Fern

| Ferns Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Polypodiophyta |

| Class: | Polypodiopsida Cronquist, Takht. & W.Zimm. |

| Subclasses[2] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The ferns (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta) are a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. They differ from mosses by being vascular, i.e., having specialized tissues that conduct water and nutrients, and in having life cycles in which the branched sporophyte is the dominant phase.[3]

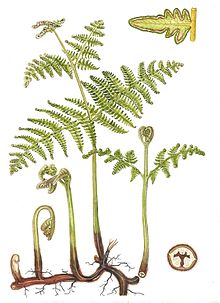

Ferns have complex leaves called megaphylls that are more complex than the microphylls of clubmosses. Most ferns are leptosporangiate ferns. They produce coiled fiddleheads that uncoil and expand into fronds. The group includes about 10,560 known extant species. Ferns are defined here in the broad sense, being all of the Polypodiopsida, comprising both the leptosporangiate (Polypodiidae) and eusporangiate ferns, the latter group including horsetails, whisk ferns, marattioid ferns, and ophioglossoid ferns.

The fern crown group, consisting of the leptosporangiates and eusporangiates, is estimated to have originated in the late Silurian period 423.2 million years ago,[4] but Polypodiales, the group that makes up 80% of living fern diversity, did not appear and diversify until the Cretaceous, contemporaneous with the rise of flowering plants that came to dominate the world's flora.

Ferns are not of major economic importance, but some are used for food, medicine, as biofertilizer, as ornamental plants, and for remediating contaminated soil. They have been the subject of research for their ability to remove some chemical pollutants from the atmosphere. Some fern species, such as bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) and water fern (Azolla filiculoides), are significant weeds worldwide. Some fern genera, such as Azolla, can fix nitrogen and make a significant input to the nitrogen nutrition of rice paddies. They also play certain roles in folklore.

Description

Sporophyte

Extant ferns are herbaceous perennials and most lack woody growth.[5] When woody growth is present, it is found in the stem.[6] Their foliage may be deciduous or evergreen,[7] and some are semi-evergreen depending on the climate.[8] Like the sporophytes of seed plants, those of ferns consist of stems, leaves and roots. Ferns differ from spermatophytes in that they reproduce by spores rather than having flowers and producing seeds.[6] However, they also differ from spore-producing bryophytes in that, like seed plants, they are polysporangiophytes, their sporophytes branching and producing many sporangia. Also unlike bryophytes, fern sporophytes are free-living and only briefly dependent on the maternal gametophyte.

The green, photosynthetic part of the plant is technically a megaphyll and in ferns, it is often called a frond. New leaves typically expand by the unrolling of a tight spiral called a crozier or fiddlehead into fronds.[9] This uncurling of the leaf is termed circinate vernation. Leaves are divided into two types: sporophylls and tropophylls. Sporophylls produce spores; tropophylls do not. Fern spores are borne in sporangia which are usually clustered to form sori. The sporangia may be covered with a protective coating called an indusium. The arrangement of the sporangia is important in classification.[6]

In monomorphic ferns, the fertile and sterile leaves look morphologically the same, and both are able to photosynthesize. In hemidimorphic ferns, just a portion of the fertile leaf is different from the sterile leaves. In dimorphic (holomorphic) ferns, the two types of leaves are morphologically distinct.[10] The fertile leaves are much narrower than the sterile leaves, and may have no green tissue at all, as in the Blechnaceae and Lomariopsidaceae.

The anatomy of fern leaves can be anywhere from simple to highly divided, or even indeterminate (e.g. Gleicheniaceae, Lygodiaceae). The divided forms are pinnate, where the leaf segments are completely separated from one other, or pinnatifid (partially pinnate), where the leaf segments are still partially connected. When the fronds are branched more than once, it can also be a combination of the pinnatifid are pinnate shapes. If the leaf blades are divided twice, the plant has bipinnate fronds, and tripinnate fronds if they branch three times, and all the way to tetra- and pentapinnate fronds.[11][12] In tree ferns, the main stalk that connects the leaf to the stem (known as the stipe), often has multiple leaflets. The leafy structures that grow from the stipe are known as pinnae and are often again divided into smaller pinnules.[13]

Fern stems are often loosely called rhizomes, even though they grow underground only in some of the species. Epiphytic species and many of the terrestrial ones have above-ground creeping stolons (e.g., Polypodiaceae), and many groups have above-ground erect semi-woody trunks (e.g., Cyatheaceae, the scaly tree ferns). These can reach up to 20 meters (66 ft) tall in a few species (e.g., Cyathea brownii on Norfolk Island and Cyathea medullaris in New Zealand).[14]

Roots are underground non-photosynthetic structures that take up water and nutrients from soil. They are always fibrous and are structurally very similar to the roots of seed plants.

