Cambodian campaign

| Cambodian campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War and Cambodian Civil War | |||||||

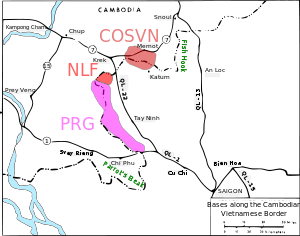

The area of the campaign with detail showing units involved | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lữ Mộng Lan Đỗ Cao Trí Nguyễn Viết Thanh † |

Phạm Hùng (political) Hoàng Văn Thái (military) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ~40,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3,009 wounded 35 missing 1,525 wounded 13 missing[2]: 194 |

U.S. claimed: 11,369 2,328 captured[1]: 158 [2]: 193 (includes civilians according to a CIA official)[3] | ||||||

The Cambodian campaign (also known as the Cambodian incursion and the Cambodian liberation) was a series of military operations conducted in eastern Cambodia in mid-1970 by South Vietnam and the United States as an expansion of the Vietnam War and the Cambodian Civil War. Thirteen operations were conducted by the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) between April 29 and July 22 and by U.S. forces between May 1 and June 30, 1970.

The objective of the campaign was the defeat of the approximately 40,000 troops of the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the Viet Cong (VC) in the eastern border regions of Cambodia. Cambodian neutrality and military weakness made its territory a safe zone where PAVN/VC forces could establish bases for operations over the border. With the US shifting toward a policy of Vietnamization and withdrawal, it sought to shore up the South Vietnamese government by eliminating the cross-border threat.

A change in the Cambodian government allowed an opportunity to destroy the bases in 1970, when Prince Norodom Sihanouk was deposed and replaced by pro-U.S. General Lon Nol. A series of South Vietnamese–Khmer Republic operations captured several towns, but the PAVN/VC military and political leadership narrowly escaped the cordon. The operation was partly a response to a PAVN offensive on March 29 against the Cambodian Army that captured large parts of eastern Cambodia in the wake of these operations. Allied military operations failed to eliminate many PAVN/VC troops or to capture their elusive headquarters, known as the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) as they had left a month earlier, but the haul of captured materiel in Cambodia prompted claims of success.

Preliminaries

Background

The PAVN had been utilizing large sections of relatively unpopulated eastern Cambodia as sanctuaries into which they could withdraw from the struggle in South Vietnam to rest and reorganize without being attacked. These base areas were also utilized by the PAVN and VC to store weapons and other material that had been transported on a large scale into the region on the Sihanouk Trail. PAVN forces had begun moving through Cambodian territory as early as 1963.[4]

Cambodian neutrality had already been violated by South Vietnamese forces in pursuit of political-military factions opposed to the regime of Ngô Đình Diệm in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[4] In 1966, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, ruler of Cambodia, convinced of eventual communist victory in Southeast Asia and fearful for the future of his rule, had concluded an agreement with the People's Republic of China which allowed the establishment of permanent communist bases on Cambodian soil and the use of the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville for resupply.[5]: 127 [6]: 193

During 1968, Cambodia's indigenous communist movement, labeled Khmer Rouge (Red Khmers) by Sihanouk, began an insurgency to overthrow the government. While they received very limited material help from the North Vietnamese at the time (the Hanoi government had no incentive to overthrow Sihanouk, since it was satisfied with his continued "neutrality"), they were able to shelter their forces in areas controlled by PAVN/VC troops.[7]: 55

The US government was aware of these activities in Cambodia, but refrained from taking overt military action within Cambodia in hopes of convincing the mercurial Sihanouk to alter his position. To accomplish this, President Lyndon B. Johnson authorized covert cross-border reconnaissance operations conducted by the secret Studies and Observations Group in order to gather intelligence on PAVN/VC activities in the border regions (Project Vesuvius).[8][5]: 129–130

Menu, coup and North Vietnamese offensive

The new commander of the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), General Creighton W. Abrams, recommended to President Richard M. Nixon shortly after Nixon's inauguration that the Cambodian base areas be bombed by B-52 Stratofortress bombers.[9]: 127 Nixon initially refused, but the breaking point came with the launching of PAVN's Tet 1969 Offensive in South Vietnam. Nixon, angered at what he perceived as a violation of the "agreement" with Hanoi after the cessation of the bombing of North Vietnam, authorized the covert air campaign.[9]: 128 The first mission of Operation Menu was dispatched on March 18 and by the time it was completed 14 months later more than 3,000 sorties had been flown and 108,000 tons of bombs had been dropped on eastern Cambodia.[9]: 127–133

While Sihanouk was abroad in France for a rest cure in January 1970, government-sponsored anti-Vietnamese demonstrations were held throughout Cambodia.[7]: 56–57 Continued unrest spurred Prime Minister/Defense Minister Lon Nol to close the port of Sihanoukville to communist supplies and to issue an ultimatum on March 12 to the North Vietnamese to withdraw their forces from Cambodia within 72 hours. The prince, outraged that his "modus vivendi" with the communists had been disturbed, immediately arranged for a trip to Moscow and Beijing in an attempt to gain their agreement to apply pressure on Hanoi to restrain its forces in Cambodia.[4]: 90

National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger wrote in his memoirs that "historians rarely do justice to the psychological stress on a policy-maker", noting that by early 1970 President Nixon was feeling very much besieged and inclined to lash out against a world he was believed was plotting his downfall.[10]: 606 Nixon had vowed to end the Vietnam War by November 1, 1969 and failed to do so while in the fall of 1969 he had seen two of his nominations to the Supreme Court rejected by the Senate.[10]: 606 Nixon had taken the rejection of his nominations to the Supreme Court as personal humiliations, which he was constantly brooding over. In February 1970, the "secret war" in Laos was revealed, much to his displeasure.[10]: 606–7

Kissinger had denied in a press statement that any Americans had been killed fighting in Laos, only for it to emerge two days later that 27 Americans had been killed fighting in Laos.[11]: 560 As a result, Nixon's public approval ratings fell by 11 points, causing him to refuse to see Kissinger for the next week.[11]: 560 Nixon had hoped that when Kissinger secretly met Lê Đức Thọ in Paris in February 1970 that this might lead to a breakthrough in the negotiations and was disappointed that proved not to be so.[10]: 607

Nixon had become obsessed with the film Patton, a biographical portrayal of controversial General George S. Patton, Jr., which he kept watching over and over again, seeing how the film presented Patton as a solitary and misunderstood genius whom the world did not appreciate, a parallel to himself.[10]: 607 Nixon told his chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, that he and the rest of his staff should see Patton and be more like the subject of the film.[11]: 560 Feeling that events were not working in his favor, Nixon sought some bold, audacious action that might turn his fortunes around.[10]: 607

In particular, Nixon believed that a spectacular military action that would prove "we are still serious about our commitment in Vietnam" might force the North Vietnamese to conclude the Paris peace talks in a manner satisfactory to American interests.[10]: 607 In 1969, Nixon had pulled out 25,000 U.S. troops from South Vietnam and was planning to pull out 150,000 in the near future.[10]: 607 The first withdrawal of 1969 had led to an increase in PAVN/VC activities in the Saigon area, and Abrams had warned Nixon that to pull out another 150,000 troops without eliminating the PAVN/VC bases over the border in Cambodia would create an untenable military situation.[10]: 607 Even before the coup against Sihanouk, Nixon was inclined to invade Cambodia.[10]: 606

On March 18, the Cambodian National Assembly removed Sihanouk and named Lon Nol as provisional head of state. Sihanouk was in Moscow, having a discussion with the Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin, who had to inform him mid-way in the conversation that he had just been deposed.[11]: 558 In response, Sihanouk immediately established a government-in-exile in Beijing allying himself with North Vietnam, the Khmer Rouge, the VC and the Laotian Pathet Lao.[5]: 144 In doing so, Sihanouk lent his name and popularity in the rural areas of Cambodia to a movement over which he had little control.[12]

Sihanouk was revered by the Khmer peasantry as a god-like figure and his endorsement of the Khmer Rouge had immediate effects in rural areas (Silhanouk was less popular in the more educated urban areas of Cambodia).[11]: 558 The reverence for the royal family was such that after the coup Lon Nol went to the Royal Palace, knelt at the feet of the queen mother Sisowath Kossamak and asked for her forgiveness for deposing her son.[11]: 558 In the rural town of Kampong Cham, farmers enraged that their beloved ruler had been overthrown lynched one of Lon Nol's brothers, cut out his liver, cooked it and ate it to symbolize their contempt for the brother of the man who overthrew Sihanouk, who was viewed as the rightful once and future king.[11]: 558

