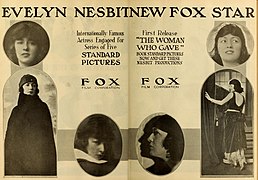

Evelyn Nesbit

Evelyn Nesbit | |

|---|---|

1903 photograph by Gertrude Käsebier | |

| Born | December 25, 1884, or December 25, 1885 Tarentum, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | January 17, 1967 (aged 82) or January 17, 1967 (aged 81) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Other names | Evelyn Nesbit Thaw |

| Occupation(s) | Model, chorus girl, actress |

| Years active | 1899-1967 |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Russell William Thaw |

Florence Evelyn Nesbit (December 25, 1884 or 1885 – January 17, 1967) was an American artists' model, chorus girl, and actress. She is best known for her career in New York City, as well as her husband, railroad scion Harry Kendall Thaw's obsessive and abusive fixation on both Nesbit and architect Stanford White, which resulted in White's murder by Thaw in 1906.

As a model, Nesbit was frequently photographed for mass circulation newspapers, magazine advertisements, souvenir items and calendars. When in her early teens, she had begun working as an artist's model in Philadelphia. Nesbit continued after her family moved to New York, posing for artists including James Carroll Beckwith, Frederick S. Church and notably Charles Dana Gibson, who idealized her as a "Gibson Girl". She began modeling when both fashion photography (as an advertising medium) and the pin-up (as an art genre) were beginning to expand.

Nesbit entered Broadway theatre, initially as a chorus line dancer before becoming a featured star. A variety of wealthy men vied for her company including Stanford White, 32 years her senior. In 1905, Nesbit married Thaw, a multi-millionaire about 14 years her senior with a history of mental instability and abusive behavior. The next year, on June 25, 1906, Thaw shot and killed White at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden.

The press called the resulting court case the "Trial of the Century", coverage of which was sensational. Nesbit testified that White had befriended her and her mother, but had drugged and then raped her when she was unconscious.[1][2][3] Nesbit and White had also begun an ongoing relationship after the alleged rape incident. Thaw was said to have killed White in retaliation for his actions with Nesbit, based on his own obsession with her.

Nesbit visited Thaw while he was confined to mental asylums. She toured Europe with a dance troupe, and her son, Russell Thaw, was born in Germany. Later she took the boy with her to Hollywood, where she appeared as an actress in numerous silent films. Nesbit wrote two memoirs about her life, published in 1914 and 1934. She died in Santa Monica, California, in 1967.

Early life

Florence Evelyn Nesbit was born in Natrona, Pennsylvania, a small town near Pittsburgh, on December 25 (Christmas Day) in either 1884 or 1885.[4] The year of her birth remains unconfirmed, as the local records were destroyed in a fire and Evelyn said she was unsure of the date.[5] In later years, Nesbit confirmed that her mother sometimes added several years to her age to circumvent child labor laws.[6][7][page needed]

Nesbit was the daughter of Winfield Scott Nesbit and his wife, Evelyn Florence (née McKenzie), and was of Scots-Irish ancestry. Her father was an attorney, and her mother was a homemaker. Nesbit later said that she had an especially close relationship with her father and tried to please him by her accomplishments; he in turn encouraged her curiosity and self-confidence. As she loved reading, Nesbit's father chose books for her and set up a small library for her use, consisting of fairy tales, fantasies, and books regarded typically as of interest to boys only – the "pluck and luck" stories that were popular in that era. When Nesbit showed an interest in music and dance, her father encouraged her to take lessons.[8]

The Nesbit family moved to Pittsburgh around 1893. When Nesbit was about ten years old, her father died suddenly at age 40. Her family was left penniless; they lost their home and all their possessions were auctioned off to pay outstanding debts. Nesbit's mother was unable to find work using her dressmaking skills. Dependent on the charity of friends and relatives, the family lived as nomads and shared a single room in a series of boardinghouses. Nesbit's younger brother Howard was often sent to live with friends or relatives for periods of time.[8] Nesbit's mother was eventually given money to rent a house to use as her own boardinghouse, securing a source of income. She sometimes assigned young Evelyn (aged about 12) to the duty of collecting the rent from boarders. "Mamma was always worried about the rent," Nesbit later recalled. "[I]t was too hard a thing for her to actually ask for every week, and it never went smoothly."[9] Nesbit's mother lacked the temperament or savvy to run a boardinghouse, and the venture failed.[9]

With their financial prospects continuously dim, the Nesbit family moved to Philadelphia in 1898. A friend had advised Nesbit's mother that relocating to Philadelphia could open opportunities for her employment as a seamstress. Evelyn and Howard were sent to an aunt and then transferred for care to a family in Allegheny, whose acquaintance their mother had made some years earlier.[10] Mrs. Nesbit indeed gained a job, not as a seamstress, but as a sales clerk at the fabric counter of Wanamaker's department store. She sent for her children, and both 14-year-old Evelyn and 12-year-old Howard also became Wanamaker employees, working twelve-hour days for six days a week.