Gametophyte

As in all vascular plants, the sporophyte is the dominant phase or generation in the life cycle. The gametophytes of ferns, however, are very different from those of seed plants. They are free-living and resemble liverworts, whereas those of seed plants develop within the spore wall and are dependent on the parent sporophyte for their nutrition. A fern gametophyte typically consists of:[3]

- Prothallus: A green, photosynthetic structure that is one cell thick, usually heart or kidney shaped, 3–10 mm long and 2–8 mm broad. The prothallus produces gametes by means of:

- Antheridia: Small spherical structures that produce flagellate antherozoids.[3]

- Archegonia: A flask-shaped structure that produces a single egg at the bottom, reached by the male gametophyte by swimming down the neck.[3]

- Rhizoids: root-like structures (not true roots) that consist of single greatly elongated cells, that absorb water and mineral salts over the whole structure. Rhizoids anchor the prothallus to the soil.[3]

Life cycle and Reproduction

The lifecycle of a fern involves two stages, as in club mosses and horsetails. In stage one, the spores are produced by sporophytes in sporangia, which are clustered together in sori (s.g. sorus), developing on the underside of fertile fronds. In stage two, the spores germinate into a short-lived structure anchored to the ground by rhizoids called gametophyte which produce gametes. When a mature fertile frond bears sori, and spores are released, the spores will settle on the soil and send out rhizoids, while it develops into a prothallus. The prothallus bears spherical antheridia (s.g. antheridium) which produce antherozoids (male gametophytes) and archegonia (s.g. archegonium) which release a single oosphere. The antherozoid swims up the archegonium and fertilize the oosphere, resulting in a zygote, which will grow into a separate sporophyte, while the gametophyte shortly persists as a free-living plant.[3]

Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus (1753) originally recognized 15 genera of ferns and fern allies, classifying them in class Cryptogamia in two groups, Filices (e.g. Polypodium) and Musci (mosses).[15][16][17] By 1806 this had increased to 38 genera,[18] and has progressively increased since (see Schuettpelz et al (2018)). Ferns were traditionally classified in the class Filices, and later in a Division of the Plant Kingdom named Pteridophyta or Filicophyta. Pteridophyta is no longer recognised as a valid taxon because it is paraphyletic. The ferns are also referred to as Polypodiophyta or, when treated as a subdivision of Tracheophyta (vascular plants), Polypodiopsida, although this name sometimes only refers to leptosporangiate ferns. Traditionally, all of the spore producing vascular plants were informally denominated the pteridophytes, rendering the term synonymous with ferns and fern allies. This can be confusing because members of the division Pteridophyta were also denominated pteridophytes (sensu stricto).

Traditionally, three discrete groups have been denominated ferns: two groups of eusporangiate ferns, the families Ophioglossaceae (adder's tongues, moonworts, and grape ferns) and Marattiaceae; and the leptosporangiate ferns. The Marattiaceae are a primitive group of tropical ferns with large, fleshy rhizomes and are now thought to be a sibling taxon to the leptosporangiate ferns. Several other groups of species were considered fern allies: the clubmosses, spikemosses, and quillworts in Lycopodiophyta; the whisk ferns of Psilotaceae; and the horsetails of Equisetaceae. Since this grouping is polyphyletic, the term fern allies should be abandoned, except in a historical context.[19] More recent genetic studies demonstrated that the Lycopodiophyta are more distantly related to other vascular plants, having radiated evolutionarily at the base of the vascular plant clade, while both the whisk ferns and horsetails are as closely related to leptosporangiate ferns as the ophioglossoid ferns and Marattiaceae. In fact, the whisk ferns and ophioglossoid ferns are demonstrably a clade, and the horsetails and Marattiaceae are arguably another clade.

Molecular phylogenetics

Smith et al. (2006) carried out the first higher-level pteridophyte classification published in the molecular phylogenetic era, and considered the ferns as monilophytes, as follows:[20]

- Division Tracheophyta (tracheophytes) - vascular plants

- Sub division Euphyllophytina (euphyllophytes)

- Infradivision Moniliformopses (monilophytes)

- Infradivision Spermatophyta - seed plants, ~260,000 species

- Subdivision Lycopodiophyta (lycophytes) - less than 1% of extant vascular plants

- Sub division Euphyllophytina (euphyllophytes)

Molecular data, which remain poorly constrained for many parts of the plants' phylogeny, have been supplemented by morphological observations supporting the inclusion of Equisetaceae in the ferns, notably relating to the construction of their sperm and peculiarities of their roots.[20]

The leptosporangiate ferns are sometimes called "true ferns".[21] This group includes most plants familiarly known as ferns. Modern research supports older ideas based on morphology that the Osmundaceae diverged early in the evolutionary history of the leptosporangiate ferns; in certain ways this family is intermediate between the eusporangiate ferns and the leptosporangiate ferns. Rai and Graham (2010) broadly supported the primary groups, but queried their relationships, concluding that "at present perhaps the best that can be said about all relationships among the major lineages of monilophytes in current studies is that we do not understand them very well".[22] Grewe et al. (2013) confirmed the inclusion of horsetails within ferns sensu lato, but also suggested that uncertainties remained in their precise placement.[23] Other classifications have raised Ophioglossales to the rank of a fifth class, separating the whisk ferns and ophioglossoid ferns.[23]

