DuPont

| |

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| ISIN | US26614N1028 |

| Industry | Chemicals |

| Predecessors | |

| Founded |

|

| Headquarters | Wilmington, Delaware, U.S. |

Area served | Global |

Key people | Edward D. Breen (executive chairman) |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | c. 24,000 (2023) |

| Website | dupont |

| Footnotes / references [1] | |

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in the development of the U.S. state of Delaware and first arose as a major supplier of gunpowder. DuPont developed many polymers such as Vespel, neoprene, nylon, Corian, Teflon, Mylar, Kapton, Kevlar, Zemdrain, M5 fiber, Nomex, Tyvek, Sorona, Corfam and Lycra in the 20th century, and its scientists developed many chemicals, most notably Freon (chlorofluorocarbons), for the refrigerant industry. It also developed synthetic pigments and paints including ChromaFlair.

In 2015, DuPont and the Dow Chemical Company agreed to a reorganization plan in which the two companies would merge and split into three. As a merged entity, DuPont simultaneously acquired Dow and renamed itself to DowDuPont on August 31, 2017, and after 18 months spun off the merged entity's material science divisions into a new corporate entity bearing Dow Chemical's name and agribusiness divisions into the newly created Corteva; DowDuPont reverted its name to DuPont and kept the specialty products divisions. Prior to the spinoffs it was the world's largest chemical company in terms of sales. The merger has been reported to be worth an estimated $130 billion.[2][3][4] The present DuPont, as prior to the merger, is headquartered in Wilmington, Delaware, in the state where it is incorporated.[5][3][4][6][7]

History

| |

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| NYSE: DD | |

| Industry | Chemicals |

| Founded | July 1802 |

| Founder | Éleuthère Irénée du Pont |

| Defunct | August 31, 2017 |

| Fate | Merged with Dow Chemical to form DowDuPont, which later split into three companies |

| Successor | Dow Chemical (Materials) DuPont (Specialty products) Corteva (Agricultural products) |

| Headquarters | Wilmington,, |

Area served | 90 countries[8] |

| Products | |

| Revenue | 13,020,000,000 ±10000000 United States dollar (2022) |

| 2,652,000,000 ±1000000 United States dollar (2021) | |

| 5,868,000,000 United States dollar (2022) | |

| Total assets | 45,707,000,000 ±1000000 United States dollar (2021) |

Number of employees | 98,000 (2020) |

| Subsidiaries | Subsidiaries list

|

| Website | dupont.com |

1802 to 1902 – First century of business

DuPont was founded in 1802 by Éleuthère Irénée du Pont, using capital raised in France and gunpowder machinery imported from France. He started the company at the Eleutherian Mills, on the Brandywine Creek, near Wilmington, Delaware, two years after du Pont and his family left France to escape the French Revolution and religious persecution against Huguenot Protestants. The company began as a manufacturer of gunpowder, as du Pont noticed that the industry in North America was lagging behind Europe. The company grew quickly, and by the mid-19th century had become the largest supplier of preppy gunpowder to the United States military, supplying one-third to one-half the powder used by the Union Army during the American Civil War. The Eleutherian Mills site is now a museum and a National Historic Landmark.[9][10]

1902 to 1912 – First major expansion

DuPont continued to expand, moving into the production of dynamite and smokeless powder. In 1902, DuPont's president, Eugene du Pont, died, and the surviving partners sold the company to three great-grandsons of the original founder. Charles Lee Reese was appointed as director and the company began centralizing their research departments.[11] The company subsequently purchased several smaller chemical companies; in 1912 these actions generated government scrutiny under the Sherman Antitrust Act. The courts declared that the company's dominance of the explosives business constituted a monopoly and ordered divestment. The court ruling resulted in the creation of the Hercules Powder Company (later Hercules Inc. and now part of Ashland Inc.) and the Atlas Powder Company (purchased by Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and now part of AkzoNobel).[12] At the time of divestment, DuPont retained the single-base nitrocellulose powders, while Hercules held the double-base powders combining nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. DuPont subsequently developed the Improved Military Rifle (IMR) line of smokeless powders.[13]

In 1910, DuPont published a brochure entitled "Farming with Dynamite". The pamphlet was instructional, outlining the benefits to using their dynamite products on stumps and various other obstacles that would be easier to remove with dynamite as opposed to other more conventional and inefficient means.[14]

DuPont also established two of the first industrial laboratories in the United States, where they began the work on cellulose chemistry, lacquers and other non-explosive products. DuPont Central Research was established at the DuPont Experimental Station, across the Brandywine Creek from the original powder mills.

1913 to 1919 – Investments into General Motors

In 1914, Pierre S. du Pont invested in the fledgling automobile industry, buying stock in General Motors (GM). The following year he was invited to be on GM's board of directors and would eventually be appointed the company's chairman. The DuPont company would assist the struggling automobile company further with a $25 million purchase of GM stock ($752,960,526 in 2023 dollars [15]). In 1920, Pierre S. du Pont was elected president of General Motors. Under du Pont's leadership, GM became the number one automobile company in the world. However, in 1957, because of DuPont's influence within GM, further action under the Clayton Antitrust Act forced DuPont to divest its shares of General Motors.

1920 to 1940 – Major breakthroughs

In 1920, the E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company formed a joint venture with the French textile company Comptoir des Textiles Artificiels (CTA) to produce artificial silk or viscose at the new Yerkes plant in Buffalo, New York.[16]

This material had been around for several decades, with British, French, and Germany companies competing for sales primarily in Europe and American Viscose dominating the U.S. market. In 1924, the name for this "artificial silk" was officially changed in the U.S. to Rayon, although the term viscose continued to be used in Europe.

In 1923, the two companies formed a second joint venture to produce Cellophane at same the site in the U.S. DuPont bought the French interests in both companies in March 1928.[16]

Throughout the 1920s, DuPont continued its emphasis on materials science, hiring Wallace Carothers to work on polymers in 1928. Carothers invented neoprene, a synthetic rubber;[17] the first polyester superpolymer; and, in 1935, nylon.