It was here that Nesbit had a chance encounter with an artist who was struck by her beauty. She asked Nesbit to pose for a portrait, which her mother agreed to after verifying the artist was a woman. Nesbit sat for five hours and earned one dollar (equivalent to $31 in 2023). She was introduced to other artists in the Philadelphia area and became a favorite model for a group of reputable illustrators, portrait painters and stained-glass artisans. In later life, she explained: "When I saw I could earn more money posing as an artist's model than I could at Wanamaker's, I gave my mother no peace until she permitted me to pose for a livelihood."[11]

Modeling career

In June 1900, Mrs. Nesbit, leaving her children in the care of others, relocated to New York City to seek work as a seamstress or clothing designer. However, she did not succeed in this competitive world.[12] In November 1900 she finally sent for her children, although she had no work. The family shared a single back room in a building on 22nd Street in Manhattan.[13]

Nesbit's mother finally used letters of introduction given by Philadelphia artists, contacting painter James Carroll Beckwith, whose primary patron was John Jacob Astor. Beckwith was both a respected painter and instructor of life classes at the Art Students League. He took a protective interest in the young Nesbit and provided her with letters of introduction to other legitimate artists, such as Frederick S. Church, Herbert Morgan and Carle J. Blenner.

Nesbit's mother was forced to take on managing her daughter's career, proving unable to provide either business acumen or guardianship for her daughter. In a later interview with reporters, she maintained: "I never allowed Evelyn to pose in the altogether". Two artworks, one by Church and another by Beckwith in 1901, contradict her statement, as they display a skimpily clad or partially nude Evelyn.[14]

Nesbit became one of the most in-demand artists' models in New York. Photographers Otto Sarony and Rudolf Eickemeyer were among those who worked with her. Charles Dana Gibson, one of the country's most renowned artists of the era, used Nesbit as the model for one of his best-known "Gibson Girl" works. Titled Woman: The Eternal Question (c.1903), the portrait features Nesbit in profile, with her luxuriant hair forming the shape of a question mark.[15]

Elsewhere, Nesbit was featured on the covers of numerous women's magazines, including Vanity Fair, Harper's Bazaar, The Delineator, Ladies' Home Journal and Cosmopolitan.[16] She appeared in fashion advertising for a wide variety of products; and was also showcased on sheet music and souvenir items – beer trays, tobacco cards, pocket mirrors, postcards, and chromolithographs. Nesbit often posed in vignettes, dressed in various costumes. These photo postcards were known as mignon (sweet, lovely), as their pictorials were of a suggestive sensuality in contrast to the graphic, notorious "French postcards" of the day. She also posed for calendars for Prudential Life Insurance, Coca-Cola and other corporations.[17]

The use of photographs of young women in advertising, referred to as the "live model" style, was just beginning to be widely used and to supplant illustration. Nesbit modeled for Joel Feder, an early pioneer in fashion photography. She found such assignments less strenuous than working as an artist's model, as posing sessions were shorter. The work was lucrative. With Feder, Nesbit earned $5 for a half-day shoot and $10 for a full day – equivalent to $301 in 2023. Eventually, the fees she earned from her modeling career exceeded the combined income which her family had earned at Wanamaker's. But the prohibitive cost of living in New York strained their finances.[16]

Chorus girl and actress

Over time Nesbit became disaffected with the long hours spent in confined environments, maintaining the immobile poses required of a studio model. Her popularity in modeling had attracted the interests of theatrical promoters, some legitimate and some disreputable, who offered her acting opportunities.[18] Nesbit pressed her mother to let her enter the theatre world, and Mrs. Nesbit ultimately agreed to let her daughter try this new way to augment their finances.

An interview was arranged for the aspiring performer with John C. Fisher, company manager of the wildly popular play Florodora, then enjoying a long run at the Casino Theatre on Broadway. Mrs. Nesbit's initial objections were softened by the knowledge that some of the girls in the show had managed to marry millionaires. In July 1901, costumed as a "Spanish maiden", Nesbit became a member of the show's chorus line, whose enthusiastic public dubbed them the "Florodora Girls". Billed as "Florence Evelyn", the new chorus girl was called "Flossie the Fuss" by the cast, a nickname which displeased her. She changed her theatrical name to Evelyn Nesbit.[19]

After her stint with Florodora ended, Nesbit sought out other roles. She won a part in The Wild Rose, which had just come to Broadway. After an initial interview with Nesbit, the show's producer, George Lederer, sensed he had discovered a new sensation. He offered her a contract for a year and, more significantly, moved her out of the chorus line and into a position as a featured player – the part of the Gypsy girl "Vashti". Nesbit's new role generated much publicity, and she was hyped in the gossip columns and theatrical periodicals of the day. On May 4, 1902, the New York Herald showcased Nesbit in a two-page article, enhanced by photographs, promoting her rise as a new theatrical light and recounting her career from model to chorus line to key cast member. "Her Winsome Face to be Seen Only from 8 to 11pm", the newspaper title announced to the public. The press coverage invariably touted her physical charms and potent stage presence; acting skills were rarely mentioned.[20]

In 1902 Nesbit portrayed Miss Always There in the musical Tommy Rot.[21]

Relationships

Stanford White

As a chorus girl on Broadway in 1901, at the age of 15 or 16, Nesbit was introduced to Stanford White, a prominent New York architect, by Edna Goodrich,[22] who was also a member of the company of Florodora. White, known as "Stanny" by close friends and relatives, was 46 years old at the time of the meeting.[1] Despite being married with a son, White had an independent social life. She was initially struck by White's imposing size, which she later said "was appalling", while also remarking that he seemed "terribly old".

