East African campaign (World War II)

| East African campaign | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mediterranean and Middle East theatre of the Second World War | |||||||||

South African soldiers with a captured Italian flag, 1941 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 80+ aircraft 2 cruisers 2 destroyers 2 auxiliary cruisers | 323 aircraft 63 tanks 126 armoured cars | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

British Empire: 1,154 killed 74,550 wounded or sick[a] 138 aircraft Ethiopia: 5,000 killed[citation needed] Belgium: 462 killed Free France: 2 aircraft |

Italy: 16,966 killed 25,098 wounded or sick ~230,000 captured 250 aircraft | ||||||||

| AOI casualties exclude Giuba and the eastern front | |||||||||

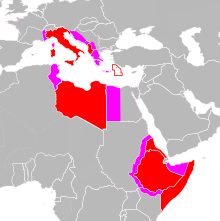

The East African campaign (also known as the Abyssinian campaign) was fought in East Africa during the Second World War by Allies of World War II, mainly from the British Empire, against Italy and its colony of Italian East Africa, between June 1940 and November 1941. The British Middle East Command with troops from the United Kingdom, South Africa, British India, Uganda Protectorate, Kenya, Somaliland, West Africa, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, Sudan and Nyasaland participated in the campaign. These were joined by the Allied Force Publique of Belgian Congo, Imperial Ethiopian Arbegnoch (resistance forces) and a small unit of Free French Forces.

Italian East Africa was defended by the Comando Forze Armate dell'Africa Orientale Italiana (Italian East African Armed Forces Command), with units from the Regio Esercito (Royal Army), Regia Aeronautica (Royal Air Force) and Regia Marina (Royal Navy). The Italian forces included about 250,000 soldiers of the Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali (Royal Corps of Colonial Troops), led by Italian officers and NCOs. With Britain in control of the Suez Canal, the Italian forces were cut off from supplies and reinforcement once hostilities began.

On 13 June 1940, an Italian air raid took place on the RAF base at Wajir in Kenya and the air war continued until Italian forces had been pushed back from Kenya and Sudan, through Somaliland, Eritrea and Ethiopia in 1940 and early 1941. The remnants of the Italian forces in the region surrendered after the Battle of Gondar in November 1941, except for small groups that fought a guerrilla war in Ethiopia against the British until the Armistice of Cassibile in September 1943, which ended the war between Italy and the Allies. The East African campaign was the first Allied strategic victory in the war; few Italian forces escaped the region to be used in other campaigns and the Italian defeat greatly eased the flow of supplies through the Red Sea to Egypt. Most of the Commonwealth forces were transferred to North Africa to participate in the Western Desert campaign.

Background

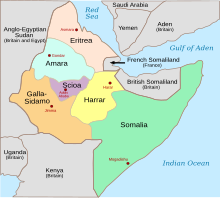

Italian East Africa

On 9 May 1936, the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, proclaimed the formation of Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI), from Ethiopia after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War and the colonies of Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland.[6] On 10 June 1940, Mussolini declared war on Britain and France, which made Italian military forces in Libya a threat to Egypt and those in the AOI a danger to the British and French colonies in East Africa. Italian belligerence also closed the Mediterranean to Allied merchant ships and endangered British sea lanes along the coast of East Africa, the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. (The Kingdom of Egypt remained neutral during the Second World War but the terms of the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936 allowed the British to occupy Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.)[7] Egypt, the Suez Canal, French Somaliland and British Somaliland were also vulnerable to invasion but the Italian General Staff had planned for a war after 1942; in the summer of 1940 Italy was far from ready for a long war or for the occupation of large areas of Africa.[8]

Regio Esercito

Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, was appointed Viceroy and Governor-General of the AOI in November 1937, with a headquarters in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital. On 1 June 1940, as the commander in chief of Comando Forze Armate dell'Africa Orientale Italiana (Italian East African Armed Forces Command) and Generale d'Armata Aerea (General of the Air Force), Aosta had about 290,476 local and metropolitan troops (including naval and air force personnel). By 1 August, mobilisation had increased the number to 371,053 troops.[9] On 10 June, the Italian army was organised in three corps and one division commands,

- Northern Sector, in Asmara, Lieutenant General Luigi Frusci (Italian Eritrea)

- Southern Sector, in Jimma, General Pietro Gazzera

- Eastern Sector, in Addis Ababa, General Guglielmo Nasi

- Giuba Sector, in Mogadishu, Lieutenant General Carlo De Simone (Southern Italian Somaliland)

Aosta had two metropolitan divisions, the 40th Infantry Division "Cacciatori d'Africa" and the 65th Infantry Division "Granatieri di Savoia", the Alpini Battalion "Uork Amba" of the 7th Alpini Regiment Alpini (elite mountain troops), a Bersaglieri battalion of motorised infantry, several Blackshirt Milizia Coloniale battalions and smaller units. About 70 per cent of Italian troops were locally recruited Askari. The regular Eritrean battalions and the Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali (RCTC Royal Corps of Somali Colonial Troops) were among the best Italian units in the AOI and included Eritrean cavalry Penne di Falco (Falcon Feathers).[10] (On one occasion a squadron of horse charged British and Commonwealth troops, throwing small hand grenades from the saddle.) Most colonial troops were recruited, trained and equipped for colonial repression, although the Somali Dubats from the borderlands were useful light infantry and skirmishers. Irregular bande were hardy and mobile, knew the country and were effective scouts and saboteurs, although sometimes confused with Shifta, marauders who plundered and murdered at will.[11]

Once Italy entered the war, a 100-strong company was formed from German residents of East Africa and stranded German sailors.[12] Italian forces in East Africa were equipped with about 3,313 heavy machine-guns, 5,313 machine-guns, 24 M11/39 medium tanks, 39 L3/35 tankettes, 126 armoured cars and 824 guns, twenty-four 20 mm anti-aircraft guns, seventy-one 81 mm mortars and 672,800 rifles.[13] The Italians had little opportunity for reinforcement or supply, leading to severe shortages, especially of ammunition.[14] On occasion, foreign merchant vessels captured by German merchant raiders in the Indian Ocean were brought to Somali ports but their cargoes were not always of much use to the Italian war effort. On 22 November 1940 the Yugoslav steamer Durmitor, captured by the German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis, put in at Warsheikh with a cargo of salt and several hundred prisoners.[15]

Regia Aeronautica

The Comando Aeronautica Africa Orientale Italiana (CAAOI) of the Regia Aeronautica (General Pietro Pinna) based in Addis Ababa, had three sector commands corresponding to the land fronts,

- Comando Settore Aeronautico Nord (Air Sector Headquarters North)

- Comando Settore Aeronautico Est (Air Sector Headquarters West)

- Comando Settore Aeronautico Sud (Air Sector Headquarters South)

In June 1940, there were 323 aircraft in the AOI, in 23 bomber squadrons with 138 aircraft, comprising 14 squadrons with six aircraft each, six Caproni Ca.133 light bomber squadrons, seven Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 squadrons and two squadrons of Savoia-Marchetti SM.79s. Four fighter squadrons had 36 aircraft, comprising two nine-aircraft Fiat CR.32 squadrons and two nine-aircraft Fiat CR.42 Falco squadrons; CAAOI had one reconnaissance squadron with nine IMAM Ro.37 aircraft. There were 183 first line aircraft and another 140 in reserve, of which 59 were operational and 81 were unserviceable.[16][b]

On the outbreak of war, the CAAOI had 10,700 t (10,500 long tons) of aviation fuel, 5,300 t (5,200 long tons) of bombs and 8,620,000 rounds of ammunition. Aircraft and engine maintenance was conducted at the main air bases and at the Caproni and Piaggio workshops, which could repair about fifteen seriously-damaged aircraft and engines each month, along with some moderately and lightly damaged aircraft and could also recycle scarce materials.[16] The Italians had reserves for 75 per cent of their front-line strength but lacked spare parts and many aircraft were cannibalised to keep others operational.[18] The quality of the units varied. The SM.79 was the only modern bomber and the CR.32 fighter was obsolete but the Regia Aeronautica in East Africa had a cadre of highly experienced Spanish Civil War veterans.[19] There was the nucleus of a transport fleet, with nine Savoia-Marchetti S.73, nine Ca.133, six Ca.148 (a lengthened version of the Ca.133) and a Fokker F.VII, which maintained internal communications and carried urgent items and personnel between sectors.[16]

Regia Marina

From 1935 to 1940 the Regia Marina (Italian Royal Navy) laid plans for an ocean-going "escape fleet" (Flotta d'evasione) equipped for service in the tropics. The plans varied from three battleships, an aircraft carrier, twelve cruisers, 36 destroyers and 30 submarines to a more realistic two cruisers, eight destroyers and twelve submarines.[20] Even the lower establishment proved too expensive and in 1940 the Red Sea Flotilla had seven older fleet destroyers, the 5th Destroyer Division with the Leone-class destroyers Pantera, Tigre and Leone and the 3rd Destroyer Division with the Sauro-class torpedo boats (a class of ships between the size of small, fast motor torpedo boats and destroyers, not found in the Royal Navy) Francesco Nullo, Nazario Sauro, Cesare Battisti and Daniele Manin. There were Orsini and Acerbi two old local defence torpedo boats and a squadron of five first world war Motoscafo Armato Silurante (MAS, motor torpedo boats).[21]