Phylogeny

The ferns are related to other groups as shown in the following cladogram:[19][24][25][2]

| Tracheophyta |

| ||||||||||||

| (vascular plants) |

Nomenclature and subdivision

The classification of Smith et al. in 2006 treated ferns as four classes:[20][26]

- Equisetopsida (Sphenopsida) 1 order, Equisetales (Horsetails) ~ 15 species

- Psilotopsida 2 orders (whisk ferns and ophioglossoid ferns) ~92 species

- Marattiopsida 1 order, Marattiales ~ 150 species

- Polypodiopsida (Filicopsida) 7 orders (leptosporangiate ferns) ~ 9,000 species

In addition they defined 11 orders and 37 families.[20] That system was a consensus of a number of studies, and was further refined.[23][27] The phylogenetic relationships are shown in the following cladogram (to the level of orders).[20][28][23] This division into four major clades was then confirmed using morphology alone.[29]

|

Subsequently, Chase and Reveal considered both lycopods and ferns as subclasses of a class Equisetopsida (Embryophyta) encompassing all land plants. This is referred to as Equisetopsida sensu lato to distinguish it from the narrower use to refer to horsetails alone, Equisetopsida sensu stricto. They placed the lycopods into subclass Lycopodiidae and the ferns, keeping the term monilophytes, into five subclasses, Equisetidae, Ophioglossidae, Psilotidae, Marattiidae and Polypodiidae, by dividing Smith's Psilotopsida into its two orders and elevating them to subclass (Ophioglossidae and Psilotidae).[25] Christenhusz et al.[a] (2011) followed this use of subclasses but recombined Smith's Psilotopsida as Ophioglossidae, giving four subclasses of ferns again.[30]

Christenhusz and Chase (2014) developed a new classification of ferns and lycopods. They used the term Polypodiophyta for the ferns, subdivided like Smith et al. into four groups (shown with equivalents in the Smith system), with 21 families, approximately 212 genera and 10,535 species;[19]

- Equisetidae (=Equisetopsida) - monotypic (Equisetales, Equisetaceae, Equisetum) horsetails ~ 20 species)

- Ophioglossidae (=Psilotopsida) - 2 monotypic orders ~ 92 species

- Marattiidae (=Marattiopsida) - 1 monotypic order (Marattiales, Marattiaceae, 2 subfamilies) ~ 130 species

- Polypodiidae (=Polypodiopsida) - 7 orders

This was a considerable reduction in the number of families from the 37 in the system of Smith et al., since the approach was more that of lumping rather than splitting. For instance a number of families were reduced to subfamilies. Subsequently, a consensus group was formed, the Pteridophyte Phylogeny Group (PPG), analogous to the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, publishing their first complete classification in November 2016. They recognise ferns as a class, the Polypodiopsida, with four subclasses as described by Christenhusz and Chase, and which are phylogenetically related as in this cladogram:

| Christenhusz and Chase 2014[2] | Nitta et al. 2022[4] and Fern Tree of life[31] |

|---|---|

In the Pteridophyte Phylogeny Group classification of 2016 (PPG I), the Polypodiopsida consist of four subclasses, 11 orders, 48 families, 319 genera, and an estimated 10,578 species.[32] Thus Polypodiopsida in the broad sense (sensu lato) as used by the PPG (Polypodiopsida sensu PPG I) needs to be distinguished from the narrower usage (sensu stricto) of Smith et al. (Polypodiopsida sensu Smith et al.)[2] Classification of ferns remains unresolved and controversial with competing viewpoints (splitting vs lumping) between the systems of the PPG on the one hand and Christenhusz and Chase on the other, respectively. In 2018, Christenhusz and Chase explicitly argued against recognizing as many genera as PPG I.[17][33]

| Smith et al. (2006)[20] | Chase & Reveal (2009)[25] | Christenhusz et al. (2011)[30] | Christenhusz & Chase (2014, 2018)[19][34] | PPG I (2016)[2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ferns (no rank) |

monilophytes (no rank) |

ferns (monilophytes) (no rank) |

ferns (Polypodiophyta) (no rank) |

Class Polypodiopsida |

| Class Equisetopsida | Subclass Equisetidae | Subclass Equisetidae | Subclass Equisetidae | Subclass Equisetidae |

| Class Psilotopsida | Subclass Ophioglossidae Subclass Psilotidae |

Subclass Ophioglossidae | Subclass Ophioglossidae | Subclass Ophioglossidae |

| Class Marattiopsida | Subclass Marattiidae | Subclass Marattiidae | Subclass Marattiidae | Subclass Marattiidae |

| Class Polypodiopsida | Subclass Polypodiidae | Subclass Polypodiidae | Subclass Polypodiidae | Subclass Polypodiidae |

Evolution and biogeography

Fern-like taxa (Wattieza) first appear in the fossil record in the middle Devonian period, ca. 390 Mya. By the Triassic, the first evidence of ferns related to several modern families appeared. The great fern radiation occurred in the late Cretaceous, when many modern families of ferns first appeared.[35][1][36][37] Ferns evolved to cope with low-light conditions present under the canopy of angiosperms.

