Eurymedon vase

| Eurymedon vase | |

|---|---|

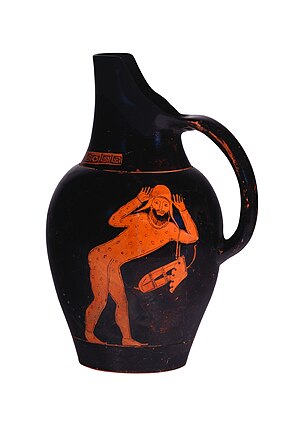

The Eurymedon vase, made circa 460 BC. An inscription on the vase states εύρυμέδον ειμ[í] κυβα[---] έστεκα "I am Eurymedon, I stand bent forward", in probable reference to the Persian defeat and humiliation at the Battle of Eurymedon.[1] | |

| Material | Pottery |

| Created | Circa 460 BC |

| Discovered | Attica |

| Present location | Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany |

Attica region | |

The Eurymedon vase is an Attic red-figure oinochoe,[2] a wine jug attributed to the circle of the Triptolemos Painter made ca. 460 BC, which is now in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (1981.173) in Hamburg, Germany. It depicts two figures; a bearded man (side A), naked except for a mantle, holding his erection in his right hand and reaching forward with his left, while the second figure (side B) in the traditional dress of an Oriental archer bends forward at the hips and twists his upper body to face the viewer while holding his hands open-palmed up before him, level with his head. Between these figures is an inscription that reads εύρυμέδον ειμ[í] κυβα[---] έστεκα, restored by Schauenburg as "I am Eurymedon, I stand bent forward".[3] This vase is a frequently-cited source suggestive of popular Greek attitudes during the Classical period to same-sex relations, gender roles, and Greco-Persian relations.

Interpretation

The vase poses a number of problems of interpretation, such as determining the speaker. Schauenburg ascribes the utterance to the archer; his name is a reference to the Battle of the Eurymedon River[4] sometime in the 460s BC, at which the Athenians prevailed. Though the recipient of this act does not seem unwilling, Schauenburg takes this to embody Greek triumphalism, summed up by J.K. Dover in this way: "[t]his expresses the exaltation of the 'manly' Athenians at their victory over the 'womanish' Persians at the river Eurymedon in the early 460s BC; it proclaims, 'we've buggered the Persians!'"[5] Pinney, however, points out that it is odd that the site of a Hellenic victory should be singled out for such opprobrium, and that the name Eurymedon is an epithet of the Gods also given to epic characters.[6] Furthermore, there is the question of identifying the dress of the participants; the "Greek's" mantle might be a Thracian zaira and his sideburns and beard are characteristically Scythian, while the "Persian's" one-piece suit and gorytos are also typically Scythian,[7] undermining the patriotic reading of the vase by Dover and Schauenburg. Indeed, Pinney would take this as evidence that we are presented here with a burlesque mock epic, and that the comedy, such as it is, lies in the unheroic behaviour of our hero caught in a base act.

Amy C. Smith suggests a compromise between the purely sexual and the overtly political reading with her argument that when the Greek figure announces himself as Eurymedon he adopts the role of personification of the battle in the manner of prosopopoeia or "fictive speaking" familiar from 5th-century tragedy.[8] Thus she claims; "The sexual metaphor succeeds on perhaps three levels: it reminds the viewer of the submissive position in which Kimon had put Persia in anticipation of the Battle of the Eurymedon; of the immediate outcome of the Battle; and of the consequences of the victory, i.e., that the Athenians then found themselves in a position to rape the Barbarians on the Eastern reaches of the Greek world."

The vase has been presented as evidence both for and against the theory advanced by Foucault, Dover, and Paul Veyne[9] that sexual penetration is the privilege of the culturally dominant Greek citizen class over women, slaves, and barbarians. And therefore this image, unique in Attic iconography of sexually pathic behaviour on the part of the Persian, was only permissible because the submissive male figure was a foreigner. James Davidson, however, offers the alternative view that the practices identified and stigmatised in the Greek literature as katapugon (κατάπυγον)[10] and with which we might characterise our archer, is better understood as not as effeminacy but sexual incontinence lacking self-discipline.[11] Thus the wine jug invites the drunken symposiast to bend over in examining the vase to identify with the eimi (ειμί) of the inscription.

Notes

- ^ Schauenburg 1975, restoring the third word as κυβάδε, perhaps related to κύβδα, the term connoting the bent-over, rear-entry position associated with a 3-obol prostitute, see J. Davidson, Courtesans and Fishcakes, 1998, p.170.

- ^ Its form is the Beazley type 7

- ^ Schauenburg 1975, restoring the third word as κυβάδε, perhaps related to κύβδα, the term connoting the bent-over, rear-entry position associated with a 3-obol prostitute, see J. Davidson, Courtesans and Fishcakes, 1998, p.170.

- ^ Thucydides 1.100, possibly 466 BC

- ^ J.K. Dover, Greek Homosexuality, 1978, p.105

- ^ Pinney, 1984. Also the text is nearest our "armed" Greek; it is a convention in vase painting, albeit one not universally observed, that speech is adjacent to the speaker.

- ^ Asserts Pinney, 1984.

- ^ That such anthropomorphic representations are a novelty of early Classical art is argued in Smith, 1999

- ^ In M. Foucault, The Use of Pleasure, 1985; J.K. Dover, op. cit. 1978; P. Veyne, Le Pain et le cirque, 1976.

- ^ LSJ (s.v. κατάπυγος) defines it as given to unnatural lust: generally, lecherous, lewd

- ^ J. Davidson, Courtesans and Fishcakes, 1998, p.170–81.

References

- Davidson, James (1998). Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. Fontana. ISBN 978-0006863434.

- Ferrari Pinney, Gloria (1984). ""For the Heroes Are at Hand"". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 104: 181–183. doi:10.2307/630296. JSTOR 630296.

- Goldhill, S; Osbourne, R (1994). Art and Text in Ancient Greek Culture. Cambridge.

- Kilmer, M.F. (1997). "Rape in early red-figure pottery". In Deacy, S.; Pierce, Karen F. (eds.). Rape in Antiquity: Sexual Violence in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Duckworth.

- Llewellyn-Jones, L. (2017). "Manliness, violation, and laughter: rereading the space and context of the Eurymedon vase" (PDF). Journal of Greek Archaeology.

- Schauenburg, K. (1975). "Eὐρυμέδον εἶμι". AthMitt. 90: 118.

- Smith, Amy C. (1999). "Eurymedon and the Evolution of Political Personifications in the Early Classical Period". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 119: 128–141. doi:10.2307/632314. JSTOR 632314.

- Gerleigner, G.S. (2016). "Tracing Letters on the Eurymedon Vase: On the Importance of Placement of Vase-Inscriptions". In Yatromanolakis, D. (ed.). Epigraphy of Art: Ancient Greek Vase-Inscriptions and Vase-Paintings. Archaeopress Oxford.