Sihanouk was enraged by the vulgar media attacks by Lon Nol against himself and his family, saying in interview with Stanley Karnow in 1981 that despite the fact that the Khmer Rouge slaughtered much of the royal family including several of his children he still had no regrets about allying himself with the Khmer Rouge in 1970.[10]: 606 His voice raising in fury, Sihanouk told Karnow: "I had to avenge myself against Lon Nol. He was my minister, my officer and he betrayed me".[10]: 606 Sihanouk left Moscow for Beijing, where he was greeted warmly by Zhou Enlai, who assured him that China still recognized him as the legitimate leader of Cambodia, and would back his efforts at restoration.[11]: 558–559

Sihanouk went on Chinese radio to appeal to his people to overthrow Lon Nol, whom he depicted as a puppet of the Americans.[11]: 559 Lon Nol was an intense Khmer nationalist, who detested the Vietnamese, the ancient archenemies of the Khmer nation.[11]: 561 Like many other Khmer nationalists, Lon Nol had not forgotten the southern half of Vietnam was part of the Khmer empire until the 18th century nor had he forgiven the Vietnamese for conquering an area that historically was part of Cambodia.[11]: 561

Though Cambodia had a weak army, Lon Nol had given Hanoi 48 hours to pull its forces out of Cambodia and began the hasty training of 60,000 volunteers to fight the PAVN/VC.[11]: 561 By late March 1970, Cambodia had descended into anarchy as Karnow noted: "Rival Cambodian gangs were hacking each other to pieces, in some instances celebrating their prowess by eating the hearts and livers of their victims."[10]: 607

The North Vietnamese response was swift; they began directly supplying large amounts of weapons and advisors to the Khmer Rouge and Cambodia plunged into civil war.[13][14] Lon Nol saw Cambodia's population of 400,000 ethnic Vietnamese as possible hostages to prevent PAVN attacks and ordered their roundup and internment.[5]: 144 Cambodian soldiers and civilians then unleashed a reign of terror, murdering thousands of Vietnamese civilians.[10]: 606 Lon Nol encouraged pogroms against the Vietnamese minority and the Cambodian police took the lead in organizing the pogroms.[10]: 606

On 15 April for example, 800 Vietnamese men were rounded up at the village of Churi Changwar, tied together, executed, and their bodies dumped into the Mekong River.[7]: 75 They then floated downstream into South Vietnam. Cambodia's actions were denounced by both the North and South Vietnamese governments.[5]: 146 The massacres of Cambodia's Vietnamese minority greatly enraged people in both Vietnams.[10]: 606 Even before the supply conduit through Sihanoukville was shut down, PAVN had begun expanding its logistical system from southeastern Laos (the Ho Chi Minh trail) into northeastern Cambodia.[15]

Nixon was taken by surprise by the events in Cambodia, saying at a National Security Council meeting: "What the hell do those clowns do out there in Langley [CIA]?".[11]: 559 The day after the coup, Nixon ordered Kissinger: "I want Helms [the CIA director] to develop and implement a plan for maximum assistance to pro-U.S. elements in Cambodia".[11]: 559 The CIA began to fly in arms for the Lon Nol regime, through the Secretary of State William P. Rogers told the media about Cambodia on March 23, 1970 "We don't anticipate that any request will be made".[10]: 607 Realizing that he had lost control of the situation, Lon Nol did a volte-face and suddenly declared Cambodia's "strict neutrality".[10]: 606

On March 29, 1970 the PAVN launched an offensive (Campaign X) against the Cambodian Khmer National Armed Forces (FANK), quickly seizing large portions of the eastern and northeastern parts of the country, isolating and besieging or overrunning a number of Cambodian cities including Kampong Cham.[16]: 61 [2]: 153 Documents uncovered from the Soviet archives revealed that the offensive was launched at the explicit request of the Khmer Rouge following negotiations with Nuon Chea.[17] In early-April South Vietnamese Vice President Nguyễn Cao Kỳ twice visited Lon Nol in Phnom Penh for secret meetings to reestablish diplomatic relations between the two countries and agree on military cooperation.[2]: 115 On April 14, 1970, Lon Nol appealed for help, saying that Cambodia was on the verge of losing its independence.[10]: 606

On April 17 the Khmer Republic announced that North Vietnam was invading Cambodia and appealed for assistance in countering North Vietnamese aggression. The U.S. responded immediately, delivering 6,000 captured AK-47 rifles to the FANK and transporting 3–4,000 ethnic Cambodian Civilian Irregular Defense Group program (CIDG) troops to Phnom Penh.[2]: 32 On April 20 the PAVN overran Snuol, on April 23 they seized Memot, on April 24 they attacked Kep and on April 26 they began firing on shipping along the Mekong River, attacked Chhloung District northeast of Phnom Penh and captured Ang Tassom, northwest of Takéo.[2]: 30 After defeating the FANK forces, the PAVN turned the newly won territories over to local insurgents. The Khmer Rouge also established "liberated" areas in the south and the southwestern parts of the country, where they operated independently of the North Vietnamese.[16]: 26–27

Planning

In mid-April 1970 Abrams and Chief of the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff (JGS) General Cao Văn Viên discussed the possibility of attacking the Cambodian base areas. Cao passed on these discussions to South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu who verbally ordered the JGS to instruct ARVN III Corps to liaise with MACV for operations in Cambodia. In late April Thiệu sent a secret directive instructing the JGS to conduct operations in Cambodia to a depth of 40–60 km (25–37 mi) from the border.[2]: 36–40 By April 1970, the PAVN/Khmer Rouge offensive in Cambodia was going well and they had taken all five of Cambodia's northeastern provinces and Kissinger predicated to Nixon that the Lon Nol regime would not survive 1970 on its own.[11]: 564

In response to events in Cambodia, Nixon believed that there were distinct possibilities for a U.S. response. With Sihanouk gone, conditions were ripe for strong measures against the base areas. He was also adamant that some action be taken to support "The only government in Cambodia in the last twenty-five years that had the guts to take a pro-Western stand."[5]: 147 As the poorly-trained FANK went from defeat after defeat, Nixon was afraid that Cambodia would "go down the drain" if he did not take action.[10]: 607

Nixon then solicited proposals for actions from the Joint Chiefs of Staff and MACV, who presented him with a series of options: a naval quarantine of the Cambodian coast; the launching of South Vietnamese and American airstrikes; the expansion of hot pursuit across the border by ARVN forces; or a ground invasion by ARVN, U.S. forces, or both.[5]: 147

Nixon went to Honolulu to offer his congratulations to the Apollo 13 astronauts who had survived a malfunction on their spacecraft and while there, met the Commander in Chief, Pacific Command, Admiral John S. McCain Jr., who was the sort of aggressive, pugnacious military man he admired the most.[11]: 561 McCain drew for Nixon a map of Cambodia that depicted the bloody claws of a red Chinese dragon clutching half of the country and advised Nixon that action was needed now.[11]: 561 Impressed by Admiral McCain's performance, Nixon brought him back to his house in San Clemente, California, to repeat it for Kissinger who was unimpressed.[11]: 562 Kissinger was upset that Thọ had temporarily ended their secret meetings in Paris and shared Nixon's inclinations to lash out against an enemy. Kissinger regarded Thọ like all Vietnamese as "insolent".[11]: 563

During a televised address on April 20, Nixon announced the withdrawal of 150,200 U.S. troops from South Vietnam during the year as part of the Vietnamization program.[11]: 562 This planned withdrawal implied restrictions on any offensive U.S. action in Cambodia. By early 1970, MACV still maintained 330,648 U.S. Army and 55,039 Marine Corps troops in South Vietnam, most of whom were concentrated in 81 infantry and tank battalions.[18]: 319–320