Remarkably, the photoreceptor neochrome in the two orders Cyatheales and Polypodiales, integral to their adaptation to low-light conditions, was obtained via horizontal gene transfer from hornworts, a bryophyte lineage.[38]

Due to the very large genome seen in most ferns, it was suspected they might have gone through whole genome duplications, but DNA sequencing has shown that their genome size is caused by the accumulation of mobile DNA like transposons and other genetic elements that infect genomes and get copied over and over again.[39]

Ferns appear to have evolved extrafloral nectaries 135 million years ago, nearly simultaneously with the trait's evolution in angiosperms. However, nectary-associated diversifications in ferns did not hit their stride until nearly 100 million years later, in the Cenozoic. There is weak support for the rise of fern-feeding arthropods driving this diversification.[40]

Distribution and habitat

Ferns are widespread in their distribution, with the greatest richness in the tropics and least in arctic areas. The greatest diversity occurs in tropical rainforests.[41] New Zealand, for which the fern is a symbol, has about 230 species, distributed throughout the country.[42] It is a common plant in European forests.

Ecology

Fern species live in a wide variety of habitats, from remote mountain elevations, to dry desert rock faces, bodies of water or open fields. Ferns in general may be thought of as largely being specialists in marginal habitats, often succeeding in places where various environmental factors limit the success of flowering plants. Some ferns are among the world's most serious weed species, including the bracken fern growing in the Scottish highlands, or the mosquito fern (Azolla) growing in tropical lakes, both species forming large aggressively spreading colonies. There are four particular types of habitats that ferns are found in: moist, shady forests; crevices in rock faces, especially when sheltered from the full sun; acid wetlands including bogs and swamps; and tropical trees, where many species are epiphytes (something like a quarter to a third of all fern species).[43]

Especially the epiphytic ferns have turned out to be hosts of a huge diversity of invertebrates. It is assumed that bird's-nest ferns alone contain up to half the invertebrate biomass within a hectare of rainforest canopy.[44]

Many ferns depend on associations with mycorrhizal fungi. Many ferns grow only within specific pH ranges; for instance, the climbing fern (Lygodium palmatum) of eastern North America will grow only in moist, intensely acid soils, while the bulblet bladder fern (Cystopteris bulbifera), with an overlapping range, is found only on limestone.

The spores are rich in lipids, protein and calories, so some vertebrates eat these. The European woodmouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) has been found to eat the spores of Culcita macrocarpa, and the bullfinch (Pyrrhula murina) and the New Zealand lesser short-tailed bat (Mystacina tuberculata) also eat fern spores.[45]

- In undergrowth below coast redwoods, California

- Fern bed under a forest canopy, Virginia

- On a wall

- Epiphytic ferns in India

Life cycle

Ferns are vascular plants differing from lycophytes by having true leaves (megaphylls), which are often pinnate. They differ from seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) in reproducing by means of spores and lacking flowers and seeds. Like all land plants, they have a life cycle referred to as alternation of generations, characterized by alternating diploid sporophytic and haploid gametophytic phases. The diploid sporophyte has 2n paired chromosomes, where n varies from species to species. The haploid gametophyte has n unpaired chromosomes, i.e. half the number of the sporophyte. The gametophyte of ferns is a free-living organism, whereas the gametophyte of the gymnosperms and angiosperms is dependent on the sporophyte.

The life cycle of a typical fern proceeds as follows:

- A diploid sporophyte phase produces haploid spores by meiosis (a process of cell division which reduces the number of chromosomes by a half).

- A spore grows into a free-living haploid gametophyte by mitosis (a process of cell division which maintains the number of chromosomes). The gametophyte typically consists of a photosynthetic prothallus.

- The gametophyte produces gametes (often both sperm and eggs on the same prothallus) by mitosis.

- A mobile, flagellate sperm fertilizes an egg that remains attached to the prothallus.

- The fertilized egg is now a diploid zygote and grows by mitosis into a diploid sporophyte (the typical fern plant).

