross could figure either on a blue or a red field. The blue field eventually became the common standard for French armies. The French regiments were later assigned the white cross as standard, with their proper colours in the cantons. The French flag of a white cross on a blue field is still seen on some flags derived from it, such as that of Quebec.

The flag of Joan of Arc during the Hundred Years' War is described in her own words, "I had a banner of which the field was sprinkled with lilies; the world was painted there, with an angel at each side; it was white of the white cloth called 'boccassin'; there was written above it, I believe, 'JHESUS MARIA'; it was fringed with silk."[23] Joan's standard led to the prominent use of white on later French flags.[23]

From the accession of the Bourbons to the throne of France, the green ensign of the navy became a plain white flag, the symbol of purity and royal authority. The merchant navy was assigned "the old flag of the nation of France", the white cross on a blue field.[24] There also was a red jack for the French galleys. A variant of the plain white Bourbon banner, a white field strewn with gold fleur de lis, was also sometimes seen.

- The Oriflamme, the banner of the Capetians

The Royal Banner of France[25] or "Bourbon Flag". The House of Bourbon ruled France from 1589 to 1792 and again from 1815 to 1848.

The Royal Banner of France[25] or "Bourbon Flag". The House of Bourbon ruled France from 1589 to 1792 and again from 1815 to 1848.

The Tricolore

The horizontally striped red-white-blue flag of the Netherlands originally inspired the colour scheme used by the French revolutionaries after the French Revolution in 1789.[2][3] Consequently, the French tricolour flag is derived from the cockade of France used during the French Revolution. These were circular rosette-like emblems attached to the hat. Camille Desmoulins asked his followers to wear green cockades on 12 July 1789. The Paris militia, formed on 13 July, adopted a blue and red cockade. Blue and red are the traditional colours of Paris, and they are used on the city's coat of arms. The addition of white has been attributed to Lafayette, Mayor Jean Sylvain Bailly, and even Louis XVI himself.[26] This episode is supposed to have taken place on July 17, 1789, on the occasion of the king's visit to the Paris city hall. However, it is proven that the tricolor cockade began to be worn, by order of the city, from the 13th or 14th of July.[27] In any case, Louis XVI actually went to the Paris city hall where he received the tricolor cockade. On 27 July, a tricolour cockade was adopted as part of the uniform of the National Guard, the national police force that succeeded the militia.[28]

A drapeau tricolore with vertical red, white and blue stripes was approved by the Constituent Assembly on 24 October 1790. Simplified designs were used to illustrate how the revolution had broken with the past. The order was reversed to blue-white-red, the current design, by a resolution passed on 15 February 1794.

When the Bourbon dynasty was restored following the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the tricolore—with its revolutionary connotations—was replaced by a white flag, the pre-revolutionary naval flag. However, following the July Revolution of 1830, the "citizen-king", Louis-Philippe, restored the tricolore, and it has remained France's national flag since that time.

Following the overthrow of Napoleon III, voters elected a royalist majority to the National Assembly of the new Third Republic. This parliament then offered the throne to the Bourbon pretender, Henri, Comte de Chambord. However, he insisted that he would accept the throne only on the condition that the tricolour be replaced by the white flag.[29] As the tricolour had become a cherished national symbol, this demand proved impossible to accommodate. Plans to restore the monarchy were adjourned and ultimately dropped, and France has remained a republic, with the tricolour flag, ever since.

The Vichy régime, which dropped the word "republic" in favour of "the French state", maintained the use of the tricolore, but Philippe Pétain used as his personal standard a version of the flag with, in the white stripe, an axe made with a star-studded marshal's baton. This axe is called the "Francisque" in reference to the ancient Frankish throwing axe. During this same period, the Free French Forces used a tricolore with, in the white stripe, a red Cross of Lorraine.

The constitutions of 1946 and 1958 instituted the "blue, white, and red" flag as the national emblem of the Republic.

The colours of the national flag are occasionally said to represent different flowers; blue represents cornflowers, white represents marguerites, and red represents poppies.[30]

- The flag of Paris, source of the tricolour's blue and red stripes

- The cockade of France, designed in July 1789. White was added to "nationalise" an earlier blue and red design.