White invited Nesbit and Goodrich to lunch at his multi-floor apartment on West 24th Street, the entrance of which was next to the back delivery entrance of the toy store FAO Schwarz. Also in attendance was another male guest about White's age, Reginald Ronalds. Nesbit later described being overwhelmed by White's expensive furnishings and luxurious apartment.[23] The luncheon was as extravagant as the setting.[23] Afterward, the party went two flights up to a room decorated in green, where a large, red velvet swing was suspended from the ceiling. Nesbit agreed to sit in it, and White pushed her. The four played spontaneous games involving the swing.[24]

White appeared to be a witty, kind and generous man. The wealthy socialite was described in newspapers as "masterful", "intense" and "burly yet boyish". He impressed both Nesbit and her mother as an "interesting companion".[25] White sponsored Nesbit, her mother and brother for better living quarters, moving them into a suite at the Wellington Hotel, which he also furnished.[26] He soon won over Mrs. Nesbit; in addition to providing the apartment, he paid for her brother Howard to attend the Chester County Military Academy (now Widener University) near Philadelphia. He also persuaded Mrs. Nesbit to take a trip to visit friends in Pittsburgh, assuring her he would watch over her daughter Evelyn.[27]

Nesbit later said that while her mother was out of town, she had dinner and champagne at White's apartment, capped by a tour ending at the "mirror room", which was furnished only with a green velvet sofa, and that she then changed into a yellow satin kimono at White's request. She said this was her last memory until she awoke naked in bed next to an also-naked White and saw blood on the sheets, marking the loss of her virginity.[28] Despite her later allegation of date rape, Nesbit allowed White to be her regular lover and close companion for some time. She said that as their relationship faded, she discovered he had also had affairs with other female minors whose names he had recorded in a "little black book".[citation needed]

Personal life

John Barrymore

John Barrymore became entranced with Nesbit's performance in The Wild Rose and attended the show at least a dozen times. The two met at a lavish party given by White, who had invited Barrymore, the brother of his friend, stage actress Ethel Barrymore. In 1902, a romance blossomed between Nesbit and Barrymore, then 21, close to her own age. Barrymore was witty and fun-loving, and Nesbit became smitten with him. After an evening out, the couple often returned to his apartment, staying until the early-morning hours. Barrymore was casually pursuing a career as illustrator and cartoonist. Although he showed some promise in his chosen field, his salary was small and he behaved irresponsibly with the family money. Both White and Nesbit's mother considered him an unsuitable match for Nesbit, and both were greatly displeased when they found out about the relationship.[29]

White worked to separate the couple by arranging for Nesbit's enrollment at a boarding school in New Jersey, administered by Mathilda DeMille, mother of film director Cecil B. DeMille.[30][full citation needed] In the presence of both Mrs. Nesbit and White, Barrymore had asked Nesbit to marry him, but she turned him down.

Several decades later, in 1939, Barrymore and Nesbit had a tearful reunion in Chicago. He was in town starring in My Dear Children and, one night after the show, found his way to Gene Harris' Club Alabam, where she was appearing on stage. According to legend, Barrymore announced to the room that Nesbit was his first love.[31]

Harry Kendall Thaw

Aside from her relationship with Barrymore, Nesbit was involved with other men who vied for her attention. Among those were the polo player James Montgomery "Monte" Waterbury and the young magazine publisher Robert J. Collier. Even as she had these relationships, White still remained a potent presence in Nesbit's life and served as her benefactor.

Nesbit eventually became involved with Harry Kendall Thaw, the son of a Pittsburgh railroad baron. With a history of pronounced mental instability dating to his childhood, Thaw, heir to a $40 million fortune, led a reckless, self-indulgent life.[32] He had attended some forty performances of The Wild Rose, over nearly a year. Even before he met Nesbit, Thaw had developed a resentment of White, believing that he had blocked Thaw's acceptance in New York social circles and was a womanizer who preyed on young women.[33] Thaw may have chosen Nesbit because of her relationship with White.[33]

Through an intermediary, Thaw arranged a meeting with Nesbit, introducing himself as "Mr. Munroe". He maintained this subterfuge while giving her items and money. One day he confronted Evelyn and said: "I am not Munroe ... I am Harry Kendall Thaw, of Pittsburgh!"[34] She did not react with such surprise as he had expected; she was already used to attracting the attention of wealthy men.

Trip to Europe

In early 1903, while at boarding school, Nesbit underwent emergency surgery. The official diagnosis was acute appendicitis; however some sources, including Nesbit's grandson, have speculated that she had been pregnant (perhaps by Barrymore) and had an abortion. However, under oath at Thaw's murder trials, both Nesbit and Barrymore denied that she was pregnant or had an abortion.[35]

Thaw became solicitous, ensuring that Nesbit received the best medical care available. He suggested that she should go on a European trip, convincing Nesbit and her mother that this would hasten the young woman's recovery. Evelyn's mother accompanied them for propriety. Thaw created a hectic itinerary and rate of travel. Tensions mounted between mother and daughter, and Mrs. Nesbit insisted on returning to the United States. Thaw took Nesbit alone to Paris, leaving Mrs. Nesbit in London.[36] In Paris, Thaw pressed Evelyn to become his wife, but she refused. Aware of his obsession with female chastity, she could not accept his marriage proposal without revealing the truth of her relationship with White. Thaw continued to interrogate her, and ultimately Evelyn told him of White's assault. Thaw accused her mother of being an unfit parent.[37]

Thaw and Evelyn continued their travel through Europe, visiting sites devoted to the cult of virgin martyrdom. In Domrémy, France, the birthplace of Joan of Arc, Thaw wrote in the visitor's book: "she would not have been a virgin if Stanford White had been around."[38] In Austria-Hungary, Thaw took Evelyn to the gothic Katzenstein Castle, where he had the three servants in residence – butler, cook, and maid – kept at one end of the building; while he and Nesbit had isolated quarters at the opposite end.[39] Thaw locked Evelyn in her room, then beat her with a whip and sexually assaulted her over a two-week period. Afterward, he was apologetic and upbeat.[40]