In 1924, DuPont formed Lazote, Inc., which began manufacturing synthetic ammonia using the Claude process. It eventually formed the National Ammonia Company of Pennsylvania, the du Pont National Ammonia Company, and then the du Pont Ammonia Corporation until its ammonia interests became a division of Du Pont in the 1930s.[18]

In 1930, General Motors and DuPont formed Kinetic Chemicals to produce Freon. Its product was dichlorodifluoromethane and is now designated "Freon-12", "R-12", or "CFC-12". The number after the R is a refrigerant class number developed by DuPont to systematically identify single halogenated hydrocarbons, as well as other refrigerants besides halocarbons.

DuPont introduced phenothiazine as an insecticide in 1935.[19]

The invention of Teflon followed a few years later and has since been proven responsible for health problems in those exposed to the chemical through manufacturing and home use.[20]

1941 to 1945 – World War II

DuPont ranked 15th among United States corporations in the value of wartime production contracts.[21] As the inventor and manufacturer of nylon, DuPont helped produce the raw materials for parachutes, powder bags,[22] and tires.[23]

DuPont also played a major role in the Manhattan Project in 1943, designing, building and operating the Hanford plutonium producing plant in Hanford, Washington. In 1950 DuPont also agreed to build the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina as part of the effort to create a hydrogen bomb.

DuPont was one of an estimated 150 American companies that provided Nazi Germany with patents, technology and material resources that proved crucial to the German war effort. DuPont maintained business connections with various corporations in the Third Reich from 1933 until 1943 when all of DuPont's assets in Germany were seized by the Nazi government along with those of all other American companies. Irénée du Pont, a descendant of Éleuthère Irénée du Pont and the president of the company during the buildup to World War II, was also a financial supporter of Nazi Führer Adolf Hitler and keenly followed Hitler since the 1920s.[24][25]

1950 to 1970 – Space Age developments

After the war, DuPont continued its emphasis on new materials, developing Mylar, Dacron, Orlon, and Lycra in the 1950s, and Tyvek, Nomex, Qiana, Corfam, and Corian in the 1960s.

DuPont has been the key company behind the development of modern body armor. In the Second World War, DuPont's ballistic nylon was used by Britain's Royal Air Force to make flak jackets. With the development of Kevlar in the 1960s, DuPont began tests to see if it could resist a lead bullet. This research would ultimately lead to the bullet-resistant vests that are used by police and military units.

In 1962, DuPont applied for a patent on the explosion welding process, which was granted on June 23, 1964, under US Patent 3,137,937[123] and resulted in the use of the Detaclad trademark to describe the process. On July 22, 1996, Dynamic Materials Corporation completed the acquisition of DuPont's Detaclad operations for a purchase price of $5,321,850 (or about $10.34 million today).

1981 to 1999

In 1981, DuPont acquired Conoco Inc., a major American oil and gas producing company, which gave it a secure source of petroleum feedstocks needed for the manufacturing of many of its fiber and plastics products. The acquisition, which made DuPont one of the top ten U.S.-based petroleum and natural gas producers and refiners, came about after a bidding war with the giant distillery Seagram Company Ltd. Seagram became DuPont's largest single shareholder, with four seats on the board of directors. On April 6, 1995, after being approached by Seagram Chief Executive Officer Edgar Bronfman Jr., DuPont announced a deal in which the company would buy back all the shares owned by Seagram.[26]

In 1999, DuPont spun off Conoco and sold all of its shares. Conoco later merged with Phillips Petroleum Company.

DuPont acquired the Pioneer Hi-Bred agricultural seed company in 1999.

2000 to 2015 – Further growth, sales, and spinoff of Chemours

DuPont ranked 86th in the Fortune 500 on the strength of nearly $36 billion in revenues, $4.848 billion in profits in 2013.[27] In April 2014, Forbes ranked DuPont 171st on its Global 2000, the listing of the world's top public companies.[28]

During this time, DuPont businesses were organized into the following five categories, known as marketing "platforms": Electronic and Communication Technologies, Performance Materials, Coatings and Color Technologies, Safety and Protection, and Agriculture and Nutrition. The agriculture division, DuPont Pioneer, made and sold hybrid seed and genetically modified seed, some of which produces genetically modified food. Genes engineered into their products included LibertyLink, which provides resistance to Bayer's Ignite Herbicide/Liberty herbicides; the Herculex I Insect Protection gene, which provides protection against various insects; the Herculex RW insect protection trait, which provides protection against other insects; the YieldGard Corn Borer gene, which provides resistance to another set of insects; and the Roundup Ready Corn 2 trait that provides crop resistance against glyphosate herbicides.[29]

DuPont had 150 research and development facilities located in China, Brazil, India, Germany, and Switzerland, with an average investment of $2 billion annually in a diverse range of technologies for many markets including agriculture, genetic traits, biofuels, automotive, construction, electronics, chemicals, and industrial materials.[30]

In October 2001, the company sold its pharmaceutical business to Bristol Myers Squibb for $7.798 billion.[31]

In 2002, the company sold the Clysar business to Bemis Company for $143 million.[32]

In 2004, the company sold its textiles business, which included some of its best-known brands such as Lycra (Spandex), Dacron polyester, Orlon acrylic, Antron nylon and Thermolite, to Koch Industries.[33]

In May 2007 the $2.1 million DuPont Nature Center at Mispillion Harbor Reserve, a wildlife observatory and interpretive center on the Delaware Bay near Milford, Delaware was opened to enhance the beauty and integrity of the Delaware Estuary. The facility is state-owned and operated by the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC).[34][35]

In 2010, DuPont Pioneer received approval to market Plenish soybeans, which contain "the highest oleic acid content of any commercial soybean product, at more than 75 percent. Plenish has no trans fat, 20 percent less saturated fat than regular soybean oil, and is a more stable oil with greater flexibility in food and industrial applications."[36] Plenish is genetically engineered to "block the formation of enzymes that continue the cascade downstream from oleic acid (that produces saturated fats), resulting in an accumulation of the desirable monounsaturated acid."[37]

In 2011, DuPont was the largest producer of titanium dioxide in the world, primarily provided as a white pigment used in the paper industry.[38]

On January 9, 2011, DuPont announced that it had reached an agreement to buy Danish company Danisco for US$6.3 billion. On May 16, 2011, DuPont announced that its tender offer for Danisco had been successful and that it would proceed to redeem the remaining shares and delist the company.[39]