- The flag of France used from 1794 (interrupted in 1815–1830 and in 1848)

The French Second Republic adopted a variant of the tricolour for a few days between 24 February and 5 March 1848.[8]

The French Second Republic adopted a variant of the tricolour for a few days between 24 February and 5 March 1848.[8] The French tricolore with the royal crown and fleur-de-lys was possibly designed by the Henri, Count of Chambord, in his younger years as a compromise, but which was never made official, and which he himself rejected when offered the throne in 1870.[31]

The French tricolore with the royal crown and fleur-de-lys was possibly designed by the Henri, Count of Chambord, in his younger years as a compromise, but which was never made official, and which he himself rejected when offered the throne in 1870.[31]- From 1912 onwards, the French Air Force originated the use of roundels on military aircraft shortly before World War I. Similar national cockades, with different ordering of colours, were later adopted as aircraft roundels by their allies.[32]

Flag used by the Free French Forces during World War II; in the centre is the Cross of Lorraine; later, the personal standard of President Charles de Gaulle, as Chief of the Free France.

Flag used by the Free French Forces during World War II; in the centre is the Cross of Lorraine; later, the personal standard of President Charles de Gaulle, as Chief of the Free France.- The flag of France, darker red and blue variant.

- The flag of France, lighter red and blue variant.

Regimental flags

- The French soldiers started to use white crosses, during the Hundred Years' War, to distinguish themselves from the English soldiers wearing red crosses.

- A white-crossed regimental flag during the Ancien Régime (here, Régiment d'Auvergne)

- La Sarre Regiment (Régiment de la Sarre)

- King's Regiment (Régiment du Roi)

- Queen's Regiment (Régiment de la Reine)

- General Lévis' Regiment Flag in North America. Now official flag of the city of Lévis, Quebec

- The pre-revolutionary regimental flags inspired the flag of Quebec (here, the Compagnies Franches de la Marine).

- Regimental flag of the 1st Regiment of Grenadiers of the French Imperial Guard (1812)

- Current regimental flags of the 1st and 2nd Regiments of the Légion étrangère

Naval flags

Colonial flags

Most French colonies either used the regular tricolour or a regional flag without the French flag. There were some exceptions:

Flag of Laos in French Indochina

Flag of Laos in French Indochina Flag of the Sip Song Chau Tai, French Indochina (1948–1955)

Flag of the Sip Song Chau Tai, French Indochina (1948–1955) Flag of Gabon (1959–1960)

Flag of Gabon (1959–1960) Flag of Madagascar under French protection (1885–1895)

Flag of Madagascar under French protection (1885–1895) Merchant flag of the French protectorate of Morocco (1912–1956)

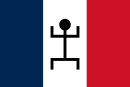

Merchant flag of the French protectorate of Morocco (1912–1956) Flag used by some military units based in the French protectorate of Tunisia

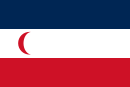

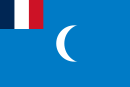

Flag used by some military units based in the French protectorate of Tunisia Briefly used flag of the French Mandate of Syria and the Lebanon in 1920

Briefly used flag of the French Mandate of Syria and the Lebanon in 1920 Flag of the State of Aleppo, in the French Mandate of Syria (1920–1924)

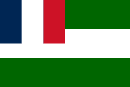

Flag of the State of Aleppo, in the French Mandate of Syria (1920–1924) Flag of the State of Damascus, in the French Mandate of Syria (1920–1924)

Flag of the State of Damascus, in the French Mandate of Syria (1920–1924) Flag of the State of Syria, in the French Mandate of Syria (1924–1930)

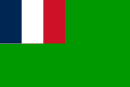

Flag of the State of Syria, in the French Mandate of Syria (1924–1930) Flag of the State of Alawites, in the French Mandate of Syria

Flag of the State of Alawites, in the French Mandate of Syria Flag of Jabal ad-Druze, in the French Mandate of Syria

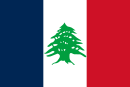

Flag of Jabal ad-Druze, in the French Mandate of Syria Flag of the State of Greater Lebanon during the French mandate 1920–1943

Flag of the State of Greater Lebanon during the French mandate 1920–1943 Flag of Republic of Independent Guyana (1886–1887)

Flag of Republic of Independent Guyana (1886–1887) Flag of the French Protectorate of Wallis and Futuna (Uvea) (1860–1886)

Flag of the French Protectorate of Wallis and Futuna (Uvea) (1860–1886) Present unofficial flag of Wallis and Futuna

Present unofficial flag of Wallis and Futuna Flag of the Kingdom of Tahiti under the Protectorate of France (1845–1880)

Flag of the Kingdom of Tahiti under the Protectorate of France (1845–1880) Flag of the French protectorate of Rurutu in French Polynesia (1858–1889)

Flag of the French protectorate of Rurutu in French Polynesia (1858–1889) Flag of French Polynesia

Flag of French Polynesia Flag of the French protectorate of Saar (1947–1956)

Flag of the French protectorate of Saar (1947–1956)- Flag of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands

Other

Many provinces and territories in Canada have French-speaking communities with flags represents:

- The Acadian flag used in Canada is based on the tricolour flag of France, but this flag was never used during French rule of Acadia. It was adopted in 1884. Acadians live mainly in Louisiana, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia.

