History of East Asia

The history of East Asia generally encompasses the histories of China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, and Taiwan from prehistoric times to the present.[1] Each of its countries has a different national history, but East Asian Studies scholars maintain that the region is also characterized by a distinct pattern of historical development.[2] This is evident in the relationships among traditional East Asian civilizations, which not only involve the sum total of historical patterns but also a specific set of patterns that has affected all or most of traditional East Asia in successive layers.

Background

Field of study and scope

The study of East Asian history is a part of the rise of East Asian studies as an academic field in the Western world. The teaching and studying of East Asian history began in the West during the late 19th century.[3] In the United States, Asian Americans around the time of the Vietnam War believed that most history courses were Eurocentric and advocated for an Asian-based curriculum. At the present time, East Asian History remains a major field within Asian Studies. Nationalist historians in the region tend to stress the uniqueness of their respective country's tradition, culture, and history because it helps them legitimize their claim over territories and minimize internal disputes.[4] There is also the case of individual authors influenced by different concepts of society and development, which lead to conflicting accounts.[4] These, among other factors, led some scholars to stress the need for broader regional and historical frameworks.[2] There have been issues with defining exact parameters for what East Asian history which as an academic study has focused on East Asia's interactions with other regions of the world.[5] Scholars such as Andrew Abalahin have argued that East Asia and its neighboring region of Southeast Asia form a single ethno-cultural area, sharing common roots and history with each other, while being distinct from other world regions.[6] Historian Charles Holcombe states that East Asia as a unified cultural region can be defined by adherence to Confucianism, influences from Buddhism and a usage of chopsticks.[1] Nomadic Peoples to China's north including Turkic, Manchu and Mongolian tribes were sinicized over time, this assimilation often occurred as a result of nomadic conquest of China rather than Chinese conquest of the steppe.[7]

Summary of history

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

Recorded civilization dates to approximately 2000 BC in China's Shang dynasty along the Yellow River Valley, though the historically disputed Zhou Dynasty is said to have existed even earlier. Civilization expanded to other areas in East Asia gradually. In Korea Gojoseon became the first organized state around approximately 195 BC. Japan emerged as a unitary state with the creation of its first constitution in 604 AD. The introduction of Buddhism and the Silk Road were instrumental in building East Asia's culture and economy.

Chinese dynasties such as the Sui, Tang and Song interacted with and influenced the characters of early Japan and Korea. At the turn of the first millennium AD, China was the most advanced civilization in East Asia and was responsible for the Four Great Inventions. China's GDP was likely the largest in the world at times as well.

The rise of the nomadic Mongol Empire disrupted East Asia, and under the leadership of leaders such as Genghis Khan, Subutai, and Kublai Khan brought the majority of East Asia under rule of a single state, with the exception of Japan and Taiwan. The Yuan dynasty. The Yuan dynasty attempted and failed to conquer Japan in two separate maritime invasions. The Mongol era in East Asia was short-lived due to natural disasters and poor administrative management. In the aftermath of the Yuan dynasty's collapse, new regimes such as the Ming dynasty and Joseon dynasty embraced Neo-Confucianism as the official state ideology. Japan at this time fell into feudal civil war known as the Sengoku Jidai which persisted for over a century and a half. At the turn of the 16th century European merchants and missionaries traveled to East Asia by sea for the first time. The Portuguese established a colony in Macau, China and attempted to Christianize Japan. In the last years of the Sengoku period, Japan attempted to create a larger empire by invading Korea only being defeated by the combined forces of Korea and China in the late 16th century.

From the 17th century onward, East Asian nations such as China, Japan, and Korea chose a policy of isolationism in response to European contact. The 17th and 18th centuries saw great economic and cultural growth. Qing China dominated the region but Edo Japan remained completely independent. At this time limited interactions with European merchants and intellectuals led to the rise of Great Britain's East India Company and the beginning of Japan's Dutch studies. However, 1800s saw the rise of European imperialism in the region. Qing China was unable to defend itself from various colonial expeditions from Great Britain, France, and Russia during the Opium Wars. Japan meanwhile choose the path of westernization under the Meiji period and attempted to modernize by following the political and economic models of Europe and the Western World. The rising Japanese Empire forcibly annexed Korea in 1910. After years of civil war and decline, China's last emperor Puyi abdicated in 1912 ending China's imperial history which had persisted for over two millennium from the Qin to Qing.

In the midst of the Republic of China's attempts to build a modern state, Japanese expansionism pressed onward in the first half of the twentieth century, culminating in the brutal Second Sino-Japanese War where over twenty million people died during Japan's invasion of China. Japan's wars in Asia became a part of WWII after Japan's attack of the United States' Pearl Harbor. Japan's defeat in Asia by the hand of the allies contributed to the creation of a new world order under American and Soviet influence across the world. Afterwards, East Asia was caught in the cross hairs of the Cold War. The People's Republic of China initially fell under the sphere of the Soviet camp but Japan under American occupation was solidly tied to Western nations. Japan's recovery became known as the post-war economic miracle. Soviet and Western competition led to the Korean War, which created two separate states that exist in present times.

The end of the Cold War and the rise of globalization have brought South Korea, and the People's Republic of China into the world economy. Since 1980, the economies and living standards of South Korea and China have increased exponentially. In contemporary times, East Asia is a pivotal world region with a major influence on world events. In 2010, East Asia's population made up approximately 24% of the world's population.[8]

Prehistory

Homo erectus ("upright man") is believed to have lived in East Asia from 1.8 million to 40,000 years ago.

In China specifically, fossils representing 40 Homo erectus individuals, known as Peking Man, were found near Beijing at Zhoukoudian that date to about 400,000 years ago. The species was believed to have lived for at least several hundred thousand years in China,[9] and possibly until 200,000 years ago in Indonesia[citation needed]. They may have been the first to use fire and cook food.[10] Homo sapiens migrated into inland Asia, likely by following herds of bison and mammoth and arrived in southern Siberia by about 43,000 years ago and some people moved south or east from there.[11][12] The earliest sites of neolithic culture include Nanzhuangtou culture around 9500 BC to 9000 BC,[13] Pengtoushan culture around 7500 BC to 6100 BC, Peiligang culture around 7000 BC to 5000 BC. China's first villages appeared on the landscape at this time.

In Korea the Jeulmun pottery period is sometimes labeled the "Korean Neolithic", but since intensive agriculture and evidence of European-style 'Neolithic' lifestyle is sparse at best, such terminology is misleading.[14] The Jeulmun was a period of hunting, gathering, and small-scale cultivation of plants from 20,000 BC to 8000 BC.[14][15] Archaeologists sometimes refer to this life-style pattern as 'broad-spectrum hunting-and-gathering'.

The Jōmon period occurred in Japan from circa 14,000 BC to 300BC, with some characteristics of both Neolithic and Mesolithic culture.

Ancient East Asia (4,000 BC- 1,000 AD)

Ancient Chinese dynasties

The Xia dynasty of China (from c. 2100 to c. 1600 BC) is the first dynasty to be described in ancient historical records such as Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian and Bamboo Annals.[16][17]

Following this was the Shang dynasty, which ruled in the Yellow River valley. The classic account of the Shang comes from texts such as the Book of Documents, Bamboo Annals and Records of the Grand Historian. According to the traditional chronology, the Shang ruled from 1766 BC to 1122 BC, but according to the chronology based upon the "current text" of Bamboo Annals, they ruled from 1556 BC to 1046 BC.

