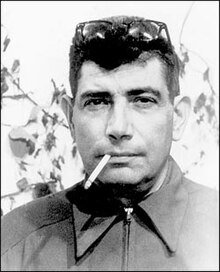

Edgar G. Ulmer

Edgar G. Ulmer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 17, 1904 |

| Died | September 30, 1972 (aged 68) |

| Occupation(s) | Film director, screenwriter, set designer |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse | Shirley Ulmer (married 1935 -) |

| Children | Arianne Ulmer |

Edgar Georg Ulmer (/ˈʌlmər/; September 17, 1904 – September 30, 1972) was an Austrian film director who worked mainly in Hollywood B movies and other low-budget productions, eventually earning the epithet 'The King of PRC',[1] due to his extremely prolific output for the Poverty Row studios. His stylish and eccentric works came to be appreciated by auteur theory-espousing film critics in the years following his retirement. Ulmer's most famous productions include the horror film The Black Cat (1934) and the film noir Detour[2] (1945).

Biography

Ulmer was born in Olomouc, Austria-Hungary, in what is now the Czech Republic. His family were Moravian Jews.[3] As a young man he lived in Vienna, where he worked as a stage actor and set designer while studying architecture and philosophy.[4] He did set design for Max Reinhardt's theater, served his apprenticeship with F. W. Murnau, and worked with directors including Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fred Zinnemann and cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, inventor of the Schüfftan process. He also claimed to have worked on Der Golem (1920), Metropolis (1927), and M (1931), but there is no evidence to support this. Ulmer came to Hollywood with Murnau in 1926 to assist with the art direction on Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927). In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, he also recalled making two-reel westerns in Hollywood around this time.[5]

Film director

The first feature he directed in North America, Damaged Lives (1933), was a low-budget exploitation film exposing the horrors of venereal disease. His next film, The Black Cat (1934), starring Béla Lugosi and Boris Karloff, was made for Universal Pictures. Demonstrating the striking visual style that would be Ulmer's hallmark, the film was Universal's biggest hit of the season.[6] Ulmer, however, had begun an affair with Shirley Beatrice Kassler, who had been married since 1933 to independent producer Max Alexander, nephew of Universal studio head Carl Laemmle. Kassler's divorce in 1936 and her marriage to Ulmer later the same year led to his being exiled from the major Hollywood studios. Ulmer was relegated to making B movies at Poverty Row production houses.[7] His wife, now Shirley Ulmer, acted as script supervisor on nearly all of these films, and she wrote the screenplays for several. Their daughter, Arianne, appeared as an extra in several of his films.

Consigned to the fringes of the U.S. motion picture industry, for a time Ulmer specialized first in "ethnic films," in Ukrainian—Natalka Poltavka (1937), Cossacks in Exile (1939)—and Yiddish—The Light Ahead (1939), Americaner Shadchen (1940).[8] The best-known of these ethnic films is the Yiddish Green Fields (1937), co-directed with Jacob Ben-Ami.

Ulmer eventually found a niche making melodramas on tiny budgets and with often unpromising scripts and actors for Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC), with Ulmer describing himself as "the Frank Capra of PRC".[9][10] His PRC thriller Detour (1945) has won considerable acclaim as a prime example of low-budget film noir, and it was selected by the Library of Congress among the first group of 100 American films worthy of special preservation efforts. In 1947, Ulmer made Carnegie Hall with the help of conductor Fritz Reiner, godfather of the Ulmers' daughter, Arianné. The film features performances by many leading figures in classical music, including Reiner, Jascha Heifetz, Artur Rubinstein, Gregor Piatigorsky and Lily Pons.[11] Ulmer did get a chance to direct two films with substantial budgets, The Strange Woman (1946) and Ruthless (1948). The former, featuring a strong performance by Hedy Lamarr, is regarded by critics as one of Ulmer's best. He directed a low-budget science-fiction film with a noirish tone, The Man from Planet X (1951). His last film, The Cavern (1964), was shot in Italy.

Death

Ulmer died in 1972 in Woodland Hills, California, after a crippling stroke. He is interred in the Hall of David Mausoleum in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Hollywood, CA. His wife, Shirley Ulmer, is interred nearby.

Legacy

Commemorating the 30th anniversary of his death, a three-day symposium of lectures and screenings was held at New York City's New School in November 2002. In 2005, researcher Bernd Herzogenrath uncovered the address where Ulmer was born in Olomouc. A memorial plaque commemorating Ulmer's birth home was unveiled on September 17, 2006, on the occasion of Ulmerfest 2006—the first European academic conference devoted to Ulmer's work.