On April 22 Nixon authorized the planning of a South Vietnamese incursion into the Parrot's Beak (named for its perceived shape on a map), believing that "Giving the South Vietnamese an operation of their own would be a major boost to their morale as well as provide a practical demonstration of the success of Vietnamization."[5]: 149 At the meeting of April 22, both Rogers and the Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird proposed waiting to see if the Lon Nol regime could manage to survive on its own.[11]: 563 Kissinger took an aggressive line, favoring having the ARVN invade Cambodia with American air support.[11]: 563

The Vice President, Spiro Agnew, the most hawkish member of Nixon's cabinet, forcefully told Nixon to avoid "pussyfooting" around and invade Cambodia with American troops.[11]: 563–564 On April 23, Rogers testified before the House Appropriations Subcommittee that "the administration had no intentions...to escalate the war. We recognize that if we escalate and get involved in Cambodia with our ground troops that our whole program [Vietnamization] is defeated."[5]: 152

Nixon then authorized Abrams to begin planning for a U.S. operation in the Fishhook region. A preliminary operational plan had actually been completed in March, but was kept so tightly under wraps that when Abrams handed over the task to Lieutenant general Michael S. Davison, commander of II Field Force, Vietnam, he was not informed about the previous planning and started a new one from scratch.[1]: 59 Seventy-two hours later, Davison's plan was submitted to the White House. Kissinger asked one of his aides to review it on April 26, and the National Security Council staffer was appalled by its "sloppiness".[5]: 152

The main problems were the pressure of time and Nixon's desire for secrecy. The Southeast Asia monsoon, whose heavy rains would hamper operations, was only two months away. By the order of Nixon, the State Department did not notify the Cambodian desk at the US Embassy, Saigon, the Phnom Penh embassy, or Lon Nol of the planning. Operational security was as tight as General Abrams could make it. There was to be no prior U.S. logistical build-up in the border regions which might serve as a signal to the communists. U.S. brigade commanders were informed only a week in advance of the offensive, while battalion commanders got only two or three days' notice.[1]: 58–60

Decisions

Not all of the members of the administration agreed that an invasion of Cambodia was either militarily or politically expedient. Laird and Rogers were both opposed to any such operation due to their belief that it would engender intense domestic opposition in the U.S. and that it might possibly derail the ongoing peace negotiations in Paris (they had both opposed the Menu bombings for the same reasons).[9]: 129 Both were castigated by Henry Kissinger for their "bureaucratic foot-dragging."[9]: 83 As a result, Laird was bypassed by the Joint Chiefs in advising the White House on planning and preparations for the Cambodian operation.[19]: 202

Through relations between Laird and Kissinger were unfriendly, the latter felt that it was not proper for the Defense Secretary to be unaware that a major offensive was about to be launched.[11]: 564 Laird advised Kissinger not to inform Rogers, who was due to testify before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, whose chairman, J. William Fulbright, was an opponent of the war.[11]: 564 Laird wanted Rogers to honesty say he was unaware of plans to invade Cambodia to avoid having him indicted for perjury.[11]: 564

Once Laird learned that Nixon was determined "to do something", he suggest only invading the "Parrot's Beak" area with ARVN forces.[10]: 608 Nixon in his 1978 memoirs wrote this recommendation was "the most pusillanimous little nitpicker I ever saw".[10]: 608 Nixon had decided to go for "the big play" for "all the marbles" since he anticipated "a hell of an uproar at home" regardless of what he did.[10]: 608 Lon Nol was not informed in advance that American and South Vietnamese forces were about to enter his nation.[10]: 608

On the evening of April 25 Nixon dined with his friend Bebe Rebozo and Kissinger. Afterward, they screened Patton, which Nixon had seen five times previously. Kissinger later commented that "When he was pressed to the wall, his [Nixon's] romantic streak surfaced and he would see himself as a beleaguered military commander in the tradition of Patton."[5]: 152 The following evening, Nixon decided that "We would go for broke" and gave his authorization for the incursion.[5]: 152

The joint U.S./ARVN campaign would begin on May 1 with the stated goals of reducing allied casualties in South Vietnam, assuring the continued withdrawal of U.S. forces, and enhancing the U.S./Saigon government position at the peace negotiations in Paris.[10]: 607 The task of providing a legal justification was assigned to William Rehnquist, the assistant attorney general, who wrote a legal brief saying in times of war the president had the right to deploy troops "in conflict with foreign powers at their own initiative".[10]: 608

Nixon had testy relations with Congress, so he had Kissinger inform Senators John C. Stennis and Richard Russell Jr. of the plans to invade Cambodia.[11]: 564 Both Stennis and Russell were conservative Southern Democrats who were chairmen of key committees and both were expected to approve of their invasion as indeed they did.[11]: 564 In this way, Nixon could say he did inform at least some leaders of Congress about what was being planned. Congress as a body was kept uninformed of the planned invasion.[10]: 607–608

On April 29, press reports stated that ARVN troops had entered the "Parrot's Beak" area, leading to demands from anti-war senators and congressmen that the president should promise no American troops would be involved, only for the White House to say the president would be giving a speech the next day.[11]: 565–566 Nixon ordered Patrick Buchanan, his speechwriter, to start composing a speech to justify the invasion.[11]: 566

Nixon speaks

In order to keep the campaign as low-key as possible, Abrams had suggested that the commencement of the incursion be routinely announced from Saigon. At 21:00 on 30 April, however, Nixon appeared on all three U.S. television networks to announce that "It is not our power but our will and character that is being tested tonight" and that "the time has come for action." Nixon's speech began 90 minutes after American troops entered the "Fishhook" area.[11]: 566 He announced his decision to launch American forces into Cambodia with the special objective of capturing COSVN, "the headquarters of the entire communist military operation in South Vietnam."[5]: 153

Nixon's speech on national television on April 30, 1970, was called "vintage Nixon" by Kissinger.[10]: 609 Nixon announced that nothing less than America's status as a world power was at stake, saying he had spurned "all political considerations", as he maintained he rather be a one-term president than "be a two-term president at the cost of seeing America become a second-rate power".[10]: 609

Nixon stated: "If, when the chips are down, the world's most powerful nation, the United States of America, acts like a pitiful helpless giant, then the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world".[10]: 609 Karnow wrote that Nixon could have presented the invasion as a relatively minor operation designed to speed up the withdrawal of American forces from South Vietnam by eliminating PAVN/VC bases, but instead by presenting the invasion as necessary to maintain America as a world power made it sound like a far bigger operation than what it really was.[10]: 609

On May 1, 1970, Nixon visited the Pentagon where he received the news that 194 PAVN/VC troops had been killed since the previous day, most by air strikes.[11]: 567 Upon seeing a map, Nixon noticed there other PAVN/VC sanctuaries besides the "Parrot's Beak" and the "Fishhook.[11]: 567 When Nixon asked if they were being invaded as well, he was told that Congress might object.[11]: 567 His response was: "Let me be the judge as far as the political reactions are concerned. Knock them all out so they can't be used against us again Ever".[11]: 567

Lon Nol learned of the invasion when an American diplomat told him, who had in turn learned about it from a Voice of America radio broadcast.[11]: 568 Kissinger sent his deputy, Alexander Haig, to Phnon Penh to meet Lon Nol. Dressed in battle fatigues, Haig refused to share any information with the U.S. embassy staff, instead meeting Lon Nol alone.[11]: 568 Lon Nol complained that the invasion had not helped as it only pushed the PAVN/VC forces deeper into Cambodia and broke down in tears when Haig told him that the Americans would be withdrawing from Cambodia in June.[11]: 568

Operations

Escape of the Provisional Revolutionary Government

Planning for any eventuality the North Vietnamese started planning emergency evacuation routes in the event of a coordinated assault by Cambodians from the west and South Vietnamese from the east. After the Cambodian coup, COSVN was evacuated on 19 March 1970.[20] While the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRG) and PAVN/VC bases were preparing to also move to the north and safety they came under aerial bombardment from B-52 bombers on 27 March.[20] As laid out by the evacuation plans General Hoàng Văn Thái planned to have three divisions to cover the escape.[20]: 180 The 9th Division would block any movement from the ARVN, the VC 5th Division would screen any FANK forces and the 7th Division would provide security to the civilian and military members of the PAVN/VC bases.[20]: 180