The Flotilla had eight modern submarines (Archimede, Galileo Ferraris, Galileo Galilei, Torricelli, Galvani, Guglielmotti, Macallé and Perla). The flotilla was based at Massawa in Eritrea on the Red Sea. The port linked Axis-occupied Europe and the naval facilities in the Italian concession zone at Tientsin in China.[21] There were limited port facilities at Assab, in Eritrea and at Mogadishu in Italian Somaliland. When the Mediterranean route was closed to Allied merchant ships in April 1940, the Italian naval bases in East Africa were well placed for attacks on convoys en route to Suez up the east coast of Africa and through the Red Sea. The finite resources in Italian East Africa were intended to last for a war of about six months' duration, the submarines denying the Red Sea route to the British.[22]

Mediterranean and Middle East

The British had based forces in Egypt since 1882 but these were greatly reduced by the terms of the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936. A small British and Commonwealth force garrisoned the Suez Canal and the Red Sea route, which was vital to British communications with its Indian Ocean and Far Eastern territories. In mid-1939, General Archibald Wavell was appointed General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) of the new Middle East Command, over the Mediterranean and Middle East theatres. Wavell was responsible for the defence of Egypt through the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, British Troops Egypt, to train the Egyptian Army and co-ordinate military operations with the Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean, Admiral Andrew Cunningham, the Commander-in-Chief, East Indies, Vice-Admiral Ralph Leatham, the Commander-in-Chief India, General Robert Cassels, the Inspector General, African Colonial Forces, Major-General Douglas Dickinson and the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief Middle East, Air Chief Marshal William Mitchell.[23][c] (French divisions in Tunisia faced the Italian 5th Army on the western Libyan border, until the Franco-Axis Armistice of 22 June 1940.) In Libya, the Regio Esercito Italiana (Royal Italian Army) had about 215,000 men and in Egypt, the British had about 36,000 troops, with another 27,500 men training in Palestine.[25] Wavell had about 86,000 troops at his disposal for Libya, Iraq, Syria, Iran and East Africa.[26]

Middle East Command

Middle East Command was established before the war to control land operations and co-ordinate with the naval and air commands in the Mediterranean and Middle East. Wavell was allowed only five staff officers for plans and command of an area of 3,500,000 sq mi (9,100,000 km2).[27] From 1940 to 1941, operations took place in the Western Desert of Egypt, East Africa, Greece and the Middle East. In July 1939, Wavell devised a strategy to defend and then to dominate the Mediterranean as a base to attack Germany through eastern and south-eastern Europe. The conquest of Italian East Africa came second only to the defence of Egypt and the Suez Canal. In August, Wavell ordered for plans to be made quickly to gain control of the Red Sea. He specified a concept of offensive operations from Djibouti to Harar and then Addis Ababa or Kassala to Asmara then Massawa, preferably on both lines simultaneously. Wavell reconnoitred East Africa in January 1940 and the theatre was formally added to his responsibilities. He expected that the Somalilands could be defended with minor reinforcement. If Italy joined the war, Ethiopia would be invaded as soon as there were sufficient troops. Wavell also co-ordinated plans with South Africa in March. On 1 May 1940, Wavell ordered British Troops Egypt to mobilise discreetly for military operations in western Egypt but after the June debacle in France, Wavell had to follow a defensive strategy.[28]

After Italian operations in Sudan at Kassala and Gallabat in June, Winston Churchill blamed Wavell for a "static policy". Anthony Eden, the Secretary of State for War, communicated to Wavell that an Italian advance towards Khartoum should be destroyed. Wavell replied that the Italian attacks were not serious but went to Sudan and Kenya to see for himself and met Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie at Khartoum.[29] Eden convened a conference in Khartoum at the end of October 1940 with Selassie, South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts (an advisor to Churchill), Wavell, Lieutenant-General William Platt and Lieutenant-General Alan Cunningham. A plan to attack Ethiopia, including support for Ethiopian irregular forces, was agreed.[26] In November 1940, the British gained an intelligence advantage when the Government Code and Cypher School (GC & CS) at Bletchley Park broke the high grade cypher of the Italian Army in East Africa. Later that month, the replacement cypher for the Regia Aeronautica was broken by the Combined Bureau, Middle East (CBME).[30]

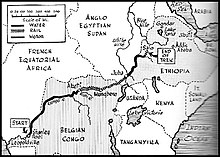

In September 1940, Wavell ordered the commanders in Sudan and Kenya to make limited attacks once the rainy season had ended. On the northern front, Platt was to attack Gallabat and the vicinity; on the southern front, Cunningham was to advance northwards from Kenya through Italian Somaliland into Ethiopia. In early November 1940, Cunningham had taken over the East African Force from Dickinson, who was in poor health. While Platt advanced from the north and Cunningham from the south, Wavell planned for a third force to be landed in British Somaliland by amphibious assault to re-take the colony, prior to advancing into Ethiopia. The three forces were to rendezvous at Addis Ababa. The conquest of the AOI would remove the land threat to supplies and reinforcements coming from Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa and British East Africa via the Suez Canal for the Western Desert campaign and re-open the land route from Cape Town to Cairo.[31]

East Africa Force

On 10 June 1940, East Africa Force (Major-General Douglas Dickinson) was established for North-East Africa, East Africa and British Central Africa. In Sudan about 8,500 troops and 80 aircraft guarded a 1,200 mi (1,900 km) frontier with the AOI.[32] Platt had 21 companies (4,500 men) of the Sudan Defence Force (SDF) of which five (later six) were organised as motor machine-gun companies. There was no artillery, but the Sudan Horse was converting to a 3.7-inch mountain howitzer battery. The 1st Battalion Worcestershire Regiment, 1st Battalion Essex Regiment and the 2nd Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment, were, in mid-September, incorporated into the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade, 10th Indian Infantry Brigade and 9th Indian Infantry Brigade respectively of the 5th Indian Infantry Division (Major-General Lewis Heath) when it arrived.[33]

The 4th Indian Infantry Division (Major-General Noel Beresford-Peirse) was transferred from Egypt in December.[34] The British had an assortment of armoured cars and B Squadron 4th Royal Tank Regiment (4th RTR) with Matilda infantry tanks joined the 4th Indian Division in January 1941.[35] On the outbreak of hostilities, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Reginald Chater in British Somaliland had about 1,754 troops comprising the Somaliland Camel Corps (SCC) and a battalion of the 1st Battalion Northern Rhodesia Regiment. By August, the 1/2nd Punjab and 3/5th Punjab regiments had been transferred from Aden and the 2nd Battalion of the King's African Rifles (KAR) with the 1st East African Light Battery (3.7-inch howitzers) came from Kenya, raising the total to 4,000 troops, in the first week of August. In the Aden Protectorate, British Forces Aden (Air Vice-Marshal George Reid) had a garrison of the two Indian infantry battalions until they were transferred to British Somaliland in August.[36]

Ethiopia

In August 1939, Wavell had ordered a covert plan to encourage the rebellion in the western Ethiopian province of Gojjam, which the Italians had never been able to repress. In September, Colonel Daniel Sandford arrived to run the project, but until the Italian declaration of war, the conspiracy was held back by the government's policy of appeasement.[37][d] Mission 101 was formed to co-ordinate the activities of the Ethiopian resistance. In June 1940, Selassie arrived in Egypt and in July, went to Sudan to meet Platt and discuss plans to recapture Ethiopia, despite Platt's reservations.[37] In July, the British recognised Selassie as emperor and in August, Mission 101 entered Gojjam province to reconnoitre. Sandford requested that supply routes be established before the rains ended, to the area north of Lake Tana and that Selassie should return in October, as a catalyst for the uprising. Gaining control of Gojjam required the Italian garrisons to be isolated along the main road from Bahir Dar Giorgis south of Lake Tana, to Dangila, Debre Markos and Addis Ababa to prevent them concentrating against the Arbegnoch (Amharic for Patriots).[39]

Italian reinforcements arrived in October and patrolled more frequently, just as dissensions among local potentates were reconciled by Sandford's diplomacy.[39] The Frontier Battalion of the Sudan Defence Force, set up in May 1940, was joined at Khartoum by the 2nd Ethiopian and 4th Eritrean battalions, which were raised from émigré volunteers in Kenya. Operational Centres consisting of an officer, five NCOs and several picked Ethiopians were formed and trained in guerrilla warfare to provide leadership cadres and £1 million was set aside to finance operations. Major Orde Wingate was sent to Khartoum with an assistant to join the headquarters of the SDF. On 20 November, Wingate was flown to Sakhala to meet Sandford, and the RAF managed to bomb Dangila, drop propaganda leaflets and supply Mission 101, which raised Ethiopian morale, which had suffered much from Italian air power since the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. Mission 101 managed to persuade the Arbegnoch north of Lake Tana to spring several ambushes on the Metemma–Gondar road, and the Italian garrison at Wolkait was withdrawn in February 1941.[40]