Sometimes a gametophyte can give rise to sporophyte traits like roots or sporangia without the rest of the sporophyte.[46]

- Gametophyte (thallus) and sporophyte (ascendant frond) of Onoclea sensibilis

Uses

Ferns are not as important economically as seed plants, but have considerable importance in some societies. Some ferns are used for food, including the fiddleheads of Pteridium aquilinum (bracken), Matteuccia struthiopteris (ostrich fern), and Osmundastrum cinnamomeum (cinnamon fern). Diplazium esculentum is also used in the tropics (for example in budu pakis, a traditional dish of Brunei[47]) as food. Tubers from the "para", Ptisana salicina (king fern) are a traditional food in New Zealand and the South Pacific. Fern tubers were used for food 30,000 years ago in Europe.[48][49] Fern tubers were used by the Guanches to make gofio in the Canary Islands. Ferns are generally not known to be poisonous to humans.[50] Licorice fern rhizomes were chewed by the natives of the Pacific Northwest for their flavor.[51] Some species of ferns are carcinogenic, and the British Royal Horticultural Society has advised not to consume any species for health reasons of both humans and livestock.[52]

Ferns of the genus Azolla, commonly known as water fern or mosquito ferns are very small, floating plants that do not resemble ferns. The mosquito ferns are used as a biological fertilizer in the rice paddies of southeast Asia, taking advantage of their ability to fix nitrogen from the air into compounds that can then be used by other plants.

Ferns have proved resistant to phytophagous insects. The gene that express the protein Tma12 in an edible fern, Tectaria macrodonta, has been transferred to cotton plants, which became resistant to whitefly infestations.[53]

Many ferns are grown in horticulture as landscape plants, for cut foliage and as houseplants, especially the Boston fern (Nephrolepis exaltata) and other members of the genus Nephrolepis. The bird's nest fern (Asplenium nidus) is also popular, as are the staghorn ferns (genus Platycerium). Perennial (also known as hardy) ferns planted in gardens in the northern hemisphere also have a considerable following.[54]

Several ferns, such as bracken[55] and Azolla[56] species are noxious weeds or invasive species. Further examples include Japanese climbing fern (Lygodium japonicum), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis) and Giant water fern (Salvinia molesta), one of the world's worst aquatic weeds.[57][58] The important fossil fuel coal consists of the remains of primitive plants, including ferns.[59]

Culture

Pteridology

The study of ferns and other pteridophytes is called pteridology. A pteridologist is a specialist in the study of pteridophytes in a broader sense that includes the more distantly related lycophytes.

Pteridomania

Pteridomania was a Victorian era craze which involved fern collecting and fern motifs in decorative art including pottery, glass, metals, textiles, wood, printed paper, and sculpture "appearing on everything from christening presents to gravestones and memorials." The fashion for growing ferns indoors led to the development of the Wardian case, a glazed cabinet that would exclude air pollutants and maintain the necessary humidity.[60]

Other applications

The Barnsley fern is a fractal named after the British mathematician Michael Barnsley who first described it in his book Fractals Everywhere. A self-similar structure is described by a mathematical function, applied repeatedly at different scales to create a frond pattern.[61]

The dried form of ferns was used in other arts, such as a stencil or directly inked for use in a design. The botanical work, The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland, is a notable example of this type of nature printing. The process, patented by the artist and publisher Henry Bradbury, impressed a specimen on to a soft lead plate. The first publication to demonstrate this was Alois Auer's The Discovery of the Nature Printing-Process.

Fern bars were popular in America in the 1970s and 80s.

Folklore

Ferns figure in folklore, for example in legends about mythical flowers or seeds.[62] In Slavic folklore, ferns are believed to bloom once a year, during the Ivan Kupala night. Although alleged to be exceedingly difficult to find, anyone who sees a fern flower is thought to be guaranteed to be happy and rich for the rest of their life. Similarly, Finnish tradition holds that one who finds the seed of a fern in bloom on Midsummer night will, by possession of it, be guided and be able to travel invisibly to the locations where eternally blazing Will o' the wisps called aarnivalkea mark the spot of hidden treasure. These spots are protected by a spell that prevents anyone but the fern-seed holder from ever knowing their locations.[63] In Wicca, ferns are thought to have magical properties such as a dried fern can be thrown into hot coals of a fire to exorcise evil spirits, or smoke from a burning fern is thought to drive away snakes and such creatures.[64]

New Zealand

Ferns are the national emblem of New Zealand and feature on its passport and in the design of its national airline, Air New Zealand, and of its rugby team, the All Blacks.

Organisms confused with ferns

Misnomers

Several non-fern plants (and even animals) are called ferns and are sometimes confused with ferns. These include:

- Asparagus fern—This may apply to one of several species of the monocot genus Asparagus, which are flowering plants.

- Sweetfern—A flowering shrub of the genus Comptonia.

- Air fern—A group of animals called hydrozoans that are distantly related to jellyfish and corals. They are harvested, dried, dyed green, and then sold as a plant that can live on air. While it may look like a fern, it is merely the skeleton of this colonial animal.

- Fern bush—Chamaebatiaria millefolium—a rose family shrub with fern-like leaves.

- Fern tree—Jacaranda mimosifolia—an ornamental tree of the order Lamiales.

- Fern leaf tree—Filicium decipiens—an ornamental tree of the order Sapindales.

Fern-like flowering plants

Some flowering plants such as palms and members of the carrot family have pinnate leaves that somewhat resemble fern fronds. However, these plants have fully developed seeds contained in fruits, rather than the microscopic spores of ferns.