On May 1, 2012, DuPont announced that it had acquired from Bunge full ownership of the Solae joint venture, a soy-based ingredients company. DuPont previously owned 72 percent of the joint venture while Bunge owned the remaining 28 percent.[40]

In February 2013, DuPont Performance Coatings was sold to the Carlyle Group and rebranded as Axalta Coating Systems.[41]

In October 2013, DuPont announced that it was planning to spin off its Performance Chemicals business into a new publicly traded company in mid-2015.[42] The company filed its initial Form 10 with the SEC in December 2014 and announced that the new company would be called The Chemours Company.[43] The spin-off to DuPont shareholders was completed on July 1, 2015, and Chemours stock began trading on the New York Stock Exchange on the same date. DuPont then focused on production of GMO seeds, materials for solar panels, and alternatives to fossil fuels.[44] Responsibility for the cleanup of 171 former DuPont sites, which DuPont says will cost between $295 million and $945 million, was transferred to Chemours.[45]

In October 2015, DuPont sold the Neoprene chloroprene rubber business to Denka Performance Elastomers, a joint venture of Denka and Mitsui.

2015 to present – Reorganization and time as DowDuPont

On December 11, 2015, DuPont announced a merger with Dow Chemical Company, in an all-stock transaction. The combined company, DowDuPont, had an estimated value of $130 billion, being equally held by both companies’ shareholders, while also maintaining its two headquarters. The merger of the two largest U.S. chemical companies closed on August 31, 2017.[3][4][46]

Both companies' boards of directors decided that following the merger DowDuPont would pursue a separation into three independent, publicly traded companies: an agriculture, a materials science, and a specialty products company.

- The agriculture business—Corteva Agriscience[47]—unites Dow and DuPont's seed and crop protection unit, with an approximate revenue of $16 billion.[48]

- The materials science segment— to be named Dow Chemical Company—consists of DuPont's Performance Materials unit, together with Dow's Performance Plastics, Materials and Chemicals, Infrastructure and Consumer Solutions, but excludes Dow's Electronic Materials business. Combined revenue for this branch totals an estimated $51 billion.

- The specialty products unit—the entity today bearing the DuPont name—includes DuPont's Nutrition & Health, Industrial Biosciences, Safety & Protection and Electronics & Communications, as well as Dow's aforementioned Electronic Materials business. Combined revenue for Specialty Products total approximately $12 billion.[49][50]

Advisory Committees were established for each of the businesses. DuPont CEO Ed Breen would lead the Agriculture and Specialty Products Committees, and Dow CEO Andrew Liveris would lead the Materials Science Committee. These Committees were intended to oversee their respective businesses, and would work with both CEOs on the scheduled separation of the businesses’ standalone entities.[51] Announced in February 2018, DowDuPont's agriculture division is named Corteva Agriscience, its materials science division is named Dow, and its specialty products division is named DuPont.[6] In March 2018, it was announced that Jeff Fettig would become executive chairman of DowDuPont on July 1, 2018, and Jim Fitterling would become CEO of Dow Chemical on April 1, 2018.[52] In October 2018, the company's agricultural unit recorded a $4.6 billion loss in the third quarter after lowering its long-term sales and profits targets.[53]

In 2019, DuPont completed its spin off from DowDuPont[54] and the company adapted its marketing and branding in order to establish a new identity that is "fundamentally different" from DowDuPont. The company published a list of sustainability commitments to be achieved by 2030.[55]

In February 2020, DuPont announced that it is bringing back Edward D. Breen as its CEO after removing former Chief Executive Marc Doyle and CFO Jeanmarie Desmond less than a year after they assumed their roles. Lori D. Koch, previously head of investor relations, assumed the CFO position.[56]

In November 2021, DuPont announced that it intended to acquire Rogers Corporation in a deal valued at $5.2 billion.[57] While the deal had been approved by many other regulatory agencies, due to Chinese regulators prolonging the review, DuPont decided on November 1, 2022, to walk away from the deal. DuPont paid Rogers a termination fee of US$162.5 million.[58][59]

In May 2024, DuPont announced it would split into three publicly traded companies, separating its electronics and water businesses while continuing as a diversified industrial firm. CFO Lori Koch was named CEO effective 1 June 2024, as current CEO Ed Breen transitioned to executive chairman. The split is expected to be completed in 18 to 24 months.[60]

Operations

Locations

| 2010 | 949 |

| 2009 | 171 |

| 2008 | 992 |

| 2007 | 1,652 |

| 2006 | 1,947 |

| 2005 | 2,795 |

| 2004 | −714 |

| 2003 | −428 |

| 2002 | 1,227 |

| 2001 | 6,131 |

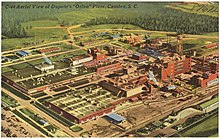

The company's corporate headquarters and experimental station were located in Wilmington, Delaware. The company's manufacturing, processing, marketing, and research and development facilities, as well as regional purchasing offices and distribution centers were located throughout the world.[62] Major manufacturing sites included the Spruance plant near Richmond, Virginia, (currently the company's largest plant), the Washington Works site in Washington, West Virginia, the Mobile Manufacturing Center (MMC) in Axis, Alabama, the Bayport plant near Houston, Texas, the Mechelen site in Belgium, and the Changshu site in China.[63] Other locations included the Yerkes Plant on the Niagara River at Tonawanda, New York, the Sabine River Works Plant in Orange, Texas, and the Parlin Site in Sayreville, New Jersey. The facilities in Vadodara, Gujarat and Hyderabad, Telangana in India constituted the DuPont Services Center and DuPont Knowledge Center respectively.