Moving across the border in Cambodia on 30 March, elements of the PRG and VC were surrounded in their bunkers by ARVN forces flown in by helicopter.[20]: 178 Surrounded, they waited until nightfall and then with security provided by the 7th Division they broke out of the encirclement and fled north to unite with the COSVN in Kratie Province in what would come to be known as the "Escape of the Provisional Revolutionary Government".[20] Trương Như Tảng, then Minister of Justice in the PRG, recounts that the march to the northern bases was a succession of forced marches, broken up by B-52 bombing raids.[20]: 180

Years later Trương would recall just how "Close [South Vietnamese] were to annihilating or capturing the core of the Southern resistance – elite units of our frontline fighters along with the civilian and much of the military leadership".[20]: 180 After many days of hard marches the PRG reached the northern bases, and relative safety, in the Kratie region. Casualties were light and the march even saw the birth of a baby to Dương Quỳnh Hoa, the deputy minister of health in the PRG. The column needed many days to recover and Trương himself would require weeks to recover from the long march.[citation needed]

The Angel's Wing – Operation Toan Thang 41

On 14 April ARVN III Corps units launched a three-day operation into the "Angel's Wing" area of Svay Rieng Province called Operation Toan Thang (Complete Victory) 41. Mounted by two ARVN armor-infantry task forces, the units began their advance at 08:00 on 14 April. One task force met heavy resistance and killed 182 PAVN and captured 30 for the loss of seven killed. The next day the task forces skirmished with PAVN/VC and uncovered food and material caches and claimed 175 PAVN killed and one captured for losses of one killed. On 16 April, the task forces began their withdrawal, returning to South Vietnam by 12:10 on 17 April. Total PAVN losses, according to the ARVN, were 415 killed or captured and over 100 weapons captured. ARVN losses were eight killed and one Republic of Vietnam Air Force (RVNAF) A-1H Skyraider shot down.[2]: 44–47 Documents captured during the operation and prisoner interrogations revealed that the area was the base for the PAVN 271st Regiment, 9th Division and other support units.[2]: 48

The Crow's Nest – Operation Cuu Long/SD9/06

On 20 April, elements of the ARVN 9th Infantry Division attacked 6 km (3.7 mi) into Cambodia west of the "Crow's Nest" in Operation Cuu Long/SD9/06. The ARVN claimed 187 PAVN/VC killed and over 1,000 weapons captured for a cost of 24 killed. Thirty CH-47 sorties were flown to remove captured weapons and ammunition before it was decided to destroy the remainder in situ. The ARVN force returned to South Vietnam on 23 April.[2]: 48–49

On 28 April, Kien Tuong Province Regional Forces with support from the 9th Division attacked 3 km (1.9 mi) into the "Crow's Nest" again in a two-day operation, reportedly killing 43 PAVN/VC and capturing two for the loss of two killed.[2]: 49 During the same period the Regional Forces also raided northwest of Kampong Rou District killing 43 PAVN/VC and capturing 88 for the loss of 2 killed.[2]: 49–50

On 27 April, an ARVN Ranger battalion advanced into Kandal Province to destroy a PAVN/VC base. Four days later other South Vietnamese troops drove 16 kilometers into Cambodian territory. On 20 April, 2,000 ARVN troops advanced into the Parrot's Beak, killing 144 PAVN troops.[5]: 149 On 22 April, Nixon authorized American air support for the South Vietnamese operations. All of these incursions into Cambodian territory were simply reconnaissance missions in preparation for a larger-scale effort being planned by MACV and its ARVN counterparts, subject to authorization by Nixon.[5]: 152

The Parrot's Beak – Operation Toan Thang 42

On 30 April ARVN forces launched Operation Toan Thang 42 (Total Victory), also labeled Operation Rock Crusher. Twelve ARVN battalions of approximately 8,700 troops (two armored cavalry squadrons from III Corps and two from the 25th and 5th Infantry Divisions, an infantry regiment from the 25th Infantry Division, and three Ranger battalions and an attached ARVN Armored Cavalry Regiment from the 3rd Ranger Group) crossed into the Parrot's Beak region of Svay Rieng Province.[2]: 51–55

The offensive was under the command of Lieutenant General Đỗ Cao Trí, the commander of III Corps, who had a reputation as one of the most aggressive and competent ARVN generals. Tri's operation was to have begun on the 29th but Trí refused to budge, claiming that his astrologer had told him "the heavens were not auspicious".[1]: 53 During their first two days in Cambodia, ARVN units had several sharp encounters with PAVN forces losing 16 killed while killing 84 PAVN and capturing 65 weapons.[2]: 56 The PAVN, forewarned by previous ARVN incursions, however, conducted only delaying actions in order to allow the bulk of their forces to escape to the west.[5]: 172 [2]: 56

Phase II of the operation began with the arrival of elements of IV Corps, consisting of the 9th Infantry Division, five armored cavalry squadrons and one Ranger group. Four tank-infantry task forces attacked into the Parrot's Beak from the south. After three days of operations, ARVN claimed 1,010 PAVN troops had been killed and 204 prisoners taken for the loss of 66 ARVN dead.[1]: 54 On 3 May the III Corps and IV Corps units linked up and searched the area for supply caches.[2]: 57–58

Phase III began on 7 May with one ARVN task force engaging the PAVN 10 km (6.2 mi) north of Prasot killing 182 and capturing 8, while another task force found a 200-bed hospital. On 9 May the two task forces linked up southwest of Kampong Trach, crossed the Kompong Spean River and searched the area for supply caches until 11 May.[2]: 60–62

On 11 May Thiệu and Kỳ visited ARVN units in the field and Thiệu ordered III Corps to clear Route 1 and be prepared to relieve Kampong Trach in order to facilitate the evacuation of Vietnamese civilians from Phnom Penh. On 13 May Trí launched Phase IV, moving all three III Corps task forces west along Route 1 from Svay Rieng to meet up with IV Corps forces at Kampong Trabaek. To replace the departing units, Tây Ninh Province Regional Force units were moved into the area. On 14 May the task forces killed 74 PAVN/VC and captured 76. On 21 May a task force killed 9 PAVN and captured 26 from the PAVN 27th Regiment, 9th Division. By 22 May Route 1 was considered secured.[2]: 62–64

On 23 May III Corps began Phase V to relieve Kampong Cham, headquarters of FANK's Military Region I, which had been under siege by the PAVN 9th Division, which had occupied the 180-acre (0.73 km2) Chup rubber plantation northeast of the city and had begun bombarding the city from there. Two task forces moved along Routes 7 from Krek and 15 from Prey Veng to converge on the Chup plantation. The ARVN 7th Airborne Battalion engaged PAVN forces outside of Krek killing 26 and capturing 16. On 25 May armored and Ranger units clashed with the PAVN south of Route 7. On 28 May one task force engaged a PAVN unit killing 73 while the other task force located various supply caches. As the task forces converged on the Chup plantation heavy fighting began which continued until 1 June.[2]: 65–68 [5]: 177

Meanwhile, on 25 May Tây Ninh Province RF units and CIDG forces engaged PAVN/VC forces in the Angel's Wing area killing 38 and capturing 21. On 29 May a task force was sent to assist in the Angel's Wing area. PAVN/VC anti-aircraft fire was particularly heavy, downing one RVNAF A-1H, one USAF F-100 Super Sabre and one U.S. Army AH-1 Cobra gunship.[2]: 67

On 3 June the ARVN began rotating units for rest and refit, withdrawing from around Kampong Cham to Krek. The PAVN quickly moved back into the area and renewed their siege of the city. On 19 June Thiệu ordered III Corps to relieve Kampong Cham once again and on 21 June three task forces moved towards Chup along Route 7 from Krek. By 27 June the PAVN had left the Chup area. On 29 June Task Force 318 was engaged by a PAVN force on Route 15 and the ARVN killed 165 PAVN for losses of 34 killed and 24 missing.[2]: 68–69

Results for the operation were 3,588 PAVN/VC killed or captured and 1,891 individual and 478 crew-served weapons captured.[2]: 82