The Zhou dynasty of c. 1046–256 BC lasted longer than any other dynasty in Chinese history. However, the actual political and military control of China by the dynasty, surnamed Ji (Chinese: 姬), lasted only until 771 BC, a period known as the Western Zhou. This period of Chinese history produced what many consider the zenith of Chinese bronze-ware making. The dynasty also spans the period in which the written script evolved into its modern form with the use of an archaic clerical script that emerged during the late Warring States period.

Nomads on the Mongolian Steppe

The territories of modern-day Mongolia and Inner Mongolia in ancient times was inhabited by nomadic tribes. The cultures and languages in these areas were fluid and changed frequently. The use of horses to herd and move started during the Iron Age. A large area of Mongolia was under the influence of Turkic peoples, while the southwestern part of Mongolia was mostly under the influence of Indo-European peoples such as the Tocharians and Scythian tribes. In antiquity, the eastern portions of both Mongolia and Inner Mongolia were inhabited by Mongolic peoples descended from the Donghu people and numerous other tribes These were Tengriist horse-riding pastoralist kingdoms that had close contact with the agrarian Chinese. As a nomadic confederation composed of various clans the Donghu were prosperous in the 4th century BC, forcing surrounding tribes to pay tribute and constantly harassing the Chinese State of Zhao (325 BC, during the early years of the reign of Wuling). To appease the nomads local Chinese rulers often gave important hostages and arranged marriages. In 208 BC Xiongnu emperor Modu Chanyu, in his first major military campaign, defeated the Donghu, who split into the new tribes Xianbei and Wuhuan. The Xiongnu were the largest nomadic enemies of the Han dynasty fighting wars for over three centuries with the Han dynasty before dissolving. Afterwards the Xianbei returned to rule the Steppe north of the Great Wall. The titles of Khangan and Khan originated from the Xianbei.

Ancient Korea

According to the Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms, Gojoseon was established in 2333 BC by Dangun, who was said to be the offspring of a heavenly prince and a bear-woman. Gojoseon fostered an independent culture in Liaoning and along the Taedong River. In 108 BC, the Chinese Han dynasty under Emperor Wu invaded and conquered Gojoseon. The Han established four commanderies to administer the former Gojoseon territory. After the fragmentation of the Han Empire during the 3rd century and the subsequent chaotic 4th century, the area was lost from the Chinese was reconquered by the Empire of Goguryeo in 313 AD.

In 58 BC, the Korean Peninsula was divided into three kingdoms, Baekje, Silla and Goguryeo. Although they shared a similar language and culture, these three kingdoms constantly fought with each other for control of the peninsula. Furthermore, Goguryeo had been engaged in constant wars with the Chinese. This included the Goguryeo–Sui War, where the Kingdom of Goguryeo managed to repel the invading forces of the Sui dynasty.

As the Kingdom of Silla conquered nearby city-states, they gained access to the Yellow Sea, making direct contact with the Tang dynasty possible. The Tang dynasty teamed up with Silla and formed a strategy to invade Goguryeo. Since Goguryeo had been able to repel earlier Chinese invasions from the North, perhaps Gorguryeo would fall if it were attacked by Silla from the south at the same time. However, in order to do this, the Tang-Silla alliance had to eliminate Goguryeo's nominal ally Baekje and secure a base of operations in southern Korea for a second front. In 660, the coalition troops of Silla and Tang of China attacked Baekje, resulting in the annexation of Baekje by Silla. Together, Silla and Tang effectively eliminated Baekje when they captured the capital of Sabi, as well as Baekje's last king, Uija, and most of the royal family. However, Yamato Japan and Baekje had been long-standing and very close allies. In 663, Baekje revival forces and a Japanese naval fleet convened in southern Baekje to confront the Silla forces in the Battle of Baekgang. The Tang dynasty also sent 7,000 soldiers and 170 ships. After five naval confrontations that took place in August 663 at Baekgang, considered the lower reaches of Tongjin river, the Silla–Tang forces emerged victorious.

The Silla–Tang forces turned their attention to Goguryeo. Although Goguryeo had repelled the Sui dynasty a century earlier, attacks by the Tang dynasty from the west proved too formidable. The Silla–Tang alliance emerged victorious in the Goguryeo–Tang War. Silla thus unified most of the Korean Peninsula in 668. The kingdom's reliance on China's Tang dynasty had its price. Silla had to forcibly resist the imposition of Chinese rule over the entire peninsula. Silla then fought for nearly a decade to expel Chinese forces to finally establish a unified kingdom as far north as modern Pyongyang.

Early Japan

Japan was inhabited more than 30,000 years ago, when land bridges connected Japan to Korea and China to the south and Siberia to the north. With rising sea levels, the 4 major islands took form around 20,000 years ago, and the lands connecting today's Japan to the continental Asia completely disappeared 15,000 to 10,000 years ago. Thereafter, some migrations continued by way of the Korean peninsula, which would serve as Japan's main avenue for cultural exchange with the continental Asia until the medieval period. The mythology of ancient Japan is contained within the Kojiki ('Records of Ancient Matters') which describes the creation myth of Japan and its lineage of Emperors to the Sun Goddess Amaterasu.

Ancient pottery has been uncovered in Japan, particularly in Kyushu, that points to two major periods: the Jōmon (c. 7,500–250 BC, 縄文時代 Jōmon Jidai ) and the Yayoi (c. 250 BC – 250 AD, 弥生時代 Yayoi Jidai). Jōmon can be translated as 'cord marks' and refers to the pattern on the pottery of the time; this style was more ornate than the later Yayoi type, which has been found at more widespread sites (e.g. around Tokyo) and seems to have been developed for more practical purposes.

Birth of Confucianism and Taoism

Confucianism and Taoism originated in the Spring and Autumn period, arising from the historic figures of Confucius and Laozi. They have functioned has both competing and complementary belief systems. Confucianism emphasizes social order and filial piety while Taoism emphasizes the universal force of the Tao and spiritual well-being.

Confucianism is an ethical and philosophical system that developed during the Spring and Autumn period. It later developed metaphysical and cosmological elements in the Han dynasty.[18] Following the official abandonment of Legalism in China after the Qin dynasty, Confucianism became the official state ideology of the Han. Nonetheless, from the Han period onwards, most Chinese emperors have used a mix of Legalism and Confucianism as their ruling doctrine. The disintegration of the Han in the second century CE opened the way for the soteriological doctrines of Buddhism and Taoism to dominate intellectual life at that time.

A Confucian revival began during the Tang dynasty. In the late Tang, Confucianism developed aspects on the model of Buddhism and Taoism that gradually evolved into what is now known as Neo-Confucianism. This reinvigorated form was adopted as the basis of the imperial exams and the core philosophy of the scholar-official class in the Song dynasty. Confucianism would reign supreme as an ideology influencing all of East Asia until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911.

Taoism as a movement originates from the semi mystical figure of Laozi, who allegedly lived during the 6th–5th century BC. His teachings revolved around personal serenity, balance in the universe and the life source of the Tao. The first organized form of Taoism, the Tianshi (Celestial Masters') school (later known as Zhengyi school), developed from the Five Pecks of Rice movement at the end of the 2nd century CE; the latter had been founded by Zhang Daoling, who claimed that Laozi appeared to him in the year 142.[19] The Tianshi school was officially recognized by ruler Cao Cao in 215, legitimizing Cao Cao's rise to power in return.[20] Laozi received imperial recognition as a divinity in the mid-2nd century BCE.[21]

Taoism, in form of the Shangqing School, gained official status in China again during the Tang dynasty (618–907), whose emperors claimed Laozi as their relative.[22] The Shangqing movement, however, had developed much earlier, in the 4th century, on the basis of a series of revelations by gods and spirits to a certain Yang Xi in the years between 364 and 370.[23]

Qin and Han dynasties

In 221 BC, the state of Qin succeeded in conquering the other six states, creating the first imperial dynasty of China for the first time. Following the death of the emperor Qin Shi Huang, the Qin dynasty collapsed and control was taken over by the Han dynasty in 206 BC. In 220 AD, the Han empire collapsed into the Three Kingdoms. The series of trade routes known as Silk Road began during the Han dynasty.

