English Avenue and Vine City

English Avenue and Vine City | |

|---|---|

Herndon Home, built by African-American insurance magnate Alonzo Herndon | |

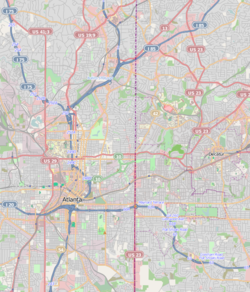

Location in Central Atlanta | |

| Coordinates: 33°45′48″N 84°24′37″W / 33.763441°N 84.410341°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Fulton |

| Government | |

| • Type | Neighborhoods of Atlanta |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

English Avenue and Vine City are two adjacent and closely linked neighborhoods of Atlanta, Georgia. Together the neighborhoods make up neighborhood planning unit L.[1] The two neighborhoods are frequently cited together in reference to shared problems and to shared redevelopment schemes and revitalization plans.[2][3][4][5]

English Avenue is bounded by the railroad line and the Marietta Street Artery neighborhood to the northeast, Northside Drive, the North Avenue railyards and downtown Atlanta to the east, Joseph E. Lowery Blvd. (formerly Ashby St.) and the Bankhead neighborhood to the west, and Joseph E. Boone Blvd. (called Simpson St. until 2008) and Vine City to the south. Its population was 3,309 in 2010.[6]

Vine City is bounded by Joseph E. Boone Blvd. (Simpson) and the English Avenue neighborhood to the north, Northside Drive and downtown Atlanta to the east, Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. (formerly Hunter St.) and the Atlanta University Center to the south, and Joseph E. Lowery Blvd. (Ashby) and the Washington Park neighborhood to the west. Its population was 2,785 in 2010.[6]

A section of the area, "The Bluff," is infamous throughout Metro Atlanta as a high crime area, but in late 2011, English Avenue and Vine City were the focus of multiple improvement plans, including a network of parks and trails,[2][7] increased police presence, and "rebranding" for a more positive image.[8][9][10] Construction is to start on the new Rodney Cook Sr. Park.

History

Development

What is now the English Avenue neighborhood was purchased in 1891 by son of Atlanta mayor James W. English, James W. English Jr., a hot-headed man[11] who earned income by subletting convict labor.[12] It was created as a white working-class neighborhood. Simpson Road was located along a residential race barrier with whites to the north and blacks to the south.[13] Today's English Avenue was known at different times as Bellwood[14] and as Western Heights. In 1910 the Western Heights school (later renamed Kingbery after a principal of the school, then renamed English Avenue Elementary School) was built at the northeast corner of English Ave. and Pelham St.[15]

Overcrowding in the neighborhood's school is documented as a serious issue from at least 1910 through 1946 (photo), notwithstanding multiple expansions of the facility.[16][17][18][19]

The area south of Simpson Road — today's Vine City — was settled at the end of the 1800s by large land owners, and a predominantly African-American residential area was established, though there were also white subdivisions, schools, and churches. A mix of social classes were present. In 1910 Alonzo F. Herndon, founder of the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, built his home at 587 University Place, now listed on the National Register and open to visitors.[20]

Racial tension and transition

The Great Atlanta fire of 1917 contributed to the already great need for housing for African Americans and by the 1920s-1940s, despite violence and bombings trying to prevent it, black residents started to move north across Simpson Road.[13]

In 1941, the Eagan Homes and Herndon Homes public housing projects opened and as a result, the black population in the area increased. On Hunter Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive), white business owners once lived behind their stores, but in the 1940s, black owners started taking over these businesses.[20] In 1947 Paschal's Restaurant, an Atlanta soul food landmark and meeting place for civil rights leaders, opened in its original location on West Hunter Street.[20] In 1951, the English Avenue Elementary School's designation was changed from white to black in response to most whites having moved out of the area.[21]

Heyday and Civil Rights

During the mid-20th century, the area was a middle-class African-American neighborhood.[22] Commercial areas included English Avenue; Simpson Street/Road, in its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s; and Bankhead Highway, which was part of the US Highway system, and was in its splendor in the 1960s. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. moved to the area in 1967, and his widow Coretta Scott King continued to live here until she moved to a Peachtree Road luxury condominium purchased for her by Oprah Winfrey in 2004.