The Fishhook – Operations Toan Thang 43-6/Rock Crusher

On 1 May an even larger operation, in parallel with Toan Thang 42, known by the ARVN as Operation Toan Thang 43 and by MACV as Operation Rock Crusher, got underway as 36 B-52s dropped 774 tons of bombs along the southern edge of the Fishhook. This was followed by an hour of massed artillery fire and another hour of strikes by tactical fighter-bombers. At 10:00, the 1st Cavalry Division, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment (11th ACR), the ARVN 1st Armored Cavalry Regiment and the ARVN 3rd Airborne Brigade then entered Kampong Cham Province. Known as Task Force Shoemaker (after General Robert M. Shoemaker, the Assistant Division Commander of the 1st Cavalry Division), the force attacked the PAVN/VC stronghold with 10,000 U.S. and 5,000 South Vietnamese troops. The operation utilized mechanized infantry and armored units to drive deep into the province where they would then link up with ARVN airborne and U.S. airmobile units that had been lifted in by helicopter.[5]: 164 [2]: 70–73

Opposition to the incursion was expected to be heavy, but PAVN/VC forces had begun moving westward two days before the advance began. By 3 May, MACV reported only eight Americans killed and 32 wounded, low casualties for such a large operation.[5]: 164 There was only scattered and sporadic contact with delaying forces such as that experienced by elements of the 11th ACR three kilometers inside Cambodia. PAVN troops opened fire with small arms and rockets only to be blasted by tank fire and tactical airstrikes. When the smoke had cleared, 50 dead PAVN soldiers were counted on the battlefield while only two U.S. troops were killed during the action.[5]: 164 [21]

The North Vietnamese had ample notice of the impending attack. A 17 March directive from the headquarters of the B-3 Front, captured during the incursion, ordered PAVN/VC forces to "break away and avoid shooting back...Our purpose is to conserve forces as much as we can".[19]: 203 The only surprised party amongst the participants in the incursion seemed to be Lon Nol, who had been informed by neither Washington nor Saigon concerning the impending invasion of his country. He only discovered the fact after a telephone conversation with the U.S. Ambassador, who had found out about it himself from a radio broadcast.[10]: 608

The only conventional battle fought by American troops occurred on 1 May at Snuol, the terminus of the Sihanouk Trail at the junction of Routes 7, 13 and 131. Elements of the 11th ACR and supporting helicopters came under PAVN fire while approaching the town and its airfield. When a massed American attack was met by heavy resistance, the Americans backed off, called in air support and blasted the town for two days, reducing it to rubble. During the action, Brigadier general Donn A. Starry, commander of the 11th ACR, was wounded by grenade fragments and evacuated.[22]

On the following day, Company C, 1st Battalion (Airmobile), 5th Cavalry Regiment, entered what came to be known as "The City", southwest of Snoul. The two-square mile PAVN complex contained over 400 thatched huts, storage sheds, and bunkers, each of which was packed with food, weapons and ammunition. There were truck repair facilities, hospitals, a lumber yard, 18 mess halls, a pig farm and even a swimming pool.[5]: 167

The one thing that was not found was COSVN. On 1 May a tape of Nixon's announcement of the incursion was played for Abrams, who according to Lewis Sorley "must have cringed" when he heard the President state that the capture of the headquarters was one of the major objectives of the operation.[19]: 203

MACV intelligence knew that the mobile and widely dispersed headquarters would be difficult to locate. In response to a White House query before the fact, MACV had replied that "major COSVN elements are dispersed over approximately 110 square kilometers of jungle" and that "the feasibility of capturing major elements appears remote".[19]: 203

After the first week of operations, additional battalion and brigade units were committed to the operation, so that between 6 and 24 May, a total of 90,000 Allied troops (including 33 U.S. maneuver battalions) were conducting operations inside Cambodia.[1]: 158 Due to increasing political and domestic turbulence in the U.S., Nixon issued a directive on 7 May limiting the distance and duration of U.S. operations to a depth of 30 kilometers (19 mi) and setting a deadline of 30 June for the withdrawal of all U.S. forces to South Vietnam.[5]: 168 The final results for the operation were 3,190 PAVN/VC killed or captured and 4,693 individual and 731 crew-served weapons captured.[2]: 82

Operations Toan Thang 44, 45 and 46

On 6 May the U.S. 1st and 2nd Brigades, 25th Infantry Division, launched Operation Toan Thang 44 against Base Areas 353, 354 and 707 located north and northeast of Tây Ninh Province. Once again, a hunt for COSVN units was conducted, this time around the Cambodian town of Memot and, once again, the search was futile. On 7 May the 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment engaged a PAVN force killing 167 and capturing 28 weapons. On 11 May brigade units found a large food and material cache. The operation ended on 14 May.[2]: 78–79 Results for the operation were 302 PAVN/VC killed or captured and 297 individual and 34 crew-served weapons captured.[2]: 82 Another source states that the division killed 1,017 PAVN/VC troops while losing 119 of its own men killed.[1]: 126

Simultaneous with the launching of Toan Thang 44, two battalions of the U.S. 3rd Brigade, 9th Infantry Division, crossed the border 48 kilometers southwest of the Fishhook into an area known as the "Dog's Face" from 7 through 12 May. The only significant contact with PAVN forces took place near Chantrea District, where 51 PAVN were killed and another 21 were captured. During the operation, the brigade lost eight men killed and 22 wounded.[22]: 272

On 6 May the 2nd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, launched Operation Toan Thang 45 against Base Area 351 northwest of Bù Đốp District. On 7 May the Cavalry located a massive supply cache, nicknamed "Rock Island East" after the U.S. Army's Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois, the area contained more than 6.5 million rounds of anti-aircraft ammunition, 500,000 rifle rounds, thousands of rockets, several General Motors trucks, and large quantities of communications equipment.[5]: 167

A pioneer road was constructed to aid the evacuation of the captured weaponry. On 12 May the 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, was attacked overnight by a PAVN force losing one killed while claiming 50 PAVN killed. The Cavalry continued searching for supply caches until returning to South Vietnam on 29 June.[2]: 79–81 Results for the operation were 1,527 PAVN/VC killed or captured and 3,073 individual and 449 crew-served weapons captured.[2]: 82

Also on 6 May the ARVN 9th Regiment, 5th Infantry Division, launched Operation Toan Thang 46 against Base Area 350. On 25 May, after being engaged by a PAVN/VC force, the 9th Regiment discovered a 500-bed hospital. The Regiment continued searching for supply caches before starting a withdrawal towards Route 13 on 20 June, returning to South Vietnam on 30 June.[2]: 81–82 Results for the operation were 79 PAVN/VC killed or captured and 325 individual and 41 crew-served weapons captured.[2]: 82

Operations Binh Tay I–III

In the II Corps area, Operation Binh Tay I (Operation Tame the West) was launched by the 1st and 2nd Brigades of the U.S. 4th Infantry Division and the ARVN 40th Infantry Regiment, 22nd Infantry Division against Base Area 702 (the traditional headquarters of the PAVN B3 Front) in northeastern Cambodia from 5–25 May. Following airstrikes, the initial American forces, the 3rd Battalion, 506th Infantry (on loan from the 101st Airborne Division), assaulting via helicopter, were driven back by intense anti-aircraft fire. On 6 May following preparatory airstrikes the assault was resumed. Helicopters carrying the 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry were met again by intense anti-aircraft fire and were diverted to an alternative landing zone, however only 60 men were landed before intense PAVN fire (which shot down one helicopter and damaged two others) shut down the landing zone, leaving them stranded and surrounded overnight.[22]: 195 [2]: 93–94

On 7 May, the division's 2nd Brigade inserted its three battalions unopposed. On 10 May, Bravo Company, 3/506th Infantry, was ambushed by a much larger PAVN force in the Se San Valley. Eight U.S. soldiers were killed and 28 wounded, among those killed was Specialist Leslie Sabo, Jr. (posthumously promoted to Sergeant), who was recommended for the Medal of Honor, but the paperwork went missing until 1999.[23] Sabo was awarded the Medal of Honor on 16 May 2012 by President Barack Obama.[24][25]

After ten days the American troops returned to South Vietnam, leaving the area to the ARVN.[22]: 201 Historian Shelby Stanton has noted that "there was a noted lack of aggressiveness" in the combat assault and that the division seemed to be "suffering from almost total combat paralysis."[18]: 324 The operation ended on 25 May, U.S./ARVN losses were 43 killed while PAVN/VC losses were 212 killed and seven captured and 859 individual and 20 crew-served weapons captured.[2]: 94