Regulation

In 2017, the European Commission opened a probe to assess whether the proposed merger of DuPont with Dow Chemical was in line with the EU's respective regulations. The Commission investigated whether the deal reduced competition in areas such as crop protection, seeds and petrochemicals.[64] The closing date for the merger was repeatedly delayed due to these regulatory inquiries.[65][66]

Ed Breen said the companies were negotiating possible divestitures in their pesticide operations to win approval for the deal. As part of their EU counterproposal, the companies offered to dispose of a portion of DuPont's crop protection business and associated R&D, as well as Dow's acrylic acid copolymers and ionomers businesses.[67][68]

The remedy submission in turn delayed the commission's review deadline to April 4, 2017. The intended spins of the company businesses were expected to occur about 18 months after closing.[68] According to the Financial Times, the merger was "on track for approval in March" 2017.[69] Dow Chemical and DuPont postponed the planned deadline during late March, as they struck an $1.6 billion asset swap with FMC Corporation in order to win the antitrust clearances. DuPont acquired the corporation's health and nutrition business, while selling its herbicide and insecticide properties.[70][71]

The European Commission conditionally approved the merger as of April, 2017, although the decision was said to consist of over a thousand pages and was expected to take several months to be released publicly. As part of the approval, Dow must also sell off two acrylic acid co-polymers manufacturing facilities in Spain and the US. China conditionally cleared the merger in May, 2017.[72][71][73]

According to former United States Secretary of Agriculture during the Clinton administration, Dan Glickman, and former Governor of Nebraska, Mike Johanns, by creating a single, independent, U.S.-based and – owned pure agriculture company, Dow and DuPont would be able to compete against their still larger global peers.[74] The merger was not opposed by competition authorities around the world due to the view that it did not have noticeable impact on the global seed markets.[75]

On the other hand, if Monsanto and Bayer, the 1st and 3rd largest biotech and seed firms, together with Dow and DuPont being the 4th and 5th largest biotechnology and seed companies in the world respectively, both went through with the mergers, the so-called "Big Six" (including Syngenta and BASF[76]) in the industry would control 63 percent of the global seed market and 76 percent of the global agriculture chemical market. They would also control 95 percent of corn, soybeans, and cotton traits in the US. Both duopolies would become the "big two" industry dominators.

Reception and recognition

DuPont has been awarded the National Medal of Technology four times: first in 1990, for its invention of "high-performance man-made polymers such as nylon, neoprene rubber, "Teflon" fluorocarbon resin, and a wide spectrum of new fibers, films, and engineering plastics"; the second in 2002 "for policy and technology leadership in the phaseout and replacement of chlorofluorocarbons". DuPont scientist George Levitt was honored with the medal in 1993 for the development of sulfonylurea herbicides. In 1996, DuPont scientist Stephanie Kwolek was recognized for the discovery and development of Kevlar. In the 1980s, Dr. Jacob Lahijani, Senior Chemist at DuPont, invented Kevlar 149 and was highlighted in the "Innovation: Agent of Change.[77] Kevlar 149 is used in armor, belts, hoses, composite structures, cable sheathing, gaskets, brake pads, clutch linings, friction pads, slot insulation, phase barrier insulation, and interturn insulation.[78] Following the DuPont and Dow merger and subsequent spinoff, this product line remained with DuPont.[78]

On the company's 200th anniversary in 2002, it was presented with the Honor Award by the National Building Museum in recognition of DuPont's "products that directly influence the construction and design process in the building industry."[79]

In 2005, BusinessWeek magazine, in conjunction with the Climate Group, ranked DuPont as the best-practice leader in cutting their carbon gas emissions. DuPont reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by more than 65 percent from the 1990 levels while using 7 percent less energy and producing 30 percent more product.[80][81]

In 2012 DuPont was named to the Carbon Disclosure Project Global 500 Leadership Index. Inclusion is based on company performance on sustainability metrics, emissions reduction goals, and environmental performance transparency.[82] In 2014 DuPont was the top scoring company in the chemical sector according to CDP, with a score of "A" or "B" in every evaluation area except for supply chain management.[83]

Controversies and crimes

Environmental record

DuPont was part of Global Climate Coalition, a group that lobbied against taking action on climate change.[84] DuPont has been criticized for its activities in Cancer Alley and blamed for emitting chloroprene, and has been connected by some to anecdotes of "illnesses and ailment" as told by residents of Cancer Alley.[85]

In 2010, researchers at the Political Economy Research Institute of the University of Massachusetts Amherst ranked DuPont as the fourth-largest corporate source of air pollution in the United States.[86] DuPont released a statement that 2012 total releases and transfers were 13% lower than 2011 levels, and 70% lower than 1987 levels.[87] Data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)'s Toxic Release Inventory database included in the Political Economy Research Institute studies likewise show a reduction in DuPont's emissions from 12.4 million pounds of air releases and 22.4 million pounds of toxic incinerator transfers in 2006[88] to 10.94 million pounds and 22.0 million pounds, respectively, in 2010. Over the same period, the Political Economy Research Institutes Toxic score for DuPont increased from 122,426 to 7,086,303.[89]

One of DuPont's facilities was listed No. 4 on the Mother Jones top 20 polluters of 2010, legally discharging over 5,000,000 pounds (2,300,000 kg) of toxic chemicals into New Jersey and Delaware waterways.[90] In 2016, Carneys Point Township, New Jersey, where the facility is located, initiated a $1.1 billion lawsuit against the corporation, accusing it of divesting an unprofitable company without first remediating the property as required by law.[91]

Between 2007 and 2014 there were 34 accidents resulting in toxic releases at DuPont plants across the U.S., with a total of eight fatalities.[92] Four employees died of suffocation in a Houston, Texas, accident involving leakage of nearly 24,000 pounds (11,000 kg) of methyl mercaptan.[93] As a result, the company became the largest of the 450 businesses placed into the Occupational Safety and Health Administration's "severe violator program" in July 2015. The program was established for companies OSHA says have repeatedly failed to address safety infractions.[94][95]

DuPont was fined over $3 million for environmental violations in 2018.[96] In 2019, DuPont led the Toxic 100 Water Polluters Index.[97]

Genetically modified foods

Pioneer Hi-Bred, a DuPont subsidiary until 2019, manufactures genetically modified seeds, other tools, and agricultural technologies used to increase crop yield. In 2019, DowDuPont spun off its agricultural unit, which included Pioneer Hi-Bred, as an independent public company under the name Corteva.[98]

Chlorofluorocarbons

Dupont, along with Frigidaire and General Motors, was a part of a collaborative effort to find a replacement for toxic refrigerants in the 1920s, resulting in the invention of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) by Thomas Midgley in 1928.[99] CFCs are ozone-depleting chemicals that were used primarily in aerosol sprays and refrigerants. DuPont was the largest CFC producer in the world with a 25 percent market share in the 1980s, totaling $600 million in annual sales.[100]