Northern front, 1940

British Somaliland 1940

On 3 August 1940, the Italians invaded with two colonial brigades, four cavalry squadrons, 24 M11/39 medium tanks and L3/35 tankettes, several armoured cars, 21 howitzer batteries, pack artillery and air support.[41] The British had a garrison of two companies of the Sudan Defence Force, two motor machine-gun companies and a mounted infantry company. Kassala was bombed and then attacked, the British retiring slowly.[42] On 4 August, the Italians advanced with a western column towards Zeila, a central column (Lieutenant-General Carlo De Simone) towards Hargeisa and an eastern column towards Odweina in the south. The SCC skirmished with the advancing Italians as the main British force slowly retired. On 5 August, the towns of Zeila and Hargeisa were captured, cutting off the British from French Somaliland. Odweina fell the following day and the Italian central and eastern columns joined. On 11 August, Major-General Alfred Reade Godwin-Austen was diverted to Berbera, en route to Kenya to take command as reinforcements increased the British garrison to five battalions.[43] (From 5 to 19 August, RAF squadrons based at Aden flew 184 sorties, dropped 60 long tons (61 t) of bombs, lost seven aircraft destroyed and ten damaged.)[44]

Battle of Tug Argan

On 11 August, the Italians began the Battle of Tug Argan (tug, a dry, sandy riverbed), where the road from Hargeisa crosses the Assa hills and by 14 August, the British were at risk of defeat in detail by the larger Italian force and its greater quantity of artillery. Close to being cut off and with only one battalion left in reserve, Godwin-Austen contacted Henry Maitland Wilson, commander of the British Troops in Egypt in Cairo (Wavell was in London) and received permission to withdraw from the colony. The 2nd Battalion, Black Watch, supported by two companies of the 2nd King's African Rifles and parties of the 1st/2nd Punjab Regiment covered the retreat of the British contingent to Berbera.[45]

By 2:00 p.m. on 18 August, most of the contingent had been evacuated to Aden but HMAS Hobart and the HQ stayed behind until morning before sailing and the Italians entered Berbera on the evening of 19 August.[45] In the final four days, the RAF flew twelve reconnaissance and 19 reconnaissance-bombing sorties, with 72 attacks on Italian transport and troop columns; 36 fighter sorties were flown over Berbera.[44] The British suffered casualties of 38 killed and 222 wounded; the Italians suffered 2,052 casualties; fuel and ammunition expenditure and wear and tear on vehicles was difficult to remedy, which forced the Italians to return to the defensive.[46] Churchill criticised Wavell for abandoning the colony without enough fighting but Wavell called it a textbook withdrawal in the face of superior numbers.[47]

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan shared a 1,000 mi (1,600 km) border with the AOI and on 4 July 1940, was invaded by an Italian force of about 6,500 men from Eritrea, which advanced on a railway junction at Kassala. The Italians forced the British garrison of 320 men of the SDF and some local police to retire after inflicting casualties of 43 killed and 114 wounded for ten casualties of their own.[48][49] The Italians also drove a platoon of No 3 Company, Eastern Arab Corps (EAC) of the SDF, from the small fort at Gallabat, just over the border from Metemma, about 200 mi (320 km) south of Kassala and took the villages of Qaysān, Kurmuk and Dumbode on the Blue Nile. From there the Italians ventured no further into Sudan owing to a lack of fuel and fortified Kassala with anti-tank defences, machine-gun posts and strongpoints, later establishing a brigade-strong garrison. The Italians were disappointed to find little anti-British sentiment among the Sudanese population.[50]

The 5th Indian Division began to arrive in Sudan in early September 1940. The 29th Indian Infantry Brigade were placed on the Red Sea coast to protect Port Sudan, the 9th Indian Infantry Brigade was based south-west of Kassala and the 10th Indian Infantry Brigade (William Slim) were sent to Gedaref, with the divisional headquarters, to block an Italian attack on Khartoum from Goz Regeb to Gallabat, on a front of 200 mi (320 km). Gazelle Force (Colonel Frank Messervy) was formed on 16 October, as a mobile unit to raid Italian territory and delay an Italian advance.[51][e]

Gallabat fort lay in Sudan and Metemma a short way across the Ethiopian border, beyond the Boundary Khor, a dry riverbed with steep banks covered by long grass. Both places were surrounded by field fortifications and Gallabat was held by a colonial infantry battalion. Metemma had two colonial battalions and a banda formation, all under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Castagnola. The 10th Indian Infantry Brigade, a field artillery regiment and B Squadron, 6th RTR with seven Cruiser Mk I (A9) tanks and seven Light Tank Mk VI, attacked Gallabat on 6 November at 5:30 a.m.[53] An RAF contingent of six Wellesley bombers and nine Gloster Gladiator fighters, were thought sufficient to overcome the 17 Italian fighters and 32 bombers believed to be in range.[54] The infantry assembled 1–2 mi (1.6–3.2 km) from Gallabat, whose garrison was unaware that an attack was coming, until the RAF bombed the fort and put the wireless out of action. The field artillery began a simultaneous bombardment; after an hour the gunners changed targets and bombarded Metemma. The previous night, the 4th Battalion 10th Baluch Regiment occupied a hill overlooking the fort as a flank guard. The troops on the hill covered the advance at 6:40 a.m. of the 3rd Royal Garwhal Rifles followed by the tanks. The Indians reached Gallabat and fought hand-to-hand with the 65th Infantry Division "Granatieri di Savoia" and some Eritrean troops in the fort. At 8:00 a.m. the 25th and 77th Colonial battalions counter-attacked and were repulsed but three British tanks were knocked out by mines and six by mechanical failure caused by the rocky ground.[55]

The defenders at Boundary Khor were dug in behind fields of barbed wire and Castagnola had contacted Gondar for air support. Italian bombers and fighters attacked all day, shot down seven Gladiators for a loss of five Fiat CR-42s and destroyed the lorry carrying spare parts for the tanks. The ground was so hard and rocky that there were no trenches and when Italian bombers made their biggest attack, the infantry had no cover. An ammunition lorry was set on fire by burning grass and the sound was taken to be an Italian counter-attack from behind. When a platoon advanced towards the sound with fixed bayonets, some troops thought that they were retreating.[56] Part of the 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment at the fort broke and ran, taking some of the Gahrwalis with them. Many of the British fugitives mounted their transport and drove off, spreading the panic and some of the runaways reached Doka before being stopped.[55][f]

The Italian bombers returned next morning and Slim ordered a withdrawal from Gallabat Ridge 3 mi (4.8 km) west to less exposed ground that evening. Sappers from the 21st Field Company remained behind to demolish the remaining buildings and stores in the fort. The artillery bombarded Gallabat and Metemma and set off Italian ammunition dumps full of pyrotechnics. British casualties since 6 November were 42 men killed and 125 wounded.[57] The brigade patrolled to deny the fort to the Italians and on 9 November, two Baluch companies attacked and held the fort during the day and retired in the evening. During the night an Italian counter-attack was repulsed by artillery-fire and next morning the British re-occupied the fort unopposed. Ambushes were laid and prevented Italian reinforcements from occupying the fort or the hills on the flanks, despite frequent bombing by the Regia Aeronautica.[56]

Southern front, 1940

British East Africa (Kenya)

On the Italian declaration of war on 10 June 1940, East Africa Force (Lieutenant-General Douglas Dickinson) comprised two East African brigades of the King's African Rifles organised as a Northern Brigade and a Southern Brigade with a reconnaissance regiment, a light artillery battery and the 22nd Mountain Battery Royal Indian Artillery (RIA). By March 1940, the KAR strength had reached 883 officers, 1,374 non-commissioned officers and 20,026 African other ranks.[58][g] Wavell ordered Dickinson to defend Kenya and to pin down as many Italian troops as possible. Dickinson planned to defend Mombasa with the 1st East African Infantry Brigade and to deny a crossing of the Tana River and the fresh water at Wajir with the 2nd East African Infantry Brigade.[59]

Detachments were to be placed at Marsabit, Moyale and at Turkana near Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana), an arc 850 mi (1,370 km) long. The Italians were thought to have troops at Kismayo, Mogadishu, Dolo, Moyale and Yavello, which turned out to be colonial troops and bande, with two brigades at Jimma, ready to reinforce Moyale or attack Lake Rudolf and then invade Uganda.[59] By the end of July, the 3rd East African Infantry Brigade and the 6th East African Infantry Brigade had been formed. A Coastal Division and a Northern Frontier District Division had been planned but then the 11th (African) Division and the 12th (African) Division were created instead.[58]

On 1 June, the first South African unit arrived at the port of Mombasa in Kenya and by the end of July, the 1st South African Infantry Brigade Group had arrived. On 13 August, the 1st South African Division was formed and by the end of 1940, about 27,000 South Africans were in East Africa, in the 1st South African Division, the 11th (African) Division and the 12th (African) Division. Each South African brigade group consisted of three rifle battalions, an armoured car company and signal, engineer and medical units.[60] By July, under the terms of a war contingency plan, the 2nd (West Africa) Infantry Brigade, from the Gold Coast (Ghana) and the 1st (West Africa) Infantry Brigade from Nigeria, were provided for service in Kenya by the Royal West African Frontier Force (RWAFF). The 1st (West African) Brigade, the two KAR brigades and some South African units, formed the 11th (African) Division. The 12th (African) Division had a similar formation with the 2nd (West African) Brigade.[58]