During Operation Binh Tay II, the ARVN 22nd Division moved against Base Area 701 and B3 Front units such as the 24th, 28th or 66th Regiments and the 40th Artillery Regiment from 14 to 27 May. No significant combat occurred but the ARVN killed 73 PAVN/VC and captured six and located supply caches containing 346 individual and 23 crew-served weapons, ammunition and medical supplies. The operation ended on 27 May.[2]: 95–97

Operation Binh Tay III, was carried out by ARVN forces between 20 May and 27 June when elements of the ARVN 23rd Division conducted operations against Base Area 740.[26][27][2]: 97–100 During Phase 1 from 20 May to 3 June the ARVN killed 96 PAVN/VC and captured one while losing 29 killed.[2]: 97–99 Phase 2 took place from 4 to 12 June with limited results. During Phase 3 from 19 to 27 June and resulted the ARVN killed 149 PAVN/VC and captured 3 and 581 individual and 85 crew-served weapons for the loss of 38 killed.[2]: 99–100

Operations Cuu Long I–III

On 9 May ARVN IV Corps launched Operation Cuu Long, in which ARVN ground forces, including mechanized and armored units, drove west and northwest up the eastern side of the Mekong River from 9 May to 1 July. A combined force of 110 Republic of Vietnam Navy and 30 U.S. vessels proceeded up the Mekong to Prey Veng, permitting IV Corps ground forces to move westward to Phnom Penh to aid ethnic Vietnamese seeking flight to South Vietnam. During these operations South Vietnamese and American naval forces evacuated about 35,000 Vietnamese from Cambodia.[1]: 146 Those who did not wish to be repatriated were then forcibly expelled.[5]: 174

Surprisingly, North Vietnamese forces did not oppose the evacuation, though they could easily have done so.[5]: 174 It was already too late for thousands of ethnic Vietnamese murdered by Cambodian persecution, but there were tens of thousands of Vietnamese still within the country who could be evacuated to safety. Thiệu arranged with Lon Nol to repatriate as many as were willing to leave. The new relationship did not, however, prevent the Cambodian government from stripping the Vietnamese of their homes and other personal property before they left.[5]: 174 [2]: 83–85

Subsequent operations conducted by IV Corps included Operation Cuu Long II (16–24 May), which continued actions along the western side of the Mekong. Lon Nol had requested that the ARVN help in the retaking of Kampong Speu, a town along Route 4 southwest of Phnom Penh and 90 miles (140 km) inside Cambodia. A 4,000-man ARVN armored task force linked up with FANK troops and then retook the town. Operation Cuu Long III (24 May – 30 June) was an evolution of the previous operations after U.S. forces had left Cambodia.[5]: 177

Operation Cuu Long II was initiated by IV Corps on 16 May to assist the FANK in restoring security around Takéo. ARVN forces committed included the 9th and 21st Infantry Divisions, 4th Armor Brigade, 4th Ranger Group and the Châu Đốc Province Regional Forces. The weeklong operation resulted in 613 PAVN/VC killed and 52 captured and 792 individual and 84 crew-served weapons captured. ARVN losses were 36 killed.[2]: 88–89 Operations continued under the name Operation Cuu Long III starting 25 May in the same area with the same forces less the 21st Division which had returned to South Vietnam. While the PAVN/VC generally avoided contact, the ARVN located 3,500 weapons in a storage area.[2]: 89

Evacuation of Ratanakiri – Operation Binh Tay IV

In late June the FANK asked the U.S. and South Vietnam for assistance in evacuating two isolated garrisons at Ba Kev and Labang Siek in Ratanakiri Province. On 21 June the ARVN 22nd Division was given the mission of facilitating the evacuation of the bases. On 23 June the division moved to Đức Cơ Camp and was organized into four task forces which would then advance west along Route 19 to Ba Kev, protected by U.S. air cavalry units.[2]: 100–105

The FANK units at Labang Siek would then move 35 km (22 mi) east along Route 19 to Ba Kev and would then be flown or trucked to Đức Cơ across the border to South Vietnam. The operation began on 25 June and was successfully completed by 27 June with 7,571 FANK troops, their dependents and refugees evacuated. ARVN losses were 2 killed while PAVN losses were 6 killed and 2 weapons captured.[2]: 100–105

Air support and logistics

Aerial operations for the incursion got off to a slow start. Reconnaissance flights over the operational area were restricted since MACV believed that they might serve as a signal of intention. The role of the United States Air Force (USAF) in the planning for the incursion itself was minimal at best, in part to preserve the secrecy of Menu which was then considered an overture to the thrust across the border.[28]

On 17 April, Abrams requested that Nixon approve Operation Patio, covert tactical airstrikes in support of MACV-SOG reconnaissance elements in Cambodia. This authorization was given, allowing U.S. aircraft to penetrate 13 miles (21 km) into northeastern Cambodia. This boundary was extended to 29 miles (47 km) along the entire frontier on 25 April. Patio was terminated on 18 May after 156 sorties had been flown.[29] The last Menu mission was flown on 26 May.[30]

During the incursion itself, U.S. and ARVN ground units were supported by 9,878 aerial sorties (6,012 USAF/2,966 RVNAF), an average of 210 per day.[1]: 141 During operations in the Fishhook, for example, the USAF flew 3,047 sorties and the RVNAF 332.[1]: 75 These tactical airstrikes were supplemented by 653 B-52 missions in the border regions (71 supporting Binh Tay operations, 559 for Toan Thang operations and 23 for Cuu Long).[1]: 143

30 May saw the inauguration of Operation Freedom Deal (named as of 6 June), a continuous U.S. aerial interdiction campaign conducted in Cambodia. These missions were limited to a depth of 48 kilometers between the South Vietnamese border and the Mekong River.[9]: 201 Within two months, however, the limit of the operational area was extended past the Mekong and U.S. tactical aircraft were soon directly supporting Cambodian forces in the field.[9]: 199 These missions were officially denied by the U.S. and false coordinates were given in official reports to hide their existence.[29]: 148 Defense Department records indicated that out of more than 8,000 combat sorties flown in Cambodia between July 1970 and February 1971, approximately 40 percent were flown outside the authorized boundary.[29]: 148

The real struggle for the U.S. and ARVN forces in Cambodia was the effort at keeping their units supplied. Once again, the need for security before the operations and the rapidity with which units were transferred to the border regions precluded detailed planning and preparation. Abrams was fortunate, had the PAVN/VC fought for the sanctuaries instead of fleeing, U.S. and ARVN units would have rapidly consumed their available supplies.[1]: 136 This situation was exacerbated by the poor road network in the border regions and the possibility of ambush for nighttime road convoys demanded that deliveries only take place during daylight.[1]: 135

The tempo of logistical troops could be mind numbing. The U.S. Third Ordnance Battalion for example, loaded up to 150 flatbed trucks per day with ammunition. Logisticians were issuing more than 2,300 short tons (almost five million pounds) of supplies every day to support the incursion.[1]: 135 Aerial resupply, therefore, became the chief method of logistical replenishment for the forward units. Military engineers and aviators were kept in constant motion throughout the incursion zone.[1]: 96–101

Due to the rapid pace of operations, deployment, and redeployment, coordination of artillery units and their fires became a worrisome quandary during the operations.[1]: 72–73 This was made even more problematic by the confusion generated by the lack of adequate communications systems between the rapidly advancing units. The joint nature of the operation added another level of complexity to the already overstretched communications network.[1]: 149–151 Regardless, due to the ability of U.S. logisticians to innovate and improvise, supplies of food, water, ammunition, and spare parts arrived at their destinations without any shortages hampering combat operations and the communications system, although complicated, functioned well enough during the short duration of U.S. operations.[citation needed]

Aftermath

The North Vietnamese response to the incursion was to avoid contact with allied forces and, if possible, to fall back westward and regroup. PAVN/VC forces were well aware of the planned attack and many COSVN/B-3 Front military units were already far to the north and west conducting operations against the Cambodians when the offensive began.[1]: 45 During 1969 PAVN logistical units had already begun the largest expansion of the Ho Chi Minh trail conducted during the entire conflict.[31]

As a response to the loss of their Cambodian supply route, PAVN forces seized the Laotian towns of Attopeu and Saravane during the year, pushing what had been a 60-mile (97 km) corridor to a width of 90 miles (140 km) and opening the entire length of the Kong River system into Cambodia.[31] A new logistical command, the 470th Transportation Group, was created to handle logistics in Cambodia and the new "Liberation Route" ran through Siem Pang and reached the Mekong at Stung Treng.[6]: 257