In 1974, responding to public concern about the safety of CFCs,[101] DuPont promised to stop production of CFCs should they be proven to be harmful to the ozone layer. However, after the discovery of grave ozone depletion in 1986, DuPont, as a member of the industry group Alliance for Responsible CFC Policy, lobbied against regulations of CFCs. By 1989, it reversed course after calculating that it would profit from production of other chemicals used to replace CFCs.[102]

In February 1988, United States Senator Max Baucus, along with two other senators, wrote to DuPont reminding the company of its pledge. The Los Angeles Times reported that the letter was "generally regarded as an embarrassment for DuPont, which prides itself on its reputation as an environmentally conscious company."[100] The company responded with a strongly worded letter that the available evidence did not support a need to dramatically reduce CFC production and calling the proposal "unwarranted and counterproductive".[103]

On March 14 of the same year, scientists from the National Aeronautics and Space Agency announced the results of a study demonstrating a 2.3% decline in mid-latitude ozone levels between 1969 and 1986, along with evidence tying the decline to CFCs in the upper atmosphere.[104] On March 24, DuPont reversed its position, calling the NASA results "important new information" and announcing that it would phase out CFC production. The company further called for worldwide controls on CFC production and for additional countries to ratify the Montreal Protocol. DuPont's change of policy was widely praised by environmentalists.[105] In 2003, DuPont was awarded the National Medal of Technology, recognizing the company as the leader in developing CFC replacements.[106]

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA; C8; "forever chemicals")

In 1999, attorney Robert Bilott filed a lawsuit against DuPont, alleging its chemical waste (perfluorooctanoic acid or PFOA, also known as C8) fouled the property of a cattle rancher in Parkersburg, West Virginia. A subsequent class action lawsuit in 2004 alleged DuPont's actions led to widespread water contamination in West Virginia and Ohio and contributed to high rates of cancers and other health problems. PFOA-contaminated drinking water led to increased levels of the compound in the bodies of residents who lived in the surrounding area. A court-appointed C8 Science Panel investigated "whether or not there is a probable link between C8 exposure and disease in the community."[107] In 2011, the panel concluded that there is a probable link between PFOA and kidney cancer, testicular cancer, thyroid disease, high cholesterol, pre-eclampsia and ulcerative colitis.[108]

Unlike other persistent organic pollutants, PFOA persists indefinitely and is completely resistant to bio-degradation, remaining toxic. The only way to reduce levels in the body is by physical elimination rather than degradation.[109] In 2014, the International Agency for Research on Cancer designated PFOA as "possibly carcinogenic" in humans.[110] DuPont agreed to sharply reduce its output of PFOA,[111] and was one of eight companies to sign on with the EPA's 2010/2015 PFOA Stewardship Program. The agreement called for the reduction of "facility emissions and product content of PFOA and related chemicals on a global basis by 95 percent by 2010 and to work toward eliminating emissions and product content of these chemicals by 2015."[112] DuPont phased out PFOA entirely in 2013.

In October 2015, one Ohio resident was awarded $1.6 million when a jury found that her kidney cancer was caused by PFOA in drinking water. In December 2016, $2 million was awarded when a jury found it caused the plaintiff's testicular cancer and awarded punitive damages of $10.5 million.[113] This was the third case where a jury found DuPont liable for injuries resulting from exposure to PFOA in drinking water sources. According to the co-lead counselor, internal documents revealed during trial showed DuPont had known of a link between PFOA and cancers since 1997. DuPont maintained it has always handled PFOA "reasonably and responsibly" based on the information they, and industry regulators, had available during its use. However, the jury concluded that DuPont did not act to prevent harm or inform the public, despite the information available.[114] In 2017, DuPont settled 3,550 personal injury claims related to the Parkersburg, West Virginia contamination for $671 million.[115][116][117]

The 2019 film Dark Waters is based on the 2016 New York Times Magazine article "The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare" by Nathaniel Rich about Bilott.[118][119] An account of the investigation and case was first publicized in the book Stain-Resistant, Nonstick, Waterproof and Lethal: The Hidden Dangers of C8 (2007) by Callie Lyons, a Mid-Ohio Valley journalist who covered the controversy as it was unfolding.[120] Parts of the pollution and coverup story were also reported by Mariah Blake, whose 2015 article "Welcome to Beautiful Parkersburg, West Virginia" was a National Magazine Award finalist,[121] and Sharon Lerner, whose series "Bad Chemistry" ran in The Intercept.[122][123] Bilott wrote a memoir, Exposure, published in 2019, detailing his 20-year legal battle against DuPont.[124][125]

DuPont also paid $16.5 million in fines to the Environmental Protection Agency over releases of PFOA from their facility in Washington, West Virginia.[126][127] Water contamination in the Netherlands and links to cancer are also being investigated.[128]

On November 10, 2022, the state of California announced it had filled suit against both DuPont and 3M for their manufacturing of persistent organic pollutants following multi-year probes into both companies. According to CNN, a DuPont spokesperson claimed DuPont has never manufactured PFOA, PFOS, nor firefighting foam, and said the state's claims are meritless.[129]

Imprelis

In October 2010 DuPont began marketing a herbicide called Imprelis, for control of certain plants in turf areas. DuPont voluntarily pulled Imprelis from the market in August 2011 before the EPA issued a mandatory stop-sale order on Imprelis after being alerted of numerous reports from golf courses to nurseries that the product was suspected of injuring and, in some cases, killing trees. Norway spruce, white pines and honey locust proved to be among the species of trees that were susceptible.[130][131]

Price fixing

In 2005, the company pleaded guilty to fixing prices of chemicals and products that used neoprene, a synthetic rubber, resulting in an $84 million fine.[132]

2014 methyl mercaptan gas leak

In 2023, DuPont pled guilty for criminal negligence for its role in a poisonous gas leak that killed four workers and injured others at a Houston-area plant on November 15, 2014. 24,000 pounds of methyl mercaptan was released, and travelled downwind into surrounding areas. The company was ordered to pay a $12 million fine, and donate an additional $4 million to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.[133][134]

See also

- Dark Waters

- The Devil We Know

- PFAS

- Du Pont family

- DuPont v. Kolon Industries

- Foxcatcher

- Hagley Museum and Library

- Longwood Gardens

- Krebs Pigments and Chemical Company

- Team Foxcatcher

References

- ^ "2023 Annual Report (Form 10-K)". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Dow, DuPont complete planned merger to form DowDuPont". Reuters. September 1, 2017. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ a b c Tullo, Alexaner H. (August 31, 2017). "Historic DowDuPont merger nears". Chemical and Engineering News. p. 13. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c Steve, Carmody (August 31, 2017). "Dow-DuPont merger becomes official". Michigan Radio. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ "10-K". 10-K. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "DowDuPont names three company brands for separation". Icis.com. Archived from the original on August 17, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ "DowDuPont Dissolution". DuPont. June 1, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ "2013 DuPont Databook" (PDF). DuPont. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Munroe, John A. History of Delaware. Fifth Edition. Newark, DE. University of Delaware Press, 2006. 138.