After returning to New York, Nesbit talked to friends about her ordeal. Others shared stories about Thaw and a propensity toward myriad addictive behaviors. Several men told her that Thaw "took morphine" and "was crazy".[41]

Marriage

Nesbit knew her connection with White had already compromised her reputation; if the full extent of their involvement became common knowledge, no respectable man would make her his wife. Nesbit also resented White for failing to tell her about Thaw's excesses and derangement. As a teenager, she had spent her formative years thrust into the adult society of artists and theatre people; her development had proceeded without the companionship of contemporaries of her own age. Her mother had remarried, and although she had been an inept guardian before, their estrangement was now complete. Nesbit was desperate to escape the poverty which she and her family had long suffered.[42]

Thaw continued to pursue Nesbit for marriage, promising that following their union he would live the life of a "Benedictine monk". With a perverted sense of justice, and a show of magnanimous charity, he assured Nesbit he had forgiven her for her relationship with White.[43] Nesbit finally consented to marry Thaw. His mother agreed to the marriage, on the condition that Nesbit give up the theatre and modeling, and refrain from talking about her past life.[44]

Nesbit married Thaw on April 4, 1905.[45] For her wedding dress, Thaw chose a black traveling suit decorated with brown trim. Newspapers announced that the new Mrs. Thaw was now the "Mistress of Millions".[46] The two took up residence in Lyndhurst, the Thaw family home in Pittsburgh. Isolated with Thaw's mother and her like-minded social group of strict Presbyterians, Nesbit became the proverbial bird in a gilded cage. In later years, she said that the Thaws had a shallow value system: "the plane of materialism which finds joy in the little things that do not matter – the appearance of ... [things]".[47]

Nesbit had imagined travel and entertaining but found that her husband acted as a pious son. Thaw started a campaign to expose White, corresponding with Anthony Comstock, a crusader for moral probity and the expulsion of vice. Thaw also became convinced that he was being stalked by members of the notorious Monk Eastman Gang of New York, believing White had hired them. Nesbit later said: "[Thaw] imagined his life was in danger because of the work he was doing in connection with the vigilance societies and the exposures he had made to those societies of the happenings in White's flat."[48] In reality, White, not thought to have been aware of Thaw's animus, considered him a poseur of little consequence, categorizing him as a clown and calling him the "Pennsylvania pug", a reference to Thaw's baby-faced features.

Murder of Stanford White

Thaw and Nesbit visited New York in June 1906 before boarding a luxury liner bound for a European holiday. Late that day, Thaw said that he had obtained tickets for the premiere of Mam'zelle Champagne, written by Edgar Allan Woolf, at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. They first stopped at the Cafe Martin for dinner, where they happened to see White, before going to the theatre. Despite the heat, Thaw wore a long black overcoat over his tuxedo and refused to remove it.

At 11:00 pm, as the stage show was coming to a close, White appeared and took his place at a table customarily reserved for him. Spotting his arrival, Thaw approached him several times, each time withdrawing. During the finale, "I Could Love A Million Girls", Thaw produced a pistol and, from two feet away, fired three shots into White's head and back, killing him instantly.[49] Thaw addressed the crowd, but witness reports varied as to his words. He said (roughly): "I did it because he ruined my wife! He had it coming to him! He took advantage of the girl and then abandoned her! ... You'll never go out with that woman again!"[50] In his book The Murder of Stanford White (2011), Gerald Langford quoted Thaw as saying, "You ruined my life", or, "You ruined my wife".

The crowd initially thought the incident might be a practical joke but became alarmed upon realizing White was dead. Thaw brandished the pistol and was taken into police custody. Nesbit managed to extricate herself from the ensuing chaos on the Madison Square rooftop. Not wanting to return to their hotel suite, she took refuge for several days in the apartment of a friend.[51] Years later, Nesbit said of this time: "A complete numbness of mind and body took possession of me ... I moved like a person in a trance for hours afterward."[52]

Press response

As early as the morning following the murder, news coverage became both chaotic and single-minded, and ground forward with unrelenting momentum. A person, a place, or event, no matter how peripheral to the killing of White, was seized on by reporters and hyped as newsworthy copy.[53] Facts were thin, but sensationalist reportage was plentiful in the heyday of yellow journalism. One week after the killing, the film Rooftop Murder was released for public viewing at the nickelodeon theaters, rushed into production by Thomas Edison.[54]

The hard-boiled male reporters of the yellow press were bolstered by a contingent of female counterparts, christened "Sob Sisters"[55] or "The Pity Patrol".[56] Initially, female spectators were allowed in to witness the proceedings. When the case came to trial, the judge banned women from the courtroom – excepting Thaw family members and the female news reporters there on "legitimate business".[57]

Female reporters wrote human interest pieces, emphasizing sentiment and melodrama.[citation needed] They were less sympathetic to Nesbit than Thaw. Nixola Greeley-Smith wrote of Nesbit: "I think that she was sold to one man [White] and later sold herself to another [Thaw]." In an article titled "The Vivisection of a Woman's Soul", Greeley-Smith described Nesbit's unmaidenly revelations as she testified on the stand: "Before her audience of many hundred men, young Mrs. Thaw was compelled to reveal in all its hideousness every detail of her association with Stanford White after his crime against her."[58]