At dawn on 17 June, the Rhodesians supported a raid by the SDF on the Italian desert outpost of El Wak in Italian Somaliland about 90 mi (140 km) north-east of Wajir. The Rhodesians bombed and burnt down thatched mud huts and generally harassed Italian troops. Since the main fighting at that time was against Italian advances towards Moyale in Kenya, the Rhodesians concentrated there. On 1 July, an Italian attack on the border town of Moyale, on the edge of the Ethiopian escarpment, where the tracks towards Wajir and Marsabit meet, was repulsed by a company of the 1st KAR and reinforcements were moved up. The Italians carried out a larger attack by about four battalions on 10 July, after a considerable artillery bombardment and after three days the British withdrew unopposed. The Italians eventually advanced to water holes at Dabel and Buna, nearly 62 mi (100 km) inside Kenya but lack of supplies prevented a further advance.[61][62]

Italian strategy, December 1940

After the conquest of British Somaliland the Italians adopted a more defensive posture. In late 1940, Italian forces suffered defeats in the Mediterranean Campaign, the Operation Compass in the Western Desert, the Battle of Britain and in the Greco-Italian War. This prompted General Ugo Cavallero, the new Italian Chief of the Chief of the General Staff in Rome, to adopt a new strategy in East Africa. In December 1940, Cavallero thought that Italian forces in East Africa should abandon offensive actions against the Sudan and the Suez Canal and concentrate on the defence of the AOI.[63] After Cavallero and Aosta requested permission to withdraw from the Sudanese frontier, the army high command in Rome ordered Italian forces in East Africa to withdraw to better defensive positions.[64]

Frusci was ordered to withdraw from Kassala and Metemma in the lowlands along the Eritrea–Sudan border and hold the mountain passes on the Kassala–Agordat and Metemma–Gondar roads. Frusci chose not to withdraw from the lowlands, because withdrawal would involve too great a loss of prestige and because Kassala was an important railway junction; holding it prevented the British from using the railway to carry supplies from Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast to their base at Gedaref.[63] Information on the Italian withdrawal plan was quickly decrypted by the British and Platt was able to begin his offensive into Eritrea on 18 January 1941, three weeks ahead of schedule.[30]

War in the air

In Sudan, the Royal Air Force (RAF) Air Headquarters Sudan (Headquarters 203 Group from 17 August, Air Headquarters East Africa from 19 October), subordinate to the AOC-in-C Middle East, had 14 Squadron, 47 Squadron and 223 Squadron (Wellesley bombers).[65] A flight of Vincent biplanes from 47 Squadron performed Army Co-operation duties and were later reinforced from Egypt by 45 squadron (Blenheims). Six Gladiator biplane fighters were based in Port Sudan for trade protection and anti-submarine patrols over the Red Sea, the air defence of Port Sudan, Atbara and Khartoum and for army support.[66]

In May, 1 (Fighter) Squadron South African Air Force (SAAF) arrived, was transferred to Egypt to convert to Gladiators and returned to Khartoum in August.[66] The SAAF in Kenya comprised 12 Squadron (Junkers Ju 86 bombers), 11 Squadron (Battle bombers), 40 Squadron (Hart light bombers), 2 Squadron (Fury fighters) and 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron RAF (Hardy general-purpose aircraft). Better aircraft became available later but the first aircraft were old and slow, the South Africans even pressing an old Valentia biplane into service as a bomber.[67]

The South Africans faced experienced Italian pilots, including a cadre of Spanish Civil War veterans. Despite its lack of experience, 1 Squadron claimed 48 enemy aircraft destroyed and 57 damaged in the skies over East Africa. A further 57 were claimed destroyed on the ground. all for the loss of six pilots. It is thought the unit was guilty of severe over-claiming.[68] From November 1940 to early January 1941, Platt put pressure on the Italians along the Ethiopia–Sudan border with patrols and raids by ground troops and aircraft. Hurricanes and more Gladiators began to replace some of the older models. On 6 December, a large concentration of Italian motor transport was bombed and strafed by Commonwealth aircraft a few miles north of Kassala.[69]

The same aircraft then proceeded to machine-gun from low level the nearby positions of the Italian Blackshirts and colonial infantry. A few days later, the aircraft bombed the Italian base at Keru, fifty miles east of Kassala. The Commonwealth pilots had the satisfaction of seeing supply dumps, stores and transport enveloped in flame and smoke as they flew away. One morning in mid-December, a force of Italian fighters strafed a Rhodesian landing-strip at Wajir near Kassala, where two Hardys were caught on the ground and destroyed; 5,000 US gal (19,000 L; 4,200 imp gal) of fuel were set alight and four Africans were killed and eleven injured fighting the fire.[69][70]

War at sea, 1940

The approaches to the Red Sea through the Gulf of Aden and the Bab-el-Mandeb (Gate of Tears Strait) is 15 nmi (28 km; 17 mi) wide. With the Italian declaration of war on 10 June and the loss of French naval support in the Mediterranean after the Armistice of 22 June, the 1,200 nmi (2,200 km; 1,400 mi)-long Red Sea passage to Suez became the main British sea route to the Middle East. South of Suez the British-held Port Sudan, about halfway down on the Sudan coast and the base at Aden, 100 nmi (190 km; 120 mi) east of Bab-el-Mandeb on the Arabian Peninsula. The principal Italian naval force (Contrammiraglio [Rear-Admiral] Mario Bonetti) was based at Massawa in Eritrea, about 350 nmi (650 km; 400 mi) north of the Bab-el-Mandeb, well placed for the Red Sea Flotilla to attack Allied convoys.[71]

British code-breakers of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park in England, deciphered Italian orders of 19 May, coded using C38m machines, secretly to mobilise the army and air force in East Africa. Merchant traffic was stopped by the British on 24 May, pending the introduction of a convoy system. The Red Sea Force (Senior Naval Officer Red Sea, Rear-Admiral Arthur Murray), operational at Aden since April with the light cruisers HMS Liverpool and HMAS Hobart (Liverpool was replaced by HMS Leander), was reinforced by the anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Carlisle, which sailed south with Convoy BS 4, the 28th Destroyer Flotilla comprising HMS Khartoum, Kimberley, Kingston and Kandahar and three sloops from the Mediterranean. The force was to conduct a blockade Italian East Africa (Operation Begum), attack the Red Sea Flotilla and protect the sea route from Aden to Suez.[71]

On 6 June, the Azio-class minelayer Ostia used 470 mines to lay eight barrages off Massawa and the destroyer Pantera dropped 110 mines in two barrages off Assab the day after. When Italy declared war on 10 June, Galileo Ferraris sailed for French Somaliland (Djibouti), Galileo Galilei to Aden, Galvani to the Gulf of Oman and Mecallé to Port Sudan.[72] On 14 June Torricelli put to sea to relieve Galileo Ferraris whose crew had been incapacitated by chloromethane poisoning from the refrigeration system.[73][h] The crew of Macallé was also afflicted; the boat was run aground and lost on 15 June.[74] On 18 June, Galileo Galilei boarded and released the neutral Yugoslav steamship Dravo and the next day engaged the armed trawler HMS Moonstone off Aden. All but one officer was killed by shell-fire and Galileo Galilei was captured along with many documents including operational orders for four other Italian submarines.[75][i]

Archimede, Perla and Guglielmotti sailed from 19 to 21 June. On 26 June, Guglielmotti ran onto a shoal and suffered severe damage; the wreck was salvaged later.[72] Documents recovered from Galileo Galilei were used to intercept and damage Torricelli on 21 June. The submarine headed for home but was caught off Perim Island and sunk by Kandahar, Kingston, Khartoum and the sloop Shoreham. Several hours afterwards, a torpedo on Khartoum, damaged by a shell from Torricelli, exploded and caused an uncontrollable fire. Khartoum tried to reach Perim Harbour about 7 nmi (13 km; 8.1 mi) distant but the crew and prisoners had to abandon ship; later a magazine explosion wrecked the vessel. The sloop Falmouth exploited the document find from Galileo Galilei to sink Galvani in the Gulf of Oman on 24 June.[77] On 13 August, Galileo Ferraris made an abortive attempt to intercept the battleship HMS Royal Sovereign en route from Suez to Aden.[78]

From 13 to 19 August Kimberley and the sloop HMS Auckland bombarded Italian troops advancing west of Berbera in British Somaliland. Italian air raids on Berbera caused splinter damage to Hobart as it participated in the evacuation of Berbera with Carlisle, Caledon Ceres, Kandahar, Kimberley and the sloops Shoreham, HMAS Parramatta, Auckland, auxiliary cruisers Chakdina, Chantala and Laomédon, the transport HMIS Akbar and the hospital ship HMHS Vita, lifting 5,960 troops, 1,266 civilians and 184 sick and wounded. On 18 November the cruiser HMS Dorsetshire bombarded Zante in Italian Somaliland[79] British naval forces supported land operations and blockaded the remnants the Red Sea Flotilla at Massawa. By the end of 1940, the British had gained control of East African coastal routes and the Red Sea; Italian forces in the AOI declined as fuel, spare parts and supplies from Italy ran out. There were six Italian air attacks on convoys in October and none after 4 November.[80]