- The current flag of Quebec. The use of blue and white is a characteristic of pre-revolutionary flags.

- Flag of Franco-Newfoundlanders

- Proposed flag of the French Congo (pre-1959)

Many areas in North America have substantial French-speaking and ancestral communities:

- Flag of Acadiana

- Flag of United Franco-Americans

- Flag of New England Franco-Americans

- Flag of Aroostook county Franco-Americans

- Flag of Androscoggin county Franco-Americans

- Flag of Illinois Country Franco-Americans

- Flag of Iowa

- Flag of New Orleans, Louisiana

- Flag of Mobile, Alabama

New Hebrides used several flags incorporating both the British Union Flag and the French flag.

- Flag attested as being used in the 1963 South Pacific Games[33]

- Dark blue version attested at the time of the 1969 South Pacific Games[34]

In the Shanghai International Settlement, the flag of Shanghai Municipal Council has a shield incorporating the French tricolour.

- Flag of the Shanghai Municipal Council, Shanghai International Settlement

Two territories of Vietnam used flags based on the tricolour flag of France.

- Montagnard country (1946–1950)

- Tai Autonomous Territory (1946–1950)

Gallery

- French regimental flag, Paris, autochrome dated 1917

- Flag of France, color photography dated 1930

- Multiple French flags as commonly flown from public buildings

See also

- List of French flags

- Flags of the regions of France

- National emblem of France

- Armorial of France

- Cockade of France

- Flag of Somoto, Nicaragua, similar design

- Flag of Haiti (based on French Republican flag)

Notes

- ^ Use has not been continuous: readopted in 1830 after a 15 year gap, last re-adopted on 5 March 1848 after a few days.

References

- ^ a b "À propos du bleu du drapeau tricolore -" [About the blue of the tricolour flag]. Société Française de Vexillologie (in French). n.d. Archived from the original on 15 October 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ a b Eriksen, Thomas Hylland; Jenkins, Richard, eds. (2007). Flag, nation and symbolism in Europe and America. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-93496-8. OCLC 182759362.

- ^ a b "Flags That Look Alike | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Presa della Bastiglia, il 14 luglio e il rosso della first lady messicana Angelica" (in Italian). 14 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert Du Motier Lafayette (marquis de), Memoirs, correspondence and manuscripts of General Lafayette, vol. 2, p. 252.

- ^ Gaines, James (September 2015). "Washington & Lafayette". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Curiat, Andrea (3 March 2011). "La storia del tricolore". Il Sole 24 ORE (in Italian). Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Les couleurs du drapeau de 1848". Revue d'Histoire du Xixe Siècle - 1848. 28 (139): 237–238. 1931. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ a b c de Raguenel, Louis (14 November 2021). "Emmanuel Macron a changé la couleur du drapeau français" [Emmanuel Macron has changed the colour of the French flag]. Europe 1 (in French). Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

La décision de changer la couleur du drapeau français a été prise par le président de la République le 13 juillet 2020 (…)

- ^ a b c "Macron switches to using navy blue on France's flag - reports". BBC News. 14 November 2021. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Article 2". Constitution du 4 octobre 1958 (in French). Légifrance (French government). Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Discrètement, Emmanuel Macron a changé la tonalité du drapeau bleu-blanc-rouge" [Emmanuel Macron has discreetly changed the hue of the blue-white-red flag]. RMC (in French). 15 November 2021. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

La Constitution ne précise pas la tonalité des couleurs. Aucune loi non plus.

- ^ a b "Drapeau Français". promo-drapeaux.fr. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021.

- ^ Osborne, Samuel (15 November 2021). "Emmanuel Macron changed colour of French flag in 'very political' decision". Sky News. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

But they also said the "very political" decision was made "to revive a symbol of the French Revolution".

- ^ Couleurs de la défense nationale [Colours for the French ministry of defence] (PDF) (Technical report) (in French). République Française - Ministére de la Défense. March 2009. NORMDEF 0001, Édition 01.

- ^ "Die Symbole der französischen Republik". Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ de Boutiny, Arthur (18 November 2016). "Dix choses que vous ignoriez sûrement sur les drapeaux" [Ten things you surely don't know about flags]. L'Obs website (in French). Archived from the original on 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Drapeau français à bande blanche étroite" [The French flag with a narrow white stripe] (in French). Drapeaux-SFV (former information blog of the French Society of Vexillology). 2010–2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "The three colours before the flag". Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Le drapeau français" [The French flag]. Élysée (France) (in French). n.d. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012.