The rampant interest in the murder and those involved were used by both the defense and prosecution to feed malleable reporters any "scoops" that would give their respective sides an advantage in the public forum. News coverage dissected all the key players in what was called the "Garden Murder". One florid account keynoted Nesbit's vulnerability: "Her baby beauty proved her undoing. She toddled as innocently into the arms of Satan as an infant into the outstretched arms of parental love ..." Neither was her mother spared the scrutiny of rogue reporting: "She [her mother] knew better. She also knew she was sacrificing her child's soul for money ...."[59]

Church groups lobbied to restrict the media coverage, asking the government to step in as censor. President Theodore Roosevelt decried the newspapers' penchant for printing the "full disgusting particulars" of the trial proceedings. He conferred with the U.S. Postmaster General on the viability of prohibiting the dissemination of such printed matter through the United States mail, and censorship was threatened but never carried out.[60]

White was hounded in death, excoriated as a man and questioned as an architect. The Evening Standard concluded he was "more of an artist than architect"; his work spoke of his "social dissolution". The Nation was also critical: "He adorned many an American mansion with irrelevant plunder."[61] Richard Harding Davis, a war correspondent and reputedly the model for the "Gibson Man", was angered by the yellow press, saying they had distorted the facts about his friend. Vanity Fair published an editorial lambasting White, which prompted Davis to write a rebuttal published in Collier's, in which he attested that White "admired a beautiful woman as he admired every other beautiful thing God has given us; and his delight over one was as keen, as boyish, as grateful over any others."[61]

"Trial of the Century"

Defense strategy

Thaw's mother was adamant that her son not be stigmatized by clinical insanity. She pressed for the defense to follow a compromise strategy: one of temporary insanity, or what in that era was referred to as a "brainstorm". Acutely conscious that her own family had a history of hereditary insanity, and after years of protecting her son's hidden life, Mrs. Thaw feared his past would be dragged out into the open, ripe for public scrutiny. She proceeded to hire a team of doctors, at a cost of some $500,000, to substantiate that her son's act of homicide constituted a single aberrant act. Nesbit in later years described the determination with which Thaw's family worked to favorably spin his mental deficiency: "the Thaws will put the biggest lunacy experts that money can buy on the stand .... Harry was a madman but they will prove it nicely".[62]

Star witness

Again maneuvering her way through the gauntlet of reporters, the curious public, the sketch artists and photographers enlisted to capture the effect the "harrowing circumstances [had] on her beauty",[63] Nesbit returned to her hotel and the assembled Thaw family. The Thaws may have promised Nesbit a comfortable financial future if she provided testimony at trial favorable to Thaw's case. It was a conditional agreement; if the outcome proved negative, she would receive nothing. The rumored amount of money the Thaws pledged for her cooperation ranged from $25,000 to $1,000,000.[64]

Nesbit's mother remained conspicuously absent throughout her daughter's entire ordeal. She had been cooperating with the prosecution, as Thaw's lawyers considered her culpable of prostituting her daughter to White.[65] Nesbit's brother Howard, who had come to regard White as a father figure, blamed her for his death.[66]

Two trials

Thaw was tried twice for the killing of White. Nesbit testified at both trials; her appearance on the witness stand was an emotionally tortuous ordeal. In open court, she testified to details of her relationship with White, including the night when he allegedly raped her. This was the first time she made the allegation, except in private to Thaw.[67]

Due to the unusual amount of publicity the case had garnered, the jurors were ordered to be sequestered – the first time in the history of American jurisprudence that such a restriction was ordered.[68] The trial proceedings began on January 23, 1907, and the jury went into deliberation on April 11. After forty-seven hours, the jurors emerged deadlocked. Seven had voted guilty, and five voted not guilty. Thaw was outraged that the jurors had not recognized White's killing as the act, as he saw it, of one chivalrous man defending innocent womanhood.[69]

The second trial took place from January through February 1, 1908.[70] At the second trial, Thaw again pleaded temporary insanity. He was found not guilty, on the ground of insanity at the time of the commission of his act. He was sentenced to involuntary commitment for life in the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Beacon, New York. His wealth allowed him to arrange accommodations for his comfort and be granted privileges not given to the general population. Immediately after his confinement, Thaw marshaled the forces of a legal team charged with the mission of having him declared sane; the effort took seven years.[71] The prolonged legal procedures compelled his escape from Matteawan and flight to Canada in 1913; he was extradited to the U.S., but in 1915 was released from custody after being judged sane.

Child

Nesbit gave birth to a son, Russell William Thaw, on October 25, 1910, in Berlin, Germany. She always maintained that her son was Thaw's biological child, conceived during a conjugal visit to Thaw while he was confined at Matteawan, although Thaw denied paternity throughout his life.[72]

In 1911 Nesbit reconciled with her mother, who took on the role of caregiver for the child while Nesbit sought out opportunities to support herself and her son.[73] Russell appeared with his mother in at least six films: Threads of Destiny (1914), Redemption (1917), Her Mistake (1918), The Woman Who Gave (1918), I Want to Forget (1918) and The Hidden Woman (1922). Nesbit's son became an accomplished pilot, placing third in the 1935 Bendix Trophy race from Los Angeles to Cleveland, ahead of Amelia Earhart in fifth place.