The moving image collection of Edgar G. Ulmer is held at the Academy Film Archive. The film material at the Academy Film Archive is complemented by material in the Edgar G. Ulmer papers at the Academy's Margaret Herrick Library.[12]

Partial filmography

as set designer (disputed):

- Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (1920)

- Sodom und Gomorrha (1922)

- Metropolis (1927)

- M (1931)

as co-director:

- People on Sunday (1930)

as director:

- Damaged Lives (1933)

- The Black Cat (1934)

- Thunder Over Texas (1934)

- From Nine to Nine (1936)

- Natalka Poltavka (1937)

- Green Fields [Grine Felder] (1937) (co-directed with Jacob Ben-Ami)

- The Singing Blacksmith [Yankl der Schmid / Yankl the Blacksmith] (1938)

- Fishka der Krimmer [Fishka the Cripple] (1939)

- The Light Ahead (1939)

- Cossacks in Exile (1939)

- Moon Over Harlem (1939)

- Let My People Live (1939) – 13-minute short for the National Tuberculosis Association

- Cloud in the Sky (1940) – 19-minute short for the National Tuberculosis Association

- Goodbye, Mr. Germ (1940) – 14-minute partially animated short for the National Tuberculosis Association

- They Do Come Back (1940) – 16-minute short for the National Tuberculosis Association

- Americaner Schadchen [American Matchmaker] (1940)

- Tomorrow We Live (1942)

- My Son, the Hero (1943)

- Girls in Chains (1943)

- Isle of Forgotten Sins (1943)

- Jive Junction (1943)

- Bluebeard (1944)

- Strange Illusion (1945)

- Detour (1945)

- Club Havana (1945)

- The Strange Woman (1946)

- The Wife of Monte Cristo (1946)

- Her Sister's Secret (1946)

- Carnegie Hall (1947)

- Ruthless (1948)

- The Pirates of Capri (1949)

- The Man from Planet X (1951)

- St. Benny the Dip (1951)

- Babes in Bagdad (1952)

- Murder Is My Beat (1955)

- The Naked Dawn (1955)

- The Daughter of Dr. Jekyll (1957)

- Swiss Family Robinson: Lost in the Jungle (1958)

- The Naked Venus (1958)

- Hannibal (1959)

- The Amazing Transparent Man (1960)

- Beyond the Time Barrier (1960)

- Journey Beneath the Desert (1961)

- The Cavern (1964)

Personal quotes

- "I really am looking for absolution for all the things I had to do for money's sake."[13]

References

- ^ "Edgar G. Ulmer". IMDb. Archived from the original on 2016-09-21.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1998-06-07). "Great Movies: Detour". rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-12. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Year of Jewish Culture – 100 Years of the Jewish Museum in Prague Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Edgar G. Ulmer | American director". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-06-15.

- ^ Bogdanovich, Peter (1997) Who the Devil made it : conversations with Robert Aldrich, George Cukor, Allan Dwan, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Chuck Jones, Fritz Lang, Joseph H. Lewis, Sidney Lumet, Leo McCarey, Otto Preminger, Don Siegel, Josef von Sternberg, Frank Tashlin, Edgar G. Ulmer, Raoul Walsh in libraries (WorldCat catalog) (New York: Knopf) ISBN 978-0-3454-0457-2

- ^ Mank, Gregory William (1990). Karloff and Lugosi: The Story of a Haunting Collaboration (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland), p. 81.

- ^ Cantor, Paul A. (2006). "Film Noir and the Frankfurt School: America as Wasteland in Edgar G. Ulmer's Detour," in The Philosophy of Film Noir, ed. Mark T. Conard (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky), p. 143. ISBN 0-8131-2377-1.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (2004). Never Coming To A Theater Near You: A Celebration of a Certain Kind of Movie (New York: PublicAffairs), p. 364. ISBN 1-58648-231-9.

- ^ p. 62 Robson, Eddie Edgar G. Ulmer Interview in Film Noir Virgin, 2005

- ^ p.241 Norman, Barry The Story of Hollywood New American Library, 1988

- ^ Cantor (2006), p. 150.

- ^ "Edgar G. Ulmer Collection". Academy Film Archive.

- ^ Bogdanovich (1997), p. 603.

Bibliography

- Bernd Herzogenrath: Edgar G. Ulmer. Essays on the King of the B's. Jefferson, NC 2009, ISBN 978-0-7864-3700-9

- Bernd Herzogenrath: The Films of Edgar G. Ulmer. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. (2009) ISBN 978-0-8108-6700-0

- Noah Isenberg: Detour. London: BFI Film Classics, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84457-239-7

- Noah Isenberg: Edgar G. Ulmer: A Filmmaker at the Margins. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-5202-3577-9

- Tony Tracy: "The Gateway to America": Assimilation and Art in Carnegie Hall (1947)" in Gary D. Rhodes, Edgar G. Ulmer: Detour on Poverty Row. Lexington Books, 2008. ISBN 0-7391-2568-0

External links

- Edgar G. Ulmer Bibliography (via UC Berkeley)

- "Magic on a shoestring": Geoffrey Macnab on why movie directors could all learn a lesson from Edgar G Ulmer

- Senses of Cinema: Great Directors Critical Database

- Edgar G. Ulmer at IMDb

- Info on Ulmer and program of Ulmerfest 2006

- The American Cinematheque presents...Strange Illusions: The Films of Edgar G. Ulmer Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Literature on Edgar G. Ulmer