1923–24 Egyptian parliamentary election

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

|

|---|

|

|

| Constitution (history) |

| Political parties (former) |

|

|

Parliamentary elections were held in two stages in Egypt in 1923 and 1924, the first since nominal independence from the United Kingdom in 1922. The result was a victory for the Wafd Party, which won 188 of the 215 seats.[1]

Background

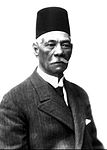

The British government unilaterally recognized Egypt's independence on 28 February 1922. The Kingdom of Egypt was established two weeks later. On 21 April 1923, a new liberal constitution was promulgated. A royal decree was published on 6 September of the same year, which ordered the holding of the first election under the new constitution. Nationalist leader Saad Zaghloul, who had been exiled to Aden, Seychelles and Gibraltar, returned to Egypt on 17 September to take part in the electoral campaign.[2] Zaghloul and his partisans ran a campaign that exposed the problems of the newly established constitutional order. Zaghloul was especially critical of the electoral laws, which he viewed as incompatible with democracy since they made eligibility of candidacy to general elections conditional on income. The Students Executive Committee of Zaghloul's Wafd Party played a crucial role in the campaign.[3]

System

The election was held over two stages. In the first stage on 27 September 1923, 38,000 electoral representatives were elected by the general population.[4] These were announced on 3 October.[4] In the second stage on 12 January 1924 the representatives elected members of the new Parliament.[4]

Results

Zaghloul's Wafd Party, which had run for all Chamber of Deputies seats, won a landslide victory, winning 188 of the 215 seats.[1] However, it fared less well in the Senate because it was harder to find qualified candidates to run for its constituencies.[5] It won 66 Senate seats.[6] Wafdist voters included the medium and small landowners, urban professionals, merchants and industrialists, shopkeepers, workers and peasants.[5]

Members of Egypt's Coptic Christian minority received 10% of the seats.[7] This was higher than the Copts' share of Egypt's population, which stood at six percent according to the 1917 census. The social origin of the Copts who had been elected was very similar to that of the Muslims: mostly wealthy landowners, but also a small number of middle-class professionals, mostly lawyers as well as a few doctors. Two-thirds of the districts that elected Copts were in Upper Egypt, and one-third in Lower Egypt. The Wafd was the only party that managed to get Coptic candidates elected in the Nile Delta region of Lower Egypt, where Copts were not very numerous. It felt vindicated by these results, which were a clear sign of the party's strength and a testament to its commitment to secularism and national unity.[8]

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Party | Seats | |

| Wafd Party | 188 | |

| Other parties and independents | 27 | |

| Total | 215 | |

| Source: Sternberger et al. | ||

Aftermath

The Wafd Party's resounding victory meant that King Fuad I had no choice but to ask Zaghloul to form a new government. He did so on 27 January, and Zaghloul was named Prime Minister of Egypt.[9] The Wafd felt it had a mandate to conclude a treaty with the United Kingdom that would assure Egypt complete independence.[10] As prime minister, Zaghloul carefully selected a cross-section of Egyptian society for his cabinet, which he called the "People's Ministry".[10] On 15 March 1924, King Fuad opened the first Egyptian constitutional parliament amid national rejoicing.[10] The Wafdist government did not last long, however.[10]

On 19 November 1924, Sir Lee Stack, the British governor general of Sudan and commander of the Egyptian Army, was assassinated in Cairo.[10] The assassination was one of a series of killings of British officials that had begun in 1920.[10] Viscount Allenby, the British High Commissioner to Egypt, considered Stack an old and trusted friend.[10] He was thus determined to avenge the crime and in the process humiliate the Wafd and destroy its credibility in Egypt.[10] Allenby demanded that Egypt apologize, prosecute the assailants, pay a £500,000 indemnity, withdraw all troops from Sudan, consent to an unlimited increase of irrigation in Sudan and end all opposition to the capitulations (Britain's demand of the right to protect foreign interests in the country).[10] Zaghloul wanted to resign rather than accept the ultimatum, but Allenby presented it to him before Zaghloul could offer his resignation to the king.[10] Zaghloul and his cabinet decided to accept the first four terms but to reject the last two.[10] On 24 November, after ordering the Ministry of Finance to pay the indemnity, Zaghloul resigned.[10] He died three years later.[10]

See also

References

- ^ a b Dolf Sternberger, Bernhard Vogel, Dieter Nohlen & Klaus Landfried (1978) Die Wahl der Parlamente: Band II: Afrika, Erster Halbband, p294 (in German)

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (1927). The Islamic World Since the Peace Settlement (snippet view). Survey of International Affairs, Vol. 1. London: Oxford University Press. p. 205. OCLC 21169232. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ Maghraoui, Abdeslam (2006). Liberalism Without Democracy: Nationhood and Citizenship in Egypt, 1922–1936. Politics, History, and Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8223-3838-3. OCLC 469693850. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ a b c Democracy is born Archived 2011-12-16 at the Wayback Machine Al-Ahram Weekly, 25–31 May 2000, No. 483

- ^ a b Goldschmidt, Arthur; Johnston, Robert (2004). Historical Dictionary of Egypt (3rd ed.). American University in Cairo Press. p. 412. ISBN 978-977-424-875-7. OCLC 58833952.

- ^ "Nationalists Win in Egypt" (fee required). The New York Times. 1924-02-25. p. 7. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ Schrand, Irmgard (2004). Jews in Egypt: Communists and Citizens (snippet view). Studien zur Zeitgeschichte des Nahen Ostens und Nordafrikas, Vol. 10. Münster: Lit. p. 36. ISBN 978-3-8258-7516-9. OCLC 56657957. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ Hassan, Sana (2003). Christians versus Muslims in Modern Egypt: The Century-Long Struggle for Coptic Equality. New York: Oxford University Press US. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-19-513868-9. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ Sicker, Martin (2001). The Middle East in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-275-96893-9. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. (1991). Egypt: a country study (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 50. ISBN 0-8444-0729-1. OCLC 24247439.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)