The majority of the PAVN/VC forces had withdrawn deeper into Cambodia before the invasion with a rearguard left to stage a fighting retreat to avoid charges of cowardice. PAVN/VC losses in manpower were minimal, but much equipment and arms were abandoned.[10]: 610 The allied forces captured a vast haul of weapons and equipment and the for the rest of 1970 PAVN/VC activities in the Saigon area were notably reduced.[10]: 610 However, by 1971 all of the weapons and equipment had been replaced while the PAVN/VC returned to their frontier bases in the summer of 1970 after the withdraw of the Americans in June 1970.[10]: 610

Abrams was frustrated with the invasion, saying: "We need to go west from where we are, we need to go north and east from where we are. And we need to do it now. It's moving and-goddam, goddam".[11]: 568 When one officer asked "Time to exploit?", Abrams replied: "Christ! It's so clear. Don't let them pick up the pieces. Don't let them pick up the pieces. Just like the Germans. You give them 36 hours and, goddam it, you've got to start the war all over again".[11]: 568

As foreseen by Laird, fallout from the incursion was quick in coming on the campuses of America's universities, as protests erupted against what was perceived as an expansion of the conflict into yet another country. On 4 May the unrest escalated to violence when Ohio National Guardsmen shot and killed four unarmed students (two of whom were not protesters) during the Kent State shootings. Two days later, at the University at Buffalo, police wounded four more demonstrators. On 15 May city and state police killed two and wounded twelve at Jackson State College in Jackson, Mississippi.[32]

Earlier, on 8 May 100,000 protesters had gathered in Washington and another 150,000 in San Francisco on only ten days notice.[32] Nationwide, 30 ROTC buildings went up in flames or were bombed while 26 schools witnessed violent clashes between students and police. National Guard units were mobilized on 21 campuses in 16 states.[32] The student strike spread nationwide, involving more than four million students and 450 universities, colleges and high schools in mostly peaceful protests and walkouts.[5]: 178–179

Simultaneously, public opinion polls during the second week of May showed that 50 percent of the American public approved of Nixon's actions.[5]: 182 Fifty-eight percent blamed the students for what had occurred at Kent State. On both sides, emotions ran high. In one instance, in New York City on 8 May, pro-administration construction workers rioted and attacked demonstrating students. Such violence, however, was an aberration. Most demonstrations, both pro- and anti-war, were peaceful. On 20 May 100,000 construction workers, tradesmen, and office workers marched peacefully through New York City in support of Nixon's policies.[5]: 182

Reaction in the U.S. Congress to the incursion was also swift. Senators Frank F. Church (Democratic Party, Idaho) and John S. Cooper (Republican Party, Kentucky), proposed an amendment to the Foreign Military Sales Act of 1971 that would have cut off funding not only for U.S. ground operations and advisors in Cambodia, but would also have ended U.S. air support for Cambodian forces.[33] On 30 June the U.S. Senate passed the act with the amendment included. The bill was defeated in the House of Representatives after U.S. forces were withdrawn from Cambodia as scheduled. The newly amended act did, however, rescind the Southeast Asia Resolution (better known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution) under which Presidents Johnson and Nixon had conducted military operations for seven years without a declaration of war.[19]: 212–213

The Cooper–Church Amendment was resurrected during the winter and incorporated into the Supplementary Foreign Assistance Act of 1970. This time the measure made it through both houses of Congress and became law on 22 December. As a result, all U.S. ground troops and advisors were barred from participating in military actions in Laos or Cambodia, while the air war being conducted in both countries by the USAF was ignored.[9]: 276

In June 1970 Thiệu met with Lon Nol, Prince Sirik Matak and Cheng Heng at Neak Loeung where the ARVN had established an operational base.[2]: 158 On 27 June 1970 Thiệu gave a televised speech in which he outlined South Vietnam's Cambodia policy: (1) South Vietnamese forces would continue to operate on Cambodian territory after the withdrawal of U.S. forces to prevent the PAVN/VC from returning to their base areas; (2) South Vietnamese forces would continue to evacuate Vietnamese who wished to be repatriated; (3) The South Vietnamese government would support the Cambodian government in meeting PAVN/VC aggression; (4) future activities in Cambodia would be conducted without U.S. support; (5) the bulk of South Vietnamese forces would be withdrawn from Cambodia; and (6) the object of South Vietnamese actions was to improve South Vietnamese security and ensure the success of Vietnamization.[2]: 125 The South Vietnamese military established a liaison office in Phnom Penh and monthly meetings of the JGS, FANK command and MACV were instituted.[2]: 158

South Vietnamese operations into the border areas of Cambodia continued. Operation Toan Thang 42 Phase VI was conducted along Routes 1 and 7 with limited success due to the onset of the rainy season.[2]: 127–129 Operation Cuu Long 44-02 was conducted from 13 to 25 January 1971 to reopen Route 4 which had been closed by the PAVN 1st Division occupying the Pich Nil Pass (11°11′42″N 104°04′26″E / 11.195°N 104.074°E). The operation was successful with PAVN/Khmer Rouge losses of 211 killed while ARVN losses were 16 killed.[2]: 129–131 [34]: 197–198

In mid-1971 the Cambodian government requested the abrogation of South Vietnam's zone of operations in Cambodia and the South Vietnamese agreed to reducing the zone to a depth of 10–15 km (6.2–9.3 mi), which reflected the inability of the South Vietnamese to conduct deeper incursions without U.S. support.[2]: 126 South Vietnam mounted its last major operation in Cambodia from 27 March to 2 April 1974 culminating in the Battle of Svay Rieng. Following that action the severe constraints on ARVN ammunition expenditures, fuel usage, and flying hours permitted no new initiatives.[35]

Conclusion

Nixon proclaimed the incursion to be "the most successful military operation of the entire war."[1]: 153 Abrams was of like mind, believing that time had been bought for the pacification of the South Vietnamese countryside and that U.S. and ARVN forces had been made safe from any attack out of Cambodia during 1971 and 1972. A "decent interval" had been obtained for the final American withdrawal. ARVN General Tran Dinh Tho was more skeptical:

[D]espite its spectacular results...it must be recognized that the Cambodian incursion proved, in the long run, to pose little more than a temporary disruption of North Vietnam's march toward domination of all of Laos, Cambodia and South Vietnam.[2]

John Shaw and other historians, military and civilian, have based the conclusions of their work on the incursion on the premise that the North Vietnamese logistical system in Cambodia had been so badly damaged that it was rendered ineffective.[1]: 161–170 [18]: 324–325 [36] However this was only temporary as shown by the sustained PAVN attacks on An Loc supported out of Cambodia during the 1972 Easter Offensive.[37]

The U.S. and ARVN claimed 11,369 PAVN/VC soldiers killed and 2,509 captured. The logistical haul discovered, removed, or destroyed in eastern Cambodia during the operations was indeed prodigious: 22,892 individual and 2,509 crew-served weapons; 7,000 to 8,000 tons of rice; 1,800 tons of ammunition (including 143,000 mortar shells, rockets and recoilless rifle rounds); 29 tons of communications equipment; 431 vehicles; and 55 tons of medical supplies.[1]: 162 [2]: 193 MACV intelligence estimated that PAVN/VC forces in southern Vietnam required 1,222 tons of all supplies each month to keep up a normal pace of operations.[1]: 163

The official PAVN history claims that from April to July they eliminated 40,000 enemy troops, destroyed 3,000 vehicles and 400 artillery pieces and captured 5,000 weapons, 113 vehicles, 1,570 tons of rice and 100 tons of medical supplies.[6]: 256

Due to the loss of its Cambodian supply system and continued aerial interdiction in Laos, MACV estimated that for every 2.5 tons of materiel sent south down the Ho Chi Minh trail, only one ton reached its destination. However, the true loss rate was probably only around ten percent. Due to lack of verifiable sources in North Vietnam, this figure is, at best, an estimate. The official PAVN history noted:

[T]he enemy had established control over and successfully suppressed, to some extent at least, our nighttime supply operations. Enemy aircraft destroyed 4,000 trucks during the 1970–1971 dry season... Our supply effort, conducted during a single season of the year and using a single supply route, was unable to keep up with our requirements and our night supply operations encountered difficulties.[6]: 262–263