See also

Notes

- ^ President, International Association of Pteridologists

References

- ^ a b Stein et al 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Pteridophyte Phylogeny Group 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f The Ultimate Family Visual Dictionary. New Delhi: DK Pub. 2012. pp. 118–121. ISBN 978-0-1434-1954-9.

- ^ a b Nitta, Joel H.; Schuettpelz, Eric; Ramírez-Barahona, Santiago; Iwasaki, Wataru; et al. (2022). "An Open and Continuously Updated Fern Tree of Life". Frontiers in Plant Science. 13: 909768. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.909768. PMC 9449725. PMID 36092417.

- ^ Mauseth, James D. (September 2008). Botany: an Introduction to Plant Biology. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 492. ISBN 978-1-4496-4720-9.

- ^ a b c Levyns, M. R. (1966). A Guide to the Flora of the Cape Peninsula (2nd Revised ed.). Juta & Company. OCLC 621340.

- ^ Fernández, Helena; Kumar, Ashwani; Revilla, Maria Angeles (11 November 2010). Working with Ferns: Issues and Applications. Springer. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4419-7162-3.

- ^ Hodgson, Larry (1 January 2005). Making the Most of Shade: How to Plan, Plant, and Grow a Fabulous Garden that Lightens Up the Shadows. Rodale. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-57954-966-4.

- ^ McCausland 2019.

- ^ Understanding the contribution of LFY and PEBP flowering genes to fern leaf dimorphism - Botany 2019

- ^ Fern Structure - Forest Service

- ^ Fern Structure - Forest Service

- ^ "Fern Fronds". Basic Biology. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ Large, Mark F.; Braggins, John E. (2004). Tree Ferns. Timber Press. ISBN 0881926302.

- ^ Underwood 1903.

- ^ Linnaeus 1753.

- ^ a b Schuettpelz et al 2018.

- ^ Swartz 1806.

- ^ a b c d Christenhusz & Chase 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith et al.2006.

- ^ Stace, Clive (2010b). New Flora of the British Isles (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. xxviii. ISBN 978-0-521-70772-5.

- ^ Rai, Hardeep S. & Graham, Sean W. (2010). "Utility of a large, multigene plastid data set in inferring higher-order relationships in ferns and relatives (monilophytes)". American Journal of Botany. 97 (9): 1444–1456. doi:10.3732/ajb.0900305. PMID 21616899., p. 1450

- ^ a b c d Grewe, Felix; et al. (2013). "Complete plastid genomes from Ophioglossum californicum, Psilotum nudum, and Equisetum hyemale reveal an ancestral land plant genome structure and resolve the position of Equisetales among monilophytes". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (1): 1–16. Bibcode:2013BMCEE..13....8G. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-8. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3553075. PMID 23311954.

- ^ Cantino et al 2007.

- ^ a b c Chase & Reveal 2009.

- ^ Schuettpelz 2007, Table I.

- ^ Karol, Kenneth G.; et al. (2010). "Complete plastome sequences of Equisetum arvense and Isoetes flaccida: implications for phylogeny and plastid genome evolution of early land plant lineages". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1): 321–336. Bibcode:2010BMCEE..10..321K. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-321. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3087542. PMID 20969798.

- ^ Li, F-W; Kuo, L-Y; Rothfels, CJ; Ebihara, A; Chiou, W-L; et al. (2011). "rbcL and matK Earn Two Thumbs Up as the Core DNA Barcode for Ferns". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e26597. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626597L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026597. PMC 3197659. PMID 22028918.

- ^ Schneider et al 2009.

- ^ a b Christenhusz et al 2011.

- ^ "Tree viewer: interactive visualization of FTOL". FTOL v1.3.0. 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ Christenhusz & Byng 2016.

- ^ Christenhusz & Chase 2018.

- ^ Christenhusz et al 2018.

- ^ UCMP 2019.

- ^ Berry 2009.

- ^ Bomfleur et al 2014.

- ^ Li, F.-W.; Villarreal, J. C.; Kelly, S.; et al. (6 May 2014). "Horizontal transfer of an adaptive chimeric photoreceptor from bryophytes to ferns". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (18): 6672–6677. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6672L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319929111. PMC 4020063. PMID 24733898.

- ^ Genes for seeds arose early in plant evolution, ferns reveal

- ^ Suissa, Jacob S.; Li, Fay-Wei; Moreau, Corrie S. (24 May 2024). "Convergent evolution of fern nectaries facilitated independent recruitment of ant-bodyguards from flowering plants". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 4392. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.4392S. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-48646-x. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 11126701. PMID 38789437.

- ^ EB 2019.

- ^ SLH 2018.

- ^ Schuettpelz 2007, Part I.

- ^ "Ferns Brimming With Life". Science | AAAS. 2 June 2004.