Red Sea convoys

During 16 June 1940, Galileo Galilei sank the Norwegian tanker James Stove (8,215 gross register tons [GRT]), sailing independently about 12 nmi (22 km; 14 mi) south of Aden. On 2 July the first of the BN convoys (Bombay Northward; Bombay to Suez, then Aden to Suez 1940–1941), comprising six tankers and three freighters, assembled in the Gulf of Aden.[76] Italian sorties against the BN–BS convoys (Bombay Southward; Suez to Aden, late 1940 to early 1941) were dispiriting failures; from 26 to 31 July, Guglielmotti failed to find two Greek merchantmen and a sortie by the torpedo boats Cesare Battisti and Francesco Nullo was also abortive. Guglielmotti from 21 to 25 August, Galileo Ferraris (25–31 August), Francesco Nullo and Nazario Sauro from 24 to 25 August and the destroyers Pantera and Tigre (28–29 August) failed to find Greek ships in the Red Sea, despite agent reports and sightings by air reconnaissance.[81] Italian aircraft and submarines had little more success.[82]

On the night of 5/6 September, Cesare Battisti, Daniele Manin and Nazario Sauro sailed, followed on 6/7 September by the destroyers Leone and Tigre to attack a northbound convoy (BN 4) found by air reconnaissance but found nothing. Further to the north, Galileo Ferraris and Guglielmotti also failed to find BN 4 but Guglielmotti torpedoed the Greek tanker Atlas (4,008 GRT) south of the Farasan Islands straggling behind the convoy. Leone, Pantera, Cesare Battisti and Daniele Manin with the submarines Archimede and Gugliemotti failed to find a convoy of 23 ships spotted by air reconnaissance. Bhima (5,280 GRT) in convoy BN 5 was damaged by bombs and one man killed; the ship was towed to Aden and beached.[83] In August the British ran four convoys in each direction, five in September and seven in October, 86 ships in BN convoys and 72 in BS (southbound) convoys; the Regia Aeronautica managed only six air attacks in October and none after 4 November.[84]

The Attack on Convoy BN 7, took place from 20 to 21 October and was the only destroyer attack on a convoy, despite gaining precise information on BN convoys as they passed French Somaliland.[84] The 31 ships of BN 7 were escorted by the cruiser Leander, the destroyer HMS Kimberley, the sloops Auckland, HMAS Yarra and HMIS Indus with the minesweepers Derby and Huntley, with air cover from Aden.[85] Guglielmo Marconi and Galileo Ferraris, stationed to the north, failed to intercept the convoy but on 21 October the destroyers Nazario Sauro and Francesco Nullo with the destroyers Pantera, Leone attacked the convoy 150 nmi (280 km; 170 mi) east of Massawa; the attackers caused only superficial damage to one ship.[86]

Kimberley forced Francesco Nullo aground on an island near Massawa, at the Action off Harmil Island on the morning of 21 October. Kimberley was hit in the engine room by a shore battery and had to be towed to Port Sudan by Leander. The wreck of Francesco Nullo was bombed on 21 October by three Blenheims of 45 Squadron.[86] From 22 to 28 November, Archimede and Galileo Ferraris sailed to investigate reports of a convoy but found nothing, as did Tigre, Leone, Daniele Manin, Nazario Sauro and Galileo Ferraris from 3 to 5 December. From 12 to 22 December Archimede sailed twice after ship sightings but both sorties came to nothing; Galileo Ferraris sortied off Port Sudan.[87] from June to December the RAF had escorted 54 BN and BS convoys from which one ship was sunk and one damaged by Italian aircraft.[88]

French Somaliland 1940–1942

The governor of French Somaliland (now Djibouti), Brigadier-General Paul Legentilhomme had a garrison of seven battalions of Senegalese and Somali infantry, three batteries of field guns, four batteries of anti-aircraft guns, a company of light tanks, four companies of militia and irregulars, two platoons of the camel corps and an assortment of aircraft. After visiting from 8 to 13 January 1940, Wavell decided that Legentilhomme would command the military forces in both Somalilands should war with Italy come.[89] In June, an Italian force was assembled to capture the port city of Djibouti, the main military base.[90]

After the fall of France in June, the neutralisation of Vichy French colonies allowed the Italians to concentrate on the more lightly defended British Somaliland.[91] On 23 July, Legentilhomme was ousted by the pro-Vichy naval officer Pierre Nouailhetas and left on 5 August for Aden, to join the Free French. In March 1941, the British enforcement of a strict contraband regime to prevent supplies being passed on to the Italians, lost its point after the conquest of the AOI. The British changed policy, with encouragement from the Free French, to "rally French Somaliland to the Allied cause without bloodshed". The Free French were to arrange a voluntary ralliement by propaganda (Operation Marie) and the British were to blockade the colony.[92] Wavell considered that if British pressure was applied, a rally would appear to have been coerced. Wavell preferred to let the propaganda continue and provided a small amount of supplies under strict control.[93]

When the policy had no effect, Wavell suggested negotiating with the Vichy governor Louis Nouailhetas, to use the port and railway. The suggestion was accepted by the British government but because of the concessions granted to the Vichy regime in Syria, proposals were made to invade the colony instead. In June, Nouailhetas was given an ultimatum, the blockade was tightened and the Italian garrison at Assab was defeated by an operation from Aden. For six months, Nouailhetas remained willing to grant concessions over the port and railway but would not tolerate Free French interference. In October the blockade was reviewed but the beginning of the war with Japan in December, led to all but two blockade ships being withdrawn. On 2 January 1942, the Vichy government offered the use of the port and railway, subject to the lifting of the blockade but the British refused and ended the blockade unilaterally in March.[93]

Northern front, 1941

Operation Camilla

Operation Camilla was a deception concocted by Lieutenant-Colonel Dudley Clarke to deceive the Italians, making them believe that the British planned to re-conquer British Somaliland with the 4th and 5th Indian divisions, transferred from Egypt to Gedaref and Port Sudan. In December 1940, Clarke constructed a model operation for Italian military intelligence to discover and set up administration offices at Aden. Clarke arranged for the Italian defences around Berbera to be softened up by air and sea raids from Aden and distributed maps and pamphlets on the climate, geography and population of British Somaliland.[94]

"Sibs" (sibilare, hisses or whistles), were circulated among civilians in Egypt. Bogus information was planted on the Japanese consul at Port Said and indiscreet wireless messages were transmitted. The operation began on 19 December 1940 to mature early in January 1941. The deception was a success but the plot backfired when the Italians began to evacuate British Somaliland instead of sending reinforcements. Troops were sent north into Eritrea, where the real attack was coming, instead of to the east. Part of the deception, with misleading wireless transmissions, did convince the Italians that two Australian divisions were in Kenya, which led the Italians to reinforce the wrong area.[94]

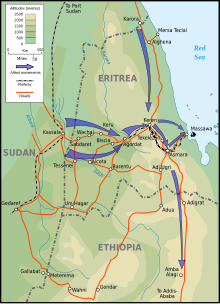

Eritrea

In November 1940, Gazelle Force operated from the Gash river delta against Italian advanced posts around Kassala on the Ethiopian plateau, where hill ranges from 2,000–3,000 ft (610–910 m) bound wide valleys and the rainfall makes the area malarial from July to October.[95] On 11 December, Wavell ordered the 4th Indian Division to withdraw from Operation Compass in the Western Desert and move to Sudan. The transfer took until early January 1941 and Platt intended to begin the offensive on the northern front on 8 February, with a pincer attack on Kassala, by the 4th and 5th Indian divisions, less a brigade each.[96]

News of the Italian disaster in Egypt, the harassment by Gazelle Force and the activities of Mission 101 in Ethiopia, led to the Italians withdrawing their northern flank to Keru and Wachai and then on 18 January to retreat hurriedly from Kassala and Tessenei, the triangle of Keru, Biscia and Aicota. Wavell had ordered Platt to advance the offensive from March to 9 February and then to 19 January, when it seemed that Italian morale was crumbling.[97][j] The withdrawal led Wavell to order a pursuit and the troops arriving at Port Sudan (Briggs Force) to attack at Karora and advance parallel to the coast, to meet the forces coming from the west.[99]

Battle of Agordat, Barentu

Two roads joined at Agordat and went through to Keren, the only route to Asmara. The 4th Indian Division was sent 40 mi (64 km) along the road to Sabderat and Wachai, thence as far towards Keru as supplies allowed, with the Matilda Infantry tanks of B Squadron, 4th RTR to join from Egypt. The 5th Indian Division was to capture Aicota, ready to move east to Barentu or north-east to Biscia. Apart from air attacks the pursuit was not opposed until Keru Gorge, held by a rearguard of the 41st Colonial Brigade. The brigade retreated on the night of 22/23 January, leaving General Ugo Fongoli, his staff and 800 men behind as prisoners.[100] On 28 January, the 3/14th Punjab Regiment made a flanking move to Mt Cochen to the south and on 30 January, five Italian colonial battalions counter-attacked with mountain artillery support, forcing back the Indians.[100]