Regardless, the PAVN's Group 559 successfully countered these efforts through camouflage tactics and the construction of thousands of kilometers of "bypass" roads to avoid choke points that frequently came under enemy attack. Per the same history,

[I]n 1969 Group 559 shipped 20 thousand tons of supplies to the battlefields, in 1970 this total rose to 40 thousand tons and in 1971 it increased to 60 thousand tons... losses along the way in 1969, which were 13.5 percent, declined to 3.4 percent in 1970 and 2.7 percent in 1971.[6]: 262–263

The USAF's best estimate for the same time period was that one-third of the total amount was destroyed in transit.[38]

South Vietnamese forces had performed well during the incursion but their leadership was uneven. Trí proved a resourceful and inspiring commander, earning the sobriquet the "Patton of the Parrot's Beak" from the American media. Abrams also praised the skill of General Nguyễn Viết Thanh, commander of IV Corps and planner of the Parrot's Beak operation.[19]: 221 Unfortunately for the South Vietnamese, both officers were killed in helicopter crashes, Thanh on 2 May in Cambodia and Trí in February 1971. Other ARVN commanders, however, had not performed as well. Even at this late date in the conflict, the appointment of ARVN general officers was prompted by political loyalty rather than professional competence.[18]: 337

As a test of Vietnamization, the incursion was praised by American generals and politicians alike, but the Vietnamese had not really performed alone. The participation of U.S. ground and air forces had precluded any such claim. When called on to conduct solo offensive operations during the incursion into Laos (Operation Lam Son 719) in 1971, the ARVN's continued weaknesses would become all too apparent.[18]: 337

The Cambodian government was not informed of the incursion until it was already under way. The Cambodian leadership however welcomed the intervention against PAVN bases and the resulting weakening of PAVN military capabilities. The leadership had hoped for permanent U.S. occupation of the PAVN sanctuaries because FANK and ARVN forces were unable to fill the vacuum in these territories following U.S. withdrawal and instead the PAVN and Khmer Rouge moved quickly to fill the void.[16]: 173–174 It has been argued that the incursion heated up the civil war and helped the insurgent Khmer Rouge gather recruits to their cause.[2]: 166–167 [16]: 173–174 [39]

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Shaw, John (2005). The Cambodian Campaign: The 1970 Offensive and America's Vietnam War. University of Kansas Press. ISBN 9780700614059.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Tran, Dinh Tho (1979). The Cambodian Incursion (PDF). United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 9781981025251. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Currey, Cecil (1997). Victory at Any Cost: The Genius of Viet Nam's Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap. Potomac Books. p. 278. ISBN 9781574887426.

- ^ a b c Isaacs, Arnold; Hardy, Gordon (1987). The Vietnam Experience Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. Boston Publishing Company. p. 54. ISBN 9780939526246.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Lipsman, Samuel; Doyle, Edward (1983). The Vietnam Experience Fighting for Time. Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0939526079.

- ^ a b c d e Military History Institute of Vietnam (2002). Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975. trans. Pribbenow, Merle. University of Kansas Press. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- ^ a b c Deac, Wilfred (1987). Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970–1975. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781585440542.

- ^ Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Command History 1967, Annex F, Saigon, 1968, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nalty, Bernard C. Nalty (1997). Air War Over South Vietnam, 1968–1975 (PDF). Air Force History and Museums Program. ISBN 9780160509148.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Karnow, Stanley (1983). Vietnam A History. Viking. ISBN 0140265473.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an Langguth, A.J. (2000). Our Vietnam The War 1954–1975. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743212312.

- ^ Chandler, David (1991). The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution since 1945. Yale University Press. p. 231. ISBN 9780300057522.

- ^ Chan, Sucheng (2004). Survivors: Cambodian Refugees in the United States. University of Illinois Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780252071799.

- ^ Heo, Uk (2007). DeRouen, Karl R. (ed.). Civil Wars of the World: Major Conflicts Since World War II, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 222. ISBN 9781851099191.

- ^ Gilster, Herman (1993). The Air War in Southeast Asia: Case Studies of Selected Campaigns. Air University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9781782666554.

- ^ a b c d Sak, Sutsakhan (1984). The Khmer Republic at war and the final collapse. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 9781780392585.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Dmitry Mosyakov, "The Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese Communists: A History of Their Relations as Told in the Soviet Archives", in Susan E. Cook, ed., Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda (Yale Genocide Studies Program Monograph Series No. 1, 2004), pp. 54ff. Available online at: www.yale.edu/gsp/publications/Mosyakov.doc "In April–May 1970, many North Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in response to the call for help addressed to Vietnam not by Pol Pot, but by his deputy Nuon Chea. Nguyen Co Thach recalls: "Nuon Chea has asked for help and we have liberated five provinces of Cambodia in ten days.""

- ^ a b c d e Stanton, Shelby (1985). The Rise and Fall of an American Army: U.S. Ground Forces in Vietnam, 1963–1973. Dell. ISBN 9780891418276.

- ^ a b c d e f Sorley, Lewis (1999). A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam. Harvest Books. ISBN 9780156013093.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tảng, Truong Như; Chanoff, David (1985). A Vietcong memoir. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 177. ISBN 978015193636-6.

- ^ Casey, Michael (1987). The Vietnam Experience: The Army at War. Boston Publishing Company. p. 137. ISBN 978-0939526239.

- ^ a b c d Nolan, Keith (1986). Into Cambodia. Presidio Press. pp. 147–161. ISBN 978-0891416739.

- ^ "Year of the track". Ellwood City Ledger. Retrieved 24 July 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Burke, Matthew (16 April 2012). "Vietnam veteran to be awarded Medal of Honor posthumously". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "President Obama to award Medal of Honor". whitehouse.gov. 16 April 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2018 – via National Archives.

- ^ Webb, Willard J. (2002). The Joint Chiefs of Staff and the War in Vietnam 1969–1970 (PDF). History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Washington, DC: Office of Joint History, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. p. 198.

- ^ Pitkin, Ian C. (2017). The Art of Limited Warfare: Operational Art in the 1970 Cambodian Campaign. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College. pp. 26–27. S2CID 158617136.

- ^ Schlight, John (1986). A War Too Long: The History of the USAF in Southeast Asia, 1961–1975 (PDF). Air Force History and Museums Program. pp. 183–184.

- ^ a b c Morocco, John (1988). The Vietnam Experience: Rain of Fire: Air War, 1968–1975. Boston Publishing Company. p. 146. ISBN 9780939526147.

- ^ Hartsook, Elizabeth; Slade, Stuart (2012). Air War Vietnam Plans and Operations 1969–1975. Lion Publications. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-9859730-9-4.

- ^ a b Prados, John (1998). The Blood Road: The Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietnam War. John Wiley and Sons. p. 191. ISBN 9780471254652.

- ^ a b c Gitlin, Todd (1987). The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. Bantam Books. p. 410. ISBN 9780553372120.

- ^ Fulghum, David; Maitland, Terrence (1984). The Vietnam Experience: South Vietnam on Trial: Mid-1970–1972. Boston Publishing Company. p. 9. ISBN 9780939526109.

- ^ Starry, Donn (1978). Mounted Combat in Vietnam. Vietnam Studies (PDF). Department of the Army. ISBN 9781517592288.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Le Gro, William (1985). Vietnam from ceasefire to capitulation (PDF). US Army Center of Military History. pp. 93–95. ISBN 9781410225429.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Palmer, Dave (1978). Summons of the Trumpet: U.S.-Vietnam in perspective. Presidio Press. pp. 300–301. ISBN 9780891410416.

- ^ Ngo, Quang Truong (1980). The Easter Offensive of 1972 (PDF). U.S. Army Center of Military History. pp. 130–135. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Nalty, Bernard (2005). The War Against Trucks: Aerial Interdiction in Southern Laos 1968–1972 (PDF). Air Force History and Museums Program. p. 297. ISBN 9781477550076.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Shawcross, William (1979). Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. Washington Square Books. ISBN 9780815412243.

Sources

- Vietnam, July 1970 – January 1972

- Vietnam, January 1969 – July 1970

- MACV Command History 1970 Volume III Archived 17 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine