Enterocyte

| Enterocyte | |

|---|---|

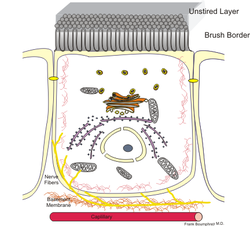

Schematic drawing of an enterocyte: the intestinal lumen is above the brush border. | |

| Details | |

| Location | Small intestine |

| Shape | Simple columnar |

| Function | Epithelial cells |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | enterocytus |

| MeSH | D020895 |

| TH | H3.04.03.0.00006 |

| FMA | 62122 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Enterocytes, or intestinal absorptive cells, are simple columnar epithelial cells which line the inner surface of the small and large intestines. A glycocalyx surface coat contains digestive enzymes. Microvilli on the apical surface increase its surface area. This facilitates transport of numerous small molecules into the enterocyte from the intestinal lumen. These include broken down proteins, fats, and sugars, as well as water, electrolytes, vitamins, and bile salts. Enterocytes also have an endocrine role, secreting hormones such as leptin.

Function

The major functions of enterocytes include:[1]

- Ion uptake, including sodium, calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, and copper. This typically occurs through active transport.

- Water uptake. This follows the osmotic gradient established by Na+/K+ ATPase on the basolateral surface. This can occur transcellularly or paracellularly.

- Sugar uptake. Polysaccharidases and disaccharidases in the glycocalyx break down large sugar molecules, which are then absorbed. Glucose crosses the apical membrane of the enterocyte using the sodium-glucose cotransporter. It moves through the cytosol (cytoplasm) and exits the enterocyte via the basolateral membrane (into the blood capillary) using GLUT2. Galactose uses the same transport system. Fructose, on the other hand, crosses the apical membrane of the enterocyte, using GLUT5. It is thought to cross into the blood capillary using one of the other GLUT transporters.

- Peptide and amino acid uptake. Peptidases in the glycocalyx cleave proteins to amino acids or small peptides. Enteropeptidase (also known as enterokinase) is responsible for activating pancreatic trypsinogen into trypsin, which activates other pancreatic zymogens. They are involved in the Krebs and the Cori Cycles and can be synthesized with lipase.

- Lipid uptake. Lipids are broken down by pancreatic lipase aided by bile, and then diffuse into the enterocytes. Smaller lipids are transported into intestinal capillaries, while larger lipids are processed by the Golgi and smooth endoplasmic reticulum into lipoprotein chylomicra and exocytozed into lacteals.

- Vitamin B12 uptake. Receptors bind to the vitamin B12-gastric intrinsic factor complex and are taken into the cell.

- Resorption of unconjugated bile salts. Bile that was released and not used in emulsification of lipids are reabsorbed in the ileum. Also known as the enterohepatic circulation.

- Secretion of immunoglobulins. Immunoglobulin A from plasma cells in the mucosa are absorbed through receptor-mediated endocytosis on the basolateral surface and released as a receptor-IgA complex into the intestinal lumen. The receptor component confers additional stability to the molecule.

Disorders

- Dietary fructose intolerance occurs when there is a deficiency in the amount of fructose carrier.

- Lactose intolerance is the most common problem of carbohydrate digestion and occurs when the human body doesn't produce a sufficient amount of lactase enzyme to break down the sugar lactose found in dairy. As a result of this deficiency, undigested lactose is not absorbed and is instead passed on to the colon. There bacteria metabolize the lactose and in doing so release gas and metabolic products that enhance colonic motility. This causes gas and other uncomfortable symptoms.

- Cholera toxin may increase the secretion or decrease the intake of water and electrolytes, leading to possibly severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.[2]

- Rotavirus selectively invades and kills mature enterocytes in the small intestine.[3]

Stem cell aging

Intestinal stem cell aging has been studied in Drosophila as a model for understanding the biology of stem cell/niche aging.[4] Using knockdown mutants defective in various genes that function in the DNA damage response in enterocytes, it was shown that deficiency in the DNA damage response accelerates intestinal stem cell aging, thus providing a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of this aging process.[4]

See also

References

- ^ Ross, M.H. & Pawlina, W. 2003. Histology: A Text and Atlas, 4th Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

- ^ Joaquín Sánchez, Jan Holmgren (February 2011). "Cholera toxin – A foe & a friend" (PDF). Indian Journal of Medical Research. 133: 158.

- ^ Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, Chapter 17, 749-819

- ^ a b Park JS, Jeon HJ, Pyo JH, Kim YS, Yoo MA. Deficiency in DNA damage response of enterocytes accelerates intestinal stem cell aging in Drosophila. Aging (Albany NY). 2018 Mar 7;10(3):322-338. doi: 10.18632/aging.101390. PMID 29514136; PMCID: PMC5892683

External links

- Histology image: 11706loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Digestive System: Alimentary Canal — jejunum, goblet cells and enterocytes"