- ^ "The French flag - Colours of the flag". users.skynet.be/lotus/flag/fra0-en.htm. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b Whitney Smith, Flags through the ages and across the world, McGraw-Hill, England, 1975 ISBN 0-07-059093-1, pp. 66–67, The Standard of Joan of Arc, after quoting her from her trial transcript he states: "it was her influence which determined that white should serve as the principal French national colour from shortly after her death in 1431 until the French Revolution almost 350 years later."

- ^

- "...the standard of France was white, sprinkled with golden fleur de lis..." (Ripley & Dana 1879, p. 250).

- On the reverse of this plate it says: "Le pavillon royal était véritablement le drapeau national au dix-huitième siecle...Vue du chateau d'arrière d'un vaisseau de guerre de haut rang portant le pavillon royal (blanc, avec les armes de France)" (Vinkhuijzen collection 2011).

- "The oriflamme and the Chape de St Martin were succeeded at the end of the 16th century, when Henry III., the last of the house of Valois, came to the throne, by the white standard powdered with fleurs-de-lis. This in turn gave place to the famous tricolour"(Chisholm 1911, p. 460).

- ^ The Governor General of Canada (12 November 2020). "Royal Banner of France – Heritage Emblem". Confirmation of the blazon of a Flag. February 15, 2008 Vol. V, p. 202. The Office of the Secretary to the Governor General. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Pinoteau, Hervé (1992). "Les trois couleurs en 1789". Bulletin de la Société nationale des Antiquaires de France. 1990 (1): 42–44. doi:10.3406/bsnaf.1992.9536. Archived from the original on 2 March 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Cocarde tricolore ; les origines du drapeau français". www.contreculture.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Clifford, Dale, "Can the Uniform Make the Citizen? Paris, 1789–1791", Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2001, p. 369.

- ^ Martin, Jacques (2022) [23 March 1978]. "The Humour of Pope Pius IX". L'Osservatore Romano (English weekly ed.). Baltimore, MD: The Cathedral Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2022 – via EWTN Global Catholic Network.

- ^ "Côte-d'Or - Histoire. Cuisine de guerre : coquelicot et bleuet". www.bienpublic.com (in French). Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Whitney Smith. Flags through the ages and cross the world. McGraw-Hill Book Company. 1975. p. 75.

- ^ Royal Air Force Museum Archived 2 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Historical Flags (Vanuatu)". Flags of the World. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ "postage stamp New Hebrides Condominium 1F featuring 3rd South Pacific Games Port Moresby 1969 dated 1969". Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

Sources

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 454–463.

Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). "Flag". The American Cyclopædia. Vol. 8. p. 250.

Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). "Flag". The American Cyclopædia. Vol. 8. p. 250.- "The Vinkhuijzen collection of military uniforms: France, 1750–1757". New York Public Library. 25 March 2011 [2004]. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015.

Further reading

- Flags Through the Ages and Across the World, Smith, Whitney, McGraw-Hill Book Co. Ltd, England, 1975. ISBN 0-07-059093-1.

External links

- France at Flags of the World

- French flag at Flags Corner Archived 24 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine

![The Royal Banner of France[25] or "Bourbon Flag". The House of Bourbon ruled France from 1589 to 1792 and again from 1815 to 1848.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Royal_flag_of_France.svg/130px-Royal_flag_of_France.svg.png)

![The French Second Republic adopted a variant of the tricolour for a few days between 24 February and 5 March 1848.[8]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Drapeau_france_1848.svg/130px-Drapeau_france_1848.svg.png)

![The French tricolore with the royal crown and fleur-de-lys was possibly designed by the Henri, Count of Chambord, in his younger years as a compromise, but which was never made official, and which he himself rejected when offered the throne in 1870.[31]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d4/Henri_d%27Artois%27_Flag_of_France_%28proposed%29.svg/130px-Henri_d%27Artois%27_Flag_of_France_%28proposed%29.svg.png)

![From 1912 onwards, the French Air Force originated the use of roundels on military aircraft shortly before World War I. Similar national cockades, with different ordering of colours, were later adopted as aircraft roundels by their allies.[32]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/Roundel_of_France.svg/120px-Roundel_of_France.svg.png)

![Flag attested as being used in the 1963 South Pacific Games[33]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cd/Flag_Vanuatu_1963.svg/130px-Flag_Vanuatu_1963.svg.png)

![Flag attested as being used in the 1966 and 1971 South Pacific Games[33]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3d/Flag_of_New_Hebrides.svg/130px-Flag_of_New_Hebrides.svg.png)

![Dark blue version attested at the time of the 1969 South Pacific Games[34]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Flag_of_New_Hebrides_%281969%29.svg/130px-Flag_of_New_Hebrides_%281969%29.svg.png)