Qin Shi Huang ruled the unified China directly with absolute power. In contrast to the decentralized and feudal rule of earlier dynasties the Qin set up a number of 'commanderries' around the country which answered directly to the emperor. Nationwide the political philosophy of Legalism was used as a means of the statecraft and writings promoting rival ideas such as Confucianism were prohibited or controlled. In his reign China created the first continuous Great Wall with the use of forced labor and Invasions were launched southward to annex Northern Vietnam. Eventually, rebels rose against the Qin's brutal reign and fought civil wars for control of China. Ultimately the Han dynasty arose and ruled China for over four centuries in what accounted for a long period in prosperity, with a brief interruption by the Xin dynasty. The Han dynasty fought constant wars with nomadic Xiongnu for centuries before finally dissolving the tribe.

The Han dynasty played a great role in developing the Silk Road which would transfer wealth and ideas across Eurasia for millennia, and also invented paper. Though the Han enjoyed great military and economic success it was strained by the rise of aristocrats who disobeyed the central government. Public frustration provoked the Yellow Turban Rebellion – though a failure it nonetheless accelerated the empire's downfall. After 208 AD the Han dynasty broke up into rival kingdoms. China would remain divided until 581 under the Sui dynasty, during the era of division Buddhism would be introduced to China for the first time.

Era of disunion in China

The Three Kingdoms period consisted of the kingdom of Wei, Shu, and Wu. It began when the ruler of Wei, Cao Cao, was defeated by Liu Bei and Sun Quan at the Battle of Red Cliffs. After Cao Cao's death in AD 220, his son Cao Pi became emperor of Wei. Liu Bei and Sun Quan declared themselves emperor of Shu and Wu respectively. Many famous personages in Chinese history were born during this period, including Hua Tuo and the great military strategist Zhuge Liang. Buddhism, which was introduced during the Han dynasty, also became popular in this period. Two years after Wei conquered Shu in AD 263, Sima Yan, Wei's Imperial Chancellor, overthrew Wei and started the Western Jin dynasty. The conquest of Wu by the Western Jin dynasty ended the Three Kingdoms period, and China was unified again. However, the Western Jin did not last long. Following the death of Sima Yan, the War of the Eight Princes began. This war weakened the Jin dynasty, and it soon fell to the kingdom of Han-Zhao. This ushered in the Sixteen Kingdoms.

The Northern Wei was established by the Tuoba clan of the Xianbei people in AD 386, when they united the northern part of China. During the Northern Wei, Buddhism flourished, and became an important tool for the emperors of the Northern Wei, since they were believed to be living incarnations of Buddha. Soon, the Northern Wei was divided into the Eastern Wei and Western Wei. These were followed by the Northern Zhou and Northern Qi. In the south, the dynasties were much less stable than the Northern dynasties. The four Southern dynasties were weakened by conflicts between the ruling families.

Spread of Buddhism

Buddhism, also one of the major religions in East Asia, was introduced into China during the Han dynasty from Nepal in the 1st century BC. Buddhism was originally introduced to Korea from China in 372, and eventually arrived in Japan around the turn of the 6th century.

For a long time Buddhism remained a foreign religion with a few believers in China. During the Tang dynasty, a fair amount of translations from Sanskrit into Chinese were done by Chinese priests, and Buddhism became one of the major religions of the Chinese along with the other two indigenous religions. In Korea, Buddhism was not seen to conflict with the rites of nature worship; it was allowed to blend in with Shamanism. Thus, the mountains that were believed to be the residence of spirits in pre-Buddhist times became the sites of Buddhist temples. Though Buddhism initially enjoyed wide acceptance, even being supported as the state ideology during the Goguryeo, Silla, Baekje, Balhae, and Goryeo periods, Buddhism in Korea suffered extreme repression during the Joseon dynasty.

In Japan, Buddhism and Shinto were combined using the theological theory "Ryōbushintō", which says Shinto deities are avatars of various Buddhist entities, including Buddhas and Bodhisattvas (Shinbutsu-shūgō). This became the mainstream notion of Japanese religion. In fact until the Meiji government declared their separation in the mid-19th century, many Japanese people believed that Buddhism and Shinto were one religion.

In Mongolia, Buddhism flourished two times; first in the Mongol Empire (13th–14th centuries), and finally in the Qing dynasty (16th–19th centuries) from Tibet in the last 2000 years. It was mixed in with Tengeriism and Shamanism.

Sui dynasty

In AD 581, Yang Jian overthrew the Northern Zhou, and established the Sui dynasty. Later, Yang Jian, who became Sui Wendi, conquered the Chen dynasty, and united China. However, this dynasty was short-lived. Sui Wendi's successor, Sui Yangdi, expanded the Grand Canal, and launched four disastrous wars against the Goguryeo. These projects depleted the resources and the workforce of the Sui. In AD 618, Sui Yangdi was murdered. Li Yuan, the former governor of Taiyuan, declared himself the emperor, and founded the Tang dynasty.

Spread of civil service

A government system supported by a large class of Confucian literati selected through civil service examinations was perfected under Tang rule. This competitive procedure was designed to draw the best talents into government. But perhaps an even greater consideration for the Tang rulers, aware that imperial dependence on powerful aristocratic families and warlords would have destabilizing consequences, was to create a body of career officials having no autonomous territorial or functional power base. As it turned out, these scholar-officials acquired status in their local communities, family ties, and shared values that connected them to the imperial court. From Tang times until the closing days of the Qing dynasty in 1911–1912, scholar officials often functioned often as between the grassroots level and the government. This model of government had an influence on Japan and Korea.

Medieval history (1000-1450)

Goryeo

Silla slowly began to decline and the power vacuum this created led to several rebellious states rising up and taking on the old historical names of Korea's ancient kingdoms. Gyeon Hwon, a peasant leader and Silla army officer, taking over the old territory of Baekje and declared himself the king of Hubaekje ("later Baekje"). Meanwhile, an aristocratic Buddhist monk leader, Gung Ye, declared a new Goguryeo state in the north, known as Later Goguryeo (Hugoguryo). There then followed a protracted power struggle for control of the peninsula.

Gung Ye began to refer to himself as the Buddha, began to persecute people who expressed their opposition against his religious arguments. He executed many monks, then later even his own wife and two sons, and the public began to turn away from him. His costly rituals and harsh rule caused even more opposition. He also moved the capital in 905, changed the name of his kingdom to Majin in 904 then Taebong in 911. In 918, Gung Ye was deposed by his own generals, and Wang Geon, the previous chief minister was raised to the throne. Gung Ye is said to have escaped the palace, but was killed shortly thereafter either by a soldier or by peasants who mistook him for a thief.[24] Wang Geon, who would posthumously be known by his temple name of Taejo of Goryeo.