Later years

Throughout the prolonged court proceedings, Nesbit had received financial support from Thaw's family. These payments, made to her through the family's attorneys, had been inconsistent and far from generous. After the close of the second trial, the Thaws virtually abandoned her, cutting off all funds. Her grandson, Russell Thaw Jr., recounted a piece of family lore in a 2005 interview with the Los Angeles Times: purportedly, she had received $25,000 from the Thaws after the culmination of the trials. To spite them, she then donated the money to anarchist Emma Goldman, who subsequently turned it over to investigative journalist and political activist John Reed.[74] Nesbit was left to her own resources to provide for herself.[75] She found modest success working in vaudeville and on the silent screen. In 1914, she appeared in Threads of Destiny, produced at the Betzwood studios of film producer Siegmund Lubin.[76]

Nesbit divorced Thaw in 1915.[77] The following year, as soon as the divorce was finalized, she married her dance partner, Jack Clifford. The announcement was front page news. Beginning in 1913, the couple had toured with an extremely successful stage act; in August of that year she gave a dance performance at New York's Victoria Theater, reported as her first performance in the city since 1904.[78] Despite what one reviewer called an "indifferent vaudeville exhibition", in November 1913, they packed the house at Chicago's Auditorium Theater, drawing an overall audience of 7,400 at the venue, turning away hundreds.[79][80] Their marriage did not fare as well. Clifford eventually found his wife's notoriety an insurmountable issue, with his own identity subsumed by that of "Mr. Evelyn Nesbit"; he left her in 1918.[77] After years of legal battles and accusations of infidelity, their divorce was finalized in 1933. Her long-term friend and employer, Dan Blanco, supported her in court. A well-known Chicago nightclub proprietor, Blanco helped engineer Nesbit's cabaret comeback in the 1920s, first at Chicago's Moulin Rouge and later at his own Club Alabam.[81]

In 1921, Nesbit briefly became the proprietor of a tearoom called The Evelyn Nesbit Specialty Food Shop, located in the West 50s in Manhattan, which may have doubled as a speakeasy.[82][83][84]

Following her years in vaudeville, Nesbit transitioned to playing clubs and cabarets around the country. She briefly lent her name to several, including the Evelyn Nesbit Club (Atlantic City) and Chez Evelyn (Manhattan). Fond of Chicago audiences, she frequently played Club Alabam.[85] Through this time, she struggled with chronic financial problems, alcoholism, and morphine addiction.[86] On New Year's Eve 1925, after concluding a six-week engagement at Chicago's Moulin Rouge and before a scheduled appearance in Miami, Nesbit went on a bender and attempted suicide by swallowing disinfectant. For days, headlines across the country once again turned Nesbit's tragic life into front-page news. Later, doctors stated that Nesbit might have died if her stomach had not been full of gin.[87]

Nesbit and Thaw continued to fascinate the public, and the press speculated about the status of their relationship. Following her suicide attempt, one newspaper headline on January 8, 1926, said: "Thaw to Visit Chicago: Reconciliation Rumor". In an interview, Thaw said that he had been paying Nesbit ten dollars a day through an attorney, as a "token of pleasant memories of the past when we were happy".[88] In June 1926, they were photographed together. The pair were on good terms by 1927, when Thaw attended the opening of Nesbit's Manhattan café, Chez Evelyn. In 1929, rumors flew that the couple intended to remarry and that Thaw had purchased an Atlantic City bungalow for Nesbit.[89] When Thaw died in 1947, he bequeathed $10,000 to Nesbit from an estate valued at over $1 million.[90][91]

During the 1930s, Nesbit worked in Panama and added burlesque to her repertoire. In 1939, while sharing the bill with strippers, the then-55-year-old Nesbit told a New York Times reporter: "I wish I were a strip-teaser. I wouldn't have to bother with so many clothes."[74]

On June 5, 1945, Nesbit made news yet again when she was questioned about the murder of Albert Langford, the husband of her friend, Marion Langford. The victim was allegedly slain by one of two men who forcibly entered their Manhattan apartment. Nesbit had a strong alibi for the night of the murder and it was never suggested that she was in any way connected with the crime. Rather, her friendship with the Langfords became just another opportunity to use her name to sell newspapers. The case remains unsolved.[92]

Following Thaw's death in 1947, Nesbit left her home in New York to settle in California, where her son, Russell W. Thaw, lived in West Los Angeles. She chose to live in downtown Los Angeles, in a neighborhood located just north of Bunker Hill. There she pursued a long-standing interest in sculpting, studying at the Grant Beach School of Arts and Crafts. Following graduation in 1952, she taught classes in sculpting and ceramics.[74][93]

In the summer of 1955, Nesbit served as the technical adviser on the movie The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing (1955), for which she was paid $10,000. The movie recounts her early life and White's murder, blending fiction with fact. While working on the film, Nesbit collapsed from exhaustion.[74][94] She later suffered a stroke in June 1956.[85]

Nesbit published two memoirs, The Story of My Life (1914)[95] and Prodigal Days (1934).[96]

Death

Evelyn Nesbit died in a nursing home in Santa Monica, California, on January 17, 1967, at the age of 82. She had been a resident there for more than a year.[97][98] She was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California.