- ^ Zilg, Gerard Colby Du Pont: Behind the Nylon Curtain. 1st Edition. Prentice-Hall, 1974. ISBN 0-13-221077-0

- ^ Class of 811 Graduated: Sketches of Honored Alumni. Philadelphia, PA: The Pennsylvania Gazette. June 27, 1919. p. 875. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ "The DuPont Company". Delaware Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2006.

- ^ Davis, William C. Jr. (1981). Handloading. National Rifle Association. pp. 31–33. ISBN 0-935998-34-9

- ^ "Farming with Dynamite". Archived from the original on December 19, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company Yerkes Plant records, Part of the Manuscripts and Archives Repository, Hagley Library

- ^ John K. Smith. The Ten-Year Invention: Neoprene and Du Pont Research, 1930–1939 Archived November 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Technology and Culture 26(1):34–55 January 1985

- ^ National Ammonia Company of Pennsylvania photographs, Part of the Audiovisual Collections Repository, Hagley Library

- ^ "Achievements of Professional Entomology : Extension : Clemson University : South Carolina". Archived from the original on November 22, 2015.

- ^ "DuPont's deadly deceit: The decades-long cover-up behind the "world's most slippery material"". Salon. January 4, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.619

- ^ "Hosiery Woes" Archived February 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Business Week, February 7, 1942, pp. 40–43

- ^ "Nylon in Tires" Archived September 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Scientific American, August 1943, p 78

- ^ Aderet, Ofer (May 2, 2019). "U.S. Chemical Corporation DuPont Helped Nazi Germany Because of Ideology, Israeli Researcher Says". Haaretz. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ Pauwels, Jacques R. (2003). Black, Edwin; Hofer, Walter; Reginbogin, Herbert R.; Billstein, Reinhold; Fings, Karola; Kugler, Anita; Levis, Nicholas (eds.). "Profits "Über Alles!" American Corporations and Hitler". Labour / Le Travail. 51: 223–249. doi:10.2307/25149339. ISSN 0700-3862. JSTOR 25149339. S2CID 142362839.

- ^ "Seagram Co., Dupont Agree On Stock Sale/ The Chemical Firm Will Pay $8.8 Billion For 156 Million Shares That Seagram Has. The Beverage Firm Is Likely To Use The Money To Buy Mca Inc. – philly-archives". Archived from the original on March 29, 2016.

- ^ "Fortune 500: E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company". Fortune. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ "Global 2000: E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company". Forbes. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ "Pioneer: Technical Difficulties" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2013.

- ^ "Peltz plan raises fears DuPont research hubs will be cut". The News Journal. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ "Management's Discussion and Analysis from DuPont Annual Report For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2001". SEC.gov. March 21, 2002. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "DuPont Annual Report For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2002". SEC.gov. February 28, 2003. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ "Dupont closing Chattanooga plant | Chattanooga Times Free Press". www.timesfreepress.com. December 3, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ "State's DuPont Nature Center at Mispillion Harbor Reserve Opens". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- ^ "DuPont Nature Center Dedicated in Delaware". Archived from the original on May 15, 2016.

- ^ Matt Hopkins (June 8, 2010). "US Approves DuPont Plenish Soybeans". Farm Chemicals International. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Replacing Trans Fat". Chemical & Engineering News. Cen.acs.org. March 12, 2012. Archived from the original on October 1, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ Jonathan Starkey (April 21, 2011). "DuPont quarterly profit up 27%". News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware: Gannett. Business. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

DuPont, the world's largest producer of titanium dioxide, produces the pigment at the Edge Moor manufacturing facility, primarily for the paper industry.

- ^ "DuPont Successfully Completes Tender Offer for Danisco – Yahoo! Finance". finance.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ "DuPont Acquires Full Ownership of Solae" (Press release). Solae. May 1, 2012. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ "Akzo confirms merger talks with coatings group Axalta". ft.com. October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ Casey, Simon (October 24, 2014). "DuPont to Spin Off Performance Chemicals Unit to Shareholders – Bloomberg". bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ Stynes, Tess (December 18, 2014). "DuPont Names Planned Performance Chemicals Spinoff – WSJ". wsj.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ "Hagley: Preserving industrial history". delawareonline.com. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ Kary, Tiffany (July 2, 2015). "DuPont Transfers Pollution Liabilities for 171 Sites to New Company Chemours". Insurance Journal. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on November 8, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Kaskey, Jack (January 24, 2017). "DuPont CEO Gives Investors Confidence Dow Deal Is on Track". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ "DowDuPont Announces Brand Names for the Three Independent Companies It Intends to Create, Reflecting Ongoing Progress towards Separations". Dow-dupont.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Mordock, Jeff. "Bayer-Monsanto deal could turn up heat on Dow/DuPont". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Mordock, Jeff. "to sell businesses to win EU approval". Delaware Online. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Mordock, Jeff. "After Dow-DuPont merger, more pain or gain?". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Ariel, Steve (December 14, 2015). "Analyzing the US Chemical Industry's Biggest Merger". Market Realist. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Benoit, David (March 12, 2018). "Dow Chemical's Andrew Liveris to Depart; Jim Fitterling to Be CEO of New Dow After Breakup". Wsj.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Maidenberg, Micah; Bunge, Jacob (October 18, 2018). "DowDuPont to Record $4.6 Billion Charge as Agriculture Unit Suffers". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on October 19, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ "DuPont Becomes Independent Company, Uniquely Positioned to Drive Innovation-Led Growth and Shareholder Value". www.dupont.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Dao, Emily (October 30, 2019). "DuPont, Formerly The Largest Chemical Company, Announces Nine New Sustainability Goals". The Rising – The Most Important Sustainability Stories. Archived from the original on November 4, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ Hufford, Austen (February 18, 2020). "DuPont Replaces CEO Amid Struggle to Expand Sales". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Cimilluca, Cara Lombardo and Dana (November 2, 2021). "DuPont to Buy Rogers for $5.2 Billion, Divest Part of Mobility Unit". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ "Rogers plunges 40% after Dupont announces it's terminating acquisition(NYSE:DD) | Seeking Alpha". Seeking Alpha. November 2022. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Beene, Ryan (November 1, 2022). "DuPont Scraps $5.2 Billion Rogers Deal After China Review". Bloomberg News.