Soon thereafter, the Goryeo dynasty was proclaimed, and Taejo went on to defeat the rivaling Silla and Hubaekje to reunite the three kingdoms in 936.[25] Following the destruction of Balhae by the Khitan Liao dynasty in 927, the last crown prince of Balhae and much of the ruling class sought refuge in Goryeo, where they were warmly welcomed and given land by Taejo. In addition, Taejo included the Balhae crown prince in the Goryeo royal family, unifying the two successor states of Goguryeo and, according to Korean historians, achieving a "true national unification" of Korea.[26][27]

Mongol Empire and Yuan dynasty

In the early 13th century Genghis Khan united warring Mongol tribes into the united Mongol Empire in 1206. The Mongols would proceed to conquer the majority of modern East Asia. Meanwhile, China were divided into five competing states. From 1211, Mongol forces invaded North China. In 1227 the Mongol Empire conquered Western Xia. In 1234, Ogedei Khan extinguished the Jin dynasty.

The northern part of China was annexed by Mongol Empire. In 1231, the Mongols began to invade Korea, and quickly captured all the territory of the Goryeo outside the southernmost tip. The Goryeo royal family retreated to the sea outside the city of Seoul to Ganghwa Island. Goryeo was divided between collaborators and resisters to the invaders. However, at the time, the Goryeo Sannotei on the peninsula resisted until 1275.

In the 1250s, the Mongols invaded the last remaining state in southern China – the Southern Song. The invasion carried on for over thirty years, and likely resulted in millions of casualties. In 1271, Kublai Khan proclaimed the Yuan dynasty of China in the traditional Chinese style.[28] The last remnants of the Song were defeated at sea in 1279. China was unified under the Yuan dynasty. Kublai Khan and his administration shifted to the Central Plains area and embraced Confucianism.

By 1275, Goryeo had surrendered to the Yuan dynasty as a vassal. Members of the Goryeo royal family were raised to understand Mongol culture, and intermarried with the Yuan imperial family.

Japan was seriously threatened by the Yuan forces from the East Asian mainland. In 1274, Kublai Khan appointed Yudu. In order to recruit Marshal Dongdu to command the Yuan forces, Han Bing and the Goryeo army began the first expedition to Japan. The Yuan dynasty invaded Japan in two separate invasions, both of which were disrupted by natural typhoons. These two invasions both occupied the town of Kitakyushu before being swept into the sea. At the time the Yuan dynasty fleet was the largest fleet in the history of the world.

In order to cope with the nationwide mobilization of the powerful Yuan army, Japan's economy and military were placed under severe pressure. The Japanese Kamakura Shogunate had difficulty compensating its soldiers who had defended the country, which intensified the contradiction between the domestic warrior groups. The ruling system collapsed in the first half of the 14th century[citation needed].

Science and technology

Gunpowder

Most sources credit the discovery of gunpowder to Chinese alchemists in the 9th century searching for an elixir of immortality.[29] The discovery of gunpowder was probably the product of centuries of alchemical experimentation.[30] Saltpetre was known to the Chinese by the mid-1st century AD and there is strong evidence of the use of saltpetre and sulfur in various largely medicine combinations.[31] A Chinese alchemical text from 492 noted that saltpeter gave off a purple flame when ignited, providing for the first time a practical and reliable means of distinguishing it from other inorganic salts, making it possible to evaluate and compare purification techniques.[30] By most accounts, the earliest Arabic and Latin descriptions of the purification of saltpeter do not appear until the 13th century.[30][32]

The first reference to gunpowder is probably a passage in the Zhenyuan miaodao yaolüe, a Taoism text tentatively dated to the mid-9th century:[30] {{blockquote|text=Some have heated together sulfur, realgar and saltpeter with honey; smoke and flames result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house where they were working burned down.[33]

The earliest surviving recipes for gunpowder can be found in the Chinese military treatise Wujing zongyao of 1044 AD,[30] which contains three: two for use in incendiary bombs to be thrown by siege engines and one intended as fuel for poison smoke bombs.[34] The formulas in the Wujing zongyao range from 27 to 50 percent nitrate.[35] Experimenting with different levels of saltpetre content eventually produced bombs, grenades, and land mines, in addition to giving fire arrows a new lease on life.[30] By the end of the 12th century, there were cast iron grenades filled with gunpowder formulations capable of bursting through their metal containers.[36] The 14th century Huolongjing contains gunpowder recipes with nitrate levels ranging from 12 to 91 percent, six of which approach the theoretical composition for maximal explosive force.[35]

In China, the 13th century saw the beginnings of rocketry[37][38] and the manufacture of the oldest gun still in existence,[30][39] a descendant of the earlier fire-lance, a gunpowder-fueled flamethrower that could shoot shrapnel along with fire. The Huolongjing text of the 14th century also describes hollow, gunpowder-packed exploding cannonballs.[40]

In the 13th century contemporary documentation shows gunpowder beginning to spread from China by the Mongols to the rest of the world, starting with Europe[32] and the Islamic world.[41] The Arabs acquired knowledge of saltpetre – which they called "Chinese snow" (Arabic: ثلج الصين thalj al-ṣīn) – around 1240 and, soon afterward, of gunpowder; they also learned of fireworks ("Chinese flowers") and rockets ("Chinese arrows").[41][42] Persians called saltpeter "Chinese salt"[43][44][45][46][47] or "salt from Chinese salt marshes" (namak shūra chīnī Persian: نمک شوره چيني).[48][49] Historian Ahmad Y. al-Hassan argues – contra the general notion – that the Chinese technology passed through Arabic alchemy and chemistry before the 13th century.[50] Gunpowder arrived in India by the mid-14th century, but could have been introduced by the Mongols perhaps as early as the mid-13th century.[51]

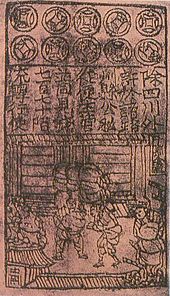

Printing

The first known movable type system was invented in China around 1040 AD by Pi Sheng (990–1051) (spelled Bi Sheng in the Pinyin system).[52] Pi Sheng's type was made of baked clay, as described by the Chinese scholar Shen Kuo (1031–1095). The world's first metal-based movable type was invented in Korea in 1234, 210 years before Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in Germany. Jikji is the world's oldest extant movable metal print book. It was published in Heungdeok Temple in 1377, 78 years prior to Gutenberg's "42-Line Bible" printed during the years 1452–1455.

Early modern history (1450-1750)

Ming dynasty: 1368–1644

The Ming period is the only era of later imperial history during which all of China proper was ruled by ethnic Han. All the counties in China had a county government, a Confucian school, and the standard Chinese family system. Typically the dominant local elite consisted of high status families composed of the gentry owners and managers of land and of other forms of wealth, as well as smaller groups that were subject to elite domination and protection. Much attention was paid to genealogy to prove that high status was inherited from generations back. Substantial land holdings were directly managed by the owning families in the early Ming period, but toward the end of the era marketing and ownership were depersonalized by the increased circulation of silver as money, and estate management gravitated into the hands of hired bailiffs. Together with the departure of the most talented youth into the imperial service, the result was direct contacts between the elite and subject groups were disrupted, and romantic images of country life disappeared from the literature. In villages across China elite families participated in the life of the empire by sending their sons into the very high status imperial civil service. Most of the successful sons had a common education in the county and prefectural schools, had been recruited by competitive examination, and were posted to offices that might be anywhere in the empire, including the imperial capital. At first the recommendation of an elite local sponsor was important; increasing the imperial government relied more on merit exams, and thus entry into the national ruling class became more difficult. Downward social mobility into the peasantry was possible for less successful sons; upward mobility from the peasant class was unheard of.[53]

Qing dynasty: 1644–1912

The Manchus (a tribe from Manchuria) conquered the Shun dynasty (which was established after the Ming fell due to a peasant rebellion) around 1644–1683 in wars that killed perhaps 25 million people. The Manchus ruled it as the Qing dynasty until the early 20th century. Notably, Han men were forced to wear the long queue (or pigtail) as a mark of their inferior status. That said, some Han did achieve high rank in the civil service via the Imperial Examination system. Until the 19th century, Han immigration into Manchuria was forbidden. Chinese had an advanced artistic culture and well-developed science and technology. However, its science and technology stood still after 1700 and in the 21st century very little survives outside museums and remote villages, except in for the ever-popular forms of traditional medicine like acupuncture. In the late Qing era (1900 to 1911), the country was beset by large-scale civil wars, major famines, military defeats by Britain and Japan, regional control by powerful warlords and foreign intervention such as the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. Final collapse came in 1911.[54]

Military success in 18th century

The Ten Great Campaigns of the Qianlong Emperor from the 1750s to the 1790s extended Qing control into Inner Asia. During the peak of the Qing dynasty, the empire ruled over the entirety of today's Mainland China, Hainan, Taiwan, Mongolia, Outer Manchuria and areas outside today's Northwest China.[55]

Military defeats in 19th century

Despite its origin in military conquest, and the long warlike tradition of the Manchu people who formed its ruling class, by the 19th century the Qing state was militarily extremely weak, poorly trained, lacking modern weapons and plagued by corruption and incompetence.[55]

They repeatedly lost against the Western powers. Two Opium Wars (鸦片战争 yāpiàn zhànzhēng), pitted China against Western powers, notably Britain and France. China quickly lost both wars. After each defeat, the victors forced the Chinese government to make major concessions. After the first war 1839–1842, the treaty ceded Hong Kong island to Britain, and opened five "treaty ports" including Shanghai and Guangzhou (Canton), and others of less importance Xiamen, Fuzhou, and Ningbo) to Western trade. After the second, Britain acquired Kowloon (the peninsula opposite Hong Kong island), and inland cities such as Nanjing and Hangkou (now part of Wuhan) were opened to trade.[56]

Defeat in the Second Opium War, 1856–1860, was utterly humiliating for China. The British and French sent ambassadors, escorted by a small army, to Beijing to see the treaty signed. The Emperor, however, did not receive ambassadors in anything like the Western sense; the closest Chinese expression translates as "tribute-bearer". To the Chinese court, Western envoys were just a group of new outsiders who should show appropriate respect for the emperor like any other visitors; of course the kowtow (knocking one's head on the floor) was a required part of the protocol. For that matter, the kowtow was required in dealing with any Chinese official. From the viewpoint of Western powers, treating China's decadent medieval regime with any respect at all was being generous. The envoy of Queen Victoria or another power might give some courtesies, even pretend for form's sake that the Emperor was the equal of their own ruler. However, they considered the notion that they should kowtow utterly ludicrous. In fact, it was official policy that no Briton of any rank should kowtow in any circumstances.

China engaged in various stalling tactics to avoid actually signing the humiliating treaty to which their envoys had already agreed, and the scandalous possibility of an envoy coming before the Emperor and failing to kowtow. The ambassadors' progress to Beijing was impeded at every step. Several battles were fought, in each of which Chinese forces were soundly thrashed by numerically inferior Western forces. Eventually, Beijing was occupied, the treaty signed and embassies established. The British took the luxurious house of a Manchu general prominent in opposing their advance as their embassy.

In retaliation for Chinese torture and murder of captives, including envoys taken while under a flag of truce, British and French forces also utterly destroyed the Yuan Ming Yuan (Old Summer Palace), an enormous complex of gardens and buildings outside Beijing. It took 3500 troops to loot it, wreck it and set it alight, and it burned for three days sending up a column of smoke clearly visible in Beijing. Once the Summer Palace was reduced to ruins a sign was raised with an inscription in Chinese stating "This is the reward for perfidy and cruelty". The choice to destroy the palace was quite deliberate; they wanted something quite visible that struck at the upper classes who had ordered the crimes. Like the Forbidden City, no ordinary Chinese citizen had ever been allowed into the Summer Palace, as it was used exclusively by the Imperial family.[57]

In 1884–1885, China and France fought a war that resulted in China's accepting French control over their former tributary states in what is now Vietnam. The Qing armies acquitted themselves well in campaigns in Guangxi and Taiwan. However, the French sank much of China's modernized Fuzhou-based naval fleet in an afternoon.

They also lost repeatedly against Japan, partly because Britain had helped modernise Japanese forces as a counter to Russian influence in the region.[citation needed] In 1879, Japan annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom, then a Chinese tributary state, and incorporated it as Okinawa prefecture. Despite pleas from a Ryukyuan envoy, China was powerless to send an army. The Chinese sought help from the British, who refused to intervene. In 1895, China lost the Sino-Japanese war and ceded Taiwan, the Penghu islands and the Liaodong peninsula to Japan. In addition, it had to relinquish control of Korea, which had been a tributary state of China for a long time.

Rebellions

The Qing also had internal troubles, notably several Muslim rebellions in the West and the Taiping Rebellion in the South, with millions dead and tens of millions more impoverished.

The Taiping Rebellion, 1851–1864, was led by a charismatic figure claiming to be Christ's younger brother. It was largely a peasant revolt. The Taiping program included land reform and eliminating slavery, concubinage, arranged marriage, opium, footbinding, judicial torture and idolatry. The Qing government, with some Western help, eventually defeated the Taiping rebels, but not before they had ruled much of southern China for over ten years. This was one of the bloodiest wars ever fought; only World War II killed more people.[58]

The Chinese resented much during this period — notably Christian missionaries, opium, annexation of Chinese land and the extraterritoriality that made foreigners immune to Chinese law. To the West, trade and missionaries were obviously good things, and extraterritoriality was necessary to protect their citizens from the corrupt Chinese system. To many Chinese, however, these were yet more examples of the West exploiting China.[59]

Boxer Rebellion 1898–1900

Around 1898, these feelings exploded. The Boxers, also known as the "Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists" (义和团 yì hé tuán) led a peasant religious/political movement whose main goal was to drive out evil foreign influences. Some believed their kung fu and prayer could stop bullets. While initially anti-Qing, once the revolt began they received some support from the Qing court and regional officials. The Boxers killed a few missionaries and many Chinese Christians, and eventually besieged the embassies in Beijing. An eight-nation alliance — Germany, France, Italy, Russia, Great Britain, the United States, Austria-Hungary and Japan — sent a force up from Tianjin to rescue the legations. The Qing had to accept foreign troops permanently posted in Beijing and pay a large indemnity as a result. In addition, Shanghai was divided among China and the eight nations.[60][61][62]

Last minute reforms 1898–1908

The Hundred Days' Reform was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement in 1898. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu Emperor and his reform-minded supporters. Following the issuing of the reformative edicts, a coup d'état ("The Coup of 1898", Wuxu Coup) was perpetrated by powerful conservative opponents led by Empress Dowager Cixi, who became a virtual dictator.[63]

The Boxer Rebellion was a humiliating fiasco for China: the Qing rulers proved visibly incompetent and lost prestige irreparably, while the foreign powers gained greater influence in Chinese affairs. The humiliation stimulated a second reform movement—this time sanctioned by the empress dowager Cixi herself. From 1901 to 1908, the dynasty announced a series of educational, military, and administrative reforms, many reminiscent of the "one hundreds days" of 1898. In 1905 the examination system itself was abolished and the entire Confucian tradition of merit entry into the elite collapsed. The abolition of the traditional civil service examination was itself a revolution of immense significance. After many centuries, the scholar's mind began to be liberated from the shackles of classical studies, and social mobility no longer depended chiefly on the writing of stereotyped and flowery prose. New ministries were created in Beijing and revised law codes were drafted. Work began on a national budget—the national government had no idea how much taxes were collected in its name and spent by regional officials. New armies were raised and trained in European (and Japanese) fashion and plans for a national army were laid. The creation of the "new army" reflected rising esteem for the military profession and the emergence of a new national elite that dominated China for much of the 20th century. . More officers and men were now literate, while patriotism and better pay served as an inducement for service.[64]

Reform and revolution

The movement for constitutionalism gathered momentum following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, for Japan's victory signalled the triumph of constitutionalism over absolutism. Under pressure from gentry and student groups, the Qing court in 1908 issued plans for the inauguration of consultative provincial assemblies in 1909, a consultative national assembly in 1910, and both a constitution and a parliament in 1917. The consultative assemblies were to play a pivotal role in the unfolding events, politicizing the provincial gentry and providing them with new leverage with which to protect their interests.[65]

Ironically, the measures designed to preserve the Qing dynasty hastened its death, for the nationalistic and modernizing impulses generated or nurtured by the reforms brought a greater awareness of the Qing government's extreme backwardness. Modernizing forces emerged as business, students, women, soldiers, and overseas Chinese became mobilized and demanded change. Government-sponsored education in Japan, available to both civilian and military students, exposed Chinese youths to revolutionary ideas produced by political exiles and inspired by the West. Anti-Manchu revolutionary groups were formed in the Yangtze cities by 1903, and those in Tokyo banded together to form the "Revolutionary Alliance" in 1905, led by Sun Yat-sen.[66]

Joseon Korea: 1392–1897

In July 1392, General Yi Seong-gye overthrew the Goryeo dynasty and founded a new dynasty, Joseon. As King Taejo of Joseon, he chose Hanyang (Seoul) as the capital of the new dynasty. During its 500-year reign, Joseon encouraged the entrenchment of Confucian ideals and doctrines in Korean society. Neo-Confucianism was installed as the new dynasty's state ideology. Joseon consolidated its effective rule over the territory of current Korea and saw the height of classical Korean culture, trade, literature, and science and technology. Joseon dynasty was a highly centralized monarchy and neo-Confucian bureaucracy as codified by Gyeongguk daejeon, a sort of Joseon constitution. The king had absolute authority, the officials were also expected to persuade the king to the right path if the latter was thought to be mistaken. He was bound by tradition, precedents set by earlier kings, Gyeongguk daejeon, and Confucian teachings. In theory, there were three social classes, but in practice, there were four. The top class were the yangban, or "scholar-gentry",[67] the commoners were called sangmin or yangmin, and the lowest class was that of the cheonmin.[68] Between the yangban and the commoners was a fourth class, the chungin, "middle people".[69] Joseon Korea installed a centralised administrative system controlled by civil bureaucrats and military officers who were collectively called Yangban. Yangban strove to do well at the royal examinations to obtain high positions in the government. They had to excel in calligraphy, poetry, classical Chinese texts, and Confucian rites. In order to become an official, one had to pass a series of gwageo examinations. There were three kinds of gwageo exams – literary, military, and miscellaneous.

Edo Japan

In 1603, the Tokugawa shogunate (military dictatorship) ushered in a long period of isolation from foreign influence in order to secure its power. For 250 years this policy enabled Japan to enjoy stability and a flowering of its indigenous culture. Early modern Japanese society had an elaborate social structure, in which everyone knew their place and level of prestige. At the top were the emperor and the court nobility, invincible in prestige but weak in power. Next came the "bushi" of shōgun, daimyō and layers of feudal lords whose rank was indicated by their closeness to the Tokugawa. They had power. The "daimyō" were about 250 local lords of local "han" with annual outputs of 50,000 or more bushels of rice. The upper strata was much given to elaborate and expensive rituals, including elegant architecture, landscaped gardens, nō drama, patronage of the arts, and the tea ceremony.

Three cultures

Three distinct cultural traditions operated during the Tokugawa era, having little to do with each other. In the villages the peasants had their own rituals and localistic traditions. In the high society of the imperial court, daimyō and samurai, Chinese cultural influence was paramount, especially in the areas of ethics and political ideals. Neo-Confucianism became the approved philosophy, and was taught in official schools; Confucian norms regarding personal duty and family honor became deeply implanted in elite thought. Equally pervasive was the Chinese influence in painting, decorative arts and history, economics, and natural science. One exception came in religion, where there was a revival of Shinto, which had originated in Japan. Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801) freed Shinto from centuries of Buddhist accretions and gave a new emphasis to the myth of imperial divine descent, which later became a political tool for imperialist conquest until it was destroyed in 1945. The third cultural level was the popular art of the low-status artisans, merchants and entertainers, especially in Edo and other cities. It revolved around "ukiyo", the floating world of the city pleasure quarters and theaters that was officially off-limits to samurai. Its actors and courtesans were favorite subjects of the woodblock color prints that reached high levels of technical and artistic achievement in the 18th century. They also appeared in the novels and short stories of popular prose writers of the age like Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693). The theater itself, both in the puppet drama and the newer kabuki, as written by the greatest dramatist, Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724), relied on the clash between duty and inclination in the context of revenge and love.

Growth of Edo/Tokyo

Edo (Tokyo) had been a small settlement for 400 years but began to grow rapidly after 1603 when Shōgun Ieyasu built a fortified city as the administrative center of the new Tokugawa Shogunate. Edo resembled the capital cities of Europe with military, political, and economic functions. The Tokugawa political system rested on both feudal and bureaucratic controls, so that Edo lacked a unitary administration. The typical urban social order was composed of samurai, unskilled workers and servants, artisans, and businessmen. The artisans and businessmen were organized in officially sanctioned guilds; their numbers grew rapidly as Tokyo grew and became a national trading center. Businessmen were excluded from government office, and in response they created their own subculture of entertainment, making Edo a cultural as well as a political and economic center. With the Meiji Restoration, Tokyo's political, economic, and cultural functions simply continued as the new capital of imperial Japan.

Western colonialism (1750-1919)

The Meiji Era

Following the Treaty of Kanagawa with the United States of America in 1854, Japan opened its ports and began to intensively modernise and industrialise. The Meiji Restoration of 1868 ended the Tokugawa period, and put Japan on a course of centralized modern government in the name of the Emperor. During late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Japan became a regional power that was able to defeat the militaries of both China and Russia. It occupied Korea, Formosa (Taiwan), and southern Sakhalin Island.

Early 20th century (1900-1950)

Pacific War

In 1931, Japan occupied Manchuria ("Dongbei") after the Manchurian Incident, and in 1937 it launched a full-scale invasion of China. The U.S. undertook large scale military and economic aid to China and demanded Japanese withdrawal. Instead of withdrawing, Japan invaded French Indochina in 1940–41. In response, the U.S., Britain and the Netherlands cut off oil imports in 1941, which accounted for over 90% of Japan's oil supply. Negotiations with the US led nowhere. Japan attacked U.S. forces at the Battle of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, triggering America's entry into World War II. Japan rapidly expanded at sea and land, capturing Singapore and the Philippines in early 1942, and threatening India and Australia.

Although it was to be a long and bloody war, Japan began to lose the initiative in 1942. At the Battle of the Coral Sea, a Japanese offensive was turned back, for the first time, at sea. The June Battle of Midway cost Japan four of its six large aircraft carriers and destroyed its capability for future major offensives. In the Guadalcanal Campaign, the U.S. took back ground from Japan.

U.S. occupation of Japan

After its defeat in World War II, Japan was occupied by the U.S. until 1951, and recovered from the effects of the war to become an economic power, staunch American ally and a liberal democracy. While Emperor Hirohito was allowed to retain his throne as a symbol of national unity, actual power rests in networks of powerful politicians, bureaucrats, and business executives.

Contemporary era

Cold War

The Japanese growth in the postwar period was often called a "miracle". It was led by manufacturing; starting with textiles and clothing and moving to high-technology, especially automobiles, electronics and computers. The economy experienced a major slowdown starting in the 1990s following three decades of unprecedented growth, but Japan still remains a major global economic power.[70]

The Chinese Civil War resumed after World War II concluded. In 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China, which had governed mainland China until this point, retreated to Taiwan. Since then, the jurisdiction of the Republic of China has been limited to the Taiwan Area.[71][72]

After the surrender of Japan, at the end of World War II, on 15 August (officially 2 September) 1945, Korea was divided at the 38th parallel into two zones of occupation. The Soviets administered the northern-half and the Americans administered the southern-half. In 1948, as a result of Cold War tensions, the occupation zones became two sovereign states. This led to the establishment of the Republic of Korea in South Korea on 15 August 1948, promptly followed by the establishment of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea in North Korea on 9 September 1948. In 1950, after years of mutual hostilities, North Korea invaded South Korea in an attempt to re-unify the peninsula under its communist rule. The united Nations, under the leadership of the United States, back, and China entered to protect North Korea. The Korean War, which lasted from 1950 to 1953, ended with a stalemate and has left the two Koreas separated by the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) up to the present day.[73]

Decline of religion

Historically, cultures and regions strongly influenced by Confucianism include Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Japan, North Korea, and South Korea, as well as territories settled predominantly by Overseas Chinese, such as Singapore. The abolition of the examination system in 1905 marked the end of official Confucianism. The New culture intellectuals of the early twentieth century blamed Confucianism for China's weaknesses. They searched for new doctrines to replace Confucianism, some of these new ideologies include the "Three Principles of the People" with the establishment of the Republic of China, and then Maoism under the People's Republic of China.

In Japan, the presence of a liberal order and consumerism led to a voluntarily decline of religious belief.

Around the turn of the 21st century there were talks of a "Confucian Revival" in the academia and the scholarly community.[74][75] Across the region cultural institutions of religions have remained, even while actual belief has declined.

Maps

|

|

See also

- East Asia–United States relations

- History of Asia

- History of China

- History of Hong Kong

- History of Japan

- History of Korea

- History of Mongolia

- History of Taiwan

References

- ^ a b Holcombe, Charles (2017). A history of East Asia: from the origins of civilization to the twenty-first century (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-11873-7.

- ^ a b Austin, Gareth (2017). Economic Development and Environmental History in the Anthropocene: Perspectives on Asia and Africa. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-4742-6749-6.

- ^ "A Brief History of East Asian Studies at Yale University". Council on East Asian Studies at Yale University. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- ^ a b Morris-Suzuki, Tessa; Low, Morris; Petrov, Leonid; Tsu, Timothy (2013). East Asia Beyond the History Wars: Confronting the Ghosts of Violence. Oxon: Routledge. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-415-63745-9.

- ^ Park, Hye Jeong (2014). "East Asian Odyssey towards One Region: The Problem of East Asia as a Historiographical Category". History Compass. 12 (12): 889–900. doi:10.1111/hic3.12209. ISSN 1478-0542.

- ^ Abalahin, Andrew J. (2011). ""Sino-Pacifica": Conceptualizing Greater Southeast Asia as a Sub-Arena of World History". Journal of World History. 22 (4): 659–691. ISSN 1045-6007. JSTOR 41508014.

Conventional geography's boundary line between a "Southeast Asia" and an "East Asia," following a "civilizational" divide between a "Confucian" sphere and a "Vietnam aside, everything but Confucian" zone, obscures the essential unity of the two regions.

- ^ "Key Points across East Asia—by Era 4000 BCE-1000 CE". Asia for Educators. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ "Population of Eastern Asia". www.worldometers.info. Worldometers. 2018. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- ^ Peking Man Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine. The History of Human Evolution. American Museum of Natural History. April 23, 2014.

- ^ Homo erectus. London: Natural History Museum. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ By Land and Sea. Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ Steppes into Asia. Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ Yang, X.; Wan, Z.; Perry, L.; Lu, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, C.; Li, J.; Xie, F.; Yu, J.; Cui, T.; Wang, T.; Li, M.; Ge, Q. (2012). "Early millet use in northern China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (10): 3726–3730. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.3726Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115430109. PMC 3309722. PMID 22355109.

- ^ a b Lee 2001.

- ^ Lee 2006.

- ^ "Public Summary Request Of The People's Republic Of China To The Government Of The United States Of America Under Article 9 Of The 1970 Unesco Convention". Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. State Department. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ^ "The Ancient Dynasties". University of Maryland. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ^ Craig 1998, p. 550.

- ^ Robinet 1997, p. 54.

- ^ Robinet 1997, p. 1.

- ^ Robinet 1997, p. 50.

- ^ Robinet 1997, p. 184.

- ^ Robinet 1997, p. 115.

- ^ Joanna Rurarz (2009). Historia Korei. Dialog. p. 145. ISBN 978-83-89899-28-6.

- ^ "Taejo". Doosan Encyclopedia (in Korean). Archived from the original on 2023-08-10.

- ^ Kim 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Lee 1984, p. 103.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis C.; Franke, Herbert. "Chinese society under Mongol rule, 1215–1368". The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 6. p. 624. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243315.011. ISBN 9780521243315.

- ^ Bhattacharya (in Buchanan 2006, p. 42) acknowledges that "most sources credit the Chinese with the discovery of gunpowder" though he himself disagrees.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chase 2003, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Buchanan. "Editor's Introduction: Setting the Context", in Buchanan 2006.

- ^ a b Kelly 2004, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 10.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, pp. 345–346.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 347.

- ^ Crosby 2002, pp. 100–103.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 12.

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 264.

- ^ a b Urbanski 1967, Chapter III: Blackpowder.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 108.

- ^ Watson, Peter (2006). Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud. HarperCollins. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1.

The first use of a metal tube in this context was made around 1280 in the wars between the Song and the Mongols, where a new term, chong, was invented to describe the new horror...Like paper, it reached the West via the Muslims, in this case the writings of the Andalusian botanist Ibn al-Baytar, who died in Damascus in 1248. The Arabic term for saltpetre is 'Chinese snow' while the Persian usage is 'Chinese salt'.28

- ^ Cathal J. Nolan (2006). The age of wars of religion, 1000–1650: an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization. Vol. 1 of Greenwood encyclopedias of modern world wars. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-313-33733-8. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

In either case, there is linguistic evidence of Chinese origins of the technology: in Damascus, Arabs called the saltpeter used in making gunpowder " Chinese snow," while in Iran it was called "Chinese salt." Whatever the migratory route

- ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1970). Artillery: its origin, heyday, and decline. Archon Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-208-01040-7.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese Snow and employed it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

- ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1963). English artillery, 1326–1716: being the history of artillery in this country prior to the formation of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. Royal Artillery Institution. p. 42.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese Snow and employed it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

- ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1993). Clubs to cannon: warfare and weapons before the introduction of gunpowder (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-56619-364-1. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese snow and used it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

- ^ Partington, J.R. (1960). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder (illustrated, reprint ed.). JHU Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Yu, Ping-Yu (1980). Needham, Joseph (ed.). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts. Vol. 5. Contributors Joseph Needham, Lu Gwei-Djen, Nathan Sivin (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-521-08573-1. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ^ al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources". History of Science and Technology in Islam. Archived from the original on 2008-02-26. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 130.

- ^ Needham & Tsuen-Hsuin 1985, p. 201.

- ^ John W. Dardess, Ming China, 1368–1644: A Concise History of a Resilient Empire (2011). excerpt

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman 2006, pp. 163–254.

- ^ a b Fairbank & Goldman 2006, pp. 143–162.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman 2006, pp. 187–205.

- ^ Henry Loch (1869), Personal narrative of occurrences during Lord Elgin's second embassy to China, 1860

- ^ Hsü 1990, pp. 221–253.

- ^ Chin Shunshin and Joshua A. Fogel, The Taiping Rebellion (Routledge, 2018).

- ^ Hsü 1990, pp. 387–407.

- ^ Diana Preston, The Boxer Rebellion: The Dramatic story of China's war on foreigners that shook the world in the summer of 1900 (Bloomsbury, 2000).

- ^ Sven Lange (de), Revolt Against the West: A Comparison of the Boxer Rebellion of 1900–1901 and the Current War against Terror (Naval Postgraduate School, Defense Technical Information Center, 2004) online free

- ^ Wong, Young-Tsu (1992). "Revisionism Reconsidered: Kang Youwei and the Reform Movement of 1898". The Journal of Asian Studies. 51 (3): 513–544. doi:10.2307/2057948. JSTOR 2057948. S2CID 154815023.

- ^ Hsü 1999, pp. 408–418.

- ^ Jonathan D. Spence, The Search for Modern China (3rd ed. 2012) pp 245-658.

- ^ Rana Mitter, "1911: The Unanchored Chinese Revolution." The China Quarterly 208 (2011): 1009–1020.

- ^ Nahm 1996, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Seth 2010, pp. 165–167.

- ^ Seth 2010, p. 170.

- ^ Xiaobing Li, . The Cold War in East Asia (Routledge, 2017)

- ^ Sarmento, Clara (2009). Eastwards / Westwards: Which Direction for Gender Studies in the 21st Century?. Cambridge Scholars. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-4438-0868-2.

- ^ Henckaerts, Jean-Marie (1996). The International Status of Taiwan in the New World Order: Legal And Political Considerations. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 978-90-411-0929-3.

- ^ William Stueck, The Korean War: an international history (Princeton University Press, 1997).

- ^ Benjamin Elman, John Duncan and Herman Ooms ed. Rethinking Confucianism: Past and Present in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian Pacific Monograph Series, 2002).

- ^ Yu Yingshi, Xiandai Ruxue Lun (River Edge: Global Publishing Co. Inc. 1996).

Works cited

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006), Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History, Aldershot: Ashgate, ISBN 978-0-7546-5259-5

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9

- Craig, Edward (1998), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, vol. 7, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9780415073103

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-79158-8

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006), China: A New History (2nd ed.)

- Hsü, Immanuel C. (1990), The Rise of Modern China

- Hsü, Immanuel C. (1999), The Rise of Modern China (6th ed.), Oxford University Press

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-03718-6

- Kim, Jinwung (2012), A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict, Indiana University Press, ISBN 9780253000248

- Lee, June-Jeong (2001). From Shellfish Gathering to Agriculture in Prehistoric Korea: The Chulmun to Mumun Transition (PhD thesis). University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Lee, June-Jeong (2006). "From Fisher-Hunter to Farmer: Changing Socioeconomy during the Chulmun Period in Southeastern Korea". In Grier, Colin; Kim, Jangsuk; Uchiyama, Junzo (eds.). Beyond "Affluent Foragers": The Development of Fisher-Hunter Societies in Temperate Regions. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Lee, Ki-baik (1984), A New History of Korea, translated by Wagner, Edward W.; Schultz, Edward J., Harvard University Press, ISBN 9780674615762

- Nahm, Andrew C. (1996). Korea: Tradition and Transformation — A History of the Korean People (2nd ed.). Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International. ISBN 1-56591-070-2.

- Needham, Joseph; Tsuen-Hsuin, Tsien (1985), Science & Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Part 1: Paper and Printing, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08690-5

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Part 7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3

- Robinet, Isabelle (1997). Taoism: Growth of a Religion. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2839-9.

- Seth, Michael J. (2010). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742567177.

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, vol. III, New York: Pergamon Press

Further reading

- Buss, Claude A. The Far East A History Of Recent And Contemporary International Relations In East Asia (1955) online free

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, and Anne Walthall. East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History (2 vol. 2008–2013) online free to borrow 703pp

- Embree, Ainslie T., ed. Encyclopedia of Asian history (1988)

- Fitzgerald, C. P. A concise history of East Asia (1966) online free to borrow

- Hamashita, Takeshi. "Changing Regions and China: Historical Perspectives." China Report 37.3 (2001): 333–351. How countries in region related to China in 19th-20th centuries

- Holcombe, Charles. A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century (2010)

- Jansen, Marius B. Japan and China: from war to peace, 1894–1972 (1975).

- Kang, David. East Asia Before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute (Columbia University Press, 2010).

- Li, Xiaobing. The Cold War in East Asia (Routledge, 2017).

- Lipman, Jonathan N. and Barbara A. Molony. Modern East Asia: An Integrated History (2011)

- Miller, David Y. Modern East Asia: An Introductory History (2007).

- Murphey, Rhoads. East Asia: a new history (2001) online free to borrow

- Morris-Suzuki, Tessa; Low, Morris; Petrov, Leonid; Tsu, Timothy. East Asia Beyond the History Wars: Confronting the Ghosts of Violence (2013)

- Paine, S. C. M. The Wars for Asia, 1911–1949 (2014) new approaches to military and diplomatic history of China, Japan & Russia excerpt

- Park, Hye Jeong "East Asian Odyssey towards One Region: The Problem of East Asia as a Historiographical Category". History Compass (2014). 12 (12): 889–900. doi:10.1111/hic3.12209. ISSN 1478-0542.

- Prescott, Anne. East Asia in the World: An Introduction (2015)

- Rozman, Gilbert, and Sergey Radchenko, eds. International Relations and Asia's Northern Tier: Sino-Russia Relations, North Korea, and Mongolia (Springer, 2017).

- Schottenhammer, Angela, ed. (2008). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Vol. 6 of East Asian economic and socio-cultural studies: East Asian maritime history (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Sicilia, David B.; Wittner, David G. Strands of Modernization: The Circulation of Technology and Business Practices in East Asia, 1850-1920 (University of Toronto Press, 2021) online review

- Thorne, Christopher G. The limits of foreign policy; the West, the League, and the Far Eastern crisis of 1931–1933 (1972) online

- Walker, Hugh. East Asia: A New History (2012)

- Zurndorfer, Harriet. "Oceans of history, seas of change: recent revisionist writing in western languages about China and East Asian maritime history during the period 1500–1630." International Journal of Asian Studies 13.1 (2016): 61–94.

Scholarly journals

- Asian Journal of Political Science.

- Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History, In Japanese

- Central Asian Survey

- China Report published in India and covers China and East Asia

- Chinese Studies in History

- East Asian History. Archived from the original on 2017-11-08.

- Journal of American-East Asian Relations

- Journal of Japanese Studies

- Journal of Modern Chinese History

- Journal of Northeast Asian Studies

- Korean Studies

- Late Imperial China

- Modern China. An International Journal of History and Social Science

- Monumenta Nipponica, Japanese studies (in English)

- Sino-Japanese Studies

- Social Science Japan Journal

- T'oung Pao: International Journal of Chinese Studies