Stage performances

- Florodora (1901)

- The Wild Rose (1902)

- Tommy Rot (1902)

Filmography

- Threads of Destiny (1914)

- A Lucky Leap (1916)

- Redemption (1917)

- Her Mistake (1918)

- The Woman Who Gave (1918)

- I Want to Forget (1918)

- Woman, Woman! (1919)

- Thou Shalt Not (1919)

- A Fallen Idol (1919)

- My Little Sister (1919)

- The Hidden Woman (1922)

- Broadway Gossip No. 2 (1932 short; as herself)

- Redemption (1917)

- Her Mistake (1918)

- The Woman Who Gave (1918)

- A Fallen Idol (1919)

Representation in other media

- Author Lucy Maud Montgomery, clipped a photograph of Nesbit's from the Metropolitan Magazine, and put it on the wall of her bedroom, as the model for the face of Anne Shirley, the heroine of her book Anne of Green Gables (1908), and as a reminder of her "youthful idealism and spirituality".[99][100]

- Alexander Theroux's novel Laura Warholic; or, the Sexual Intellectual (2007) features an unreferenced 1901 photograph by Eickemeyer of Nesbit on its cover.

Fiction and film

- The Unwritten Law: A Thrilling Drama Based on the Thaw-White Tragedy (1907 film)[101]

- Dalton Trumbo's novel Johnny Got His Gun (1938), has the character Bonni asks the protagonist if she looks like Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, because "all her husbands said she looked just like [her]". (Chapter 14)

- The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing (1955), a fictionalized film about Nesbit

- E. L. Doctorow's historical novel Ragtime (1975), features Nesbit as a main character. It was subsequently adapted as:

- The film Ragtime (1981), in which Evelyn Nesbit was played by Elizabeth McGovern.

- The musical Ragtime (1996). It refers to Stanford White's murder, and the resulting fame for Nesbit. Her character performs the songs "Crime of the Century" and "Atlantic City". She was played by Lynette Perry.

- Keith Maillard's long narrative poem, Dementia Americana (1994), refers to Nesbit.

- Claude Chabrol's film, La Fille coupée en deux (A Girl Cut in Two) (2007), refers to her.

- Don Nigro's dramatic comedy, My Sweetheart's the Man in the Moon (2010), refers to Nesbit.[102]

- In Boardwalk Empire (2010 HBO television series), the character Gillian is loosely based on Evelyn Nesbit.

- Greg Cox's Batman novel The Court of Owls (2019) features a major character named Lydia Doyle who is inspired by Evelyn Nesbit and Audrey Munson to whom the book is dedicated as stated in its epigraph.[103]

References

- ^ a b Uruburu 2008, pp. 99, 105: "nearly three times her age, at forty-six".

- ^ Paul, Deborah Dorian (April 2006). Tragic Beauty: The Lost 1914 Memoirs of Evelyn Nesbit. Lulu. ISBN 9781411696976.[self-published source]

- ^ Rayner, Richard (May 11, 2008). "'American Eve' by Paula Uruburu". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 11, 21–22, 378: "Most don't know that her given name was apparently Florence Mary."

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 21–22, 378. The book gives her birth date as December 25, 1884, while also saying "or perhaps 1885, depending on whose version one takes into account." The end notes say, "As for her correct age, the IRS had to rely on the sworn testimony she gave during the murder trial that she was born during 1884 to decide the issue of her receiving Social Security. But Evelyn was never quite sure if that was the correct year and always believed, as she wrote in a number of letters, that she was born in 1885 (which I also believe, given the furor over her turning 18 in December 1903, referred to in various accounts of events)." Uburu gives Nesbit's age at various places in her book (e.g., in the description of her experience in Europe in 1903), but this is sometimes inconsistent with the 1884 birth date.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 61.

- ^ Mooney, Michael Macdonald, Evelyn Nesbit and Stanford White: Love and Death in the Gilded Age, Morrow, 1976

- ^ a b Uruburu 2008, pp. 24–26.

- ^ a b Uruburu 2008, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 52–55.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Allen, Erin (April 5, 2013). "A Turn-of-the-Century 'True Hollywood Story'". Timeless Stories from the Library of Congress. The Library of Congress. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Uruburu 2008, p. 73.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 153–155.

- ^ Dietz, Dan (2022). "Tommy Rot". The Complete Book of 1900s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 124-126. ISBN 9781538168943.

- ^ Nesbit 1934, p. 3.

- ^ a b Nesbit 1934, p. 27.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 107.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 116.

- ^ Nesbit 1934, p. 37.

- ^ Nesbit 1934, p. 41.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 165–167.

- ^ Park, Edwards. "Pictures of a Tragedy". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 167.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 189.

- ^ a b Uruburu 2008.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 182–88.

- ^ Rasmussen, Cecilia (December 11, 2005). "Girl in the Red Velvet Swing Longed to Flee Her Past". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2012..

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 216–218.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 221.

- ^ "Evelyn's Story" (affidavit in Evelyn Nesbit v. Harry K. Thaw). October 27, 1903. Retrieved July 29, 2012.[permanent dead link]. This affidavit was introduced at the close of the state's case in the Harry Thaw murder trial.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 225.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 229.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 244.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 258.

- ^ Marriage License Docket, No. 1196, Series F; Register of Wills; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; via FamilySearch.org.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 255.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 256.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 282.

- ^ "Thaw Murders Stanford White". The New York Times. June 26, 1906. p. 1..

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 297.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 284.

- ^ "Mrs Thaw Urged Her Husband On". The Washington Post (an alleged statement to police by Nesbit's former friend, actress Edna McClure). July 9, 1906. p. 1.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 301.

- ^ "Sob sister video". IJP.org. USC Annenberg, School for Communication and Journalism. August 21, 2012 – via International Journalists' Programmes..[dead link]

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 318.

- ^ Lutes 2007, p. 74.

- ^ Lutes 2007, pp. 82, 91.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Lutes 2007, p. 76.

- ^ a b Uruburu 2008, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 323.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 289.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 324.

- ^ Lutes 2007, p. 85.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 312.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 333, 339.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 322.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 354.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 358.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 359.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 360, 363.

- ^ Uruburu 2008, p. 362.

- ^ a b c d Rasmussen, Cecilia (December 11, 2005). "Girl in Red Velvet Swing Longed to Flee Her Past". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 18, 2012..

- ^ Uruburu 2008, pp. 358–361.

- ^ Nesbit 1934, p. 276.

- ^ a b Uruburu 2008, p. 368.

- ^ Mantle, Biurns (August 10, 1913). "Miss Evelyn Nesbit (Thaw) Dances and Is Triumphant". Newspapers.com. Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 64.

- ^ "Stage Notes". Newspapers.com. Chicago Tribune. November 24, 1913. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 64–65, 149–150.

- ^ Freeland, David (September 4, 2010). "Gallagher's and Evelyn Nesbit". Gotham Lost & Found (blog). Archived from the original on January 2, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Baker, Lindsay (January 3, 2015). "Evelyn Nesbit: The world's first supermodel". BBC. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 65–75.

- ^ a b Yeck 2019.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 96–101.

- ^ "Harry K. Thaw". Afflictor. Retrieved November 19, 2023. This is a compilation and summary of period news sources; for this quotation: "Thaw to Visit Chicago Reconciliation Rumor". The New York Times. January 8, 1926.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 192–193.

- ^ "Evelyn Nesbit". Neo humanism. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 193–195.

- ^ Yeck 2019, pp. 195.

- ^ Nesbit, Evelyn (1914). The Story of My Life. London: John Long. OCLC 780487288.

- ^ Nesbit 1934.

- ^ "Mrs. Thaw Dies; Early Trial Figure". Los Angeles Times News Service. January 18, 1967. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

Mrs. Thaw, died Tuesday in a convalescent home here. ... After the murder trial she toured Europe with a dancing troupe where a son, Russell Thaw, was born.

[dead link] - ^ "Evelyn Nesbit, 82, Dies In California; Evelyn Nesbit of '06 Thaw Case Dies". The New York Times. Associated Press. January 18, 1967. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

Evelyn Nesbit, the last surviving principal in the sensational Harry K. Thaw-Stanford White murder case of 60 years ago, died in a convalescent home here yesterday, where she had been a patient, for more than a year. She was 82 years old.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Irene Gammel, Looking for Anne of Green Gables: The Story of L.M. Montgomery and her Literary Classic (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2009)". Youtube.com. January 10, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ Gammel, Irene (2009). Looking for Anne of Green Gables: The Story of L. M. Montgomery and her Literary Classic. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- ^ "The Unwritten Law: A Thrilling Drama Based on the Thaw–White Tragedy". IMDb. 1907.

- ^ Nigro, Don (December 2, 2010). My Sweetheart's the Man in the Moon. Samuel French, Inc. ISBN 9780573642388.

- ^ Cox, Greg (2019). Batman: The Court of Owls. Titan Books. ISBN 9781785658167.

Further reading

- Baatz, Simon (2018). The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century. New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 9780316396653.

- Collins, Frederick L. (April 21, 2012). Glamorous Sinners. Literary Licensing. ISBN 9781258294854.

- Gammel, Irene (2008). Looking for Anne of Green Gables: How Lucy Maud Montgomery Dreamed Up a Literary Classic. Key Porter Books. ISBN 9781552639856.

- Langford, Gerald (1962). The Murder of Stanford White. Bobbs-Merrill. ASIN B0007DZ4RY – via Internet Archive.

- Lessard, Suzannah (White's great-granddaughter) (1996). The Architect of Desire: Beauty and Danger in the Stanford White Family. The Dial Press. ISBN 9780385314459 – via Internet Archive.

- Lutes, Jean Marie (2007). Front Page Girls: Women Journalists in American Culture and Fiction: 1880–1930. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801474125 – via Internet Archive.

- Mooney, Michael Macdonald (1976). Evelyn Nesbit and Stanford White: Love and Death in the Gilded Age. William Morrow. ISBN 9780688030797 – via Internet Archive.

- Nesbit, Evelyn (1914). The Story of My Life. London: John Long. OCLC 780487288.

- Nesbit, Evelyn (1934). Prodigal Days: The Untold Story of Evelyn Nesbit. Julian Messner Inc. ISBN 9781411637092.

- Samuels, Charles (1953). The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing. Fawcett Publications. ASIN B0007EYS3O.

- Thaw, Harry K. (1926). The Traitor: Being the Untampered with, Unrevised Account of the Trial and All That Led to It. Dorrance & Company/Argus Publisher. ASIN B001KXL6UE – via Internet Archive.

- Uruburu, Paula (2008). American Eve: Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White, the Birth of the 'It' Girl, and the Crime of the Century. Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781594489938 – via Internet Archive.

- Yeck, Joanne L. (2019). The Blackest Sheep: Dan Blanco, Evelyn Nesbit, Gene Harris and Chicago's Club Alabam. Slate River Press. ISBN 9780983989875.

External links

- Evelyn Nesbit at the Internet Broadway Database

- "Harry Thaw's trial". Urban Sculptures. March 1907. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011 – via Internet Archive.. Scans of a dinner program with jurists' autographs.

- "American Experience: Murder of the Century". PBS.org. Public Broadcasting Service. October 16, 1995. Includes excerpts from Nesbit's autobiographies.

- "The Girl on the Red Velvet Swing". Crime Library. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014.

- Evelyn Nesbit at IMDb