In 1960, the English Avenue elementary school was dynamited, likely in retaliation for civil rights demonstrations by Black activists.[23] Mayor William B. Hartsfield condemned the dynamiting as the work of those from outside Atlanta, "the outhouse set".[21] The area experienced notable pro- and anti-Black Power riots in 1966[24] and 1967.[25]

Decline and crime

Suburbanization started draining the area's vitality starting in the 1970s.[13] Over the following decades, it attracted buyers and sellers of heroin, and deteriorated into a corner of poverty in the city, characterized by large numbers of abandoned, boarded-up houses.[22]

In 1995 the English Avenue Elementary School closed.[15]

In 2006, a "no-knock raid" in search of a drug dealer, burst into the home of Kathryn Johnston. Ms. Johnston, in her 80s, opened fire on the officers and wounded three and was killed by return fire from the officers. The incident resulted in much anger in the neighborhood and in close scrutiny of police use of "no-knock warrants" in drug raids.[26]

The 2008 tornado caused major damage in areas of Vine City (photos).

The 2010s foreclosure crisis hit the neighborhoods hard.[27] In April 2012, Creative Loafing reported that "on some streets more houses are boarded up than are lived in". Occupy Atlanta protested the Vine City foreclosure of Mrs. Pamela Flores by Bank of America.[28]

The desperate state of the area was described by reporter Thomas Wheatley in Creative Loafing in September 2012 as:[29]

"boarded-up homes built among the trees along the narrow streets,…people loitering in the middle of vacant lots, casting hollow stares at passing motorists, and…young men hanging out on street corners, hollering at passers-by and then to lookouts down the street"

Revitalization

1990s: Failed "empowerment zone"

In November 1994, the Atlanta Empowerment Zone was established, a 10-year, $250 million federal program to revitalize Atlanta's 34 poorest neighborhoods including the Bluff. Scathing reports from both the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Georgia Department of Community Affairs revealed corruption, waste, bureaucratic incompetence, and interference by mayor Bill Campbell.[30][31]

Replacement of public housing projects

As part of the Atlanta Housing Authority's systematic replacement of public housing projects by mixed-income communities (MIC), Eagan Homes was demolished and the Magnolia Park MIC replaced it. Herndon Homes was demolished in 2011.[32]

Historic Westside Village and Walmart

In 1999, the Atlanta Housing Authority first announced plans for the "Historic Westside Village", a $130 million commercial, residential and retail project at the area's southern end near Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. at Ashby St.[33] A Publix supermarket opened in May 2002[34] but the overall project stalled by 2003 as further anchor tenants did not materialize.[35] This, along with disappointing sales, caused the Publix - the only full-sized supermarket for miles around - to close in December 2009.[36] Creative Loafing called the project the most notorious "municipal boondoggle...to have tarred Atlanta" during mayor Bill Campbell's era; the project "fell victim to...cronyism, bureaucratic incompetence and a flagrant disregard for federal lending guidelines".[37] In December 2010 things looked up as the Atlanta Development Authority announced plans for Wal-Mart to open a store on the site, which Mayor Kasim Reed called "an end to the food desert in the area".[38][39] In January 2013 the Wal-Mart opened for business.[40][41]

Black-white coalition

The Christian Science Monitor reported that by 2008, businessman John Gordon and Rev. Anthony Motley, a 20-year resident of The Bluff, "Atlanta's roughest 'hood", had "formed a black-white coalition seeking angel investors" and brought together "local businesses, neighboring Georgia Tech, and church leaders to inspire not just city and private investment, but also to light a spark of hope among law-abiding residents – many of them older people fearful of the streets outside their front doors. Their unusual friendship" had "helped inspire two massive clean-up efforts, a small but significant drop in crime, and glimmers of fresh paint and clean-swept front walks."[42]

Rodney Cook Sr. Park

Cook Park is under construction by a partnership consisting of the City of Atlanta's Department of Watershed Management, The Trust for Public Land of Georgia, and the National Monuments Foundation. The park will consist of a system of storm water management including a retention pond similar to the one in nearby Historic Old Fourth Ward Park, walking trails and amenities including a terraced amphitheater and splash pad[43] and statues and monuments honoring a number of prominent Atlantans and Civil Rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Booker T. Washington.[44]

The site, located along the south side of Joseph E. Boone Boulevard, has been vacant for many years, after the city purchased several homes there that perpetually fell victim to severe flooding caused by historic mismanagement in the Proctor Creek watershed. In December 2011 Park Pride, a greenspace advocacy group, proposed a network of greenspaces and parks that—through the incorporation of green infrastructure—would help mitigate the recurring flooding from stormwater runoff that plagued the neighborhoods of Vine City and English Avenue for years.[2] In 2015, the City began cleaning the site, and the Trust For Public Land joined the partnership to plan, raise funds, and construct the park above and around the stormwater management solutions. The National Monuments Foundation and Rodney Cook will fund and construct "sculptures of civil rights leaders, an urban farm, and an 80-foot "peace column."[45][46]

The design mimics Mims Park, now demolished, which was once a prominent city park in Vine City named after Livingston Mims, who was mayor of Atlanta from 1901 to 1903. It was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted's sons, who also designed Piedmont Park in Midtown.[47]

In 2017, it was announced that construction will commence, however the park will be named Rodney Cook Sr. Park and it is hoped to stimulate revitalization.[48] Along with this park, Kathryn Johnston Memorial Park, named in honor of former neighborhood resident Kathryn Johnston, was also built in the neighborhood, being officially opened in 2019.[49]

Other efforts since 2010

In May 2010, the non-profit Greater Vine City Opportunities Program, founded and directed by "Able" Mable Thomas bought the English Avenue Elementary School with the intention to convert it into a "state of the art green technology global community center".[50]

In March 2011, NPU L voted in favor of a Sunset Avenue Historic District from Joseph E. Boone Blvd. southward to Magnolia Street.[5]

In December 2011, the nonprofit Friends of English Avenue arranged for a married couple, both police officers, to live rent-free in a neighborhood house. "Able" Mable Thomas and others expressed the need for a "rebranding" of the area similar to the one which rebranded crime and prostitution-infested Stewart Avenue in Southwest Atlanta as Metropolitan Parkway.[51]

Other transformative efforts continued in 2014. A new Urban Perform gym opened on Joseph E. Boone Blvd designed to empower residents to make healthy lifestyle changes.[52] The gym also hosts a local farmer's market on Saturdays which offers fresh, organic, produce from local community gardens. One of these gardens is the Historic Westside Gardens, which hopes to expand through a cooperative effort with the National Monument Foundation into Mims Park.

The Westside Works, a non-profit and jobs training center, opened in 2014 at the site of former E.R. Carter School at 80 Joseph E. Lowery Blvd. NW. Their mission is to serve the underserved by teaching new skills crucial to the modern workforce. In Summer 2014 they graduated their first class of trainees.[53]

2010s investments

There are multiple efforts underway to encourage and promote home ownership in Vine City and English Avenue. Invest Atlanta has a trust fund which provides up to 10% of the downpayment for a first time homeowner, up to $15,000.[54] Home Atlanta 4.0 provides up to 5% of the house cost, but waives the first-time buyer requirement.

