Fake building

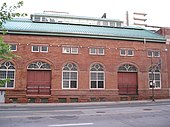

A fake building (also known as a fake house, false-front house, fake façade, or transformer house in specific situations) is a government building, structure, or public utility housing that uses urban and/or suburban camouflage to disguise equipment and city infrastructure facilities that people may consider aesthetically unpleasing in non-industrial neighborhoods.[1][2] These buildings are commonly found in residential towns and cities, where they are intended to blend in with the surrounding architecture and conceal manufactured equipment.

History

Post-Industrial Revolution

After the Industrial Revolution, cities in industrialized countries were required to construct and maintain infrastructure facilities to support city growth. The modern water industry was developed in the early 19th century for that purpose. There were three types of structures that were unique to the water industry: pumping stations, water towers, and dams. In particular, the pumping stations that housed large steam engines in the 19th and early 20th centuries were built intentionally to be symbolic. The building architectures were to communicate a message to the public of safety and reliability, and express their functions. Building designs inherited from beam engine buildings required strong rigid walls and raised floors to support the engines, large arched and multi-story windows to let light in without compromising wall strength, and roof ventilation such as decorative dormers. These functional features formed the principal of "waterworks style." An example of simple waterworks architectural style is Springhead Pumping Station. More elaborate designs were also used to communicate a sacred atmosphere and highlight the critical tasks performed at facilities like sewage pumping stations. An example is Abbey Mills Pumping Station which incorporates baroque eclecticism in its design.[3]

Other types of infrastructure facilities developed narrow styles as well. Those include gas supply, electrical supply, and communications buildings.[4]

Urban infrastructure buildings in this period were intended to be expressive, and not to be concealed from the public. Other examples are Radialsystem (Berlin, Germany, sewage pumping station), Kempton Park engine house, Chestnut Hill Waterworks (Massachusetts, United States), Spotswood Pumping Station (Melbourne, Australia), Palacio de Aguas Corrientes (Buenos Aires, Argentina), Sewage Plant in Bubeneč (Prague, Czech Republic), and R. C. Harris Water Treatment Plant (Toronto, Canada). These buildings are considered to be heritage sites of the global water industry.[5]

Twentieth century

One of the earliest known examples of fake houses was 58 Joralemon Street in New York. This property was acquired by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company in 1907 and gutted for the use of ventilating underground transportation.[6] As a historic building, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission had jurisdiction over this project. The local community wanted the façade to be historically appropriate and compatible with the neighborhood.[7]

Urban and suburban camouflage on a large scale can be seen in early 1911 when substations were first introduced in Toronto, Canada. During this period, electronic converters were housed within grandiose abodes rather than being unenclosed or disguised. Many of these fake building designs were meant to imitate civic buildings such as museums and city halls.[8][9] After the end of World War II, suburban developments began to flourish internationally.[10] Due to this shift in constructed society, electric demand grew exponentially, and architects were called to find openings for new substations. Harold Alphonso Bodwell, a utility employee appointed as a lead designer in Toronto, introduced the idea of disemboweling unused housing for these substations.[11] Eventually, Toronto Hydro built house-shaped substations with slight variations from six base models ranging from ranch-style houses to Georgian mansions. Throughout the 20th century, the company built hundreds of these fake houses.[9]

In 1963, a property owner in Prairie Village, Kansas, United States gave $300,000 in capital improvements to Johnson County Wastewater, a wastewater management authority, to build a fake house for a local sewage pumping station which would blend into the neighborhood. Not everyone in the neighborhood knew about the existence of the facility as they did not experience any smell of sewage in the area. The authority also built another fake house, this time for a pumping station.[12]

Usage and placement

Municipalities across the globe use the fake house design strategy for numerous purposes. In Los Angeles, California, many of these structures conceal oil rigs.[14] Other assignments include pump stations[15] and subway ventilation shafts. These false houses are intended to blend in with their surroundings. Other façades can be discovered in New York City, New York,[16] Los Angeles, California,[17] Paris, France,[18] and London, United Kingdom.[19]

In other contexts, fake buildings may be used beyond hiding city infrastructure for purely aesthetic reasons. Some conceal the locations of secret facilities, such as chalets in Switzerland that are used to hide military installations.[20]

Known locations

The following are further examples of fake buildings:

For ventilation

- 145 rue La Fayette. 10th arrondissement of Paris.

- Affiliated buildings of Holland Tunnel. New York City, New York, United States.

- 58 Joralemon Street for rapid transit. Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn, New York, United States.

- 23/24 Leinster Gardens for rapid transit. London, England, United Kingdom.

For power conversion

- Strecker Memorial Laboratory. Southpoint Park, Roosevelt Island, New York City, United States.

- 51 W Ontario Street. Chicago, Illinois, United States.