- ^ Walker, Matt (19 February 2010). "A mouse that eats ferns like a dinosaur". BBC Earth News. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- ^ The Ferns (Filicales): Volume 1, Analytical Examination of the Criteria of Comparison: Treated Comparatively with a View to their Natural Classification

- ^ Indigenous Fermented Foods of Southeast Asia. 2015.

- ^ Van Gilder Cooke, Sonia (23 October 2010). "Stone Age humans liked their burgers in a bun". New Scientist, p. 18.

- ^ Revedin, Anna et al. (18 October 2010). "Thirty thousand-year-old evidence of plant food processing". PNAS.

- ^ Pelton, Robert (2011). The Official Pocket Edible Plant Survival Manual. Freedom and Liberty Foundation Press. p. 25. BNID 2940013382145.

- ^ Moerman, Daniel E. (27 October 2010). Native American Food Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary. Timber Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-60469-189-4.

- ^ "Dol Sot Bibimbap". Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ Shukla, Anoop Kumar; Upadhyay, Santosh Kumar; Mishra, Manisha; et al. (26 October 2016). "Expression of an insecticidal fern protein in cotton protects against whitefly". Nature Biotechnology. 34 (10): 1046–1051. doi:10.1038/nbt.3665. PMID 27598229. S2CID 384923.

- ^ "Ferns: A Classic Shade Garden Plant". extension.sdstate.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "Datasheet: Pteridium aquilinum (bracken)". CAB International. 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Datasheet: Azolla filiculoides (water fern)". CAB International. 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "| Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants | University of Florida, IFAS". plants.ifas.ufl.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ Moran, Robbin (2004). A Natural History of Ferns. Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-667-1.

- ^ "Fossils, Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky". www.uky.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ Boyd, Peter D. A. (2 January 2002). "Pteridomania - the Victorian passion for ferns". Antique Collecting. Revised: web version. 28 (6): 9–12. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ^ a b Fractals Everywhere, Boston, MA: Academic Press, 1993, ISBN 0-12-079062-9

- ^ May 1978.

- ^ "Traditional Finnish Midsummer celebration". Saunalahti.fi. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Cunningham, Scott (1999). Cunningham's Encyclopedia of Magical Herbs. Llewellyn. p. 102.

Bibliography

Books

- Christenhusz, Maarten M. J.; Fay, Michael; Byng, James W. (2018). The Global Flora: Special Edition: GLOVAP Nomenclature Part 1. Plant Gateway Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9929993-6-0.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1753). "Cryptogamia: Filices Musci". Species Plantarum: exhibentes plantas rite cognitas, ad genera relatas, cum differentiis specificis, nominibus trivialibus, synonymis selectis, locis natalibus, secundum systema sexuale digestas. Vol. 1. Stockholm: Impensis Laurentii Salvii. pp. 1061–1100, 1100–1130., see also Species Plantarum

- Lord, Thomas R. (2006). Ferns and Fern Allies of Pennsylvania. Indiana, PA: Pinelands Press. Ferns and Fern Allies of Pennsylvania – Thomas Reeves Lord

- Moran, Robbin C. (2004). A Natural History of Ferns. Portland, OR: Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-667-1.

- Ranker, Tom A.; Haufler, Christopher H. (2008). Biology and Evolution of Ferns and Lycophytes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87411-3.

- Swartz, Olof (1806). Synopsis filicum: earum genera et species systematice complectens: adjectis lycopodineis, et descriptionibus novarum et rariorum specierum: cum tabulis aeneis quinque. Kiliae: Impensis Bibliopolii novi academici.

Journal articles

- Berry, Chris (2009). "The Middle Devonian plant collections of Francois Stockmans reconsidered". Geologica Belgica. 12 (1–2): 25–30.

- Bomfleur, B.; McLoughlin, S.; Vajda, V. (20 March 2014). "Fossilized Nuclei and Chromosomes Reveal 180 Million Years of Genomic Stasis in Royal Ferns". Science. 343 (6177): 1376–1377. Bibcode:2014Sci...343.1376B. doi:10.1126/science.1249884. PMID 24653037. S2CID 38248823.

- Cantino, Philip D.; Doyle, James A.; Graham, Sean W.; Judd, Walter S.; Olmstead, Richard G.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Soltis, Pamela S.; Donoghue, Michael J. (1 August 2007). "Towards a Phylogenetic Nomenclature of Tracheophyta". Taxon. 56 (3): 822. doi:10.2307/25065865. JSTOR 25065865.

- Chase, Mark W. & Reveal, James L. (2009). "A phylogenetic classification of the land plants to accompany APG III". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (2): 122–127. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.01002.x.

- Christenhusz, Maarten J. M. & Byng, J. W. (2016). "The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase". Phytotaxa. 261 (3). Magnolia Press: 201–217. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1.

- Christenhusz, M. J. M.; Zhang, X. C.; Schneider, H. (18 February 2011). "A linear sequence of extant families and genera of lycophytes and ferns". Phytotaxa. 19 (1): 7. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.19.1.2.

- Christenhusz, Maarten J. M.; Chase, Mark W. (2014). "Trends and concepts in fern classification". Annals of Botany. 113 (4): 571–594. doi:10.1093/aob/mct299. PMC 3936591. PMID 24532607.

- Christenhusz, Maarten J. M.; Chase, Mark W. (1 June 2018). "PPG recognises too many fern genera". Taxon. 67 (3): 481–487. doi:10.12705/673.2.

- May, Lenore Wile (1978). "The economic uses and associated folklore of ferns and fern allies". The Botanical Review. 44 (4): 491–528. Bibcode:1978BotRv..44..491M. doi:10.1007/BF02860848. S2CID 42101599.

- Melan, M. A.; Whittier, D. P. (1990). "Effects of Inorganic Nitrogen Sources on Spore Germination and Gametophyte Growth in Botrychium Dissectum". Plant, Cell and Environment. 13 (5): 477–82. Bibcode:1990PCEnv..13..477M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.1990.tb01325.x.

- Pryer, Kathleen M.; Schneider, Harald; Smith, Alan R.; Cranfill, Raymond; Wolf, Paul G.; Hunt, Jeffrey S.; Sipes, Sedonia D. (2001). "Horsetails and ferns are a monophyletic group and the closest living relatives to seed plants". Nature. 409 (6820): 618–622. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..618S. doi:10.1038/35054555. PMID 11214320. S2CID 4367248.

- Pryer, Kathleen M.; Schuettpelz, Eric; Wolf, Paul G.; Schneider, Harald; Smith, Alan R.; Cranfill, Raymond (2004). "Phylogeny and evolution of ferns (monilophytes) with a focus on the early leptosporangiate divergences". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1582–1598. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1582. PMID 21652310.

- Pteridophyte Phylogeny Group (November 2016). "A community-derived classification for extant lycophytes and ferns". Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 54 (6): 563–603. doi:10.1111/jse.12229. S2CID 39980610.

- Schneider, Harald; Smith, Alan R.; Pryer, Kathleen M. (1 July 2009). "Is Morphology Really at Odds with Molecules in Estimating Fern Phylogeny?". Systematic Botany. 34 (3): 455–475. doi:10.1600/036364409789271209. S2CID 85855934.

- Schuettpelz, Eric (2007). "Table 1". The evolution and diversification of epiphytic ferns (PDF) (PhD thesis). Duke University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- Schuettpelz, Eric; Rouhan, Germinal; Pryer, Kathleen M.; Rothfels, Carl J.; Prado, Jefferson; Sundue, Michael A.; Windham, Michael D.; Moran, Robbin C.; Smith, Alan R. (1 June 2018). "Are there too many fern genera?". Taxon. 67 (3): 473–480. doi:10.12705/673.1.

- Smith, Alan R.; Kathleen M. Pryer; Eric Schuettpelz; Petra Korall; Harald Schneider; Paul G. Wolf (2006). "A classification for extant ferns" (PDF). Taxon. 55 (3): 705–731. doi:10.2307/25065646. JSTOR 25065646.

- Stein, W. E.; Mannolini, F.; Hernick, L. V.; Landling, E.; Berry, C. M. (2007). "Giant cladoxylopsid trees resolve the enigma of the Earth's earliest forest stumps at Gilboa". Nature. 446 (7138): 904–907. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..904S. doi:10.1038/nature05705. PMID 17443185. S2CID 2575688.

- Radoslaw Janusz Walkowiak (2017). "Classification of Pteridophytes - Short classification of the ferns" (PDF). IEA Paper. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.29934.20809.

- Underwood, L. M. (1903). "The early writers on ferns and their collections.— I. Linnaeus, 1707-1778". Torreya. 3 (10): 145–150. ISSN 0096-3844. JSTOR 40594126.

Websites

- McCausland, Jim (22 February 2019). "Rediscover ferns". Garden plants. Sunset Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "Pteridopsida: Fossil Record". Plants: Pteridopsida. University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Classifying and identifying ferns". Science Learning Hub. The University of Waikato. 3 September 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Mickel, John T.; Wagner, Warren H.; Gifford, Ernest M.; et al. (4 February 2019). "Fern". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Hassler, Michael; Schmitt, Bernd (2 November 2019). "Checklist of Ferns and Lycophytes of the World". World Ferns. Botanical Garden of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Pryer, Kathleen M.; Smith, Alan R.; Rothfels, Carl (2009). "Polypodiopsida". Tree of Life.

- A classification of the ferns and their allies. (Australian National Herbarium)

- A fern book bibliography.

- Register of fossil Pteridophyta

- Watson, L. and M. J. Dallwitz (2004 onwards). The Ferns (Filicopsida) of the British Isles. Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Ferns and Pteridomania in Victorian Scotland.

- Non-seed plant images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

- American Fern Society

- British Pteridological Society

- International Equisetological Association

External links

Data related to Pteridophyta at Wikispecies

Data related to Pteridophyta at Wikispecies Media related to Polypodiopsida at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Polypodiopsida at Wikimedia Commons