Invest Atlanta and the Arthur M. Blank Foundation partnered to provide $30 million in seed money for innovative and transformative non-profits to help revitalize the two neighborhoods.[citation needed]

In 2018, Friendship Baptist church held talks with developers regarding Downtown West, a new construction development adjacent to the new home of the Atlanta Falcons, Mercedes-Benz Stadium.[55]

Culture

Festivals

In 2012, an annual festival was established, the Historic Westside Village Festival. The event includes educational seminars, vendors, a Kids Zone, and a concert stage, with proceeds going to local charities and services. In 2013 the festival took place on September 21.[56]

The annual English Avenue Festival of Lights is directed by the Historic Westside Cultural Arts Council. The Festival is an exhibition of the community and encourages community members to be a light in their neighborhood. There is a Children's pavilion, free food and drinks, and an exhibition of local non-profits.

Churches

The area is home to a large concentration of churches, including:[57]

- Amazing Grace Church

- Antioch Baptist Church North

- Apostolic Faith Church

- Atlanta Presbyterian Fellowship

- Atlanta Revival Center

- Beulah Baptist Church

- Body of Christ Temple

- Cosmopolitan AME Church

- Faith, Hope and Deliverance Temple

- Faithful Friends Baptist Church

- Grace Midtown Church

- Greater Bethany Baptist Church

- Greater Deliverance Baptist Church

- Greater New Hope Baptist Church

- Greater Springfield Baptist Church

- Greater Vine City Baptist Church

- Heavenly Jerusalem Missionary Baptist Church

- Higher Ground Empowerment Center

- Lilly of the Valley Baptist Church

- Lindsay Street Baptist Church

- Live Life Tabernacle of Praise

- New Jerusalem Baptist Church

- Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church

- Redeemer Community Church

- Simpson Street Church of Christ

- Sims Avenue Baptist Church

- St. James Baptist Church

- St. Mark's Baptist Church

Points of Interest

- Rodney Cook Sr. Park (site, to be developed)

- John F. Kennedy Park

- Kathryn Johnston Memorial Park

- Lindsay Street Park

- Westside Village shopping center

- Herndon Home museum

- King Plow Arts Center

- Morris Brown College

- Architecture of the Sunset Avenue Historic District (proposed)

- Vine City (MARTA station)

- across Northside Drive: Mercedes-Benz Stadium, Georgia World Congress Center

"The Bluff"

The Bluff is a district within the area that is infamous throughout metro Atlanta for the availability of drugs, heroin in particular.[58][59][22] "Bluff" originated as an acronym for "Better Leave, U Fucking Fool".[60]

The borders of The Bluff are defined differently by different sources. For example, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution[22] and Creative Loafing[59] both defined The Bluff as including all of English Avenue and Vine City. However, a more recent and in-depth December 2011 series of reports by 11 Alive TV news, referred to The Bluff as a "section of English Avenue".[8][9][10] The English Avenue/Vine City area has some of the highest poverty and crime rates in the city, with the Carter St. area surrounding the Vine City MARTA station ranking in 2010 as the #1 most dangerous neighborhood in Atlanta and #5 in the United States.[61][62]

Public transportation

The area is served by the MARTA rail Blue Line and Green Line at the Vine City and Ashby stations. Bus lines serving the neighborhood are the 3 along Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, the 51 along Joseph E. Boone Blvd., and the 26 along Cameron M. Alexander Blvd. (known as Kennedy St. until 2010),[63] English Avenue and Donald L. Hollowell Pkwy.[64]

Famous residents

- Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King

- Comedienne Ms. Pat

- State Senator Julian Bond and family resided on Sunset Avenue. The home is still owned and occupied by the family.

- Mary Phagan, victim of notorious 1913 murder at National Pencil Company.