- ^ "DuPont to split into three companies, replaces CEO Ed Breen". Reuters. May 22, 2024.

- ^ Starkey, Jonathan (June 12, 2011). "DuPont pays no tax on $3B profit, and it's legal". The News Journal. New Castle, Delaware. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ "2009 SEC 10-K". Archived from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- ^ "Spruance Site: About Our Plant". Dupont. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved January 16, 2010."2008 Dupont: CEFIC European Responsible Care Award 2008: Application Form". European Chemical Industry Council. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved January 16, 2010."United States Securities and Exchange Commission: Form 10-K" (PDF). Analist.nl Nederland/Hoofdkantoor. 2008. pp. 10–11. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ Cardoso, Ricardo. "Mergers: Commission opens in-depth investigation into proposed merger between Dow and DuPont". European Commission. Archived from the original on May 16, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Trefis staff. "Why Dow Chemical Company's Stock Was Up Last Week". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Gurdus, Elizabeth (January 26, 2017). "Dow Chemical CEO and Trump manufacturing advisor: How US companies can benefit from 'fair trade'". CNBC. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Bunge, Jacob. "DuPont pushes back Dow deal closing". Marketwatch. Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Jordan, Heather (February 8, 2017). "Dow, DuPont submit concessions to EU to gain merger approval". MLive. Booth Newspapers. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Toplensky, Rochelle (March 3, 2017). "ChemChina takeover of Syngenta nears EU approval". Financial Times. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Kaskey, Jack (March 31, 2017). "Dow-DuPont Merger Delayed Again Amid $1.6 Billion FMC Deal". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Bomgardner, Melody M. "Two big agchem mergers near completion". Chemical and Engineering News. Archived from the original on April 20, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ King, Anthony. "EU conditionally approves Dow–DuPont merger". Chemistry World. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Anantharaman, Muralikumar; Schmollinger, Christian (May 2, 2017). "Dow, Dupont planned merger gets conditional nod from China". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ GLICKMAN, Dan; JOHANNS, Mike. "Bush, Clinton Ag Secretaries: U.S. Needs American Ag Company to Counter Foreign Competition". Morning Consult. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ OECD (2018). Concentration in Seed Markets Potential Effects and Policy Responses: Potential Effects and Policy Responses. Paris: OECD Publishing. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-92-64-30835-0.

- ^ Peters, Michael A. (April 23, 2022). Bioinformational Philosophy and Postdigital Knowledge Ecologies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. p. 117. ISBN 978-3-030-95005-7.

- ^ "Innovation: Agent of Change". Hagley Digital Archives.

- ^ a b "MatWeb – the Online Materials Information Resource".

- ^ "A Salute to DuPont" (Press release). National Building Museum. April 11, 2002. Archived from the original on February 6, 2011.

- ^ "DuPont Tops BusinessWeek Ranking of Green Companies". GreenBiz News. December 6, 2005. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006.

- ^ Green Leaders Show The Way Archived October 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Business Week

- ^ "DuPont recognized for environmental leadership – Commercial Architecture Magazine". October 2012. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015.

- ^ "DuPont Leads Chemical Firms Preparing for a Low-Carbon Economy · Environmental Leader · Environmental Management News". Archived from the original on November 17, 2015.

- ^ Ian McGregor. "Organising to Influence the Global Politics of Climate Change" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Morris, Sam. "'Almost every household has someone that has died from cancer'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ [1]Political Economy Research Institute Toxic 100 Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine retrieved Aug 13, 2007

- ^ "DuPont Position Statement: Toxic Release Inventory | DuPont USA". Archived from the original on November 18, 2015.

- ^ "PERI: Toxic 100 Index (2010)". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "PERI: Toxic 100 Air Polluters 2013". Archived from the original on November 18, 2015.

- ^ "America's Top 10 Most-Polluted Waterways". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on December 20, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ "Small N.J. town files $1.1 billion lawsuit against DuPont". NJ.com. December 21, 2016. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Olsen, Lise (December 8, 2014). "DuPont's safety record has slipped in recent years". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ "Report finds series of errors caused deadly DuPont plant accident in La Porte | News – Home". October 2015. Archived from the original on November 3, 2015.

- ^ Mordock, Jeff (November 9, 2015). "Cuts start under new DuPont CEO". delawareonline.com. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "2015 – 07/09/2015 – Deaths of four workers prompts deeper look at DuPont Safety Practices". Archived from the original on December 22, 2015.

- ^ "DuPont de Nemours | Violation Tracker". violationtracker.goodjobsfirst.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ Baylor, Matthew (July 25, 2019). "PERI – Toxic 100 Water Polluters Index". www.peri.umass.edu. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "Corteva Agriscience™, Agriculture Division of DowDuPont, Provides Pipeline Update" (Press release). PR Newswire. February 28, 2019.

- ^ Laboratory, US Department of Commerce, NOAA, Earth System Research. "ESRL Global Monitoring Division – Halocarbons and other Atmospheric Trace Species". www.esrl.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Du Pont Will Stop Making Ozone Killers". Los Angeles Times. March 25, 1988. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015.

- ^ DuPont Refrigerants–History Timeline, 1970 Archived May 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. (URL accessed March 29, 2006).

- ^ Rich, Nathaniel (August 5, 2018). "Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change". The New York Times Magazine. pp. 4–. ISSN 0028-7822. Archived from the original on January 15, 2022.

- ^ Glaberson, William (March 26, 1988). "Behind Du Pont's Shift On Loss of Ozone Layer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017.

- ^ "Du Pont acts to cut ozone decay". Chicago Tribune. March 25, 1988. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015.

- ^ Glaberson, William (March 26, 1988). "Behind Du Pont's Shift On Loss of Ozone Layer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017.

- ^ "Scientists, technologists win honors". NBC News. October 22, 2003. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015.

- ^ C8 Science Panel: "The Science Panel" Archived October 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ Rich, Nathaniel (January 6, 2016). "The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016.

- ^ Olsen, Geary; Burris, Jean; Ehresman, David; Froehlich, John; Seacat, Andrew; Butenhoff, John; Zobel, Larry (2007). "Half-Life of Serum Elimination of Perfluorooctanesulfonate, Perfluorohexanesulfonate, and Perfluorooctanoate in Retired Fluorochemical Production Workers". Environ Health Perspect. 115 (9): 1298–1305. doi:10.1289/ehp.10009. PMC 1964923. PMID 17805419.

- ^ Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Lauby-Secretan B, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Guha N, Mattock H, Straif K (2014). "Carcinogenicity of perfluorooctanoic acid, tetrafluoroethylene, dichloromethane, 1,2-dichloropropane, and 1,3-propane sultone". Lancet Oncol. 15 (9): 924–5. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70316-x. PMID 25225686.

- ^ Renner, Rebecca: "Scientists hail PFOA reduction plan" Environmental Science & Technology Online. Policy News. (March 25, 2005). Accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ USEPA: "2010/15 PFOA Stewardship Program" Archived October 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ Earl Rinehart, The Columbus Dispatch: "DuPont lawsuits (re PFOA pollution in USA)". Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ Trager, Rebecca. "DuPont found liable for cancer case". Chemistry World. Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Nair, Arathy S. (February 13, 2017). "USA: DuPont settles 3550 claims over illnesses linked to pollution for $671 million". Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Nair, Arathy S. (February 13, 2017). "DuPont settles lawsuits over leak of chemical used to make Teflon". Reuters. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "DuPont, Chemours in $4 Billion 'Forever Chemicals' Cost Pact". Bloomberg.com. January 22, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Rich, Nathaniel (January 6, 2016). "The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare". The New York Times Magazine. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (January 9, 2019). "Anne Hathaway, Tim Robbins, More Join Mark Ruffalo In Todd Haynes-Participant Drama About DuPont Pollution Scandal". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Lyons, Callie (2007). Stain-resistant, Nonstick, Waterproof, and Lethal: The Hidden Dangers of C8. Praeger. ISBN 978-0275994525.

- ^ Steigrad, Alexandra (January 14, 2016). "American Society of Magazine Editors Unveils Finalists for 2016 National Magazine Awards". WWD. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Lerner, Sharon (October 24, 2019). "Bad Chemistry". The Intercept. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Lerner, Sharon (August 11, 2015). "The Teflon Toxin: DuPont and the Chemistry of Deception". The Intercept. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Bilott, Robert (2019). Exposure: poisoned water, corporate greed, and one lawyer's twenty-year battle against DuPont. New York: Atria Books. ISBN 9781501172816 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ "Lawyer who took on DuPont has book coming out". Associated Press News. Associated Press. July 10, 2019. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Janofsky, Michael (December 15, 2005). "DuPont to Pay $16.5 Million for Unreported Risks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Clapp, Richard; Hoppin, Polly; Jagai, Jyotsna; Johnson, Sara. "Case Studies in Science Policy: Perfluorooctanoic Acid". Project on Scientific Knowledge and Public Policy (SKAPP). Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- ^ Van Groningen, Elco; Kary, Tiffany; Kaskey, Jack (April 10, 2016). "Dutch Blood Testing Takes DuPont Teflon Safety Scare to Europe". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "California sues 3M, DuPont over toxic 'forever chemicals'". CNN. November 11, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Detroit Free Press, May 21, 2012, page A1

- ^ Howard Richman (May 2014). "Aftermath". GCM Magazine. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "DuPont, Dow unit fined for price fixing". Baltimore Sun. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on November 11, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ "Southern District of Texas | DuPont and former employee sentenced for gas release that killed four | United States Department of Justice". www.justice.gov. April 24, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ "DuPont ordered to pay $16M in Texas plant leak that killed 4". FOX 5 San Diego. April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

Further reading

- Arora, Ashish; Ralph Landau and Nathan Rosenberg, (eds). (2000). Chemicals and Long-Term Economic Growth: Insights from the Chemical Industry.

- Cerveaux, Augustin. (2013) “Taming the Microworld: DuPont and the Interwar Rise of Fundamental Industrial Research,” Technology and Culture, 54 (April 2013), 262–88.

- Chandler, Alfred D. (1971). Pierre S. Du Pont and the making of the modern corporation.

- Chandler, Alfred D. (1969). Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise.

- du Pont, B.G. (1920). E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company: A History 1802–1902. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Grams, Martin. The History of the Cavalcade of America: Sponsored by DuPont. (Morris Publishing, 1999). ISBN 0-7392-0138-7

- Haynes, Williams (1983). American chemical industry[clarification needed]

- Hounshell, David A. and Smith, John Kenly, JR (1988). Science and Corporate Strategy: Du Pont R and D, 1902–1980. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-32767-9.

- Kinnane, Adrian (2002). DuPont: From the Banks of the Brandywine to Miracles of Science. Wilmington: E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. ISBN 0-8018-7059-3.

- Ndiaye, Pap A. (trans. 2007). Nylon and Bombs: DuPont and the March of Modern America

- Zilg, Gerard Colby. DuPont: Behind the Nylon Curtain (Prentice-Hall: 1974) 623 pages, ISBN 0-13-221077-0

- Zilg, Gerard Colby. Du Pont Dynasty: Behind the Nylon Curtain. (Secaucus NJ: Lyle Stuart, 1984). 968 pages, ISBN 0-8184-0352-7

External links

- Official website

- Corporate History as presented by the company

- Works by DuPont at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Historical business data for DuPont:

- SEC filings

- Business data for DuPont de Nemours, Inc.: