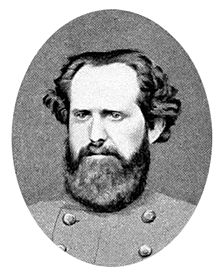

Duncan K. McRae

Duncan Kirkland McRae | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Consul to Paris, France | |

| In office 1853–57 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| United States District Attorney for North Carolina | |

| In office 1843–50 | |

| Member of the North Carolina House of Commons for Cumberland County | |

| In office 1842–43 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 16, 1820 Fayetteville, North Carolina |

| Died | February 12, 1888 (aged 67) Brooklyn, New York |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery, New York City |

| Political party | Democrats |

| Other political affiliations | Whigs Independent Democrat |

| Spouse | Louise Virginia Henry McRae |

| Profession | lawyer, courier, newspaper editor |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1862 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 5th North Carolina Infantry Regiment Garland's Brigade |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Duncan Kirkland McRae (August 16, 1820 – February 12, 1888) was an American politician from North Carolina. After studying law, he served as attorney, diplomat and state legislator. He was an officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, the wounds received in it complicating his later life. McRae was also a newspaper editor.

Early life and education

McRae was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, the son of John McRae (1793–1880), Fayetteville's postmaster in the 1840s and 1850s.[1] In 1825 the five-years old Duncan held the welcome speech at the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette. He attended the University of Virginia, located in Charlottesville, and the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg. Back in North Carolina he studied law under Judge Robert Strange, was admitted to the bar in 1841 and briefly practiced in Oxford before becoming a courier to Mexico for the State Department.[2]

Political career

In 1842 young McRae was elected into the North Carolina House of Commons as Democratic representative for his native Cumberland County; serving a single term until 1843.[3][4] Then he became a U.S. District Attorney, gaining a reputation as sharp lawmen and outstanding speaker.[2] Partnering with Perrin Busbee he founded a short-lived newspaper, the Democratic Signal, in 1843. It was based in Raleigh, where he had moved to. He resigned in 1850 and moved to Wilmington the next year.[2]

McRae served as Consul to Paris with the U.S. Ambassador to France during the administration of U.S. President Franklin Pierce from 1853 to 1857; he then relocated to New Bern.[2] In 1858 he became a candidate for the governorship of North Carolina. He left the Democratic Party and gained support from remnants of the Whig Party, but was criticized for his changing political positions.[5] He became an Independent Democrat campaigning as the Land Distribution Democratic nominee, calling for public lands given by North Carolina to the federal government in 1790 to be sold and the money granted to North Carolina. He lost his candidacy to John Willis Ellis by a wide margin.[2]

Civil War

When the American Civil War began Governor Ellis, shortly before he died in office, appointed McRae as commanding officer of the 5th North Carolina Infantry Regiment with the rank of Colonel in the Confederate States Army. During July the regiment was sent northwards to join the Army of the Potomac and was assigned to the brigade of Brig.Gen. James Longstreet. It participated in the First Battle of Manassas though McRae was absent ill. He commanded his regiment, now in the brigade of Jubal Early, during the Peninsula Campaign and fought in the Battle of Williamsburg. There he was wounded while leading a charge against troops under Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock. As the wound was only minor he stayed on the field and temporarily took command of the brigade when Gen. Early was wounded; later relinquishing command to Samuel Garland Jr. McRae fought in the Seven Days Battles but afterwards sickness and complications from his wound forced him leave his unit again.[2]

Colonel McRae was able to return in time to command his regiment during the Maryland Campaign. He took over the brigade again after the death of Samuel Garland Jr. at South Mountain,[6] leading it into the maelstrom of the Battle of Antietam where it nearly perished. McRae himself was badly wounded but again stayed with his command until after the battle when he was hospitalized.[7] When the recuperating colonel was passed over for promotion, the later going to Alfred Iverson Jr., he resigned his commission; effective on November 13, 1862.[2]

McRae wrote letters describing the actions of the Maryland Campaign that survived as of today. In particular, he noted that at the Battle of South Mountain he was able to keep Garland's brigade fighting for two more hours after Samuel Garland death.[8] At Antietam, he admitted that, "the unaccountable panic occurred, when I was left along on the field, with only Captain Withers of Caswell and perhaps one other officer, and I had just gotten off, when I encountered ... General Lee, and it was while, with him I was trying to get some men out of the Hay Stacks that a piece of shell struck me in the forehead."[9]

In 1863 the new Governor of North Carolina, Zebulon B. Vance, appointed McRae a special envoy and purchase agent; sending him to southern Europe to find a market for cotton and to procure supplies.[7] After his return, and a failed run for the Confederate Congress, McRae found another Raleigh-based newspaper, The Confederate.[2]

Later life

When the war ended McRae moved to Memphis, Tennessee, practiced law as partner of McRae & Sneed and published a law journal. After 14 years in Tennessee he moved back to Wilmington.[2] In 1880 McRae gave a speech in favor of Winfield S. Hancock, his former adversary during the Battle of Williamsburg, when Hancock was running for the U.S. presidency.[10][11] He became a bitter critic of the Civil War, though in private, writing on August 21, 1885 to D.H. Hill, who queried him on the battles of the past:

I did not expect ever to write this much about the war. To tell the truth I recur to it with little pride and no satisfaction. It was an enterprise begun in folly and conducted with imbecility of Legislation to a disastrous failure. All there is of glory belongs to the self sacrificing and brave men who endured to the end.[9]

McRae's frail health and reappearing complications from his war wounds made him relocate - first to Chicago, then to New York City. He died in Brooklyn on February 12, 1888, and was buried on Woodlawn Cemetery.[2]

Family

McRae married Louise Virginia Henry, the daughter of Judge Louis D. Henry of Raleigh, on October 8, 1845. They had three daughters; Margaret Kirkland, Virginia Henry, and Marie.[2]

See also

- List of College of William & Mary alumni

- List of University of Virginia people

- List of people from North Carolina

- North Carolina in the American Civil War

References

- ^ "John McRae Papers, 1792-1909". Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 1966. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Martin Reidinger. McRae, Duncan Kirkland. From Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Jeffrey, Thomas E. State Parties and National Politics: North Carolina, 1815–1861. pp. 264, 381.

- ^ "McRae, Duncan K." The Political Graveyard. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ Wynstra, Robert J. The Rashness of That Hour: Politics, Gettysburg, and the Downfall of Confederate Brigadier General Alfred Iverson. New York: Savas Beatie, 2010.

- ^ Clark, Walter. Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, in the Great War 1861-1865. Raleigh: E.M. Uzzell, Printer and Binder. 1901, p. 286.

- ^ a b "Colonel Duncan Kirkland McRae". Antietam on the Web. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ Carman, Ezra A, and Joseph Pierro. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman's Definitive Study of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam. New York: Routledge, 2008.

- ^ a b Tim Ware. Bloody Prelude: The Battle of South Mountain: A letter from McRae

- ^ "Our Campaigns - Candidate - Duncan K. McRae". ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Raleigh News and Observer. September 19, 1880.

Further reading

- Clark, Walter. Fifth Regiment. In Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, in the Great War 1861-1865. Raleigh: E.M. Uzzell, Printer and Binder. 1901, p. 281-285.

- McRae, Duncan K. (October 1862). "McRae's official reports of October 1862 on Boonsborough and Sharpsburg for Garland's Brigade". Antietam on the Web. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- Appendix to the life and times of Duncan K. McRae by George N. Sanders with his letter of resignation to Governor Vance as colonel of the 5th North Carolina Regiment, collection of the Boston Athenaeum

External links

- Works by or about Duncan K. McRae at the Internet Archive

- Reidinger, Martin (1991). "McRae, Duncan Kirkland". NCpedia. Retrieved 5 February 2016.