- 2012 Republican presidential candidate Herman Cain spent his early youth here, attending English Avenue School and the age of 10 joining Rev. Cameron M. Alexander's Baptist mega-church.[65]

- Singer Gladys Knight and two of the Pips attended English Avenue Elementary School[66]

- Judge Marvin S. Arrington Sr.[67]

- Mayor Maynard H. Jackson Jr.[67]

- Comedian Bruce Bruce grew up in the Bluff [68]

- Gangster and Star of the 2012 movie Snow on tha Bluff, Curtis Snow

- Rapper Ralo grew up in The Bluff[69]

- Dorothy Bolden, President of the National Domestic Workers Union.

References

- ^ "City of Atlanta, NPU L Map" (PDF). 174.37.215.145. Retrieved April 16, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Thomas Wheatley, "Ambitious parks plans could give Vine City, English Avenue another chance", Creative Loafing, December 8, 2011

- ^ "grants to the Vine City and English Avenue communities" in "Vine City targeted for revitalization", Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 23, 2010

- ^ ""Vine City/English Avenue Trust Fund", Invest Atlanta". Investatlanta.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ a b "The Vine City and English Avenue neighborhoods have voiced their support" in Sunset Avenue Historic District Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b 2010 U.S. census figures as tabulated by WalkScore

- ^ ""Proctor Creek North Avenue Watershed basin", Park Pride" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 20, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ a b "The Bluff: Atlanta's forgotten neighborhood", 11 Alive News (Atlanta)[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b ""Re-branding The Bluff and English Avenue in the ATL', 11 Alive News (Atlanta), December 22, 2011". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ a b ""Return to The Bluff: Not Forgotten any longer", 11 Alive News (Atlanta), December 19, 2011". Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ "Berry and English Fight at the Club". Newspapers.com. The Atlanta Constitution. March 5, 1898. p. 5. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

Judge Berry charges that Mr. English, Jr., drew a pistol and struck him in the face. ...I saw young English's pistol and I am told that he tried to shoot me, but failing to do so, struck me in the face with the weapon.

- ^ "Prisoners Secured From State For $8 Per Month and Hired Out For $14 and $20". Newspapers.com. The Atlanta Journal. October 27, 1902. p. 5. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

James W. English, Jr., sublets 55 convicts to Thomas Jones, at Adrian, Ga.

- ^ a b c "English Avenue Community Redevelopment Plan update" (PDF). Atlantaga.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Years of neglect turn English Avenue home into rotted shell", Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 26, 2002

- ^ a b ""English Avenue Community Campus", Greater Vine City Opportunities Program, Inc". Englishavenuecampus.net. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Citizens ask for better facilities: Crowded condition of Western Heights school cause of complaint", Atlanta Georgian and News, August 19, 1910, p.8

- ^ Clifford M. Kuhn et al., Living Atlanta: An Oral History of the City, 1914–1948

- ^ "Metro Atlanta « Georgia Historic Newspapers". atlnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Crowded schools: more students than ever before threaten to clog all facilities" Life magazine, October 7, 1946, p.40

- ^ a b c ""About Vine City", Vine City Health and Housing Ministry". Vinecity.net. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Furtive Dynamiters Blast Big Atlanta Negro School", Meriden Record, December 13, 1960

- ^ a b c d Andria Simmons, "Heroin a deadly draw in 'Bluff'", Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 7, 2011

- ^ Blau, Max; Michney, Todd (December 12, 2020). "Terror in the City Too Busy to Hate: How the English Avenue School Bombing Challenged Atlanta's Popular Myth of Racial Progress". Atlanta Studies. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ "Forming Mobs Turn into Anti-Black Power Rally", Lodi News-Sentinel, September 6, 1966

- ^ "Negro Disorders Erupt in Atlanta Slum Section", Rome News-Tribune, October 24, 1967

- ^ Patrik Jonsson, "After Atlanta raid tragedy, new scrutiny of police tactics", Christian Science Monitor, November 29, 2006

- ^ "11alive.com". WXIA. Retrieved April 16, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Search - Atlanta Creative Loafing". Atlanta Creative Loafing. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "The Stadium Effect", Thomas Wheatley, Creative Loafing, September 6, 2012

