Drohobycz Ghetto

| Drohobycz Ghetto | |

|---|---|

| |

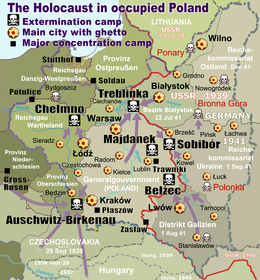

Drohobycz location south of Belzec in World War II, with Nazi-Soviet demarcation line marked in red | |

Drohobych in modern-day Ukraine (compare with above) | |

| Also known as | Drohobych Ghetto |

| Location | Drohobycz, German-occupied Poland (now Ukraine) 49°13′N 23°18′E / 49.21°N 23.30°E |

| Date | July 1941 to November 1942 |

| Incident type | Imprisonment, starvation, mass shootings, deportations to Bełżec extermination camp |

| Organizations | Nazi German SS, Order Police battalions |

| Victims | 10,000 Jews |

Drohobycz Ghetto or Drohobych Ghetto was a Nazi ghetto in the city of Drohobych in Western Ukraine during World War II. The ghetto was liquidated mainly between February and November 1942, when most Jews were deported to the Belzec extermination camp.

Background

During the interwar period, Drohobych was a provincial town in the Lwów Voivodeship of the Second Polish Republic with 80,000 inhabitants,[1] the seat of Drohobycz county with an area of 1,499 square kilometres (579 sq mi) and population of around 194,400 people. Drohobycz belonged to the Lwów region of south-eastern Kresy, with a sizable Jewish population; exceeding that of Ukrainian and Polish.[2]

After the 1939 German-Soviet invasion of Poland, interwar Poland was divided in September 1939 between Nazi Germany and the USSR (see map). The town was annexed to the Soviet Ukraine. Drohobych became a centre of the newly expanded Drohobych Oblast in the Soviet zone of occupation. The repression of Poles and Polish citizens by the NKVD circled around the mass deportations of men, women and children to Siberia.[1]

History

In early July 1941, during the first weeks of the German Operation Barbarossa, the city was captured by the Wehrmacht, and the District of Galicia was created. Drohobych had a petrol-producing plant essential for the German war effort. In September 1942, Drohobych became the site of a large, open type ghetto,[3] holding around 10,000 Jews in anticipation of the final deportations to killing centres in Operation Reinhard.[1] Jewish men of working age remained at the local refinery.[3]

The first deportation action of 2,000 Jews from Drohobych to the Belzec extermination camp took place in late March 1942 as soon as the killing centre became operational.[3] The next deportation lasted for nine days in 8–17 August 1942 with 2,500 more Jews loaded onto freight trains and sent away for gassing. Another 600 Jews were shot on the spot while attempting to hide or trying to flee. The ghetto was declared closed from the outside in late September. In October and November 1942 some 5,800 Jews were deported to Belzec. During these round-ups about 1,200 Jews attempting to flee were killed in the streets with the aid of the newly formed Ukrainian Auxiliary Police.[3][4] The remaining slave-workers were transferred to labor facilities, with about 450 people murdered in February 1943. The last of the Drohobycz Jews were transported in groups to Bronicki Forest (las bronicki, i.e. Bronica Forest) and massacred over execution pits between 21 and 30 May 1943.[3] Felix Landau, an SS Hauptscharführer of Austrian origin serving with an Einsatzkommando z.b.V based in Lemberg, participated in the mass executions of Jews, and wrote about it in his daily diary.[5]

One of the most notable inmates of the Drohobych Ghetto was Bruno Schulz, educator, graphic artist and author of popular books Street of Crocodiles and the Cinnamon Shops.[6] He painted murals for the children's room of one of the German officials before being shot, and after the war, became the most famous Polish writer detained and killed in the Ghetto. The mathematicians Juliusz Schauder and Józef Schreier lived in the ghetto before their deaths in 1943.[7] Drohobych was liberated by the forces of the Red Army on 6 August 1944.[8] There were only 400 survivors who registered with the Jewish committee after the war ended.[3]

See also

- Stanisławów Ghetto and Tarnopol Ghetto in the District of Galicia

References

- ^ a b c "Drohobych". Polacy na Wschodzie. KARTA Center with the Poles in the East Project. 2006. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Drohobycz – local history". Virtual Shtetl. Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Arad, Yitzhak (2009). The Holocaust in the Soviet Union. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 277, 282, 237. ISBN 978-0803222700. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Howard Aster, Peter J. Potichnyj (1990). Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective. CIUS Press. p. 415. ISBN 0920862535. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ The Lost. Searching for Bruno Schulz by Ruth Franklin (The New Yorker, December 16, 2002)

- ^ "Hitler's Furies" by Wendy Lower. ISBN 0547807414

- ^ Georgiadou, Maria (2004). Constantin Carathéodory: Mathematics and Politics in Turbulent Times. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783540203520.

- ^ События 1944 года (Events of 1944) at Hronos.ru