On the morning of 31 January the Indians attacked again and advanced towards the main road. The 5th Indian Brigade on the plain attacked with the Matildas, overran the Italians, knocked out several Italian tanks and cut the road to Keren. The 2nd Colonial Division retreated having lost 1,500 to 2,000 infantry, 28 field guns and several medium and light tanks. Barentu, held by nine battalions of the 2nd Colonial Division (about 8,000 men), 32 guns and about thirty-six dug in M11/39 tanks and armoured cars was attacked by 10th Indian Infantry Brigade from the north against a determined Italian defence, as the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade advanced from the west, slowed by demolitions and rearguards. On the night of 31 January/1 February, the Italians retreated along a track towards Tole and Arresa and on 8 February, abandoned vehicles were found by the pursuers. The Italians had taken to the hills, leaving the Tessenei–Agordat road open.[100]

Battle of Keren

On 12 January, Aosta had sent a regiment of the 65th Infantry Division "Granatieri di Savoia" (General Amedeo Liberati) and three colonial brigades to Keren.[101] The 4th and 5th Indian Infantry Divisions advanced eastwards from Agordat into the rolling countryside, which gradually increased in elevation towards the Keren Plateau, through the Ascidira Valley. There was an escarpment on the left and a spur rising to 6,000 ft (1,800 m) on the right of the road and the Italians were dug in on heights which dominated the massifs, ravines and mountains. The defensive positions had been surveyed before the war and chosen as the main defensive position to guard Asmara and the Eritrean highlands from an invasion from Sudan. On 15 March, after several days of bombing, the 4th Indian Division attacked on the north and west side of the road to capture ground on the left flank, ready for the 5th Indian Division to attack on the east side.[102]

The Indians met a determined defence and made limited progress but during the night the 5th Indian Division captured Fort Dologorodoc, 1,475 ft (450 m) above the valley. The "Granatieri di Savoia" and "Alpini" counter-attacked Dologorodoc seven times from 18 to 22 March but the attacks were costly failures. Wavell flew to Keren to assess the situation and on 15 March, watched with Platt as the Indians made a frontal attack up the road, ignoring the high ground on either side and breaking through. Early on 27 March, Keren was captured after a battle lasting 53 days, for a British and Commonwealth loss of 536 men killed and 3,229 wounded; Italian losses were 3,000 Italian and 9,000 Ascari killed and about 21,000 wounded.[102] The Italians conducted a fighting withdrawal under air attack to Ad Teclesan, in a narrow valley on the Keren–Asmara road, the last defensible position before Asmara. The defeat at Keren had shattered the morale of the Italian forces and when the British attacked early on 31 March, the position fell and 460 Italian prisoners and 67 guns were taken; Asmara was declared an open town the next day and the British entered unopposed.[103]

Massawa

Admiral Mario Bonetti, the commander of the Italian Red Sea Flotilla and the garrison at Massawa, had 10,000 troops and about 100 tanks to defend the port.[104] During the evening of 31 March, three of the last six destroyers at Massawa put to sea to raid the Gulf of Suez and then scuttle themselves. Leone ran aground and sank the next morning; the sortie was postponed and on 2 April the last five destroyers left to attack Port Sudan and then sink themselves.[105] Heath telephoned Bonetti with an ultimatum to surrender and not block the harbour by scuttling ships. If this was refused, the British would leave Italian citizens in Eritrea and Ethiopia to fend for themselves. The 7th Indian Infantry Brigade Group sent small forces towards Adowa and Adigrat and the rest advanced down the Massawa road, which declined by 7,000 ft (2,100 m) in 50 mi (80 km). The Indians rendezvoused at Massawa with Briggs Force by 5 April, after it had cut across country.[103]

Bonetti was once again called upon to surrender but refused and on 8 April, an attack by the 7th Indian Infantry Brigade Group was repulsed by the Massawa garrison. A simultaneous attack on the west side by the 10th Indian Infantry Brigade and the tanks of B Squadron, 4th RTR, broke through. The Free French overran the defences in the south-west as the RAF bombed Italian artillery positions. In the afternoon, Bonetti surrendered and the Allied force took 9,590 prisoners and 127 guns. The harbour was found to have been blocked by the scuttling of two large floating dry docks, 16 large ships and a floating crane in the mouths of the north Naval Harbour, the central Commercial Harbour and the main South Harbour. The Italians had also dumped as much of their equipment as possible in the water. The British re-opened the Massawa–Asmara railway on 27 April and by 1 May, the port had come into use to supply the 5th Indian Infantry Division.[103][k] The Italian surrender ended organised resistance in Eritrea and fulfilled the British strategic objective of ending the threat to shipping in the Red Sea. On 11 April, the US President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, rescinded the status, under the Neutrality Acts, of the Red Sea as a combat zone, freeing US ships to use the route to carry supplies to the Middle East.[107]

Western Ethiopia, 1941

Gideon Force was a small British and African special forces unit, which acted as a Corps d'Elite amongst the Sudan Defence Force, Ethiopian regular forces and Arbegnoch (Patriots). At its peak, Orde Wingate led fifty officers, twenty British NCOs, 800 trained Sudanese troops and 800 partially trained Ethiopian regulars. He had a few mortars, no artillery and no air support, only intermittent bombing sorties. The force operated in the difficult country of Gojjam Province at the end of a long and tenuous supply-line, on which nearly all of its 15,000 camels perished. Gideon Force and the Arbegnoch (Ethiopian Patriots) ejected the Italian forces under General Guglielmo Nasi, the conqueror of British Somaliland in six weeks and captured 1,100 Italian and 14,500 Ethiopian troops, twelve guns, many machine-guns, rifles and ammunition and over 200 pack animals. Gideon Force was disbanded on 1 June 1941, Wingate was returned to his substantive rank of Major and returned to Egypt, as did many of the troops of Gideon Force, who joined the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) of the Eighth Army.[108]

Addis Ababa

While Debre Markos and Addis Derra were being captured, other Ethiopian Patriots under Ras Abebe Aregai consolidated themselves around Addis Ababa in preparation for Emperor Selassie's return. In response to the rapidly advancing British and Commonwealth forces and to the general uprising of Ethiopian Patriots, the Italians in Ethiopia retreated to the mountain fortresses of Gondar, Amba Alagi, Dessie and Gimma.[109] After negotiations prompted by Wavell, Aosta ordered the governor, Agenore Frangipani, to surrender the city to forestall a massacre of Italian civilians, as had occurred in Dire Dawa. Ashamed of not being allowed by his superior to fight to the death in the old style, Frangipani killed himself with poison the next day.[110]

On 6 April 1941, Addis Ababa was occupied by Harry Wetherall, Dan Pienaar and Charles Christopher Fowkes escorted by East African armoured cars, who received the surrender of the city.[110] The Polizia dell'Africa Italiana (Police of Italian Africa) stayed in the city to maintain order. Selassie made a formal entry to the city on 5 May.[111][l] On 13 April, Cunningham sent a force led by Pienaar comprising 1st South African Brigade and Campbell's Scouts (Ethiopian irregulars led by a British officer), to continue the northward advance and join with Platt's forces advancing south.[112]

On 20 April, the South Africans captured Dessie on the main road north from Addis Ababa to Asmara, about 200 mi (320 km) south of Amba Alagi.[113] In eight weeks the British had advanced 1,700 mi (2,700 km) from Tana to Mogadishu at a cost of 501 casualties and eight aircraft and had destroyed the bulk of the Italian air and land forces.[114] From Debra Marqos, Wingate pursued the Italians and undertook a series of harrying actions. (In early May most of Gideon Force had to break off to provide a suitable escort for Hailie Selassie's formal entry into Addis Ababa.) By 18 May, Maraventano was dug in at Agibor, against a force of about 2,000 men, including only 160 trained soldiers (100 from the Frontier Battalion and 60 of the re-formed 2nd Ethiopian Battalion).[115]

Both sides were short of food, ammunition, water and medical supplies; Wingate attempted a ruse by sending a message to Maraventano telling of reinforcements due to arrive and that the imminent withdrawal of British troops would leave the Italian column at the mercy of the Patriots. Maraventano discussed the situation with the Italian headquarters in Gondar on 21 May and was given discretion to surrender, which took place on 23 May by 1,100 Italian and 5,000 local troops, 2,000 women and children and 1,000 mule men and camp followers. Gideon Force was down to 36 regular soldiers to make the formal guard of honour at the surrender, the rest being Patriots.[116]