- ^ "Empowerment zones: Boondoggle or aid to poor?", Atlanta Business Chronicle, November 6, 2000

- ^ Scott Henry, "Federal grants go to groups with shaky past", Creative Loafing, September 26, 2007

- ^ Joeff Davis, "Photo of the Day: Herndon Homes demolition", Creative Loafing, February 2010]

- ^ "Westside due a $130 million redo", Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 16, 1999

- ^ "A DREAM FULFILLED: Intown Publix to open", Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 30, 2002

- ^ David Pendered, "Entangled in Vine City; 'The city lost control': Officials scramble to save project to renew Historic Westside Village" Archived 2012-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 28, 2003

- ^ "Historic Westside Village Publix To Close, Residents Not Happy". Majicatl.com. December 9, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Scott Henry, "Westside Do-over", Creative Loafing, April 26, 2006

- ^ "Home". Atlantada.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Home" (PDF). Atlantada.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ EndPlay (January 23, 2013). "New Walmart opens in Vine City". Wsbtv.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Vine City/AUC Walmart Grand Opening on Wednesday 1/23: Walmart has said they are ready to open to the public", Marc Richardson, Cascade Patch, January 21, 2013

- ^ "New Life for Atlanta's English Avenue", Patrik Jonsson,Christian Science Monitor, December 11, 2008

- ^ "Park Design". Cooks Park. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ "Remember Historic Mims Park? It Could Start Happening Soon". Atlanta.curbed.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ McWilliams, Jeremiah (July 16, 2012). "Atlanta council approves Mims park proposal". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ National Monuments Foundation (October 22, 2012). "Historic Mims Park". YouTube. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Wheatley, Thomas (December 8, 2011). "Ambitious parks plans could give Vine City, English Avenue another chance". Creative Loafing. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ "Westside park could have potential of Historic Fourth Ward Park". Myajc.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Green, Josh (November 22, 2019). "Atlanta park opens in honor of 92-year-old neighborhood matriarch killed by police". Curbed Atlanta. Vox Media. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ ""About GVCOP", Greater Vine City Opportunities Program, Inc". Englishavenuecampus.net. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ ""Re-branding the Bluff and English Ave. in the ATL", WXIA-TV (11 Alive), December 22, 2011". 11alive.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Staples, Gracie Bonds (June 18, 2014). "A safe place to exercise". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ^ "Our Programs « Westside Works". Westsideworks.org. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Vine City / English Avenue Trust Fund (HOAP) | Invest Atlanta". Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ^ "Downtown West Envisioned Around New Falcons". Bizjournals.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Historic Westside Village Festival website". Hwvfestival.org. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Divine mission gives way to blighted streets". Myajc.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Atlanta Magazine, "The King File", 4/15/2009 Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Search - Atlanta Creative Loafing". Atlanta Creative Loafing. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Butler, Blake (June 1, 2012). "Snow on tha Bluff". Vice. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Alexis stevens, "Study: 4 Atlanta neighborhoods among nation's most dangerous", Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 5, 2010

- ^ "My Portfolios - Finance Portfolio". Dailyfinance.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ City of Atlanta online, ordinace 10-O-1420 Archived 2011-11-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "MARTA". Itsmarta.com. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "The Herman Cain of Atlanta's West Side". Cascade.patch.com. October 16, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Harmon Perry, "Gladys Knight and the Pips: Too hot to stop", Jet magazine, June 20, 1974

- ^ a b "Sidewalk Stories". Peopletv.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Scott Gargan, "Connecticut Comedy Festival at Bridgeport arena", The News-Times (Danbury, Conn.), October 11, 2011

- ^ "Rapper Ralo Talks The Bluff, Atlanta's Drug-Infested Neighborhood". Vibe.com. March 5, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

External links

- Newberry, Brittany. "Black Neighborhoods and the Creation of Black Atlanta". Digital Exhibits. Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

- Photographs of "the forgotten Bluff"