- 640 Millwood Road. Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 29 Nelson Street. Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

For water and wastewater management

- WNY1 solids/floatables screen facility of North Hudson Sewerage Authority, south of 6400 Anthony M. Defino Way, West New York, New Jersey, United States.[13]

- H1 Screening and Wet Weather Pump Station at 99 Observer Highway, Hoboken, New Jersey, United States.[21]

- Belindeer Pump Station of Johnson County Wastewater at 5700 Belinder Avenue, Fairway, Kansas, United States.[22]

- Nall Avenue Holding Station of Johnson County Wastewater at 7490 Nall Avenue, Prairie Village, Kansas, United States.[22]

Design

Most fake buildings are similar to the design of their surrounding buildings, but they are not always built this way. Some examples also may be less convincing to a viewer, due to design flaws caused by the contained equipment or other difficulties. These flaws include blacked-out windows;[24][25][26] the lack of a roof,[27][25][28] doorway, window panes,[27] or some enclosed walls;[27] gated extrusions; warning signs; and some 3D components printed on (rather than replicated with actual materials).[18]

Other design elements that may reveal the existence of fake buildings include industrial doors and windows that would not normally be installed in a home, unusually pristine landscaping, heavy fencing, and many security cameras.[9]

In municipalities that require public consultations for the construction of public facilities, the general public may have a great influence in the designs of fake buildings. It is not always the case that locals request designs that resemble residential homes. For example, when the City of Hoboken presented an initial design of a structure to house a new flood pump station, there was a public outcry because the building looked more like a colonial townhouse, with some saying it dishonored the industrial heritage of the city. The final design was completely changed into a modern building with design similarities to a nearby transportation building.[29]

Some fake buildings have designs that imitate other structures to match their surrounding areas. An electrical substation in an urban neighborhood of Washington, DC, is disguised as an old train station. Another substation in a mixed commercial and residential area of DC imitates an office building. In a more rural area of Gaithersburg, Maryland, a substation is designed to look like a large barn with a metal silo on the side, so it might blend into nearby farmland.[30]

References

- ^ Collyer, Robin. "ARTIST PROJECT / TRANSFORMER HOUSES". Cabinet Magazine. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Pyzyk, Katie. "Fake buildings shrouding transit infrastructure are hiding in plain sight". Smart Cities Dive. Industry Dive. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Douet, James (1 January 1992). Temples of Steam Waterworks Architecture in the Steam Age. Bristol Polytechnic. ISBN 1871056659. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Infrastructure: Utilities and Communication. Historic England. December 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Douet, James (25 January 2018). The Water Industry as World Heritage (PDF). The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Fresh Air for Tunnel: Plant Site Purchased". New-York Tribune. 1907-03-23. p. 4. Retrieved 21 December 2022 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Gill, John Freeman (26 December 2004). "A Puzzle Tucked Amid the Brownstones". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Turning on Toronto: A History of Toronto Hydro". Toronto. City of Toronto. 23 November 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Mars, Roman (5 October 2020). "See the secret buildings that make cities run". Fast Company. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ Nicolaides, Becky; Wiese, Andrew (2017). "Suburbanization in the United States after 1945". Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.64. ISBN 978-0-19-932917-5. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Power Houses: Toronto Hydro's Camouflaged Substations". Web Urbanist. Webist Media. 5 February 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ McDowell, Sean (21 January 2014). "Wastewater pump center concealed within Prairie Village house". FOX4KC WDAF-TV. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b Combined Sewer System Characterization Report for the River Road Wastewater Treatment Plant (PDF). North Hudson Sewerage Authority. 1 July 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ Kholstedt, Kurt (23 July 2018). "Hollywood-Worthy Camouflage: Uncovering the Urban Oil Derricks of Los Angeles". 99% Invisible. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Chan, Casey (21 January 2014). "This normal looking house is fake and actually hides a pump station". Gizmodo. G/O Media Inc. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Tedesco, Lianna (12 October 2021). "NYC Is Full Of Fake Facades, And This Is What To Know About Finding Them". The Travel. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Matthew, Zoie (5 February 2018). "4 Oil Wells Hidden in Plain Sight in L.A." Los Angeles Magazine. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b Moggia, Silvia (17 January 2017). "Did you know about the fake painted buildings in Paris?". Silvia's Trips. Silvia Moggia. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "23-24 Leinster Gardens, London's False-Front House". Britain Express. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Fake Chalets: Unmasking the Bunkers disguised as Quaint Swiss Villas". Messy Nessy. 13 THINGS LTD. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Hortillosa, Summer Dawn (17 October 2011). "Wet weather pump station in Hoboken now ready to alleviate city's flooding woes". The Jersey Journal. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b Living the Pipe Dream (PDF). Johnson County Wastewater. p. 13.

- ^ "20 unusual places to see in Paris". Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ Batemen, Chris (18 February 2015). "The transformer next door". Spacing Toronto. Spacing. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b Nguyen, Clinton (21 June 2015). "8 fake buildings that are actually secret portals". Business Insider. Insider Inc. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Carlson, Jen (8 February 2022). "It's a historic townhouse, but 58 Joralemon is also a secret subway exit and shaft house owned by the MTA". Gothamist. New York Public Radio. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b c "No, say it ain't faux! M.T.A. plant hits the fan". amNY. Schneps Media. October 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "145 Rue Lafayette". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Colaneri, Katie (23 August 2010). "Hoboken reveals new wet weather pump station design". The Jersey Journal. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ Basch, Michelle (13 December 2017). "Is it a house? Is it a barn? What Pepco's hiding in plain sight in your neighborhood". WTOP News. Retrieved 8 February 2024.