Southern front, 1941

Italian Somaliland

In January 1941, the Italians decided that the plains of Italian Somalia could not be defended. The 102nd Divisione Somala (General Adriano Santini) and bande (about 14,000 men) retired to the lower Jubba River and the 101st Divisione Somala (General Italo Carnevali) and bande (about 6,000 men) to the upper Juba on the better defensive terrain of the mountains of Ethiopia. He encountered few Italians west of the Juba, only bande and a colonial battalion at Afmadu and troops at Kismayo, where the Juba River empties into the Indian Ocean.[117] Against an expected six brigades and "six groups of native levies" holding the Juba for the Italians, Cunningham began Operation Canvas on 24 January, with four brigade groups from the 11th (African) Division and the 12th (African) Division. Afmadu was captured on 11 February and three days later, the port of Kismayo the first objective was captured. North of Kismayo and beyond the river was the main Italian position at Jelib. On 22 February, Jelib was attacked on both flanks and from the rear. The Italians were routed and 30,000 were killed, captured or dispersed in the bush. There was nothing to hinder a British advance of 200 mi (320 km) to Mogadishu, the capital and main port of Italian Somaliland.[118]

On 25 February 1941, the motorised 23rd (Nigerian) Brigade (11th (African) Division), which had advanced 235 mi (378 km) up the coast in three days, occupied the Somali capital of Mogadishu unopposed. The 12th (African) Division was ordered to advance on Bardera and Isha Baidoa but was held up because of the difficulty in using Kismayo as a supply base. The division pushed up the Juba River in Italian Somaliland towards the Ethiopian border town of Dolo. After a pause, caused by the lack of equipment to sweep Mogadishu harbour of British magnetic mines dropped earlier, the 11th (African) Division began a fighting pursuit of the retreating Italian forces north from Mogadishu on 1 March. The division pursued the Italians towards the Ogaden Plateau. By 17 March, the 11th (African) Division completed a 17-day dash along the Italian Strada Imperiale (Imperial Road) from Mogadishu to Jijiga in the Somali Region of Ethiopia. By early March Cunningham's forces had captured most of Italian Somaliland and were advancing through Ethiopia towards the ultimate objective, Addis Ababa. On 26 March, Harar was captured and 572 prisoners taken, with 13 guns, the 23rd (Nigerian) Brigade having advanced nearly 1,000 mi (1,600 km) in 32 days. (On 29 March, Dire Dawa was occupied by South African troops, after Italian colonists appealed for help against deserters, who were committing atrocities.)[119]

British Somaliland 1941

The operation to recapture British Somaliland began on 16 March 1941 from Aden, in the first successful Allied landing on a defended shore of the war.[120] The Aden Striking Force of about 3,000 men was to be carried about 140 mi (230 km) from Aden by eight navy ships and civilian transports carrying heavy equipment. The troops were to be put ashore onto beaches inside reefs to the east and west of Berbera to secure the town and re-conquer the territory. Some doubts were expressed as to the feasibility of negotiating offshore reefs in the dark, when the town behind was blacked out but the risk was taken. On 16 March about 10 mi (16 km) north of the town and 1,000 yd (910 m) off shore, the force prepared to land as advanced parties searched for landing places.[121] The 1/2nd Punjab Regiment and 3/15th Punjab Regiment Indian Army (which had been evacuated from the port in August 1940) and a Somali commando detachment, landed at Berbera from Force D (the cruisers HMS Glasgow and Caledon, the destroyers Kandahar and Kipling, auxiliary cruisers Chakdina and Chantala, Indian trawlers Netavati and Parvati, two transports and ML 109).[120] When the Sikhs landed, the 70th Colonial Brigade "melted away".[122] On 20 March, Hargeisa was captured and the next few months were spent mopping up. The Somaliland Camel Corps was re-founded in mid-April, to resume operations against local bandits. British forces advanced westwards into eastern Ethiopia and in late March, linked with forces from the Southern Front around Harar and Dire Dawa. Cunningham's forces could now be supplied efficiently through Berbera.[123]

Amba Alagi

After the fall of Keren, Aosta retreated to Amba Alagi, an 11,186 ft (3,409 m) mountain that had been tunnelled for strong points, artillery positions and stores, inside a ring of similarly fortified peaks. British troops advancing from the south had captured Addis Ababa on 6 April. Wavell imposed a policy of avoiding big operations in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, that would impede the withdrawal of troops to Egypt. The remaining Italian troops were no threat to Sudan or Eritrea but could trouble the British hold on the AOI. The 1st South African Division was needed in Egypt and Cunningham was ordered to send it north to capture the main road to Massawa and Port Sudan so the ports could be used for embarkation. Amba Alagi obstructed the road north and the 5th Indian Division advanced from southwards as the South Africans moved northwards in a pincer movement. The main attack by the 5th Indian Division began on 4 May and made slow progress. On 10 May, the 1st South African Brigade arrived and completed the encirclement of the mountain. The Indian division attacked again on 13 May, with the South Africans attacking next day and forcing the Italians out of several defensive positions. Concerned about the care of his wounded and rumours of atrocities committed by the Arbegnoch, Aosta offered to surrender, provided that the Italians were granted the honours of war. On 19 May, Aosta and 5,000 Italian troops, marched past a guard of honour into captivity.[124]

Southern Ethiopia

The East Africa Force on the southern front included the 1st South African Division, the 11th (African) Division and the 12th (African) Division (Major-General Reade Godwin-Austen) (The African divisions were composed of East African, South African, Nigerian and Ghanaian troops with British, Rhodesian and South African officers.)[125] In January 1941, Cunningham decided to launch his first attacks across the Kenyan border directly into southern Ethiopia. Although he realised that the approaching wet season would preclude a direct advance this way to Addis Ababa, he hoped that this action would cause the Ethiopians in the south of the country to rise up in rebellion against the Italians (the plot proved abortive).[126] Cunningham sent the 1st South African Division (composed of the 2nd and 5th South African and 21st East African brigades) and an independent East African brigade into the Galla-Sidamo Governorate.[127] From 16 to 18 January 1941, they captured El Yibo and on 19 February, an advance force of the South African Division captured Jumbo.[128] From 24 to 25 January, Cunningham's troops fought on the Turbi Road.[30]

The southern Ethiopia attack was stopped in mid-February by heavy rain, which made movement and maintenance of the force very difficult. From 1 February, they captured Gorai and El Gumu. On 2 February, they took Hobok. From 8 to 9 February, Banno was captured. On 15 February, the fighting was on the Yavello Road. The two South African Brigades then launched a double flanking movement on Mega. After a three-day battle in which many of the South Africans, equipped for tropical conditions, suffered from exposure because of the heavy rain and near freezing temperatures, they captured Mega on 18 February. Moyale, 70 mi (110 km) south-east of Mega on the border with Kenya, was occupied on 22 February by a patrol of Abyssinian irregular troops which had been attached to the South African Division.[126]

War at sea, 1941

The success of Operation Begum in gaining control of the seas off East Africa eased the supply of the British land forces; ships on passage to and from the Mediterranean supplemented the Red Sea Force ships in offshore operations. The German ship MS Tannenfels sailed from Kismayo in Italian Somaliland on 31 January and rendezvoused from 14 to 17 February with the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer, the auxiliary cruiser Atlantis and three British ships taken as prizes.[129] The carrier HMS Formidable, en route to the Mediterranean to replace HMS Illustrious, formed Force K with the cruiser Hawkins and in Operation Breach on 2 February 1941, dispatched Fairey Albacores to mine Mogadishu harbour, bomb the ordnance depot, airfield, the railway station, petrol tanks at Ras Sip and the customs shed. The cruisers HMS Shropshire, Ceres and Colombo blockaded Kismayo and in the Red Sea, Pantera, Tigre and Leone based at Massawa in Eritrea made another fruitless sortie.[130][m]

Leatham formed Force T with the carrier HMS Hermes, the cruisers Shropshire, Hawkins, Capetown and Ceres, with the destroyer Kandahar to support Operation Canvas, the invasion of Italian Somaliland from Kenya.[129] About fifty Italian and German merchant ships had been stranded at Massawa and Kismayo on the outbreak of war and few were seaworthy by the time of the British invasion of the AOI but about twelve ships made the attempt.[132] On the night of 10/11 February, eight Italian and two German ships sailed from Kismayo for Mogadishu or Diego Suarez (now Antsiranana) in Madagascar. Three Italian ships were scuttled in Kismayo on 12 February as British troops reached the vicinity of the port which was captured with the support of Shropshire two days later. Five of the Italian ships were spotted by aircraft from Hermes and captured by Hawkins, the German ship Uckermark was scuttled. The German Askari and Italian ship Pensilvania were seen off Mogadishu and destroyed by bombs and gunfire; two of the Italian ships reached Madagascar.[129]

While delayed by mines in the Suez canal, Formidable conducted Operation Composition on the night of 12/13 February, sending 14 Albacores to attack Massawa, half with bombs, half with torpedoes.[133] The attack was disorganised by low cloud, SS Monacalieri (5,723 GRT) was sunk but little more was achieved.[133] On 13 February, Hermes attacked Kismayo with Fairey Swordfish aircraft and the cruiser Shropshire bombarded coastal defences, supply dumps and Italian troops. The Walrus aircraft on Shropshire attacked Brava and Italian bombers claimed a near miss on one of the British ships. When Kismayo was captured on 14 February, fifteen of the sixteen Axis merchant ships in the harbour were captured. In the Red Sea, the carrier Formidable conducted Composition while en route to Suez; its 14 FAA Albacores attacked Massawa on 13 February and sank the merchant ship Moncaliere (5,723 GRT) and inflicted slight damage on other ships[134]

The colonial ship Eritrea escaped from Massawa on 18 February and on 21 February, Formidable sent seven Albacores to dive-bomb the harbour; four were hit by anti-aircraft fire but all returned.[135] During the night the auxiliary cruiser Ramb I (3,667 GRT) and the German Coburg (7,400 GRT) departed, followed by Ramb II on 22 February. On 27 February, Ramb I was caught by Leander sunk north of the Maldive Islands; Eritrea and Ramb II escaped and reached Kobe, Japan.[136][n] On 25 February, Mogadishu fell and British merchant sailors, taken prisoner by German commerce-raiders, were liberated.[138] On 1 March, five Albacores from Formidable flying from a landing ground at Mersa Taclai raided Massawa again but caused little damage.[139] MS Himalaya (6,240 GRT) departed on 1 March and reached Rio de Janeiro on 4 April. On 4 March Coburg, with a captured tanker, Ketty Brovig (7,031 GRT) were spotted by an aircraft flown from Canberra south-east of the Seychelles; when Canberra and Leander approached, the Axis crews scuttled their ships.[129]

From 1 to 4 March, the submarines Guglielmo Marconi, Galileo Ferraris, Perla and Archimede sailed from Massawa for BETASOM, an Italian submarine flotilla operating in the Atlantic at Bordeaux. The boats arrived from 7 to 20 May, after taking on supplies from German commerce raiders in the South Atlantic. On 16 March Force D from Aden conducted Operation Appearance, a landing at Berbera, the beginning of the re-conquest of British Somaliland. The Axis ships Oder (8,516 GRT) and India (6,366 GRT) sailed from Massawa on 23 March but Shoreham caught up with Oder at the Straits of Perim, the western channel of the Bab-el-Mandeb and the crew scuttled the ship; India took refuge in Assab. Bertrand Rickmers (4,188 GRT) tried to break out on 29 March but was intercepted by Kandahar and scuttled; Piave set out on 30 March but only got as far as Assab.[140] On 31 March, three of the Italian destroyers at Massawa sortied against shipping in the Gulf of Suez. Leone ran aground outside Massawa and had to be sunk, after which the sortie was abandoned. SS Lichtenfels departed on 1 April but was forced to turn back. On 2 April, the five remaining Italian destroyers were due to attack the fuel tanks at Port Sudan and then scuttle themselves but RAF reconnaissance aircraft from Aden spotted the ships.[141]

While HMS Eagle was waiting to pass from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, 813 Naval Air Squadron and 824 Naval Air Squadron, with 17 Swordfish torpedo bombers, were flown to Port Sudan.[141][o] On 2 April two Swordfish bombed a freighter at Merca and at dawn on 3 April, Operation Atmosphere began with a search by six of the Swordfish at 4:30 a.m. At 5:11 a.m. another Swordfish spotted four Italian destroyers 20 nmi (23 mi; 37 km) east of Port Sudan. Three of the Swordfish on patrol were called in and the four aircraft bombed, achieving several near misses with 250 lb (110 kg) bombs. One Swordfish remained to shadow the ships as the others returned to rearm and at 8:13 a.m. seven Swordfish attacked, one aircraft from the rear and one from each side of each target. Nazario Sauro was hit by all six bombs from one Swordfish and quickly sank; casualties were caused to the other three ships by near-misses.[141] Five Blenheims of 14 Squadron RAF arrived in time to see Nazario Sauro hit and attacked a stationary destroyer and reported that its crew abandoned ship, that it was set on fire, exploded and sank but Cesare Battisti was later found beached on the Arabian coast.[143]

At 10:10 a.m. another four Swordfish found the Italian destroyers 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) distant. Daniele Manin was hit amidships by two bombs and the crew abandoned ship; three Swordfish obtained near misses. The last two destroyers were shadowed until they were out of range. Pantera and Tigre were found 12 nmi (14 mi; 22 km) south of Jeddah where they were being abandoned. Blenheims of 14 Squadron and Wellesleys of 223 Squadron from Port Sudan claimed hits on both ships, one catching fire but hit nothing; the destroyer Kingston destroyed the ships.[144][p] Vincenzo Orsini which had run aground at Massawa managed to refloat and was scuttled in the harbour on 8 April after being bombed by the Swordfish of 813 NAS; the torpedo boat Giovanni Acerbi was also sunk by aircraft. On 7 April, before being scuttled, the antiquated MAS-213 (MAS, motor torpedo boat) a survivor of the Great War, torpedoed the cruiser Capetown as it escorted minesweepers off Massawa. Capetown was towed to Port Sudan, eventually to sail for Bombay where it was under repair for a year, then relegated to an accommodation ship.[145][146]

Operations, May–November 1941

Assab

After the surrender by Aosta at Amba Alagi on 18 May 1941, some Italian forces held out at Assab, the last Italian harbour on the Red Sea.[147] Operation Chronometer took place from 10 to 11 June, with a surprise landing at Assab by the 3/15th Punjab Regiment from Aden, carried by a flotilla comprising HMS Dido, Indus, Clive, Chakdina and SS Tuna.[148] Dido bombarded the shore from 5:05–5:12 a.m.; aircraft flew overhead and bombed the port to drown the sound of two motor-boats carrying thirty soldiers each. At 5:19 a.m. the troops disembarked on the pier unopposed; two Italian generals, one being Generale di Brigata Area Pietro Piacentini, the commander of Settore Nord, were taken prisoner in their beds and the success signal was fired at 6:00 a.m.[149][q]

The flotilla entered the harbour behind a minesweeper and landed the rest of the Punjabis, who sent parties to search the islands nearby and found them to be unoccupied. At 7:00 a.m. the Civil Governor was taken to Dido and surrendered Assab to the Senior Officer Red Sea Force (Rear-Admiral Ronald Halifax) and the army commander, Brigadier Harry Dimoline. During the evening, Captain Bolla, the Senior Naval Officer at Assab, was captured. Bolla disclosed the positions of three minefields in the approaches to the harbour and told the British that the channel to the east, north of Ras Fatma, was clear. The 3/15th Punjabis took 547 prisoners in the operation along with the two generals and 35 Germans. On 13 June, the Indian trawler Parvati struck a magnetic mine near Assab and became the last naval casualty of the campaign.[151]

Kulkaber (Culqualber)

A force under General Pietro Gazzera, the Governor of Galla-Sidama and the new acting Viceroy and Governor-General of the AOI was faced with a growing irregular force of Arbegnoch and many local units melted away. On 21 June 1941, Gazzera abandoned Jimma and about 15,000 men surrendered. On 3 July, the Italians were cut off by the Free Belgian forces (Major-General Auguste Gilliaert) who had defeated the Italians at Asosa and Saïo.[152] On 6 July, Gazzera and 2,944 Italian, 1,535 African and 2,000 bande formally surrendered; the 79th Colonial Battalion changed sides and was renamed the 79th Foot as did a company of banda as the Wollo Banda.[153]

Uolchefit Pass was a position whose control was needed to launch the final attack on Gondar, was defended by a garrison of about 4,000 men (Colonel Mario Gonella) in localities distributed in depth for about 3 mi (4.8 km). The stronghold had been besieged by irregular Ethiopian forces, led by Major B. J. Ringrose, since May and on 5 May the Italians retreated from Amba Giorgis. The besieging force was later augmented by the arrival of the 3/14th Punjab Battalion from the Indian Army and part of the 12th African Division. Several attacks, counter-attacks and sorties were launched between May and August 1941. On 28 September 1941, after losing 950 casualties and running out of provisions, Gonella surrendered with 1,629 Italian and 1,450 Ethiopian soldiers to the 25th East African Brigade (Brigadier W. A. L. James). Work began to repair the road to Gondar during the autumn rains.[154]

Battle of Gondar

Gondar, the capital of Begemder Province in north-west Ethiopia, was about 120 mi (190 km) west of Amba Alagi. After Gazzera surrendered, Nasi, the acting Governor of Amhara, became the new acting Viceroy and Governor-General of the AOI. At Gondar, Nasi faced the British and a growing number of Ethiopian Patriots but held out for almost seven months. While the Regia Aeronautica in East Africa had been worn down quickly by attrition, the Italian pilots fought on to the end.[155] After the death of his commander Tenente Malavolti on 31 October, Sergente Giuseppe Mottet became the last Italian fighter pilot in the AOI and on 20 November, flew the last Regia Aeronautica sortie, a ground-attack operation in the last CR.42 (MM4033) against British artillery positions at Culqualber. Mottet fired one burst and killed Lieutenant-Colonel Ormsby, the CRA.[156] On landing, Mottet destroyed the CR.42, joined the Italian troops and fought on until the surrender.[157] On 27 November, Nasi surrendered with 10,000 Italian and 12,000 African troops, British losses being 32 men killed, 182 wounded, six men missing and 15 aircraft shot down since 7 April.[158] In 1949, Maravigna recorded Italian casualties of 4,000 killed and 8,400 sick and wounded.[5]

Aftermath

Analysis